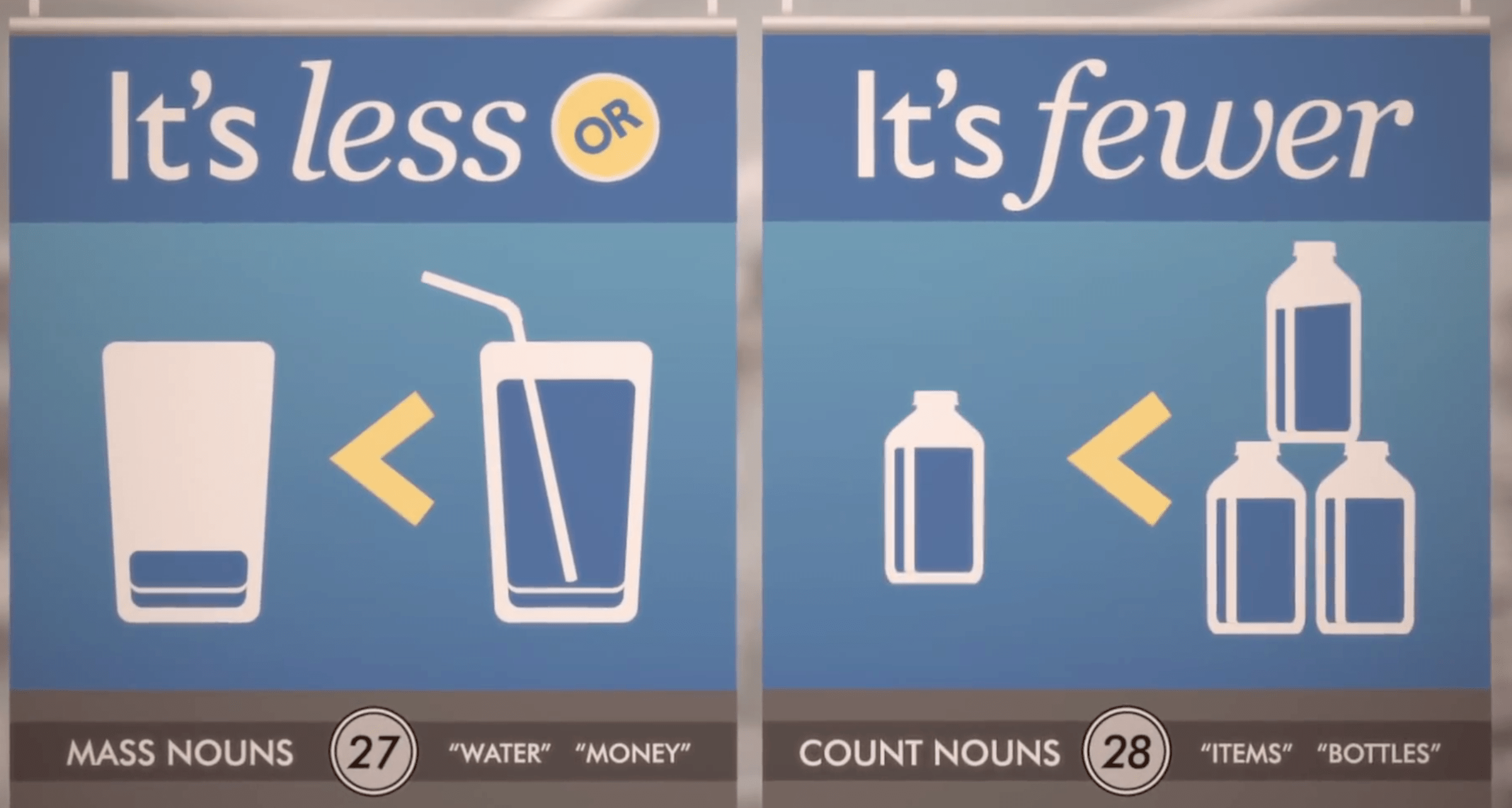

The plaque commemorating pitcher Greg Maddux’s induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame this week testifies that he is the “only hurler with 300 wins, 3,000 strikeouts and less than 1,000 walks.” If you winced, or for that matter hurled, at the use of less instead of fewer, you may be a careful reader, a grammar snob — or Weird Al Yankovic.

