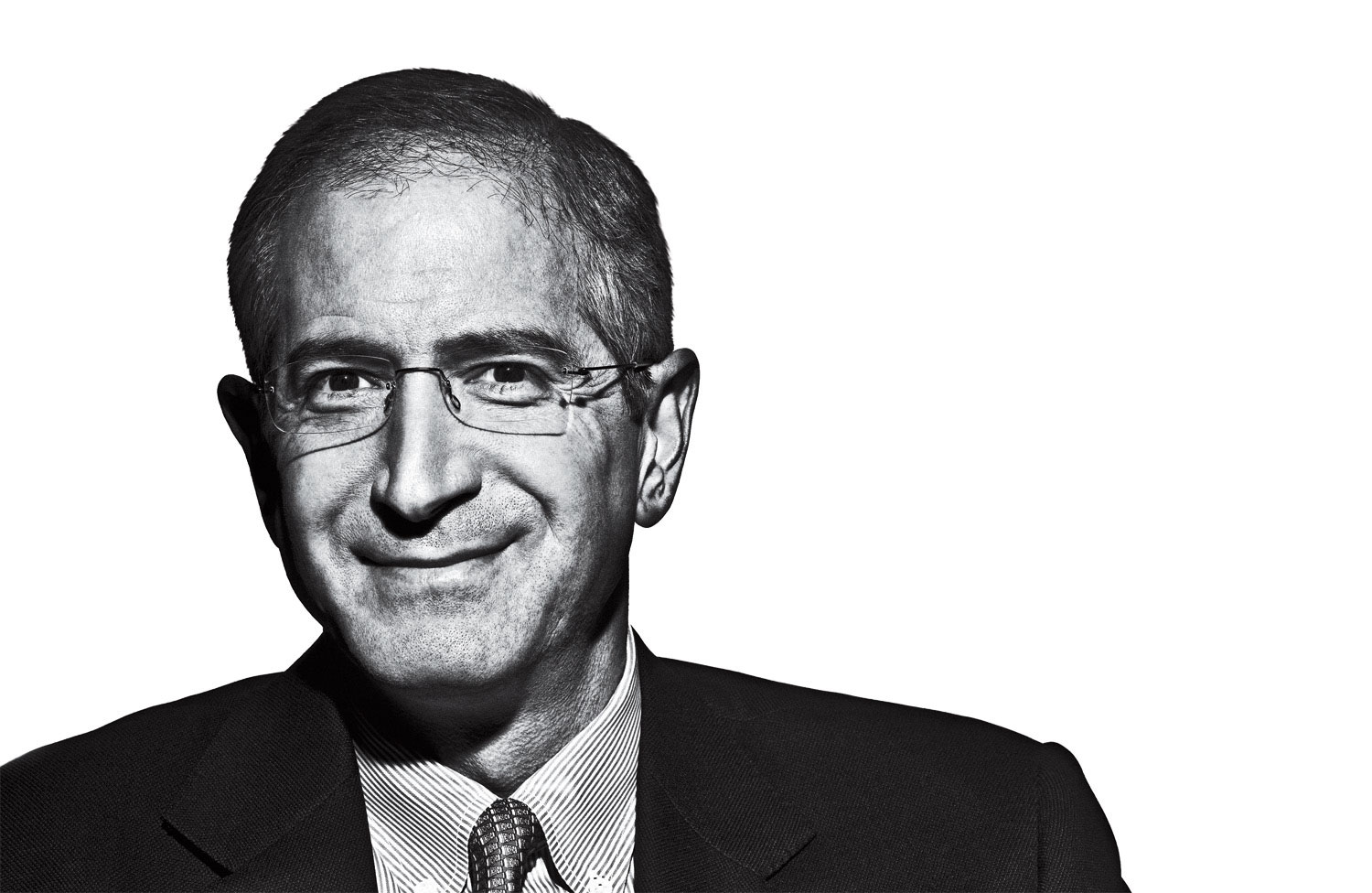

Stooping slightly at the neck, Brian Roberts, the chief executive of Comcast, loped onstage in April at the cable industry’s annual trade show in Los Angeles. Behind rimless glasses, his face looked earnest and likable, more tenured sociology professor than cutthroat mogul. In a country that has long celebrated its tech titans as gurus and geek celebrities—think Steve Jobs in his black turtleneck, Jeff Bezos with his delivery drones—Roberts dresses for the boardroom, a peach tie with his charcoal suit, and utters none of the utopian rhetoric of Silicon Valley. If you met him on the street, you would never guess that he could soon control the U.S. Internet’s most powerful company.

