When President Obama issues executive orders on immigration in coming weeks, pro-reform activists are expecting something dramatic: temporary relief from deportation and work authorization for perhaps several million undocumented immigrants. If the activists are right, the sweeping move would upend a contentious policy fight and carry broad political consequences.

The activists met privately with the President and his aides June 30 at the White House, and say in that meeting Obama suggested he will act before the November midterm elections. They hope his decision will offer relief to a significant percentage of the estimated 11.7 million undocumented immigrants in the U.S. “He seems resolute that he’s going to go big and go soon,” says Frank Sharry, executive director of the pro-reform group America’s Voice.

Exactly what Obama plans to do is a closely held secret. But following the meeting with the activists, Obama declared his intention to use his executive authority to reform parts of a broken immigration system that has cleaved families and hobbled the economy. After being informed by Speaker John Boehner that the Republican-controlled House would not vote on a comprehensive overhaul of U.S. immigration law this year, the President announced in a fiery speech that he was preparing “to do what Congress refuses to do, and fix as much of our immigration system as we can.”

Obama has been cautious about preempting Congress. But its failure to act has changed his thinking. The recent meeting “was really the first time we had heard from the administration that they are looking at” expanding a program to provide temporary relief from deportations and work authorization for undocumented immigrants, says Marielena Hincapié, executive director of the National Immigration Law Center.

The White House won’t comment on how many undocumented immigrants could be affected. “I don’t want to put a number on it,” says a senior White House official, who says Obama’s timeline to act before the mid-term elections remains in place.

Obama has a broad menu of options at his disposal, but there are two major sets of changes he can order. The first is to provide affirmative relief from deportation to one or more groups of people. Under this mechanism, individuals identified as “low-priority” threats can come forward to seek temporary protection from deportation and work authorization. In 2012, the administration created a program, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), that allowed eligible young unauthorized immigrants to apply for a two-year reprieve from deportation and a work permit.

The most aggressive option in this category would be expanding deferred action to anyone who could have gained legal status under the bipartisan bill that passed the Senate in June 2013. According to a Congressional Budget Office analysis, the Senate bill would have covered up to 8 million undocumented immigrants. It is unlikely that Obama goes that far. But even more modest steps could provide relief to a population numbering in the seven figures. “You can get to big numbers very quickly,” says Marshall Fitz, director of immigration policy at the Center for American Progress, a progressive think tank.

One plausible option would be to expand DACA to include some family members of those already eligible. Says a Congressional aide: “While there are several options to provide temporary deportation relief, we expect an expansion of the DACA program to other groups of individuals to be the most clear opportunity.”

It’s hard to pin down how many people this would cover; it would depend on how the administration crafts the order. But the numbers are substantial. According to the CBO, there are an estimated 4.7 million undocumented parents with a minor child living in the U.S., and 3.8 million whose children are citizens. Around 1.5 million undocumented immigrants are married to a U.S. citizen or lawful resident, but have been unable to gain legal status themselves.

Obama could also decide to grant protections for specific employment categories, such as the 1 million or so undocumented immigrants working in the agricultural sector, or to ease the visa restrictions hindering the recruitment of high-skilled foreign workers to Silicon Valley. Either move would please centrist and conservative business lobbies, who have joined with the left to press for comprehensive reform, and might help temper the blowback.

The second bucket of changes Obama is considering are more modest enforcement reforms. Jeh Johnson, Obama’s Secretary of Homeland Security, is deep into a review of the administration’s enforcement practices, and it is likely Obama will order some changes to immigration enforcement priorities. But if these tweaks are the extent of the changes, it would be a blow to activists expecting more. “That’s crumbs off the table compared to the meal we’d be expecting,” says Sharry.

Until now, Obama has frustrated immigration-reform activists by insisting he has little latitude to fix a broken system on his own. To a large extent, he’s right. Any relief the President provides would be fleeting; it’s up to Congress to find a permanent solution by rewriting the law. Deferring deportations does not confer a green card. It only offers a temporary fix.

But legal experts say Obama does have the authority to take the kinds of executive action he is thought to be considering. “As a purely legal matter, the President does have wide discretion when it comes to immigration,” says Stephen Yale-Loehr, an immigration scholar at Cornell University Law School. “Just as DACA was within the purview of the president’s executive authority on immigration, so too would expanding DACA fall within the president’s inherent immigration authority.” According to a recent report by the Center for American Progress, categorical grants of affirmative relief to non-citizens have been made 21 times since 1976, by six different presidents.

Even if Obama is on firm footing from a legal standpoint, he would be wading into political quicksand. Republicans would assail him for extending mass “amnesty” to undocumented immigrants at a moment when the southern border faces an unresolved child-migration crisis. Immigration would become a signal topic in the fall elections, and given that Obama’s handling of the issue has slipped to just 31%, that wouldn’t necessarily favor the President’s party. It would likely damage vulnerable Democratic incumbents in red states, including several whose re-election could determine control of the Senate. And Congress’s incipient failure to reach an agreement on an emergency supplemental bill to address the border crisis muddies the waters even further.