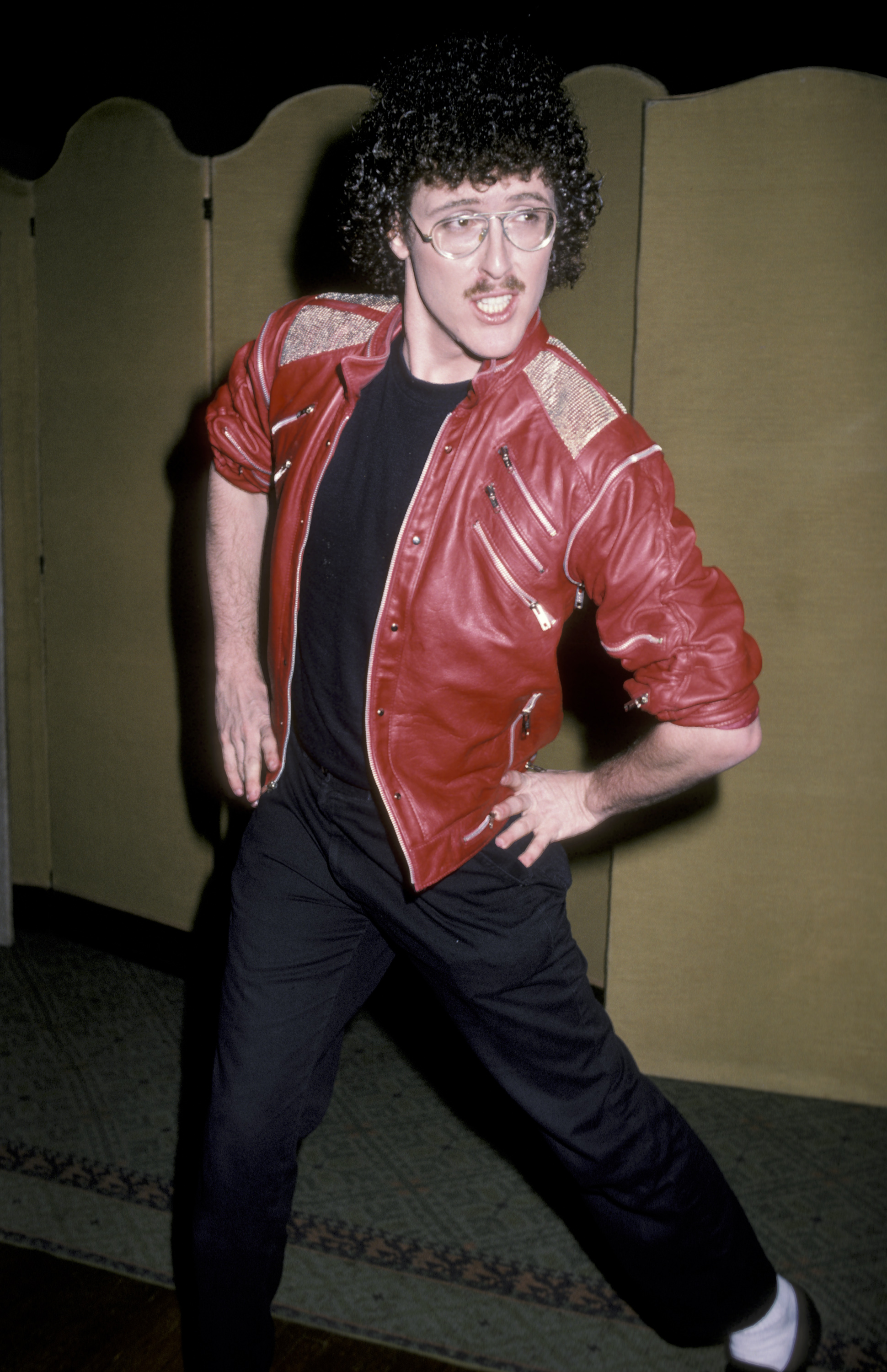

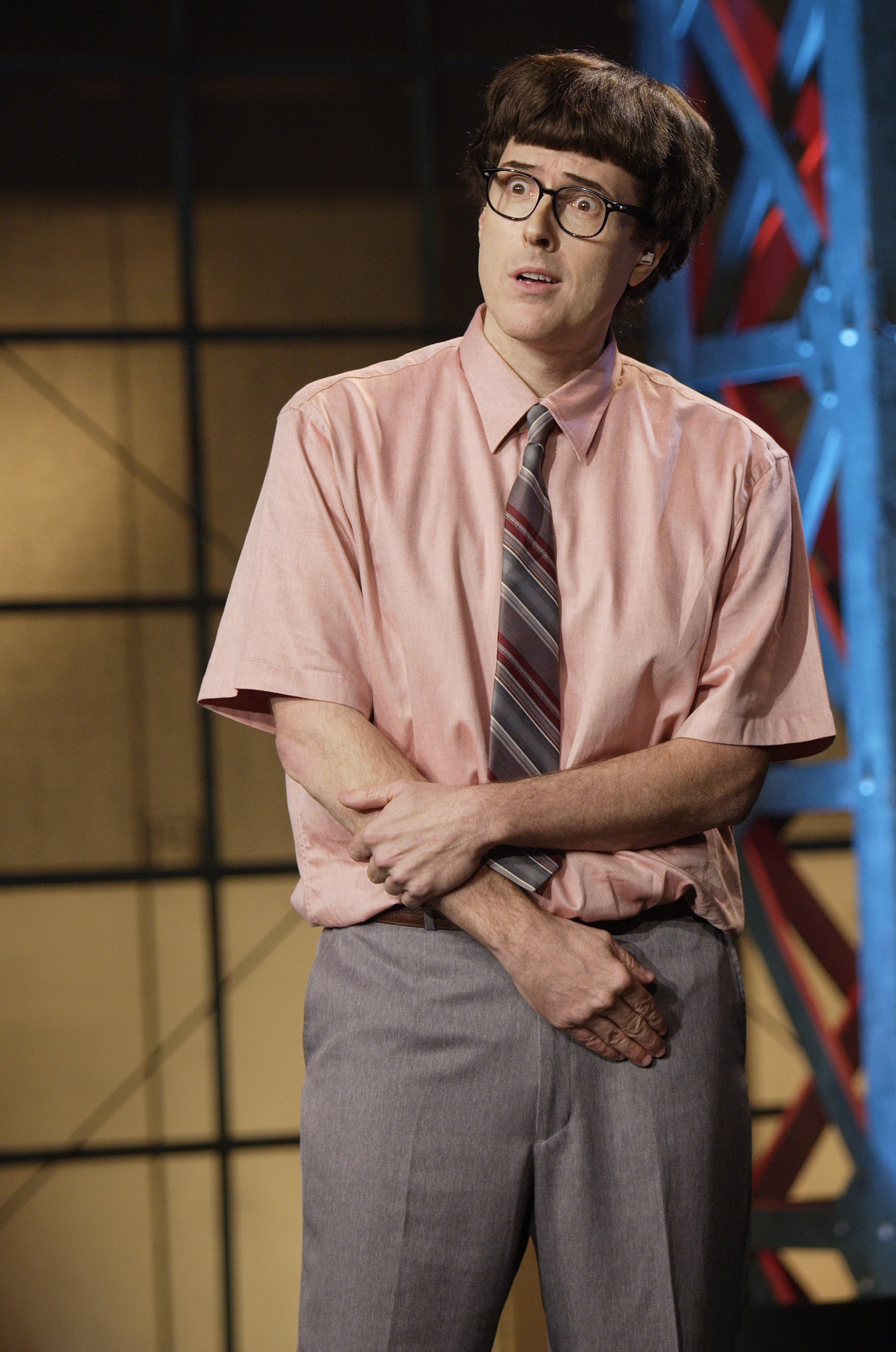

At 56, after nearly 40 years of musical burlesques, the accordion-grinding pop satirist has scored his first top-of-the-pops CD with the album Mandatory Fun. It’s (not its) the first comedy album to reach No. 1 since 1963, when Allan Sherman’s My Son, the Nut reigned on the Billboard charts, propelled by its (not it’s) hit single “Hello Muddah, Hello Faddah” (insert commas). The Yankovic number that has attracted more than (not over) 12 million listens on YouTube — and which (not that) everyone is sending to his or her (never their) friends — is “Word Crimes,” a “Blurred Lines” parody that (not which) itemizes crimes against the language. English teachers, on realizing that Weird Al has become the arbiter for proper grammar, may figuratively (not literally) look for the nearest bridge to jump off. And yes, it’s O.K. to end a sentence with a preposition, and to use the word O.K.

