This past summer, Tennessee state Rep. Sheila Butt got a call from a mother who said she wanted to talk about her son, a junior in high school. The woman explained that her son’s history teacher was writing homework assignments on the board in cursive—and her son couldn’t read them. Butt did some digging and found similar problems across the state. “We had students not able to read, nor write their signature, in cursive writing … That was unbelievable to me,” she said in February. “To say that we’ve educated children in Tennessee and taken away this form of instruction, this link to our heritage out of classrooms, is a grave disservice.”

Butt, speaking at a committee hearing, had just introduced an amendment that would mandate cursive instruction in all public schools, a measure that was put on the books as law in mid-May. At least five other states have considered—or are still considering—similar bills this year, all attempts to defy the oft-heralded “death of handwriting” wrought by the almighty keyboard. But proponents say they aren’t just nostalgic Luddites. Here are other arguments the pro-cursive crowd uses to demand classroom time alongside QWERTY.

American institutions still require signatures for things!

Butt provided the example of needing to both sign and print one’s name to receive a registered letter at the post office, as well signing one’s name to support a candidate for public office. More generally, one’s John Hancock is a tool that can provide security; experts have said that printed letters are easier to forge.

It’s good for our minds!

Research suggests that printing letters and writing in cursive activate different parts of the brain. Learning cursive is good for children’s fine motor skills, and writing in longhand generally helps students retain more information and generate more ideas. Studies have also shown that kids who learn cursive rather than simply manuscript writing score better on reading and spelling tests, perhaps because the linked-up cursive forces writers to think of words as wholes instead of parts.

Kids can’t read the Declaration of Independence!

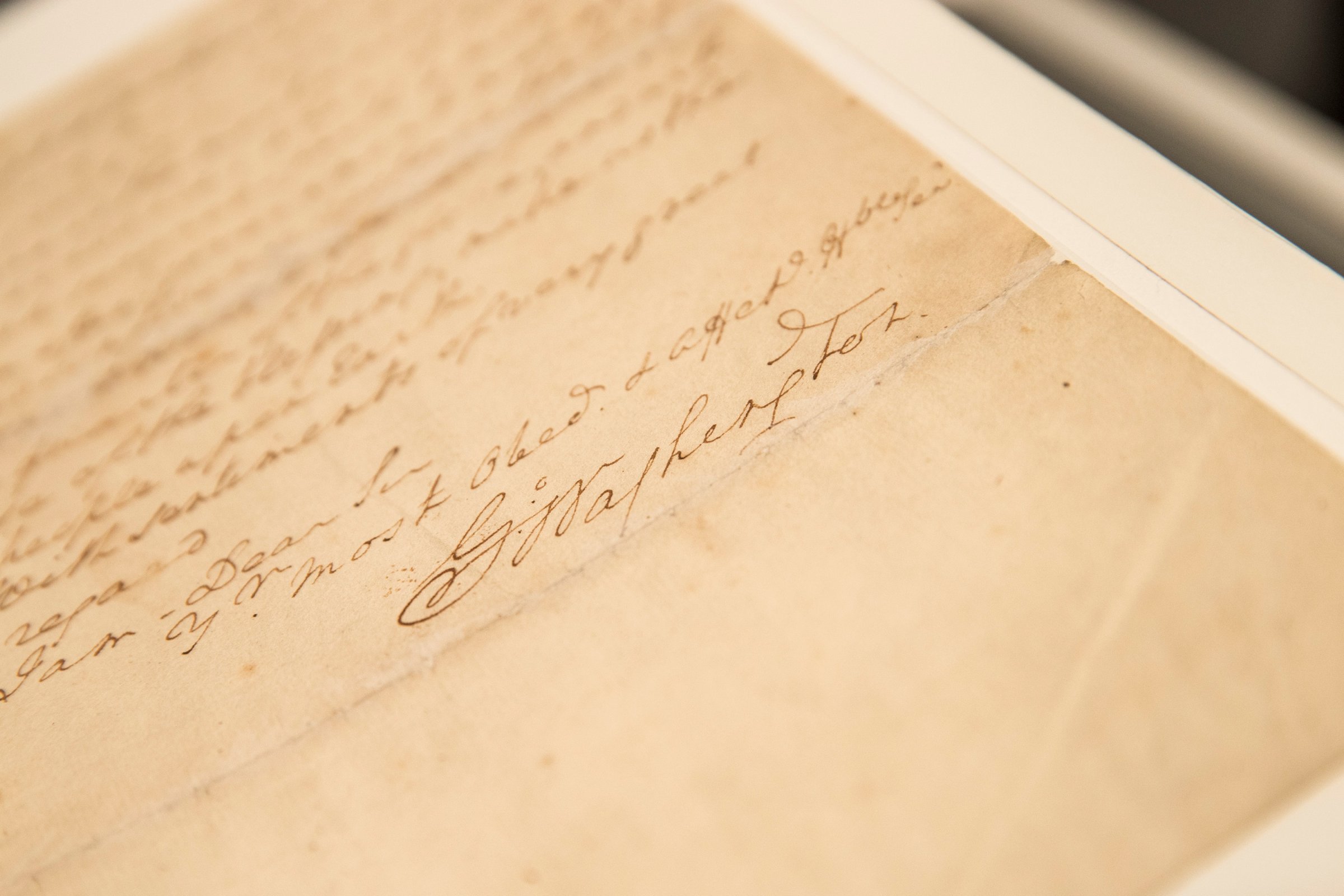

At least not the original, pen and ink version. Butt waxed about the thrill of reading the Emancipation Proclamation or the Bill of Rights in their founding forms—and what a travesty it is to raise Americans who would look at those documents as if they were written in hieroglyphics. “So that students are able to read our most valued historical documents in their original form,” reads a New Jersey proposal, “this bill requires that cursive be included in the public school curriculum.”

Some people need it!

As Maria Konnikova outlines in this New York Times piece, some people suffer brain injuries that damage their ability to write and understand print—while their ability to comprehend cursive remains. Researchers have also, she notes, suggested that cursive can serve as a teaching aid for children with learning impairments like dyslexia.

People like the way it looks!

Though this is presented sans science, one assumes love letters are generally more effective when they look like this than when they look like this. More concrete proof of cursive’s aesthetic prowess can be found in established arts like cursive calligraphy. In a 1950 TIME story about a calligraphy competition between the English schoolboys of Eton and Harrow, the columnist reaches this conclusion: “More important than the judges’ verdict was the evidence that the Commonwealth’s future leaders would continue to write a clear and handsome hand.”

Of course, there at least as many arguments to recommend typing, central as it is to success and communication in our daily lives. But the legislation that keeps on coming is proof that there’s still plenty of will to keep kids in the loop.

This is an edition of Wednesday Words, a weekly feature on language. For the previous post, click here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com