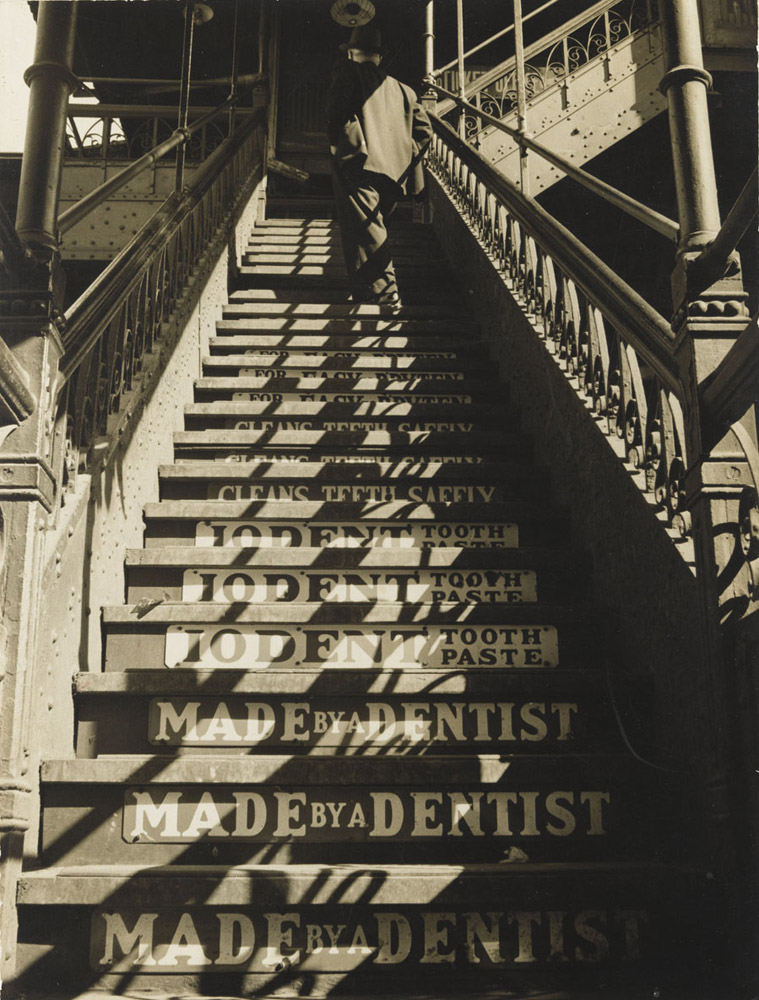

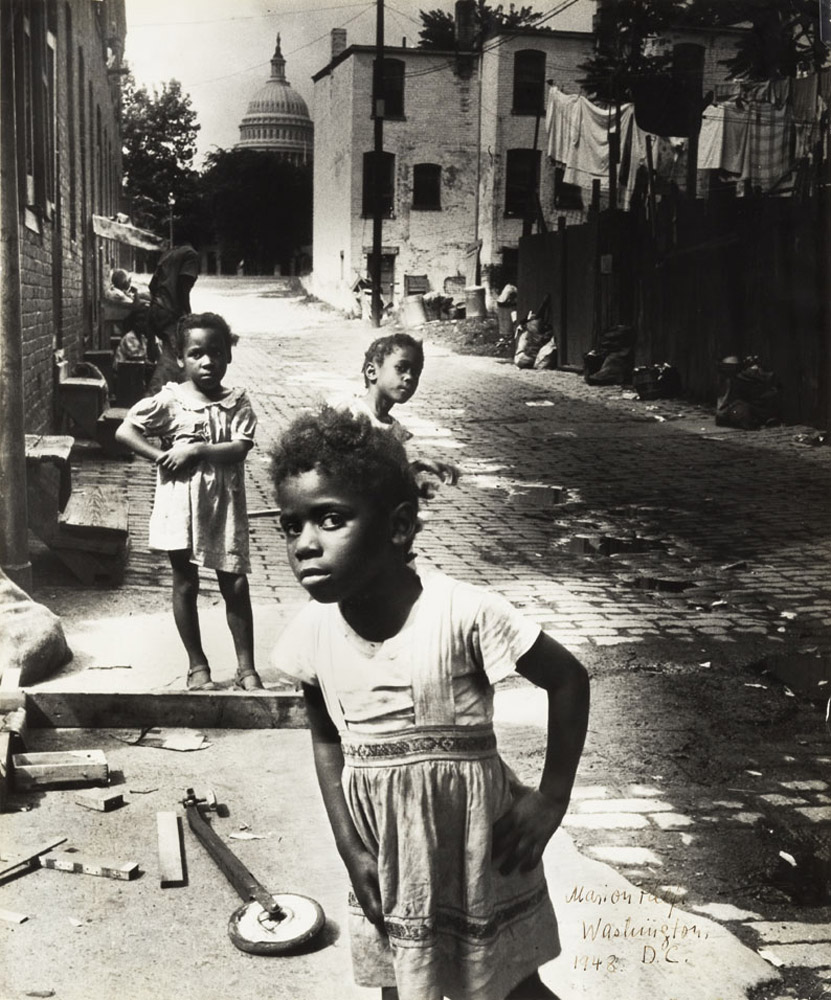

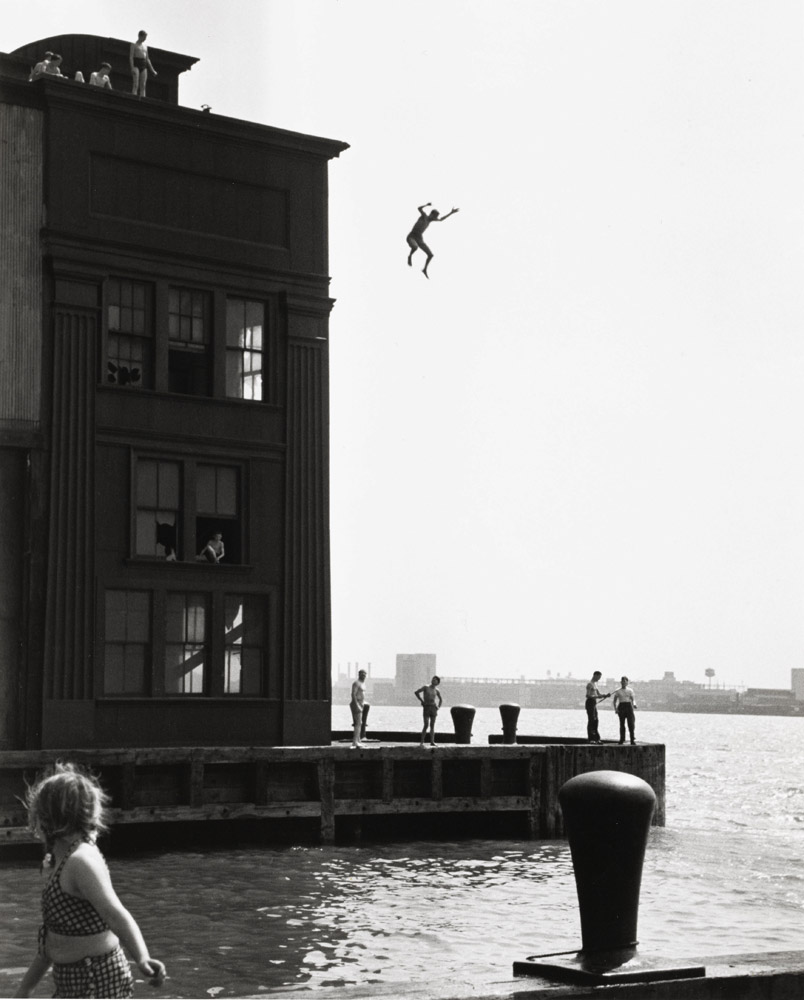

A game of hopscotch. A toothpaste ad. Filthy slums. This, for better or worse, was New York life in the 1930s. Many looked but few saw until the Photo League—a pioneering group of young, idealistic documentary photographers—captured that life with cameras.

The Manhattan-based League, which incorporated a school, darkroom, gallery and salon, was the first institution of its kind when it was founded in 1936 says Mason Klein, curator of fine arts at The Jewish Museum, which is currently presenting “The Radical Camera,” an exhibition in collaboration with the Columbus Museum of Art in Ohio. “There was nothing like the Photo League, where people could exhibit their work, students alongside their mentors, be taught a kind of history of photography and start understanding what the meaning of the photograph might be.”

Many of its founding members, including Sid Grossman, Sol Libsohn and Aaron Siskind, were first-generation Jewish immigrants with progressive, left-wing sensibilities. “They were very conscious of neighborhoods and communities,” says Klein. “I think it was very natural for Jews to form an egalitarian group and understand that the ordinary citizen of the urban scene was as much a valid subject as any for photography.”

The League thrived for fifteen years, generating projects like the Harlem Document, a collaborative effort by ten photographers to document the living conditions in poor black neighborhoods. It also fostered the careers of notable photographers such as Lisette Model, Weegee and Rosalie Gwathmey.

Despite its progressive agenda, the League’s mission was far from simplistic. Founder Grossman, who was just 23 when the group started, encouraged its members to look beyond documentary and question their relationship with the image. “Sid taught people to challenge their habitual ways of seeing the world,” says Klein. “A more poetic and metaphoric expression of how one saw the world was what Sid wanted from his students.” Under Grossman’s guidance, the League’s young muckrakers became artists.

By the 1940s, the League had turned away from its narrow political focus, capturing the squalor and splendor of everyday New York. The country was moving in the other direction, however, zeroing in on those suspected of harboring leftist sympathies. On December 5, 1947, the U.S. Attorney General blacklisted the League as “totalitarian, fascist, communist or subversive.” In 1951, it closed its doors forever.

The League’s reputation has never truly recovered, says Klein. “They were condemned to a kind of ideological shelving and, I think, unfairly treated by history. We’re trying to rectify that with this show, because they really were always about pushing the photograph and understanding it as art.”

The Radical Camera is on display at The Jewish Museum in New York through March 25.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com