(WATCH: Weird Al Yankovic’s “Word Crimes” video)

Aside from dry-cleaning the smut from last summer’s Robin Thicke–Pharrell Williams smash, “Word Crimes” serves as an instant anthem for any language maven (Hebrew for expert) or alter kocker (senior citizen, from the Yiddish for old poop) who has mourned the slippage of good grammar over the years, especially with the rise of social media. (And aren’t all media social?). In 1990, if you had told Weird Al that young people would soon be communicating as much by writing as by telephoning, he might have dared hope that the return of literacy would wipe out a generation of slang mumblings: “I mean, like, you know?” Texting has reduced the number of waste words, but it has also exposed a black hole of ignorance about traditional — what a cranky guy would call correct — grammar.

Or maybe the texters could care less, which for Yankovic is another word crime: “That means you do care/ At least a little.” The texters might explain gently to Al, as to a grandparent from the old country, that “I could care less” is an example of irony; and Al would snap back, “Irony is not coincidence.” The exact meaning of irony is so narrow that the word is hardly worth using; in its broad, current definition, it’s a euphemism for sarcasm. “I’m not being sarcastic; I’m being ironic.” No, you’re not. You’re evading the responsibility for being sarcastic. You’re also being a sloppy thinker — just as someone using literally (in Yankovic’s example “You ‘literally couldn’t get out of bed'”) almost always means figuratively, and a sentence beginning “With all due respect” almost always presages an insult.

(READ: Lily Rothman on the no-longer-so-weird Al)

