You are getting a free preview of a TIME Magazine article from our archive. Many of our articles are reserved for subscribers only. Want access to more subscriber-only content, click here to subscribe.

“If he were not the greatest President, he was the best Actor of the Presidency we have ever had.” –John Adams, on George Washington

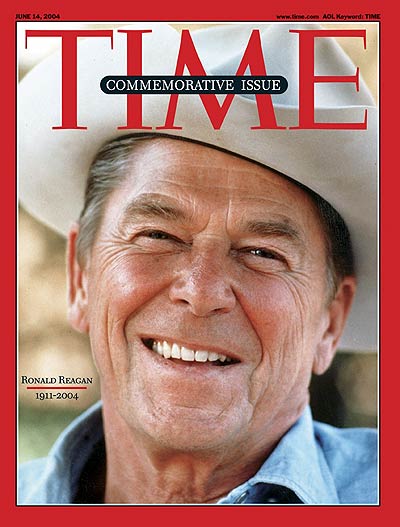

America’s Presidents tend to die young. Maybe it is in the nature of the men who reach such heights, or of the job once they attain it. But only John Adams and Herbert Hoover lived past 90; Ronald Reagan was the third, and perhaps the only one to achieve the goal of dying young as late as possible. When he passed away last week at age 93, he had long been gone from the public stage; but that meant that people remembered him as he had always been, a man of easy grace and endless hope, whose hair would never turn gray; a man who, the first time he walked into the Oval Office as President on the day of his first Inaugural, got goose bumps and wasn’t ashamed to say so.

Hope is an infectious disease, and Reagan was a carrier. The country he courted and finally won over in 1980 was a dispirited place, humiliated abroad, uncertain at home, with a hunger for heroes but little faith that they could make any difference. But you can, he told us. I am not the hero, you are. “Let us renew our faith and our hope,” he declared in his first Inaugural Address. “We have every right to dream heroic dreams.” And he would serve as Dreamer in Chief. “What I’d really like to do,” he said after six months in the White House, “is go down in history as the President who made Americans believe in themselves again.”

In the process, he made them believe in the presidency as well. After the 1960s and ’70s, there were real doubts about whether a mortal man could handle the country’s highest office. It had destroyed Johnson, corrupted Nixon and overwhelmed Ford and Carter. Reagan restored the belief that an ordinary American raised in the heartland could lead the country and give it a sense of direction and purpose. At a time when the country had been captivated by youth culture for more than a decade, voters chose a President who was nearly 70 when he took office, a kind of living time capsule of the American Century, born before the phrase world war had been introduced, a child when the Russian Revolution gave birth to the empire whose defeat he would accomplish as President. Somehow it took America’s oldest President to make the country feel young again, its mission not yet completed, its glory days ahead.

Even if it wasn’t always morning in America during the years of his presidency, Reagan’s eagerness to insist that it was tapped into a longing among voters. They didn’t want to picture themselves turning down their thermostats and buttoning up their cardigans. They wanted to strut again. Reagan opened his arms and said, Walk this way. And when the country had to mourn, he led it in grieving that was eloquent yet unbowed, as in 1986, when he postponed his State of the Union address to speak of the Challenger disaster. “We will never forget them,” he said of the shuttle’s crew, “nor the last time we saw them, this morning, as they prepared for their journey and waved goodbye and slipped the surly bonds of earth to touch the face of God.”

He replaced a President who had talked of America’s malaise and proceeded to speak of its destiny and greatness, notions that had been dismissed as naive or arrogant. Talk of America as a shining city on a hill was long out of fashion, but it was a core belief of Reagan’s, and it is no accident that it animates the man who occupies the White House now. George W. Bush, though a President’s son, is cast as Reagan’s heir even more than his father’s. Long after Reagan had retreated from the public eye behind the veil of Alzheimer’s disease, his influence over the politicians of our time, from both major parties, only grew. “The question really arose whether the presidency was a viable institution,” says Fred Greenstein, a presidential scholar at Princeton. “With Reagan, that changed. He reminded us what a confident and sure President looked like.”

