This post is in partnership with Consequence of Sound, an online music publication devoted to the ever growing and always thriving worldwide music scene.

Ten years ago, I hung a poster on my wall that read, “Being the adventures of a young man whose principal interests are rape, ultraviolence and Beethoven.” It was a replica of a vintage ad for the film A Clockwork Orange, purchased in a plastic laminate from my local punk supply store. Kubrick’s adaptation of the Anthony Burgess novel goes like this: A 15-year-old serial robber and rapist named Alex murders a woman, then opts for psychological rehabilitation over prison time. The rehab accidentally conditions him to hate his favorite music, destroying even the innocent parts of his identity. The story concludes that in order to be fully human, men must be free to choose to murder. Never mind the collateral damage of, say, dead women. You can’t prevent criminals; you can only punish them.

Lana Del Rey appears at her most complicated on her second album, Ultraviolence. On the title song, she sings from the throes of a physically abusive relationship. She repeats the title of “He Hit Me (And It Felt Like a Kiss)”, a song written in 1962 by Gerry Goffin and Carole King, recorded by The Crystals and Phil Spector, and later disowned by King. Del Rey sings about a man who nicknames her “poison” and “deadly nightshade,” then hits her in a way that makes her suspect it’s a sign of true love. She hears sirens, either the kind that signify emergency or the kind that lure you to be dashed against the shore. She hears violins and violence in the same word. “I could have died right then ’cause he was right beside me,” she sings, her voice multi-tracked over itself. Died of love, or died of him? Is there a difference?

Aided by the production talent of The Black Keys’ Dan Auerbach, Ultraviolence presents an endlessly fascinating cornucopia of dysfunction. Del Rey’s voice flourishes. Inside the album’s big, vintage swing, she sings herself into places that Born to Die, with its pop veneer, couldn’t touch. Her lyrics supply a wonderful foil to The Black Keys’ most recent outing, Turn Blue, which ended on the conclusion that “all the good women are gone.” Damn right, Del Rey seems to sneer. Here’s a gallery of the bad ones.

Both Del Rey and Auerbach draw upon signifiers of 20th-century culture, but their motivations for looking back seem miles apart. The Black Keys find comfort in the 1970s. They’ve adopted a mode of playing and writing that’s well-trod and easy to recall fondly. Ultraviolence, meanwhile, sounds nostalgic. It doesn’t loop back through the roles played by last century’s women singers, though Del Rey wields classic femininity as an aesthetic weapon. Here, she dons a genre that once framed an idealized vision of female longing and fills it with all those other women: the women implied by the songs that men were singing about, the women that served as fodder for generations of male heartbreak.

Shedding the tight choruses and hip-hop samples that propelled her debut, Del Rey now plunges fully into the 21st-century impulse to fetishize 20th-century culture. “They say I’m too young to love you,” she simpers on “Brooklyn Baby”. At first it sounds like she’s talking about an older man, but it turns out she’s talking about a whole bunch of them: Lou Reed, the Beats, the first generation of jazz musicians, and so on. The song’s not about Brooklyn 30 years ago, that long-gone, ideal Brooklyn where artists lived fast and cheap. No, it’s about Brooklyn now, a confused, living museum that honors its own geographical memory through a bizarre cultural cannibalism. “I’m a Brooklyn baby,” she sings. “If you don’t get it, then forget it.” This is by far the most millennial song ever written.

(Read: Lana Del Rey Is More Interested In Space Than Feminism And That’s Okay)

Throughout Ultraviolence, marks of old culture surface and then disappear. Chevy Malibus course down the California coast, women wear pearl necklaces and curlers in their hair, and even Hemingway shows up briefly alongside Burgess. Del Rey controls their orbit like she’s injecting herself into all the art that she consumed long after it had faded from the zeitgeist. And she is. Her re-imagining of the past with her at its center comes out of necessity, not comfort. All those women that rock stars sang about? They were real people, and we never heard their side of the story. Del Rey sings in that void. Thanks to her words, her voice, and her inscrutable presence, she gives those women inner life.

