Correction appended, May 30

There are lots of ways to quit being taken seriously in America. You can deny climate change; you can pretend the Earth is only 6,000 years old. But there’s nothing that quite seals the nincompoop deal like linking something—anything really—to autism. Don’t like sugar, gluten, junk food, meat? Tell people they cause autism. It’s the go-to, check-the-box, one-stop-shopping for know-nothingism.

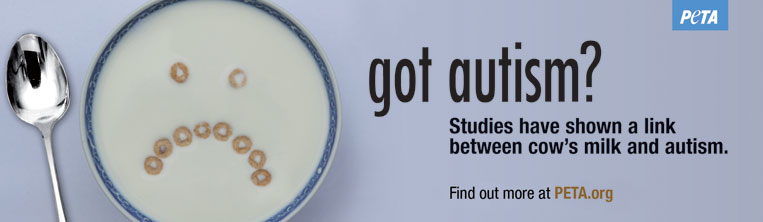

People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), which yields to no group in its ability to be outrageous, has mostly avoided that inevitable step. But in an earlier ad campaign that’s gaining new attention—and that remains on the group’s website—the folks who love animals but apparently have a cooler relationship with facts have come through big. The ad shows a bowl of cereal making a frowny face, accompanied by the slogan “Got autism?” The tag line elaborates on that provocative question: “Studies have shown a link between cow’s milk and autism.”

So where to begin—aside from the fact that no, studies haven’t shown that? OK, to be perfectly fair, when pressed, PETA does cite two scientific papers that seem to support its claim. One, published in 2002, observed some possible improvement in autism symptoms when children were put on a diet free of gluten, gliadin and casein, proteins found either in grains or milk. Not only is the study old, it’s vague—with the researchers broadly blaming the problem on “processes with opioid effect,” whatever that means. It was also tiny—relying on a sample group of just 20 kids. Finally, the study was admittedly single-blind, which means that the experimenters knew which kids were getting the special diet and which weren’t. Got bias?

The second study came even earlier—in 1995, which is the dark ages of autism research—and it was almost as small, involving just 36 subjects. It detected no real link between dairy products and autism, instead finding only antibodies to milk proteins in the blood of autistic children. That suggests, well, who knows what? Association, as people who understand basic science will tell you, is not causation, and blood chemistry is only a broad, imprecise starting point for proving a link between any suspected cause and observed effect in research of this kind. Nineteen years after the paper was published, its authors have not moved one step closer to drawing that line between milk and autism—and neither have the thousands of other studies that have come since.

PETA has been getting justifiably blowtorched for the ad since it was resurfaced by various media outlets in the last day. But even in light of the criticism and the science that shows no such effects of milk, the group stands by its insupportable claim, saying, in a statement, “PETA’s website provides parents with the potentially valuable information that researchers have backed up many families’ findings that a dairy-free diet can help kids with autism.”

Look PETA, activism is easy; scaring people is easy; making parents feel guilty because they fed their autistic child a bowl of Cheerios and milk is easy. Science is hard—which is why not everyone gets to do it.

Oh, and while we’re on that, you know what else is hard? Autism. It’s hard for the children who have it; it’s hard for the families wrestling with it; it’s hard for the researchers knocking themselves out every day to understand it and treat it and prevent it. They don’t need agitators and fabricators making things worse. There’s nothing wrong with protecting the animals, but try to do it without hurting the kids.

Correction: The original version of this article misstated when the PETA campaign on milk and autism began.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com