For a man with the power to pull history around a corner; to end a long, cold, fearsome war; to change the conversation of our politics and culture as much by the sheer force of his personality as by the power of his ideas, Ronald Reagan was an unaccountably modest and good-natured soul. He seemed untouched by the arrogance and self-regard common to actors and politicians, to the point that when a brash reporter asked him on the eve of his election what he thought the American people saw in him, Reagan said, “Would you laugh if I told you that I think, maybe, they see themselves, and that I’m one of them?”

He wasn’t, of course. This was the actor’s gift, to be both larger than life and disarming at the same time. He was, in fact, never so simple as he seemed. A fervent tax cutter, he raised taxes significantly four times as economic conditions and reform demanded. The man who said government was not the solution, it was the problem, actually presided over its continued expansion. Far from abolishing the departments of Energy and Education, he added a new Cabinet-level department, for Veterans Affairs. The archconservative who was skeptical of Social Security ultimately was credited with saving it. He came into office looking not to survive the cold war but to win it, building up America’s defenses to confront the “evil empire” but then backing off enough to give Mikhail Gorbachev room to change course. Reagan may have been the champion of missile defense, but he also declared as his dream the complete abolition of nuclear weapons, a position that made even the moderates around him flinch.

He was, in other words, that most uncommon politician, a man of clear conviction who was capable of compromise where necessary and growth where possible, whose ideas were both deeply held and able to evolve as circumstances changed or expediency required. Likewise, the man himself was not so simple, not to mention simpleminded, as his critics held–the “kindly fanatic” in Garry Wills’ phrase. He confounded his biographer Edmund Morris, remained opaque even to friends of many years. The notion that he was a second-rate actor who did well with a script continues to be dispelled with the release of his radio addresses and more recently, his personal letters, which show a far more subtle mind and sophisticated outlook than the caricature ever suggested. But then, Reagan had a gift for being underestimated, which served him well in all the lives he led.

“I loved three things: drama, politics and sports, and I’m not sure they always come in that order,” Reagan once said. His picture in the high school yearbook bore the caption “Life is just one grand sweet song, so start the music.” He was born on Feb. 6, 1911, in Tampico, Ill., in that Midwestern heartland that is thought to be the seedbed of national heroes. But nothing about his origins augured any remarkable success. His father Jack, who had never reached high school, was a shoe salesman and an alcoholic. The family moved often; money was short. Reagan was 11 when he came home one day and found his father lying dead drunk on the porch. “I wanted to … pretend he wasn’t there,” Reagan recalled. “I bent over him, smelling the sharp odor of whiskey … I got a fistful of his overcoat [and] managed to drag him inside and get him to bed.”

Sports gave Reagan a chance to get an education. He won a scholarship that paid half his $180 annual tuition at tiny Eureka College; he washed dishes to pay for his meals. Reagan had hardly arrived when the college’s new president tried to cut back the faculty, so Reagan helped organize a student strike. In the process he developed his taste for audiences and his talent for oratory. “I discovered that night that an audience had a feel to it,” he said of this first speech, “[and] that audience and I were together. When I came to actually presenting the motion … there was no need for parliamentary procedure. They came to their feet with a roar … It was heady wine.”

Reagan also discovered that he was an actor. Taken to see a touring antiwar play, Journey’s End, he identified strongly with the hero, even began to feel that he was the hero. “Nature was trying to tell me something,” he recalled later, “namely that my heart is a ham loaf.” He spent much of his time thereafter in student theatricals as well as football and swimming, with only the minimum study necessary to major in economics. Dutch Reagan (his father had bestowed the nickname at birth) emerged into the Depression-stricken America of 1932 and found there were very few jobs for actors and fewer still for football players. He borrowed the family Oldsmobile and wandered through nearby towns, looking for work at local radio stations. A station manager in Davenport, Iowa, asked him to narrate an imaginary football contest, and Reagan poured into the fakery all the enthusiasm of desperation. He was hired for $5 a game.

By 1937 he had gone no farther than Des Moines, which is a long way from Hollywood, but he persuaded radio station WHO to send him to California to cover the spring training of the Chicago Cubs. A Des Moines friend who was working as a singer sent him to see her agent, who called the casting director at Warner Bros. and said, “I have another Robert Taylor sitting in my office.” Warner gave him a screen test, then signed him for $200 a week.