After settling before the audience, Roberts described the revolution that he expects will remake his company in the coming years. Americans today are streaming video on more devices than we thought possible “24 months ago, even 12 months ago,” and that’s not changing anytime soon. People, he said, will watch TV where they want it, when they want it—and it won’t be through an old box in their living room but through smartphones and tablets and any number of slick new screens hooked up to the Internet. “It’s a whole new world,” he said.

What he didn’t say was that he is poised to dominate that new world, however it evolves. His company is already the largest cable outfit in America and the owner of the television behemoth NBCUniversal, with the lucrative rights to broadcast hundreds of live sports events every year. But Roberts’ real trump card is that he owns more of the physical infrastructure—the high-speed digital wires capable of streaming online video to people’s homes—than anyone else in America, and he’s making a play to control even more. In February, Roberts made a $45 billion bid to buy Time Warner Cable, the nation’s second biggest cable company.

If the deal goes through, which most observers expect, Roberts will own, by conservative estimates, 35% of the nation’s broadband Internet connections, and that’s after the company divests a few million users as part of the merger. If you narrow the definition of broadband to include only those connections that would allow a family to watch and record several high-definition videos simultaneously, the same way they’d use a TV, his share of the market could stretch above 60%. The combined company would be nearly seven times the size of its nearest cable rival and the dominant broadband provider in 19 of the country’s 20 top markets. With that sort of market clout, Comcast will have the leverage to demand more money from TV programmers, online video-streaming companies and regular customers—and the power to shape what technologies and Internet services are available, and at what cost and quality, in a large percentage of American homes.

This vision may be good for Roberts’ business, but it’s causing some queasy feelings in corporate suites from Hollywood to Silicon Valley to New York City, where rival media and telecom companies have been scrambling to find a way to compete in Roberts’ new landscape. AT&T recently announced it will buy DirecTV, the biggest satellite-TV company in the country, and in June, Rupert Murdoch’s sprawling media empire, 21st Century Fox, floated the idea of snapping up the movie and television giant Time Warner—a move that would give Murdoch the scale he needs to hold his own with Roberts during negotiations over everything from cable carriage fees to channel placement. (Time Inc., the owner of this magazine, became independent of Time Warner in June. Time Warner Cable is independent of both companies.)

Reed Hastings, the CEO of Netflix, the largest online video-streaming company, has warned his own investors that Comcast is already using its “anticompetitive leverage” to extract fees from web companies in exchange for allowing them access to American homes. The comedian turned Senator Al Franken says he’s heard from content producers who are worried that the merger will make Comcast powerful enough to essentially decide which TV networks even exist. If the company refuses to carry a show, it could be a fatal blow.

In his typically low-key way, Roberts has patiently dismissed all of these concerns. An even bigger Comcast, he says, will mean more money to spend developing new technologies, improving customer service and investing in the digital infrastructure that wires our country from coast to coast. Comcast’s stronger position at the negotiating table will be a boon to customers too, he says, by allowing the company to bid down how much it pays TV networks to carry their channels. The merger, he promises, will be “a win for everyone.”

The recent record, however, suggests the story will be a bit more complicated. Comcast has raised customer prices by an average of more than 4% every year since the mid-’90s, a trend that Comcast executives say won’t end anytime soon. “We’re certainly not promising that customer bills are going to go down,” Comcast’s executive vice president David Cohen told reporters in February. This year, the American Customer Satisfaction Index rated Comcast and Time Warner Cable the worst two companies in any industry nationwide.

Economists, meanwhile, worry that further mergers will reward an industry that is among the most expensive, by comparative download speeds, in the developed world. For example, for the price and quality of 45-megabit-per-second (Mbps) download speeds, U.S. broadband ranks 30th out of 33 developed countries, according to a recent report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. In Hong Kong, 500 Mbps costs $35 per month; in San Francisco, Comcast’s fastest download speed, 105 Mbps, runs you $114.95.

