On March 6, 1770, a 34-year-old Boston lawyer, John Adams, agreed to a request that he represent a British captain and eight soldiers who had, the previous night, opened fire on a crowd of protesting civilians, killing five of them. The event became known to history as the Boston Massacre. Adams was told that no other lawyer would take the case. He suffered in the public eye and later said that it had cost him more than half of his law practice. But he was proud of his representation of the hated soldiers, calling it “one of the most gallant, generous, manly and disinterested actions of my whole life, and one of the best pieces of service I ever rendered my country.”

I am no John Adams — far from it. But I am an American lawyer who believes not only that even the most despised person — perhaps especially the most despised — has the right to a vigorous defense. Moreover, from of my experience as a civil rights and criminal defense lawyer, all too often the government’s charges against an accused will not stand up to serious scrutiny.

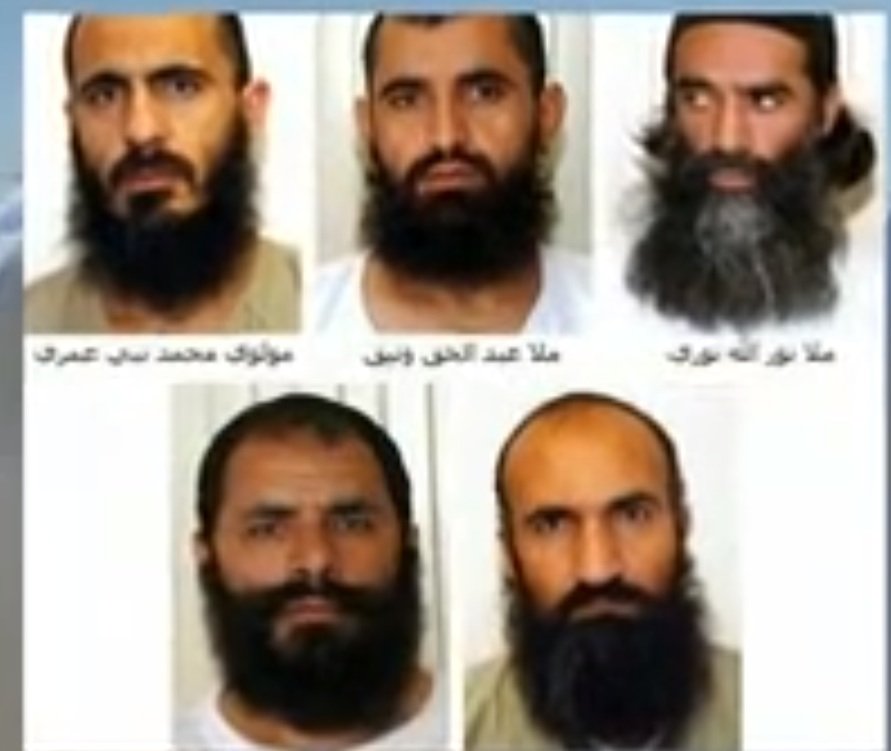

Together with two of my North Carolina colleagues, I have represented five Guantánamo detainees since 2007, including one of the Taliban prisoners recently transferred to Qatar in exchange for the release of Sergeant Bowe Bergdahl. I agreed to represent them on a pro bono basis because of my conviction that if lawyers do not step forward to challenge government overreaching, who will? What I have learned demonstrates that careful examination of the evidence will puncture the exaggerated and hysterical claims of politicians and pundits.

Such is the case with the men detained at the U.S. Naval Base at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. Altogether, some 779 Muslim men from 43 different countries, whose ages have ranged from 13 to 90, were brought, hooded and shackled on clandestine flights, to Gitmo (as the base is informally called) to be kept in isolation from family, friends and — had the government had its way — from lawyers. Bush Administration leaders claimed that they had been “picked up on the battlefield fighting American forces,” were “the worst of the worst,” “bombmakers,” “terrorists,” “among the most dangerous, best-trained, vicious killers on the face of the earth,” “associated with Al-Qaeda.”

Yet that Administration, quietly and without court compulsion, released well over 500 of them, and the Obama Administration, which inherited 242 detainees, has released others, according to a report from Seton Hall. Some men have died during their prolonged custody — and some of those by their own hand. As it turns out from the publically available facts, the overwhelming majority were not who our government claimed they were. U.S. forces captured only 5% of them. Others were bought from tribesmen motivated by the large American bounties. Eighty-six percent were arrested by the Northern Alliance or Pakistani authorities, having been captured for reasons that are, to say the least, opaque. Some were seized from their homes, places of work, or simply off the street, mostly in Pakistan, not Afghanistan, often based upon anonymous allegations of a connection to Al-Qaeda or the Taliban. Most were never on a battlefield and had not been determined to have committed any hostile act at all against the U.S. or its allies. The government officials and politicians simply misstated the facts.

John Adams knew the importance of focusing on the facts, not on labels. He told the Boston jury this: “Facts are stubborn things, and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictums of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.” That jury examined the facts, and it acquitted the British captain and six of his eight soldiers, convicting the other two only of manslaughter.

In the cases of the Guantánamo detainees, we lawyers cannot discuss the specific facts publicly, because we were required to trade our free speech for access to the classified evidence necessary to represent our clients. But it is telling that after over a dozen years of detention, the government has managed to charge, try and convict only a handful — fewer than 10 — of the 779 men it brought to the base. Five were convicted of minor charges (some that were not even crimes at the time of their detention) and have been released. One of the convictions was overturned on appeal; other appeals remain pending. This is not a record of ringing prosecutorial success. Of the five men I represented, including the Taliban political official just sent to Qatar, none were ever charged with even the most minor crime; they were simply held for years without charges until it pleased the government to send them back. Where is the evidence that they are terrorists? About half of the 149 men still left at Guantánamo have long been determined not to be a threat and have been approved for transfer; the only impediments to their release are political.

In his closing speech to that Boston jury, John Adams quoted these lines from the Italian penologist, Cesare, Marchese di Beccaria:

If, by supporting the rights of mankind, and of invincible truth, I shall contribute to save from the agonies of death one unfortunate victim of tyranny, or of ignorance, equally fatal, his blessings and years of transport will be sufficient consolation to me for the contempt of all mankind.

Contesting the basis for our country’s indefinite detention of these men has been costly and challenging, but professionally fulfilling. Certain episodes in our history — the internment of Japanese-American citizens during World War II comes to mind — are now regarded in hindsight as tragic aberrations from American values. At such times it is the duty of lawyers to step forward and hold the nation accountable to its ideals.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com