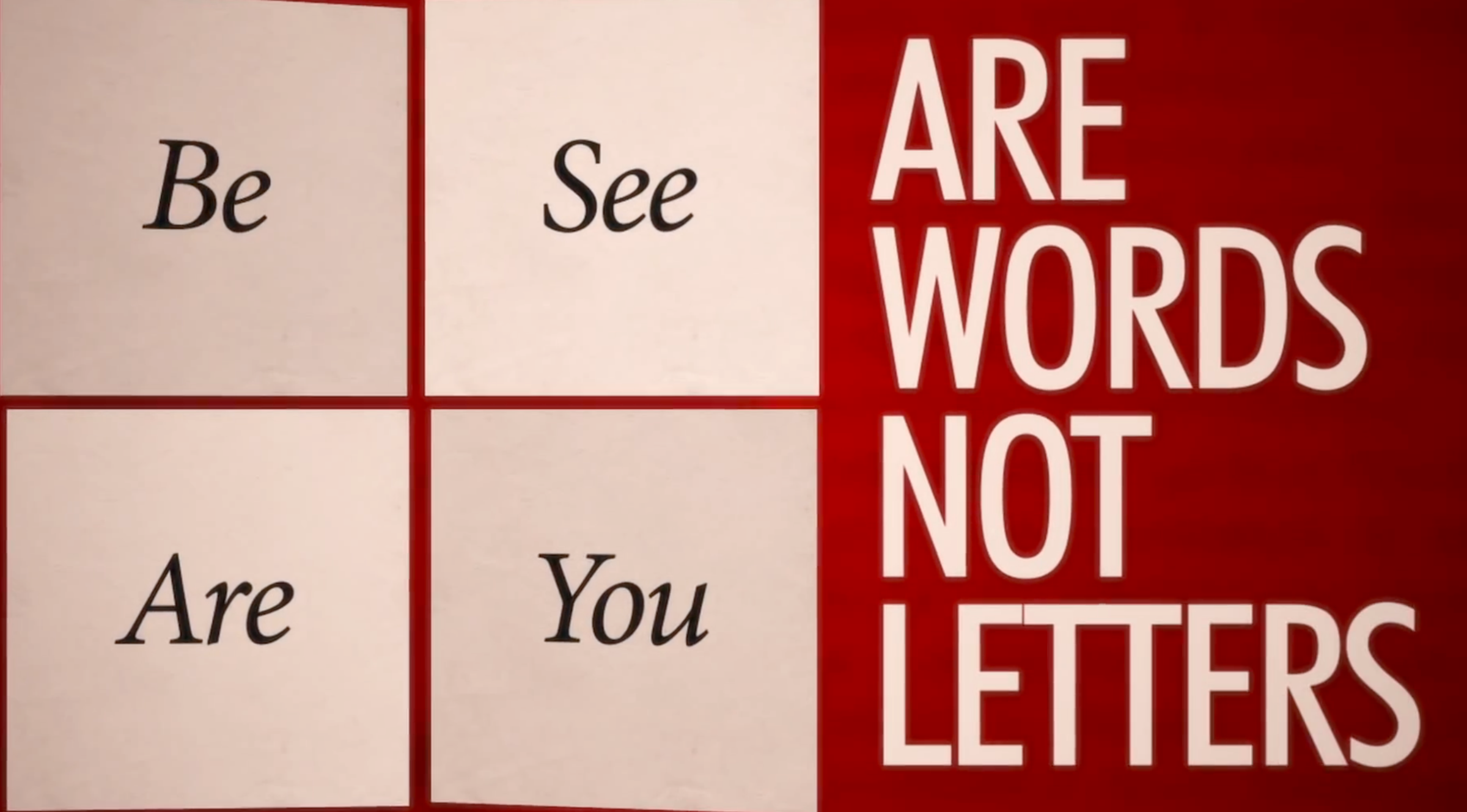

Yankovic decries the texters’ shorthanding of words into letters: be into B, see to C, are to R, you to U. Given that Twitter permits only 140 characters for a message, the truncation is really thrift. Besides, as Yankovic notes in the song, Prince is probably the prime culprit, having slapped such titles as “I Would Die 4 U” and “Take Me With U” on his ’80s hits. The trope goes back further, to the 1955 novelty tune “I-M-4-U (I Am for You),” written for TV host Jack Paar by Sev F. Marino and José Melis and consisting entirely of letters and numbers. So who do we blame? No. Whom?

“Pronoun trouble!” — as Daffy Duck quacked to Bugs Bunny in the 1952 Chuck Jones cartoon Rabbit Seasoning — is rampant these days, and probably always has been. Though I try to avoid it in writing, I wouldn’t guillotine those who use who colloquially for whom, particularly when whom masquerades as the subject of a sentence, as in Who Do You Trust? (a ’50s game show hosted by Paar’s successor as The Tonight Show host, Johnny Carson) or Ray Parker Jr.’s No. 1 1984 movie theme “Who ya gonna call? Ghostbusters!” I do agree with the “Word Crimes” proscription: “Always say ‘to whom.’ Don’t ever say ‘to who.'” And don’t fall for the fake gentility of I as an object. “Between Weird Al and I” may sound elegant, swellegant (in Cole Porter’s phrase), but grammatically it’s smellegant.

