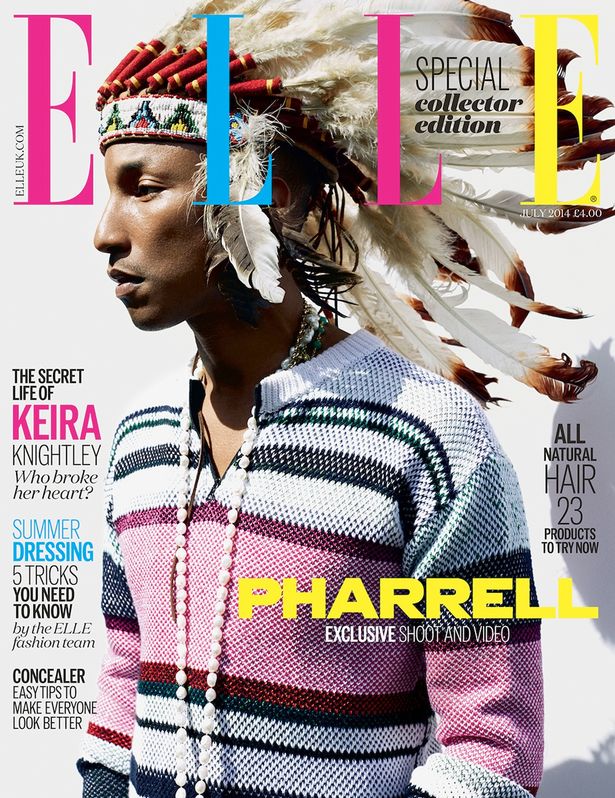

Pharrell’s feathers have been plucked by popular opinion, and he has bowed his head in apology. But the question raised by the singer’s unhappy appearance in a Native American headdress on the cover of Elle UK magazine remains: Where do we draw the line between cultural inspiration and cultural appropriation? And if cultural cross-dressing is a particularly dangerous game, especially in the era of the all-seeing Internet, why do stars and stylists alike continue to risk offense?

Fashion is notorious for ransacking the world’s closets in search of inspiration, but designers are no more culturally acquisitive than chefs who prepare fusion cuisine, musicians in search of a world beat, or any of us who pepper our conversations with foreign phrases in search of a certain conversational je ne sais quoi. The globe is a rich buffet, and those of us blessed with choice naturally go in search of cultural capital and varied experience.

The link between clothing and personal identity, however, means that putting on another culture’s clothes is a greater claim to ownership and belonging than sampling sushi or buying a burrito for lunch. As long as nudity isn’t a socially acceptable option, we are what we wear – and our desire to define ourselves through borrowed finery can either enrich or impoverish the source community.

Staying on the right side of the inspiration/appropriation divide requires individual awareness and attention to three S’s: significance (or sacredness), source and similarity. What’s the significance of the necklace you’re about to put on: is it just jewelry or a set of prayer beads? Did the source community invite you to wear that traditional robe, perhaps via voluntary sale, and does the community still suffer from a history of exploitation, discrimination or oppression? And how similar is that designer adaptation to the original: a head-to-toe copy, or just a nod in the direction of silhouette or pattern?

Two decades ago, French designer Jean Paul Gaultier’s Chic Rabbis collection, styled with Hasidic-inspired side curls or payot, raised a few eyebrows. His China and Spain collage and tartan-filled So British collections, however, were seen simply as inspired fashion. Years of tributes to country club culture and the American West by a boy from the Bronx, Ralph Lauren, are similarly uncontroversial. And when Moroccan-born, Israeli-raised Alber Elbaz sends a toga-inspired look down the Lanvin runway or Taiwanese-American Jason Wu creates an inaugural gown with vaguely similar historical roots for the First Lady, the descendants of Roman senators simply applaud.

On the other hand, Katy Perry’s performance in overly literal geisha garb recently drew criticism. But a year earlier, Prada’s far more transformative Japanese-inspired collection did not. Likewise, Valentino’s reimagining of an Indian sari as an Oscar gown for Jennifer Lopez was sufficiently distinct from its source to be a credit to both the designer and the wearer.

Pharrell’s error was to simply appropriate a traditional Native American headdress without either regard for its cultural significance or an attempt to turn some of its elements into something new. Had he worn a Philip Treacy millinery fantasy rendered in ostrich plumes or added a band of beading to a traditional fedora, the new style could have been a feather in his cap and an inspiration to fans instead of an embarrassing faux pas.

In the ideal case of transformative inspiration, both sides benefit. Who knows how long it would have taken for American women to don first bloomers, originally called “Turkish dress,” and then tailored trousers without the example of our pantaloon-clad sisters in the Middle East? On the source side, a community can profit economically from increased demand for its original designs and textiles, and culturally from a raised profile. Participation in a global society calls for cultural contribution, an identity tax that both identifies a distinct community and is a positive influence on the overall evolution of style – so long as it’s voluntary and doesn’t trample on the community’s values or cross legal lines.

Culture is fluid, and today’s taboo may be tomorrow’s trend. Still, civility requires at least an inquiry – unless, of course, you intend to offend. When Billionaires for Bush or Multi-Millionaires for Mitt go marching through the streets in tiaras and tuxedos, it’s a fair bet that they’re not concerned about offending the charity circuit set with their sartorial satire. Madonna’s wardrobe combination of a rosary, part of her own cultural heritage, and a belt reading “boy toy” on her debut tour, was a similarly deliberate transgression. But protest fashion and self-consciously sarcastic style are relatively rare.

By now, every design professional and dedicated follower of fashion is on notice that Native American headdresses are more than just a cool combination of feathers and beads. Successive apologies from Victoria’s Secret and model Karlie Kloss, Heidi Klum on behalf of Germany’s Next Top Model, and of course Pharrell and Elle UK, to name just a few, should have brought home the message that many Native American nations view these items as culturally significant and find ignorant attempts at homage to be harmful.

Cultural influences on fashion nevertheless have an important role to play – and our closets and our communities would be far emptier without them.

Susan Scafidi is a professor at Fordham Law School, founder of the nonprofit Fashion Law Institute, and the author of Who Owns Culture? Appropriation and Authenticity in American Law.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com