Public frustration aside, the only real obstacle in Roberts’ way is a few hundred government employees in Washington who are scrutinizing the deal for antitrust implications and consumer-interest concerns and will decide this fall whether it passes muster. To win them over, Roberts has amassed one of the largest lobbying and political-influence operations ever created. At the same time, in his trademark modest way, he has continued to publicly dismiss any suggestion that his business plans should raise public concern. “We want to lead, to innovate,” he told one reporter recently. “Why is this controversial?”

The Next Internet

For most of the past 25 years, no single person or company has been powerful enough to control how the American Internet works. One reason for that was the diffuse and chaotic nature of our online economy—a kind of rough-and-tumble Wild West where thousands of producers jostled for the attention of the masses. In this environment, no single company, not even Goliaths like Google or Facebook, dominated enough traffic to bend the network’s free-market checks and balances.

The infrastructure of the Internet helped keep everyone on a level playing field as well. All players, from pip-squeak individuals to giant companies, had to pay an Internet service provider (ISP) a flat fee, based on the speed or volume of the service, for online access. In exchange for those fees, the ISPs would expand and maintain their pipes and pass their customers’ traffic to and from another set of companies that owned the larger, global transit ways for online information. It was, for a time, a marvelous architecture, fundamentally unlike any of the other networks in our lives. There was no government ownership as with the interstate highway system, no costly long-distance plans as with phone networks and no individual postage required to send content as with the U.S. Postal Service.

But in recent years, that unique structure has started to crack, and the reason is the size of the biggest players. A decade ago, thousands of companies shared in the daily buzz of Internet traffic, said Craig Labovitz, the CEO of DeepField, a network-research firm. By 2009, 150 companies accounted for half of all that traffic, and by early this year, just 30 companies made up the majority of the daily give-and-take. As of March, just two companies in particular—Netflix and Google, which owns YouTube—accounted for 47% of all Internet traffic during prime-time hours at night, according to Sandvine, a network-equipment company.

Meanwhile, ISPs like Comcast have consolidated as well. Part of the reason was old-fashioned mergers, with big cable and telecom companies buying up smaller ones, and part of it was that the market for broadband simply changed. Online video consumption grew by 71% in the U.S. from 2012 to 2013, according to Nielsen. Since you need at least 5 Mbps to stream a single HD video, according to the FCC, Americans’ demand for faster broadband exploded. As a result, ISPs that offered perfectly acceptable speeds less than a decade ago have fallen out of favor. Dial-up is laughable. Satellite is too unreliable. DSL is on the decline. And while there is a proliferation of faster mobile services like 4G and LTE, most come with data-usage caps that make them unattractive to use as a household’s primary Internet connection.

Verizon and AT&T, both of which are bleeding traditional DSL subscribers, have begun offering customers speedier services like FiOS and U-verse. But those, along with lightning-fast options like Google Fiber, are available in only about 20% of American homes. The rest of us are left with one choice for broadband capable of streaming multiple HD videos: cable. And since cable companies almost never compete with one another geographically, that means most Americans have one option for that fastest available category of broadband.

Though some analysts predicted as recently as a decade ago that cable was a terminal industry, the opposite has turned out to be the case. While pay-TV subscriptions are slowly declining, broadband subscriptions are driving new profits. Broadband is Comcast’s fastest-growing sector, with margins that are, says industry analyst Craig Moffett, “comically profitable.”

While undoubtedly good for the cable industry, this paradigm—more demand for streaming videos, more demand for faster broadband, fewer companies offering service that meets those needs—sets the stage for a power struggle. In one corner are enormous content producers like Fox, Time Warner and Netflix. In the other are powerful ISPs like Comcast. The stakes? Control over the Internet and the profits it produces.

Battle of the Titans

This fight for cash turns on what goes through the pipes and who pays for it. The biggest ISPs, including Comcast, say that since their wires are being clogged up by just a handful of the big content producers, those big content producers should pay them for access. But several of the big content producers say the ISPs are taking advantage of near monopoly conditions and demanding tolls from companies that have no choice but to pass through their pipes to reach customers.