(SEE: A career-long gallery of Weird Al Yankovic photos)

I also sympathize with neophyte writers (neophiters) who confuse its the possessive adjective and it’s the contraction for it is — a mistake to which Yankovic devotes an entire verse. In the phrase “a dog’s life,” the dog is it, so it’s life can seem logical. Logical but wrong. To distinguish between the two, think of the dog as a boy: you wouldn’t spell his as hi’s. So a boy’s life = his life, and a dog’s life = its life.

Weird Al raps: “You should know/ It’s ‘less’ or it’s ‘fewer,’/ Like people who were/ Never raised in a sewer.” Less should refer to collective nouns (less knowledge), fewer to plurals of individual things (fewer brain cells). But that distinction may be a lost cause; I’ll bet that not even Whole Foods has a “10 Items or Fewer” checkout line. And what about doing well (achieving success) vs. doing good (performing benevolent deeds)? In “The Old Dope Peddler,” musical satirist supreme Tom Lehrer paid sarcastic (not ironic) tribute to a drug dealer who was “doing well by doing good.” But that song is more than 60 years old, so the two words may no longer be different from (not different than) each other. And with marijuana legally available in some states, the song may have outlived its comic point.

(READ: A Richard Corliss tribute to Tom Lehrer)

Yankovic commits a couple of his own crimes — as in “Here’s some notes,” which should be “Here are some notes,” for the subject to agree with the verb — and quite a few rhyme crimes. Broadway songwriters Stephen Sondheim (rhymes with rhyme) and Leonard Bernstein (doesn’t) would never approve of pairing proper way with conjugate, or find with online. These are false rhymes, lazy rhymes, blurred rhymes. Virtually every pop songwriter employs them today, but in a comedy song arguing for traditional grammar, they dull the precision of the wit.

Yankovic also stoked a ruckus with this quatrain: “Saw your blog post/ It’s really fantastic/ That was sarcastic,/ ’Cause

