Alex Haley, author of the hugely popular 1976 book Roots, once said that black Americans needed their own version of Plymouth Rock, a genesis story that didn’t begin — or end — at slavery. His 900-page American family saga, which reached back to 18th century Gambia, certainly delivered on that. But it also shared with all Americans the emotional and intellectual rewards that can come with discovering the identity of your ancestors.

No one knew it at the time, but Haley’s best seller — and the blockbuster television miniseries that aired a year later — were the beginnings of a genealogy craze that would sweep the nation.

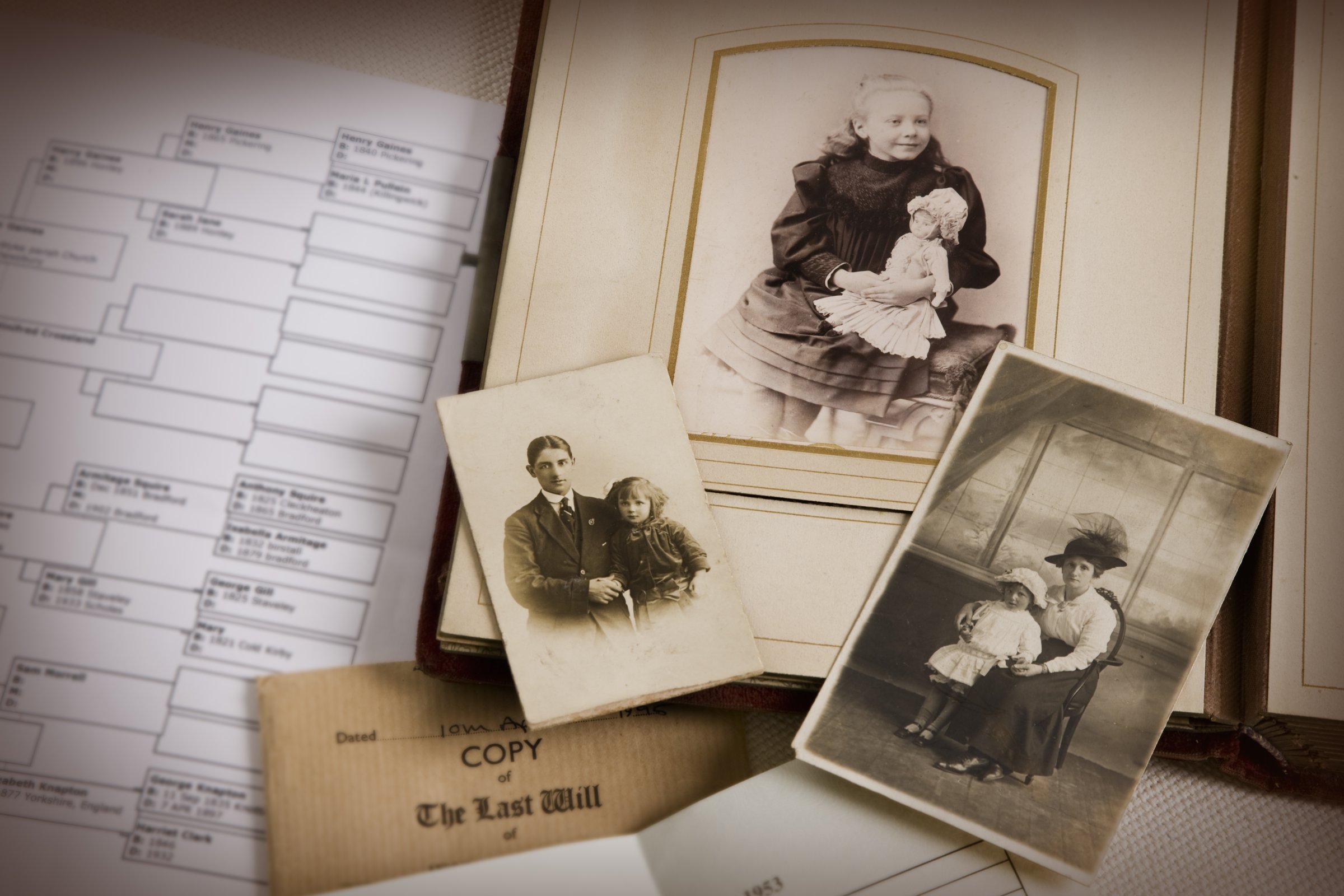

Four decades later, genealogy is the second most popular hobby in the U.S. after gardening, according to ABC News, and the second most visited category of websites, after pornography. It’s a billion-dollar industry that has spawned profitable websites, television shows, scores of books and — with the advent of over-the-counter genetic test kits — a cottage industry in DNA ancestry testing.

