It wasn’t long ago that scientists had given up on finding life in the Solar System. Venus and Mercury are too hot, Mars too dry, and everything else way too cold. But thanks to a series of space probes a couple of decades ago, that dismal verdict has been dramatically reversed. Several of the ice-covered moons of Saturn and Jupiter, it turns out, conceal subsurface seas of liquid water, an essential ingredient for life as we know it.

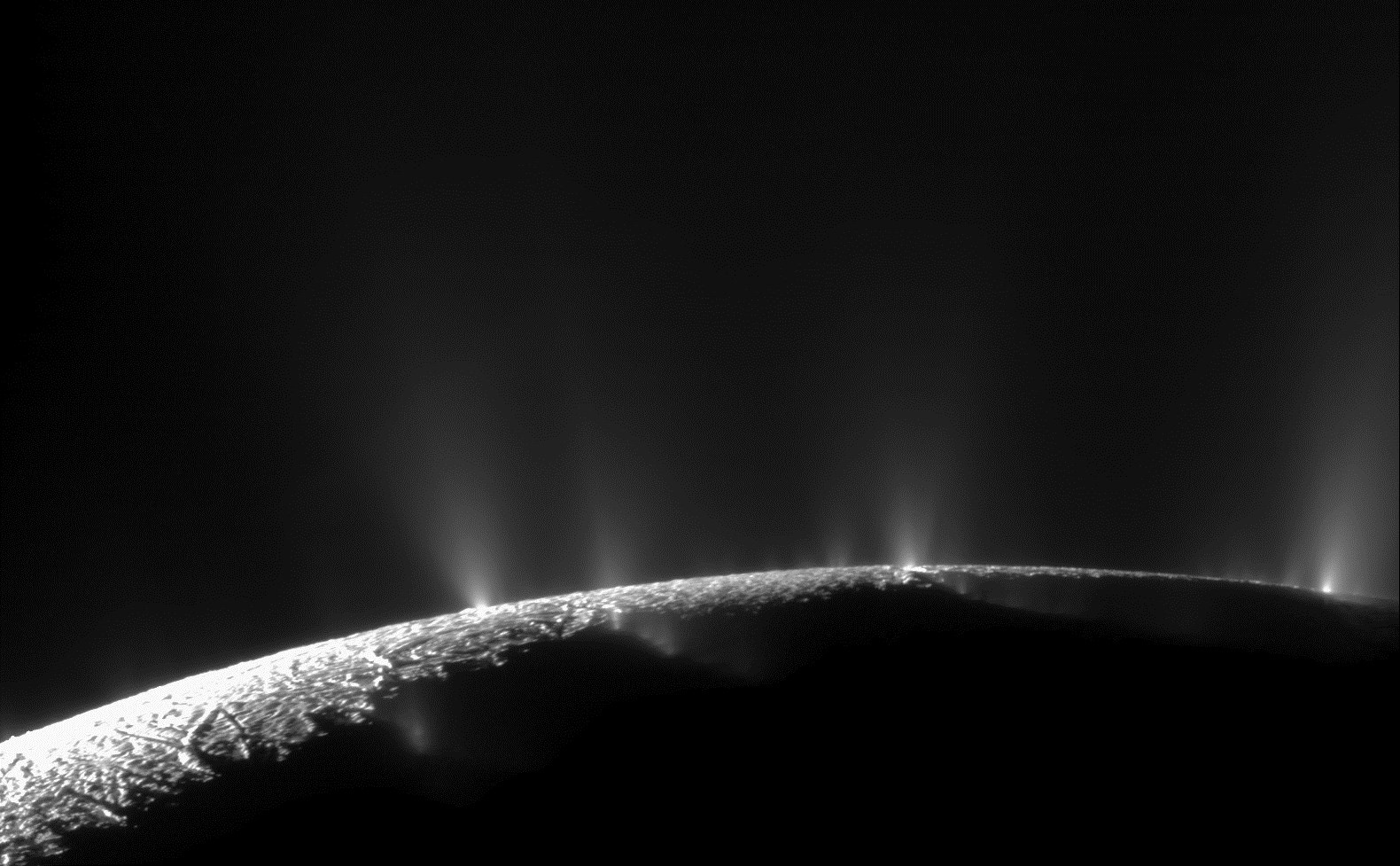

That doesn’t mean life is necessarily out there—but if it is, new images coming down from NASA’s Cassini space probe, described in two papers just published in the Astronomical Journal are making a powerful argument that Saturn’s moon Enceladus may be the best place to look. The latest evidence: images that show no fewer than 101 geysers of water erupting from cracks in the moon’s southern hemisphere. “I’m really excited,” says Carolyn Porco, head of the spacecraft’s imaging team.

Who can blame her? The fact that Enceladus spews water into space is no surprise: Cassini spotted plumes of the stuff rising from the moon’s icy surface as soon as it took the first close-up images when the craft arrived back in 2004. There’s so much material escaping from Enceladus, in fact, that gives substance to one of the planet’s majestic rings.

The question was: Were the plumes coming from just below the surface, or from deep inside the moon? Only the latter would be good news for life, since it would imply a reservoir of permanently liquid water where life could have arisen and gained a foothold. That hope was strongly bolstered when Cassini’s flew through a plume in 2009. It’s instruments “tasted” the water and found it salty—strong evidence that the H2O had come from deep enough that it had been in prolonged contact with minerals in Enceladus’ rocky core.

Even more evidence came along just a few months ago: by measuring subtle variations in the moon’s gravity field, Cassini showed that an ocean really does lie about 30 miles under Enceladus’s thick rind of ice, bearing enough water to fill Lake Superior.

It all fit together—and the latest images just make the case stronger. It was still possible, says Porco, that the plumes of water coming from Europa originated mostly in the top few yards of the moon’s surface, created by tidal flexing whose friction was melting the ice. If that were the case, though, the geysers should be shooting out of a relatively wide area.

But they’re not. Instead, says Porco, “we found that they’re coming from four prominent fractures in the south polar terrain.” The fractures are known informally as “tiger stripes,” and in the case of three or four of the geysers, the locations have been pinpointed as coming from hotspots just a few tens of yards across.

“That’s the big thing here,” she says. “These are clearly not a near-surface phenomenon. This tells us that the only plausible source geysers is the sea below. We’re confident now that the fractures go all the way down.”That being the case, any biological activity in the ocean might be detectable in water from the plumes—if Cassini had the right instruments to detect it. It doesn’t, and that, says Porco, “makes it imperative to mount a mission to go back.”

It’s not that Enceladus is more likely to have life than, say, Jupiter’s moon Europa, which also boasts a liquid ocean beneath a crust of ice, says Porco. But the plumes on Enceladus offer a direct window into the ocean below. “You go back, land, stick out your tongue, and you get what you paid for,” she says. “We could go to town.”

Even at a time when NASA is badly hurting for cash, that could be a tough argument to resist.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com