“I’m fucking crazy,” she insists on “Cruel World”. “I want your money, power, and glory,” she demands on “Money Power Glory”. “I fucked my way up to the top,” she brags on a song titled, naturally, “Fucked My Way Up to the Top”. “This is my show.” In a series of delightfully Kanye-reminiscent maneuvers, she preempts the worst of her critics.

Del Rey braves huge and often absurd gestures, but my God, does she sound like she means them. The chorus of “Money Power Glory” arcs with her most triumphant melody yet, while “Shades of Cool” and “West Coast” shiver with heartbroken soprano. She’s never sung like this before. The characters and artifacts that surround these songs feel artificial, like stock props, but the music that Del Rey pulls them through splits them open, shakes them to life. She walks that tough line of high melodrama, demanding emotional investment in stories that nakedly display their own falseness. The way she sings, you start to guess that there’s real love somewhere inside all that gloss.

That love seeps hardest from one of the trickiest songs to scan, the slow-burning, string-laden “Old Money”. The second-to-last track on the album, it hits the same sweet pathos of “Young and Beautiful”, Del Rey’s recent contribution to the soundtrack for Baz Lurhmann’s The Great Gatsby. Maybe “Old Money” takes place inside the same fiction. The way it places wealth next to loss, material possession next to emotional lack, I think it might. It sounds like it’s sung through Daisy Buchanan, Gatsby’s lost love whose story was only ever told by the men around her. In a way, Del Rey lends even more life to that character than Carey Mulligan did on camera. “I’ll run to you, I’ll run to you/ I’ll run, run, run,” she sings in a timbre that by itself crystallizes Daisy’s paradoxical desire and warm, subtle sadness, a sadness that F. Scott Fitzgerald used to symbolize an American betrayal that’s still going on.

(Read: Lana Del Rey’s “Summertime Sadness” Is A Fake Radio Hit)

I keep looking deeper into Ultraviolence because I want to understand what Del Rey is trying to understand. I want to know why the culture around me keeps grasping at past emblems — why advertising for 40-year-old movies still decorates college dorm rooms, why I can make my iPhone look like a Polaroid, why 90,000 people sing along to roots rock at Bonnaroo. I want to know why we reuse these tropes uncritically, reaching for analog without asking what gives it power. Lana Del Rey looks at the imagery we keep and tries to find what’s missing in it. What do we avoid looking at when we buy pictures of Marilyn Monroe, not thinking of why Norma Jeane Mortenson died so young? Whose stories do we allow to remain subdued? Ultraviolence rages to fill the vacancies behind the icons, to imagine the sorrow and desperation and flat-out anger of the women still cast in men’s spotlights.

A Clockwork Orange used the word “ultraviolence” to refer to gang beatings that lately seem to count as just regular violence. I’m not sure that’s what Del Rey is referring to here. She uses the word to sing about physical aggression, but the ultimate violence seems like it would be erasure, silencing, negation, the stuff you don’t hear about because it’s an absence by nature. You can see it if you read On the Road or listen to Berlin and try to imagine the inner lives of women who are mentioned in passing, who exist only to sculpt the stories of men.