During and after the 2008 presidential campaign, the press had a field day researching the family histories of Barack and Michelle Obama. Indeed, the winner of that election first came to the public eye as the author of Dreams From My Father, what he called an “autobiography, memoir, family history, or something else” that was essentially the tale of a young man desperately trying to find his own identity by exploring his unknown family past.

Genealogy has always had a following in the U.S. But prior to the civil rights movement, which encouraged racial and ethnic minorities to embrace their previously marginalized identities, the study of family history was largely the province of white social climbers and racists. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with millions of southern Europeans arriving on American shores, white elites often sought to maintain their social status by promoting a definition of whiteness that excluded newcomers. Genealogy became a way for them to prove their credentials and gain entry into such hereditary societies as the Daughters of the American Revolution, which was founded in 1890 and stood for, in the words of its president general, “the purity of our Caucasian blood.”

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, such bald-faced white supremacy was in retreat, the vibrant immigrant identities of the early 20th century had largely been assimilated, and the women’s movement was challenging old-fashioned gender roles. In other words: the very institutions that once defined our ancestors’ identities were very much in flux.

All this tumult is what made identity crisis and finding yourself household terms. The publication, production and popularity of Roots were part and parcel of a newfound need to locate oneself in uncertain cultural terrain.

The great irony is that many Americans — particularly those who were several generations removed from the immigrant experience — were trying to find personal meaning in their ancestry long after their heritage ceased to play a meaningful role in their lives. In 1986 psychologist Roy F. Baumeister concluded rather cynically that genealogy’s popularity stemmed from the fact that it was the only “quest for self-knowledge” that boasted a “well-defined method,” whose “techniques were clear cut, a matter of definite questions with definite answers.”

Religion and technology helped make the search for those answers even easier. In the 1960s, the Mormon Church — which espouses the doctrine of baptism of the dead by proxy and encourages its members to research their unbaptized ancestors — opened branch genealogical libraries throughout the country. In the 1970s, these libraries began to receive more and more non-Mormon patrons.

In the 1990s, digital technology and the Internet revolutionized the way large amounts of information could be reproduced, transferred and retrieved. Moving genealogical databases online then made it possible for tens of millions more Americans to research their families in the comfort of their own homes. A hobby once dominated by persnickety elites was now fully democratized and focused on identity rather than pedigree.

A few years ago, my father spent a year researching his family roots. At the end of his journey, he presented each of his children with an ornate album containing his findings, which reach back to the early 18th century in what is today Chihuahua, Mexico.

While I admired the work he’d done and thought most of what he’d found pretty cool, none of it struck me as having the power to change the way I saw myself in the world. But that was before I looked more closely at the photocopy from the 1900 census he had placed under a laminated sheet. It was then that I discovered that my great-grandfather Federico Rodriguez, who worked as a smelter in a large copper mine in eastern Arizona, had arrived in the U.S. as early as 1893. Before, I had thought both my mother’s and father’s families came to the U.S. in the 1910s during the Mexican Revolution. We hadn’t known much about the paternal side of my dad’s family.

But suddenly, there it was: proof that my dad’s grandfather was living and working and raising a family in Arizona 19 years before it became a state of the Union.

It’s silly, I know, but every time I fly to the Grand Canyon State, I’m tempted to get off the plane wearing one of those black Pilgrim hats with buckles. Now I understand why so many millions of Americans love it. Genealogy is fun.

Gregory Rodriguez is the founder and publisher of Zocalo Public Square, for which he writes the Imperfect Union column. This piece originally appeared at Zocalo Public Square.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com