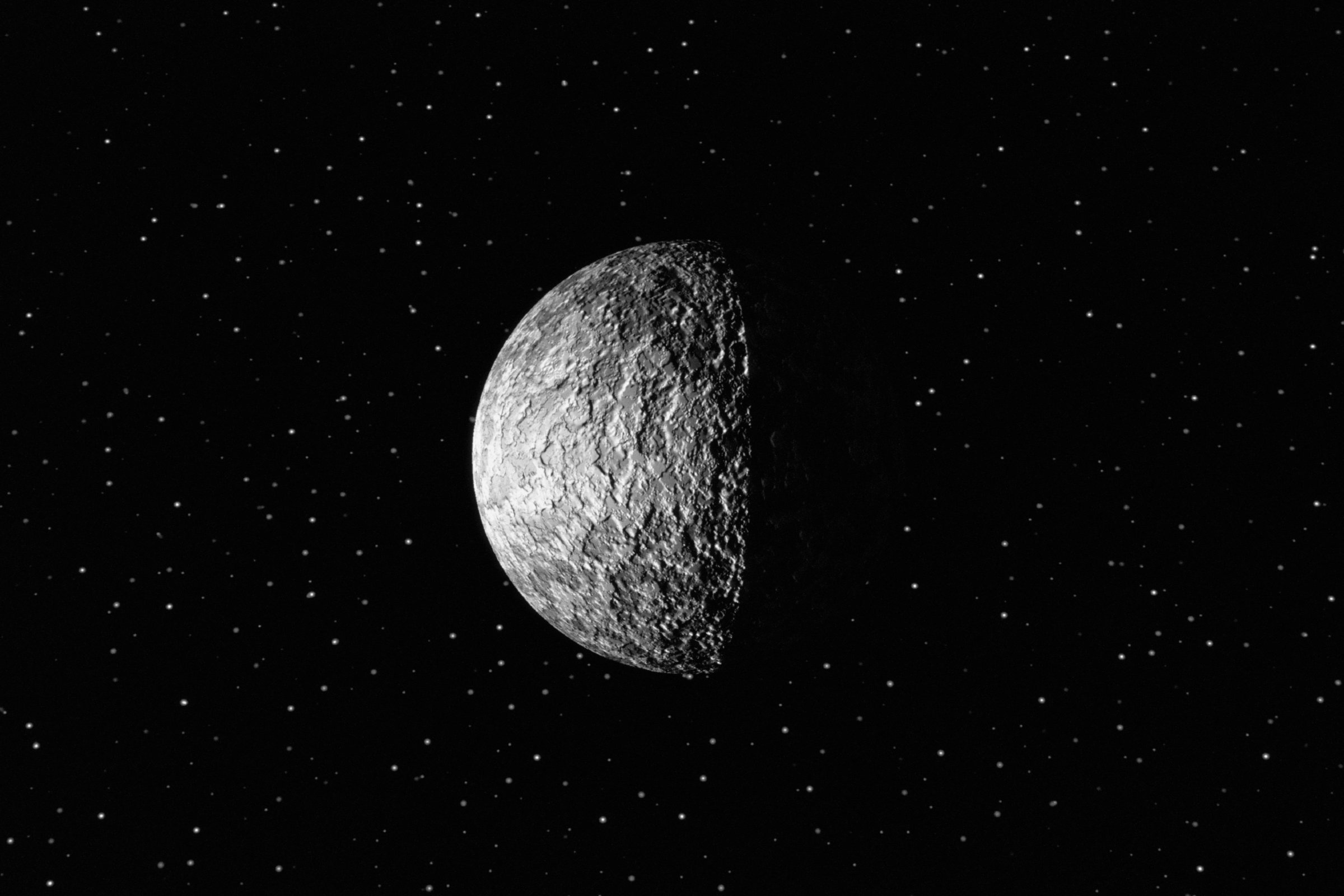

It will be a very big deal when NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft finally arrives at Pluto next July, after a nine-year, four-billion-mile-plus journey. Sure, the tiny, icy world was demoted from “planet” to “dwarf planet” a few months after launch, but being shuffled ignominiously into a lesser category doesn’t make Pluto any less interesting. Once considered to be a weird little world orbiting alone at the edges of the Solar System, it’s now recognized as just the biggest member (more or less) of a huge swarm of frozen objects known collectively as the Kuiper Belt. A close look and a barrage of scientific measurements of Pluto and its moons could give astronomers all sorts of information about a totally unexplored part of the Sun’s immediate neighborhood.

But once you’ve spent $700 million on a space probe, it’s a shame to let it go idle after zipping past its prime target. All along, therefore, New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, has been planning to visit a second Kuiper Belt object (or KBO) after the Pluto encounter. The problem: while planetary scientists are sure there are billions of KBO’s out there, they’ve only identified 1,500 or so over the past 22 years—and none of them is on New Horizons’ projected trajectory.

The problem is that KBO’s are so vanishingly faint that even the most powerful telescopes have trouble picking them out. In the last few years, Stern and his team have joined the hunt, hoping to increase the haul. “We started searching using very large ground-based telescopes like the Keck and the Subaru,” says Stern, “but it’s a very tough, state-of-the-art problem.” They’ve actually discovered more than 50 new KBO’s this way, but those too are nowhere along the route the space probe is flying. Statistically speaking, says Stern, “we need about twice that many overall to get one or two in the bag to choose from.”

That being the case, Stern and his team have been lobbying for time on the Hubble Space Telescope to try and pinpoint a likely target—and the telescope’s stingy Time Allocation Committee has finally said yes (they’re stingy by necessity, not meanness: the number of requests from astronomers for observing time is vastly more than the Hubble can handle).

Stern and his crew will now get 200 orbits of the Hubble, each lasting about 90 minutes, to search for New Horizons’ next stop. There’s a catch, though says Stern. “We get 40 orbits right off the bat, but we have to find at least two new objects in that time or they don’t give us the other 160.”

They have to do it soon, too. It’s pretty much impossible that there will be any KBO literally on New Horizons’ flight path, so the probe will have to fire its engines to adjust its trajectory slightly. “We have to fire right after Pluto,” says Stern, “and in order to do it accurately we have to track the new object for months to account for its orbit. We have to find the object by the end of the summer, more or less.”

Even with the Hubble, there’s no guarantee of success. “There’s no shortage of KBO’s,” says Stern. “But finding them is really, really difficult.” If they beat the end-of-summer deadline, though, scientists will have a second shot at trying to understand what goes on at the very edge of the Solar System, which will be a very good thing. It will likely be a long time before humanity comes out this way again.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Your Vote Is Safe

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- How the Electoral College Actually Works

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- Column: Fear and Hoping in Ohio

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com