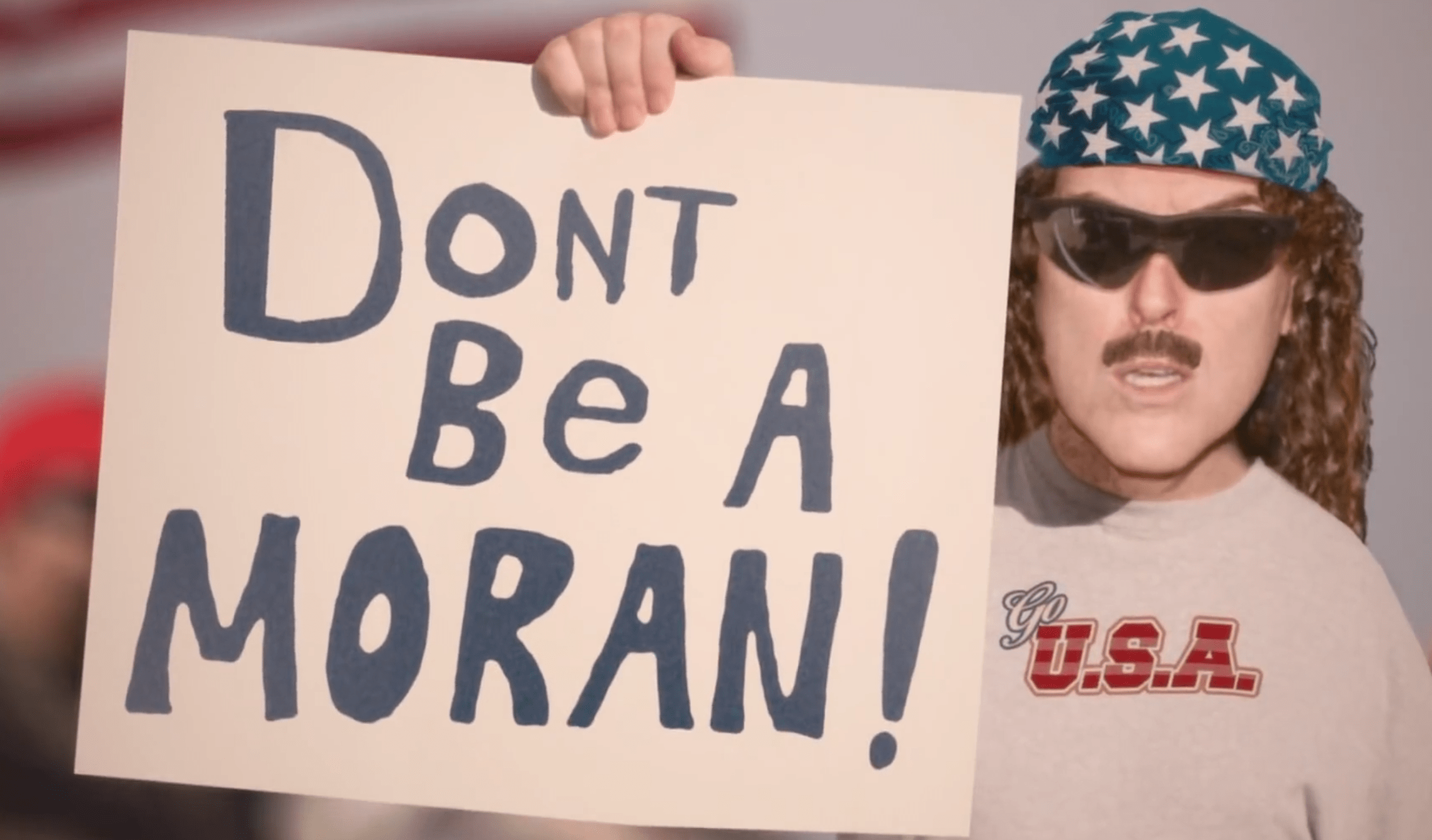

you write like a spastic” — an insult word that also can refer cruelly to those afflicted with cerebral palsy. Yankovic quickly posted: “If you thought I didn’t know that ‘spastic’ is considered a highly offensive slur by some people … you’re right, I didn’t,” he wrote. “Deeply sorry.” Apparently no one has complained about his use in the song of moron, which psychologists once used to describe an adult with the mental capacity of a child. Like idiot, moron has probably passed its sell-by date as an offensive term.

That’s the sticking point about language: it keeps changing. Each person’s sense of grammar probably came from his or her teachers or parents. My mother, a first-grade schoolteacher, instructed her two sons that “between you and I” was wrong, and that the proper way to answer the phone was to say, “This is he.” But she was born in 1907 — for the edification of mathematicians in the room, I was a very late baby — and may have taken syntax cues from her mother, born in the 1860s. One hundred fifty years later, no one speaks or writes like Abraham Lincoln. In Mad magazine in 1956, Doodles Weaver copyedited the Gettysburg Address, amending “Fourscore and seven years” to “Eighty-seven: Be explicit!” Yet today’s teachers indoctrinate their pupils with many rules from Lincoln’s time and long before.