Reagan’s early films, as many as nine a year, were forgettable. But there was one part that he yearned to play. He wanted somebody to film the life of Notre Dame’s great football coach Knute Rockne so that he could play Rockne’s star halfback, George Gipp. Reagan proselytized so fervently that someone filched the idea. Warner announced it would make the Rockne story, but the announcement made no mention of Reagan. He went to see the producer, asked for the part of Gipp and was told he was too small.

“But I played football for eight years,” Reagan protested. “Gipp weighed five pounds less than I weigh right now.” The producer was still dubious. The problem, Reagan saw, was that he was wearing a business suit, and the producer envisioned a behemoth in helmet and shoulder pads. Reagan raced home, gathered up some pictures of himself in uniform, raced back to the studio and won the part. It made him famous, and years after he performed Gipp’s death scene, he would still get “a lump in my throat … just thinking about it.”

The same year he played Gipp, he married actress Jane Wyman. Warner assigned him to Kings Row. Playing a small-town lothario named Drake McHugh, he seduces the daughter of the town surgeon, who takes revenge by amputating both of the youth’s legs. The horrible moment of self-discovery made a deep impression on Reagan. The day the scene was shot he clambered onto the sickbed, which had a hole cut in the mattress to hide his legs. “I spent almost that whole hour in stiff confinement,” Reagan said. “Gradually the affair began to terrify me. In some weird way, I felt something horrible had happened to my body.” When shooting began, Reagan recalled, “I opened my eyes dazedly, looked around, slowly let my gaze travel downward … I can’t describe even now my feeling as I tried to reach for where my legs should be. ‘Randy!’ I screamed. Ann Sheridan–bless her–playing Randy, burst through the door.” Then Reagan cried out the question that he was later to make the title of his first autobiography: “Where’s the rest of me?”

Kings Row made Reagan a star. But it was 1942, and Pearl Harbor had brought the U.S. to its inevitable involvement in World War II. Reagan could see very little without eyeglasses, but he had bluffed his way into the cavalry reserve back in Des Moines because it gave him a chance to go riding. Called up by the Army, he was examined by a doctor who concluded, “If we sent you overseas you’d shoot a general.” Another added, “Yes, and you’d miss him.” Barred from combat, Reagan spent the war years making training films at “Fort Roach,” the old Hal Roach Studios, just six miles from Hollywood.

What occupied Reagan in the postwar years was Hollywood union politics. “I was a near hopeless hemophilic liberal,” Reagan said later. “I bled for causes. I had voted Democratic, following my father, in every election. I had followed F.D.R. blindly … ” By 1947 he was president of the Screen Actors Guild and found himself embroiled in the union wars ravaging Hollywood. Reagan came to believe that the bitter strikes in 1945 and 1946 by stagehands of the Conference of Studio Unions represented a communist attempt to take over Hollywood, and that belief changed his political views forever. In the subsequent era of the blacklists, Reagan not only cooperated in the purging of suspected communists but also served as an undercover FBI informant. Speaking to TIME’s Laurence Barrett three decades later about his recollection of the leftists’ tactics, he said with unusual bitterness, “I discovered it firsthand–the cynicism, the brutality, the complete lack of morality in their positions, and the cold-bloodedness of their attempt, at any cost, to gain control of that industry.”

Reagan felt with some justification that his union activity damaged his career as an actor. After more than 50 films, he was getting no offers of good parts. By 1953 he was reduced to doing a nightclub routine in Las Vegas, where he introduced various singers and dancers and made apologetic jokes about his own inability to either sing or dance. Was the optimist discouraged? Hardly. He was soon offered a new job that was to change his whole life. For $125,000 a year, he would act as host and occasional star of a weekly television drama series for General Electric; for 10 weeks each year he would also act as a kind of goodwill ambassador to GE plants around the nation.

As one of the first prominent Hollywood actors to defect to the much scorned new medium of TV, Reagan revived his acting career. The General Electric Theater, with Reagan as host from 1954 to 1962, dominated the Sunday-night ratings. But what changed Reagan was his tours of the GE plants. Later, Reagan’s opponents often underestimated him, dismissing him as “just an actor,” an amateur lacking political experience. What they failed to see was that although Reagan had not spent much time in conventional politics, he had gained both skill and experience in what was to become the politics of the TV age, the politics of electronic images and symbols. Reagan once figured that in his eight years at GE, he had visited every one of the company’s 139 plants, met more than 250,000 employees, spent 4,000 hours talking to them and “enjoyed every whizzing minute of it.” He polished his delivery, the intimate confiding tone, the air of sincerity, the wry chuckle, the well-timed burst of fervor.