This central tension rocketed into headlines last year after customers began streaming more Netflix shows and overloading Comcast’s network, causing the videos to buffer and sputter and not play at all. Netflix CEO Hastings, worried that such technical difficulties would cause customers to drop their Netflix subscriptions, agreed in February to pay Comcast to ensure that Netflix’s content was speedily delivered. But he also cried foul. He argued that since most Americans don’t have much choice of providers that offer broadband fast enough to stream video at home, Comcast could simply allow its customers’ online access to degrade without worrying that they’d switch to another ISP. Comcast can use that “anticompetitive leverage,” he said, to extort fees from Netflix and other web companies. It’s Comcast’s responsibility, he argued, to expand and maintain its pipes in order to provide customers with the access for which they are already paying. “They want the whole Internet to pay them for when their subscribers use the Internet,” Hastings said.

Roberts, in his affable way, disagreed. He said Netflix, which now accounts for more than a third of the traffic on Comcast’s pipes at night, is just trying to avoid bearing the costs of streaming the volume of Internet traffic that its shows generate. Netflix “used to spend three-quarters of a billion dollars for postage” to send DVDs to customers in the mail, Roberts said. Why shouldn’t it pay that same “postage” to Comcast for sending its content online?

Silicon Valley tech firms both in and out of the streaming-video business have since spoken up, too, saying Comcast’s leverage is likely to grow further with the release of its multifaceted new Internet-connected cable box, X1, which does more than stream TV. The X1 allows you to adjust your thermostat, turn down the lights, map your friends’ locations from their smartphones and stream your kid’s soccer game live from someone else’s iPhone—all while tweeting about it. Any other company attempting to compete in that rich new market, known collectively as the Internet of Things, will inevitably be dependent on Comcast’s pipes to reach at least 35% of the broadband market. Left unanswered is under what circum-stances those companies, like Netflix, will be asked to pay Comcast to connect to their network on the back end, how much they will have to pay and whether those fees will preclude their entry to the market.

There is a similar but distinct fight brewing over the rules that govern the last mile of Internet service, the connections between ISPs and customer homes. The FCC has begun drafting a new set of rules designed to address Net neutrality, the idea that ISPs must treat all web content equally in that final stretch of pipe. The idea behind Net-neutrality rules is to prevent an ISP from, say, allowing MSNBC content to stream more easily than a Fox News segment. As part of its merger with NBCUniversal, Comcast agreed to abide by Net-neutrality rules until 2018. President Obama has also sworn to voters that he would hold these principles sacrosanct.

But then in April, FCC chairman Tom Wheeler, an Obama appointee, proposed a new set of Net-neutrality rules that allow ISPs to give preferential, faster treatment to content from companies that pay them for the privilege. Critics, including nearly every major Silicon Valley tech firm—Google, Facebook, eBay, Amazon, you name it—have howled that those provisions will create a “fast lane” on the Internet for rich companies able to pay the price and a “slow lane” for everyone else. That will give the richest incumbent companies an advantage while squeezing out the next generation’s innovators—tiny startups coding on a shoestring.

While Comcast has promised not to block or hamper access to any website and the FCC is vowing to monitor all ISPs for anticompetitive practices, tech companies say there’s plenty Comcast can do to make accessing some sites more difficult, or expensive, while staying within the rules. Will people be able to stream shows more easily through X1 than through competing devices, like Apple TV, that must use Comcast’s broadband? Will Comcast’s pricing structure make it simply unaffordable to stream videos through broadband? The answers may not be known for years.

In the meantime, Comcast has been repeating its commitment to enforce Net neutrality in ads promoting the merger. But the company has made no promise to extend that commitment beyond 2018 if the merger goes through. Rather, Comcast echoes the “open Internet” rhetoric of Wheeler and has joined others in the industry in pushing against any stronger regulation that would require broadband companies to treat all the content coming over all their wires equally.