At the same time, Obama will be pilloried by Republicans no matter what he does. Despite the short-term political consequences, in the long run a bold stroke could help cement the Democratic Party’s ties with the vital and fast-growing Hispanic voting bloc. And it would be a legacy for Obama, a cautious chief executive whose presidency has largely been shaped by events outside his control. In the case of immigration, he has the capacity to ease the pain felt by millions with the stroke of a pen.

“There are two ways this could go,” says Fitz of the Center for American Progress. Obama will be remembered as either “the deporter-in-chief, or the great emancipator. Those are the two potential legacies.”

With reporting by Alex Rogers and Zeke J. Miller/Washington

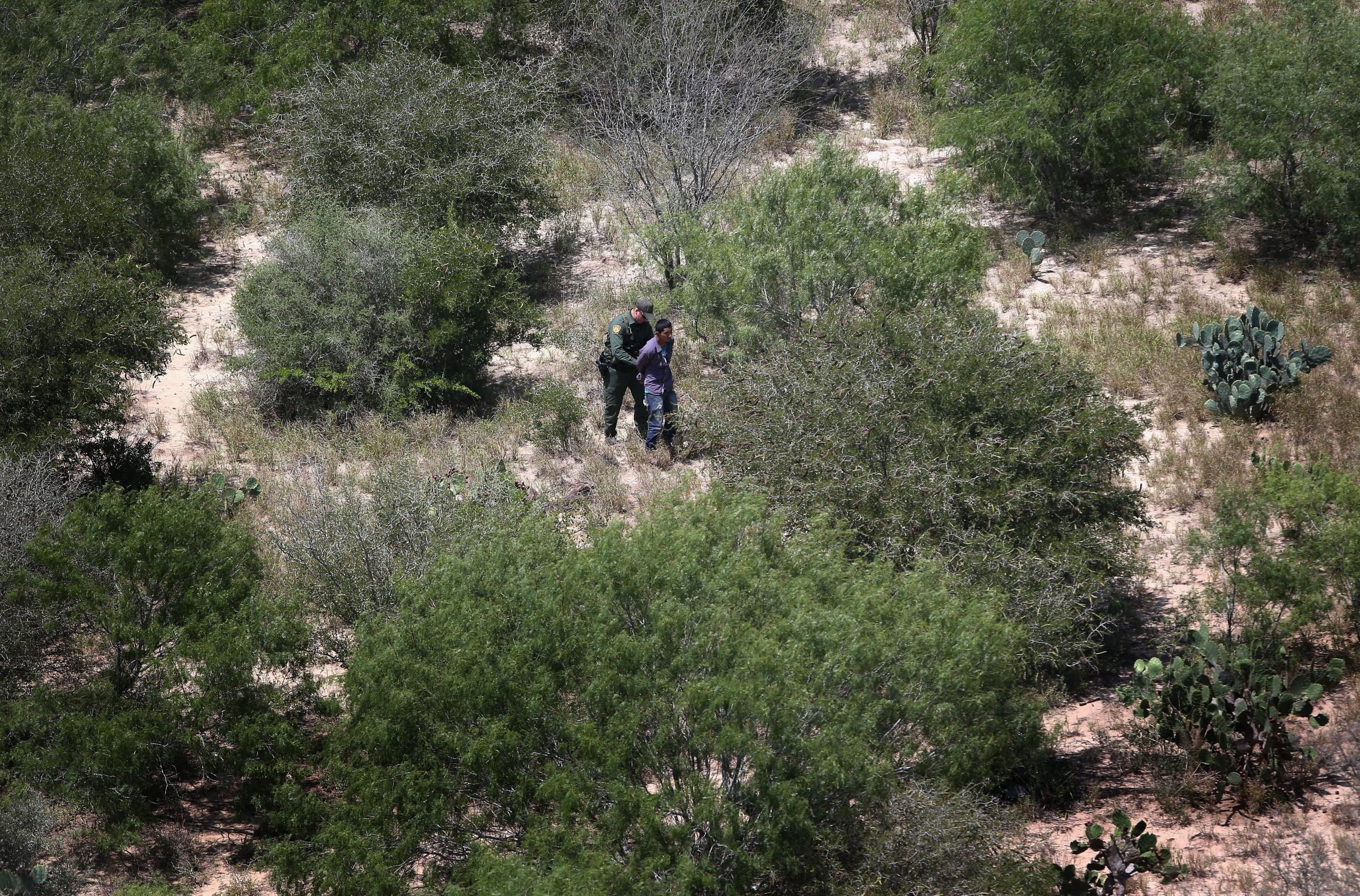

Photographer Captures Birds-Eye View of Border Crisis

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Alex Altman at alex_altman@timemagazine.com