Reagan also listened. As he zigzagged across the country, he acquired a powerful sense of what ordinary people thought and hoped and wanted. “That did much to shape my ideas,” Reagan said later. “These employees I was meeting were a cross section of America, and damn it, too many of our political leaders, our labor leaders, and certainly a lot of geniuses … on Madison Avenue, have underestimated them. They want the truth, they are friendly and helpful, intelligent and alert. They are concerned … with their very firm personal liberties. And they are moral.” The hemophilic liberal was becoming steadily more conservative. Over the years he devised a series of slogans that many experts considered simplistic but many voters seemed to respond to. “Government is not the solution to our problem. Government is the problem,” Reagan would say, over and over. “Government causes inflation, and government can make it go away. The best social program is a job.”

He eventually became so vocally critical of such sanctified New Deal creations as Social Security and the Tennessee Valley Authority that GE abruptly dropped him in 1962, but Reagan was by now much in demand on what he liked to call “the mashed-potato circuit.” When the conservatives rallied behind the presidential campaign of Senator Barry Goldwater in 1964, Reagan’s gift for oratory provided one of the unexpected highlights in the doomed campaign. “You and I have a rendezvous with destiny,” Reagan declared (borrowing one of Franklin Roosevelt’s most famous lines) to a G.O.P. fund-raising dinner in Los Angeles. “We will preserve for our children this, the last best hope of man on earth, or we will sentence them to take the first step into a thousand years of darkness.”

When Goldwater’s campaign ended in disaster, Reagan’s rhetoric still echoed in the mind of a prosperous Los Angeles Ford dealer named Holmes P. Tuttle. He invited to his home a group of wealthy California conservatives, and they decided that Reagan should be their gubernatorial candidate in 1966. Governor Pat Brown was an amiably conventional liberal, who ran on his amiably conventional record. Reagan spotted and exploited a new issue: middle-class discontent over disturbances at the University of California and over the disturbances of the 1960s in general. He vowed to “clean up the mess at Berkeley.” He won by a margin of almost 1 million votes out of 6.5 million.

Reagan proved a surprisingly pragmatic and successful Governor. Though all his campaign rhetoric opposed tax increases, he soon found that he needed more revenue to do all he wanted to do, so he imposed the biggest tax hike in state history. Winning a second term by half a million votes, Reagan turned to simplifying and reducing welfare spending and got his way by shrewd bargaining with his Democratic opposition. But his successes came during the years when his party was falling into disgrace nationally because of President Nixon’s Watergate scandal. When Reagan retired as Governor in 1975, according to one poll, fewer than 20% of Americans considered themselves Republicans.

Yet to Reagan the optimist, it was just a matter of patience and marketing. “I believe the Republican Party represents basically the thinking of the people of this country, if we can get that message across to the people,” he said. “I am going to try to do that.” He began a weekly commentary broadcast on some 200 radio stations and a biweekly column in 175 newspapers. Those efforts, together with his popularity on the mashed-potato circuit, increased his income from a Governor’s salary of $49,100 to about $800,000 a year.

He was irked, though, to see Republican leadership after Nixon’s resignation fall into the hands of Gerald Ford, who did not represent right-thinking conservatism. It was almost unheard of to challenge an incumbent President from one’s own party, but in 1976 Reagan took the risk, losing at the convention, 1,187 delegates to 1,070. When Ford went down to defeat, Reagan was well positioned to claim the right to be the next challenger to President Jimmy Carter in 1980.