The Influence Game

In the early 1960s, Brian Roberts’ father Ralph Roberts, who had tried his hand as a young man selling everything from belts to Muzak, bought a small cable company that served 1,200 homes in Tupelo, Miss. It was a tough business to get off the ground. Local leaders and city councils, which had the power to tightly regulate cable as they did other utilities, had to be cajoled to invite new cable franchises to wire their towns. In this climate, the famously charming Ralph Roberts, now 94, quickly learned that having friends in high places could be a major boon for business. It’s a lesson that his son Brian, who joined the family company as a young man in the late ’70s, quickly learned too.

Up until the mid-’80s, when Congress passed a law deregulating the cable industry, the lobbying game was played in local and regional halls of power, but over the next two decades, as Comcast grew in size and clout, so did its presence inside the Beltway. Ever since Brian Roberts, who’s now 55, became CEO in 2002, Comcast has been one of the biggest players in the Washington circuit. Last year it spent more on lobbying than any other company in the U.S. except Northrop Grumman, the defense contractor that makes the B-2 bomber. So far this year, Comcast has signed with more than 35 firms around town, hiring a total of 114 lobbyists, including five former members of Congress and a former FCC commissioner.

Meanwhile, the company spread several million dollars’ worth of campaign donations to nearly 250 members of Congress this election cycle alone, reserving the biggest gifts for those who serve on the committees that regulate telecom. The Comcast Foundation has been busy writing checks too. Last year it gave nearly $17 million to nonprofits—generosity that is not without political perks. During Comcast’s last big merger, with NBCUniversal in 2011, at least 54 groups that received Comcast cash wrote letters to the FCC in support of their benefactor or otherwise publicly endorsed the deal. This year a university professor who testified before Congress on Comcast’s behalf hailed from a think tank funded in part by Comcast cash.

This delicate dance of soft power is not, of course, unique to Comcast. Google, Amazon and Facebook are dumping tens of millions of dollars into “government-relations campaigns” too. But one thing Comcast has going for it is decades of history on Capitol Hill—a past that has earned it a Rolodex of well-connected friends. The head of the cable industry’s trade group, the National Cable and Telecommunications Association (NCTA), Michael Powell, used to be the chairman of the FCC, and current FCC chairman Wheeler used to be the president of the NCTA. Oh, and another former president of the NCTA is Roberts, whom Obama personally appointed to the President’s Council on Jobs and Competitiveness in 2011. The pair spent a day together last August at Roberts’ Martha’s Vineyard estate.

While both Roberts and his wife have given hundreds of thousands in political contributions, it pales in comparison with the several million that Comcast’s man in Washington, Cohen, has bundled in campaign contributions over the years. At a fundraiser for Democratic Senate candidates at Cohen’s home in Philadelphia last fall, Obama joked, “I have been here so much, the only thing I haven’t done in this house is have seder dinner.” In February, Cohen attended a White House soirée in honor of French President François Hollande. The company is “totally ubiquitous, all the time, everywhere, behind the scenes,” former FCC commissioner Michael Copps says.

Neither those personal connections nor piles of cash guarantee, of course, that the Justice Department and the FCC will simply approve the merger. But all that influence, as it’s known, does tend to make it difficult to criticize a friend. Congress, which does not have a direct say over the federal regulators’ review, could raise hell about the merger, ignite public outrage and threaten to pass new laws, but there is little sign of an uprising. Obama, who appointed Wheeler, could make a fuss about the new Net-neutrality rules too, but he has so far dodged the spotlight, issuing bland statements about the “independent” agency Wheeler runs.

The Justice Department, for its part, is currently scrutinizing the merger for potential antitrust implications—an art more than a science in an era in which staggering consolidation has once again become the norm. Comcast and Time Warner Cable have argued that since they do not compete in any geographic region, anticompetitive concerns are a nonissue. That metric does not, of course, take into account the breadth of Comcast’s reach, from cable, telecom, broadcast and TV programming to broadband Internet and new media, but no matter. Analysts in all of those markets generally agree that the Comcast merger is likely to get a green light later this year.

The future, in other words, is shaping up just as Roberts predicted. The goal, he told a reporter recently, is to get as many people as possible to “engage with us, to take advantage of this technological explosion.” “We are in many, many homes. We offer the fastest Internet today,” he said. “The more consumers want speed, the better it is for our company.” On that final point, no one would disagree.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Haley Sweetland Edwards at haley.edwards@time.com