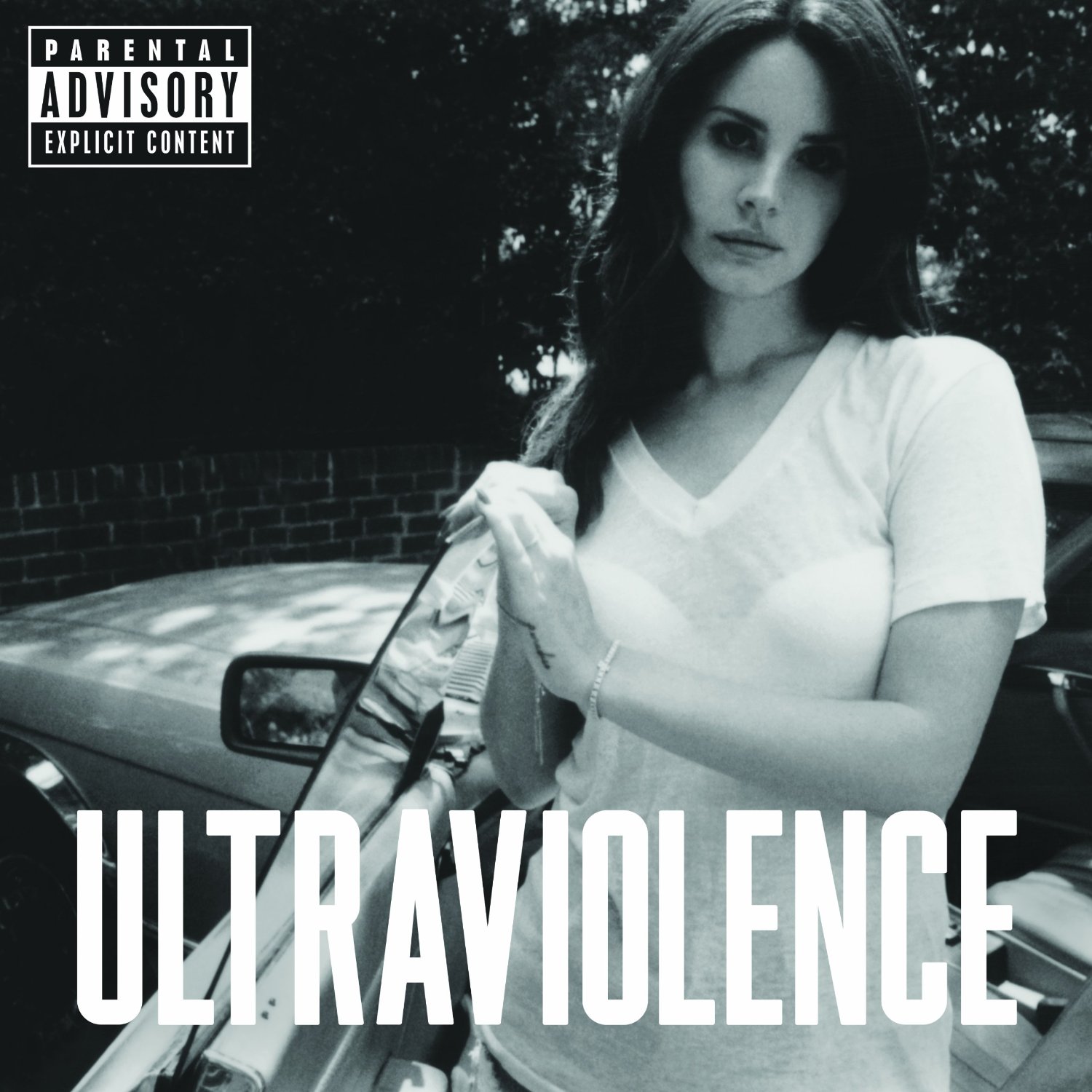

That negative space is its own kind of violence. Lana Del Rey steps into the shadows it leaves. She has power there, whispering old secrets, giving voice to characters who never got to speak for themselves. She counters a world in which “rape” is not even considered in the same category as “ultraviolence” by dragging up the second word and blaring it in capital letters below a photo of herself gazing enigmatically at the camera. She does her violence to the last century’s culture as we’ve rendered it in pixels the second time around. She is exactly the villain our history needs.

Essential Tracks: “West Coast”, “Money Power Glory”, and “Old Money”

More from Consequence of Sound: Stream Ultraviolence

More from Consequence of Sound: In dispute with indie labels, YouTube threatens to remove videos from Radiohead, Arctic Monkeys, and more

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com