Except that he was old. By Inauguration Day 1981, he would be almost 70, older than any man had been when beginning his presidency. Reagan countered with a joke: “Middle age is when you’re faced with two temptations, and you choose the one that will get you home at 9 o’clock.” Campaign manager John Sears, the Washington lawyer and strategist who had helped Reagan nearly unseat Ford in 1976, believed Reagan should remain aloofly “presidential.” The principal result was that he lost the first big contest, the Iowa caucuses, to hard-driving George Bush. With the whole campaign at stake in the upcoming New Hampshire primary, Reagan shifted to the grittier strategy known among aides as “letting Reagan be Reagan.” That led to one of the most memorable scenes of the year: the debate in Nashua, at which Bush sat out a procedural argument in frozen silence while someone tried to turn off Reagan’s microphone, and Reagan angrily cried out, “I am paying for this microphone!” It also led to a sweeping victory that virtually assured him the nomination.

Carter too was confident that Reagan would be no match. Reagan being Reagan again upset the prognostications. While aides tried to stuff him with facts for his important TV debate against Carter, the challenger practiced one-liners, notably one that he flung at Carter with considerable effect: “There you go again!” Even more stinging was his repeated question to the voters, “Are you better off than you were four years ago?” The answer was, 50.7% of the votes for Reagan, with 41% for Carter and 6.6% for independent John Anderson. The electoral votes were even more lopsided: 489 for Reagan, 49 for Carter.

Reagan took the vote as a mandate for an “era of national renewal” that he proposed to achieve by some unfamiliar methods: tax cuts, budget cuts, less regulation, less welfare. But before he could even begin to achieve anything like that, he had to endure the shattering attack by John Hinckley, a reasonably prosperous and reasonably well-educated young man whose only motive for murder was his desire to impress a movie actress whom he had never met, Jodie Foster. It was Reagan’s luck that five of the six bullets missed him, but one apparently ricocheted off his car, spun below his armpit and punctured a lung. Reagan did not even know he was wounded until he began tasting his own blood as the armored limousine sped him away from the scene. But he was brave, stoic, uncomplaining. Lying in bed, he even began offering a stream of jokes. To doctors as he entered surgery: “Please tell me you’re Republicans.” On coming out of anesthesia, he paraphrased W.C. Fields: “All in all, I’d rather be in Philadelphia.” And again: “If I had this much attention in Hollywood, I would have stayed.”

Long after Reagan was restored to health, the effects of the attack lingered. “There was a certain sadness,” said one of his old friends, former Senator Paul Laxalt. “You could see it in his eyes. It wasn’t just the physical pain. I think that he was deeply hurt, emotionally, that this could happen to him.” Reagan was reluctant to admit any such hurt, but he did acknowledge to an interviewer that it had been a “reminder of mortality and the importance of time.” Beyond that, he liked to say, “God has a plan for everyone.”

Reagan had his own plan. When he asked the voters whether they were better off than they had been four years earlier, he was aiming at a continuing phenomenon known as stagflation, an inflation that had climbed to 13.5% in Carter’s last year while the economy remained stagnant. The new Congress gave the new President what he most wanted, a 25% tax cut over three years and a $35 billion cut in the budget. At a time when many economists were arguing that America would just have to learn to live with 10% inflation annually, Reagan reappointed inflation fighter Paul Volcker as chairman of the Federal Reserve and supported his war on inflation despite withering attacks and considerable domestic pain. The economy swooned into a recession: by the following year, the GNP was shrinking at a rate of 1.9%. Unemployment reached 10.8%, the highest since the Depression, and the poverty rate grew faster than it had in decades. By 1983 the annual federal budget deficit had climbed past the $200 billion mark.

Reagan and the supply-side theorists around him were so convinced of the virtues of growth that they were less concerned with getting around to the spending cuts and worrying about deficits. Some congressional leaders and White House aides cooperated in urging Reagan to return to conventional measures, some “revenue enhancements,” but the President rejected all evidence of worse troubles ahead. Everything would soon get better, he kept saying. And to the surprise of most professional economists, just about everything did.

By 1984, in good time for his re-election campaign, the GNP was growing a robust 6.8%, while inflation had dropped to 4.3%. And from then on, despite the spectacular but brief stock-market crash in 1987, the boom kept right on booming. Those gains, however, were unequally distributed. Reagan liked to say that the government provided a “safety net” for the “truly needy,” but it was during these years that, for the first time since the Depression, there appeared those huddled figures who became known as “the homeless.”