(READ: the complete parody of the Gettysburg Address by scrolling down this webpage)

Those who think we should go with the flow of evolution in syntax — welcome to the 21st century, word codgers — balk at the usage traditions of their very elder elders. I confess that I long avoided the split infinitive (“To boldly go where no man has gone before”), until I learned it was an 18th century codification by an obscure grammarian who thought English should be more like Latin. In that language, infinitives were an unsplittable single word: to split is dilaminare. (Then again, few poets in preceding centuries split their infinitives. Shakespeare didn’t write “To be or to not be?”) Another Latin-derived no-no was ending a sentence with a preposition, which everyone sensibly ignores today. As Winston Churchill, one of the last century’s most powerful writers, wryly observed, “This is the kind of arrant pedantry up with which I will not put.”

Modern grammar has also efforted (one of my favorite faux verbs) to free itself from sexism. Mankind is now humankind, and Gene Roddenberry would surely have rewritten his Star Trek intro as “To boldly go where no human has gone before.” In the ’70s, during the first flush of grammatical feminism, the generic he got modified into s/he. That didn’t take, but the pluralizing of everyone did. The singular pronoun turns plural midway through the sentence “Everyone has their reasons.” I can’t bring myself to write that, so I usually perform pretzel exercises to make the subject plural: “All people have their reasons.”

In my experience, copy editors, like the stalwart staff I’ve worked with and learned from in my 34 years at TIME, are linguistic conservatives — the keepers of the flame ignited by the Strunk-White Elements of Style, published in full in 1957 and chosen by TIME as one of the 100 most influential nonfiction books of the past century. And grammarians tend to be liberal, willing and often eager to promote common usage into acceptable speech.

On a fascinating episode of the Judge John Hodgman Podcast, in which a man brought a complaint against his wife for correcting his grammar, Merriam-Webster associate editor Emily Brewster derided The Elements of Style, saying, “They even break their own rules. They say no split infinitives, and there are split infinitives [in the book].” For adjudication, I turn to TIME deputy copy chief Elissa Englund, who notes, “This isn’t actually true. The Elements of Style discourages it generally but actually says there are times when it is preferable to split an infinitive. (See Chapter V, reminder 2: ‘Write in a way that comes naturally.’)”

(FIND: The Elements of Style among the all-TIME 100 nonfiction books)

Among the bugbears of Kira, the persnickety wife in the Hodgman case, were irregardless (instead of regardless or irrespective) and most importantly (instead of most important). Brewster, as the expert witness on the episode, ruled that the first was now common and the second was new to her. Hodgman then asked Brewster if “I feel badly” was an acceptable equivalent to “I feel bad.” Again, Brewster pleaded ignorance of the distinction, adding, “Those don’t even sound funny to my ear.” (She meant they didn’t sound funny even to her trained ear.) But they should have sounded funny (not funnily). You feel bad, not badly, just as you feel good, not goodly. James Brown didn’t sing “I Feel Goodly,” and a grammar scholar shouldn’t say “I feel badly.” Quick hint: If it doesn’t sound goodly to you, don’t use it.

Liberal grammarians would tell us we live in a democracy, not a kingdom of antiquated rules. I’m a grateful subject of that kingdom, and I’m sure I’ve broken a few of my own rules, which readers are welcome to comment on. TIME’s spell-check always admonishes me whenever I compose a sentence in the passive voice, a warning that is often ignored by me. And the copy editor of a book I wrote for Simon & Schuster corrected my frequent use of years as adjectives (“the 1955 novelty tune …”). I didn’t know that was a word crime, and, between you and I, I keep breaking it.

Nothing in a living language is written in stone. Over the decades, words go from wrong to right. Speak as you will; others will understand you, whatever offenses you utter against hoary tradition. Just realize that the people in a position to hire you, mark your exams or fall in love with you may have stricter standards of written and spoken English. Like Weird Al Yankovic, or the reporters who noted the less and fewer mistake on Greg Maddux’s Hall of Fame plaque, we grammar snobs are listening.

* * *

This is the first in a series of columns in which Richard Corliss drops his usually genial demeanor and assumes the stern tone of the Cranky Guy.

Weird Al Yankovic: A Life in Photos

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com