Another pillar of Reagan’s approach was to get government out of the way of growing businesses. Deregulation had started tentatively under Carter with the airlines, but Reagan applied it broadly, to energy and broadcasting and butressed it with a dismantling of antitrust laws. Reagan was a staunch free-trader and did little to stop the onslaught against sluggish American corporations from aggressive Japanese manufacturers. Reagan’s term coincided with the height of Japan’s economic boom, and his instinct was that in the long run, it would be better to let most companies fend for themselves.

Under pressure from foreign competition, and with the antitrust lawyers looking the other way, Wall Street tumbled into a fever of mergers, leveraged buyouts, massive restructurings and corporate raids. It was painful, it was chaotic, it hurt a lot of workers, both blue and white collar. But in the end it seems to have produced a more competitive economy, with companies more nimble, more responsive to customers and more innovative, even if their workers felt less secure or loyal. The 1980s shakeout helped prime the economy for its leap into the high-productivity, technology-fueled boom of the next decade.

A philosophical offshoot of Reagan’s impulse to deregulate was the 1986 tax-reform bill. Although the primary goal was to lower tax rates a lot, to encourage work and investment, the trick was to pay for it by eliminating most of the exemptions and special tax breaks and shelters, all the ways the government tried to micromanage the economy and control behavior. Reagan and the reformers believed in letting individuals make decisions based on their own view of economic self-interest, not the tax code’s. By the end of Reagan’s term, the ground had shifted to the point that it became all but impossible for politicians to propose big new spending programs in the face of so much red ink. “Reagan’s policies,” said Stanford economist Michael Boskin, “were all designed to do what public policy could do to transform a badly ailing economy into a highly competitive one.”

During his campaign for the White House, Reagan asked the voters not only whether they were better off but also whether the nation was stronger than it had been four years earlier. And there was little doubt about the answer. At the time, America’s diplomats were being held hostage in Iran, a rescue attempt had crashed in flames in the desert, and the Army–by its generals’ own admission–was going “hollow.” Though Presidents Nixon, Ford and Carter had all promoted the development of new weapons systems–the MX missile, F-117 fighter, the B-2 bomber, the M1 tank–it was under Reagan that those programs bore fruit, along with a mighty, imaginary weapon born all of Reagan’s own instincts.

When Reagan took office, the Soviet Union was 64 years old, nearly eligible, as it were, for Social Security. The rot in its marrow, while still hidden to the outside world and U.S. intelligence, was metastasizing. Reagan’s great contribution to the end of the cold war was first understanding that Moscow’s cancer was terminal and then working to ensure–through arms control, constrained rhetoric and personal diplomacy–that the end would come about, peacefully but inexorably.

Reagan’s instincts, like his rhetoric, evolved over the course of his two terms as the ground began shifting beneath him. After a decade of Presidents carefully talking detente, Reagan denounced the Soviet Union as the “evil empire” and accused its leaders of claiming “the right to commit any crime, to lie, to cheat.” To armor such rhetoric, Reagan demanded and got a huge increase in U.S. defense spending. He nearly doubled defense spending during his first term while deploying medium-range nuclear missiles in Europe and battling communists in Central America. He rarely gave ground, and fumbles in foreign policy–like the deaths of 241 Marines on an ill-advised mission to Lebanon in 1983–were eclipsed by sending the troops into Grenada only days later.

In March 1983, Reagan gave a landmark speech calling on the U.S. to build a shield that would render Moscow’s nuclear missiles “impotent and obsolete.” Whether or not the U.S. could build such a Star Wars shield was less important than the Soviets’ knowledge that they themselves never could. The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) quickly became an obsession of the Soviet leadership. Konstantin Chernenko and Mikhail Gorbachev tried to derail it through propaganda and arms control. But Reagan steadfastly refused to give it up.

Reagan’s boosters argue that it took a weapon that never worked to win a war that was never fought. For having failed to kill the program, the Soviets were prodded by SDI into trying to modernize their society–which could only be achieved by liberalization. “I used to think SDI didn’t have a great impact,” says Lawrence Korb, who was an Assistant Secretary of Defense during the Reagan Administration. “But as I meet former Soviet marshals and talk to them, I’m increasingly convinced it had a major impact. The Soviets feared it could work, and that had a tremendous impact, psychologically, on them.”

For all Reagan’s foreign policy successes, his final years were overshadowed by scandal. He had become committed to finding a way to free American hostages held in Lebanon. In 1985 his National Security Adviser, Robert (Bud) McFarlane, oversaw a scheme in which Israel, as a stand-in for the U.S., would provide TOW antitank missiles to an Iranian arms dealer in exchange for help in obtaining the release of hostages. Did Reagan, who had repeatedly declared he would make no deals with Iran or terrorists, agree to this one? McFarlane later testified that he did. Reagan said he couldn’t remember. After a shipment of missiles (and one hostage released), the Iranians demanded more. Prompted by CIA Director William Casey and by McFarlane’s successor, John Poindexter, Reagan signed a “finding” that this otherwise illegal deal was necessary for national security, but he did not inform Congress, as required by law.

After several more arms shipments, another hostage was released. By this time, Poindexter had delegated much of the maneuvering to his gung-ho assistant, Marine Lieut. Colonel Oliver North, who was also cooperating with the CIA in supplying arms to the Nicaraguan rebels, even though Congress had formally forbidden any such action. Somehow there emerged what North later called a “neat idea”–using money that the Iranians paid for illegal arms to buy more illegal arms for the Nicaraguan rebels.

When all this official smuggling and dissembling came to light shortly after the summer of 1986, it was a cruelly self-inflicted wound to the whole Reagan Administration. North was fired; Poindexter resigned. McFarlane, after attempting suicide, pleaded guilty to charges of withholding information from Congress. On the eve of his scheduled appearance before a Senate investigative committee, CIA Chief Casey suffered a seizure and was rushed to the hospital; he died five months later. But politically, the chief victim was Reagan, who kept saying he had broken no laws and negotiated with no terrorists. Polls showed that most Americans didn’t believe him.

At the height of the Iran-contra scandal, there was some anxiety in the White House that Reagan might actually be impeached, and yet many Americans seemed to forgive him as easily as he forgave himself. When he left office just a year later, his approval rating with the public stood at 63%.

If anything, the public’s admiration for him grew in the years after he left office–not least because of a fervent effort on the part of his admirers to exalt him. His disciples, having already lobbied for Washington’s airport and a major office building and aircraft carrier to be named for him, are at work having a public building in his honor in all U.S. counties, and perhaps his face on the $10 bill. Popular affection and admiration ultimately mixed with sympathy once he revealed his battle with Alzheimer’s in 1994. “At the moment I feel just fine,” he wrote in a letter revealing his condition. “I intend to live the remainder of the years God gives me on this Earth doing the things I have always done. I will continue to share life’s journey with my beloved Nancy and my family … When the Lord calls me home, whenever that day may be, I will leave with the greatest love for this country of ours, and eternal optimism for its future.”

That journey would last another decade, in which Nancy was fierce in her protection of his privacy and dignity. Hers was said to be the last face he recognized. The excellent health that had served him well through his life had the effect of prolonging his death: a mind fading while a body pushed on, full of energy and health it no longer needed. He would rake the leaves out of the pool for hours, Morris wrote, not knowing that his Secret Service agents would quietly replace them. Had he been a less vigorous man, the doctors said, he would have died much sooner.

What history will finally make of Ronald Reagan remains, for the time being, history’s secret. Surveys have found him ranked high on lists of both the most underrated and overrated Presidents, and yet in recent years there had come a reconsideration of the man and his legacy.

To his supporters, particularly those who called themselves conservatives, Reagan’s triumphs represented an enduring revolution in American politics, an end to the New Deal and its heritage of ever growing government power, regulation, taxing and spending. “We were all revolutionaries, and the revolution has been a success,” Reagan said on leaving office.

Throughout virtually his whole life, Reagan seemed to cling to an unchanging vision of an America that the Hollywood of his youth tried both to express and create. It was a Norman Rockwell vision of elm-shaded village life, of freckle-faced boys going fishing, of parading on July 4; it was a Horatio Alger vision of hard work and thrift and virtue rewarded. If the Gipper died young, he nonetheless died a hero. That was the America in which Reagan wanted Americans to believe, and in which many Americans themselves wanted to believe. And to a surprising extent, they succeeded.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com