Pope Francis stopped his motorcade between scheduled events in Bethlehem on Sunday to pray before the massive concrete separation barrier that divides the Palestinian city from Israel, which erected the controversial wall a decade ago.

The surprise stop was the latest signal that the Pope backed what the Vatican had indicated in 2012 with its support for a U.N. vote to make Palestine a nonmember state: that it regards it as a sovereign state. In a speech earlier on Sunday the Pope called Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas a “man of peace” after paying him a courtesy visit, and referred to the Vatican’s good relations with the “state of Palestine.”

But Sunday’s unscheduled prayer had the weight of symbolic imagery. Israeli guards watched from a fortified guard tower overhead as the Pontiff stepped down from his Popemobile and made his way to what may be the most photographed section of the Wall, as the barrier is colloquially known — a graffiti-rich section that tourist buses pass by entering from Israel en route to Bethlehem, which along with the rest of the West Bank Israeli troops have occupied since 1967.

As security and staff formed a cordon through several dozen well-wishers lining the motorcade route, Francis made his way to the towering concrete wall. He stopped at a panel spray-painted, in black, “Pope we need some 1 to speak about Justice Bethlehem look like Warsaw ghetto” and, in red paint, “Free Palestine.” He bowed his head in silent prayer, laid his palm against the wall, and before leaving touched his forehead to it.

The episode lasted only a few minutes, but on a three-day visit to the Holy Land the Pontiff had billed as “strictly religious,” likely provided the iconic image of the trip. The Pontiff is known for identifying with the underdog, and in a visit that is of necessity mostly stage-managed, the visuals alone were exceptional.

It certainly pleased the Palestinians.

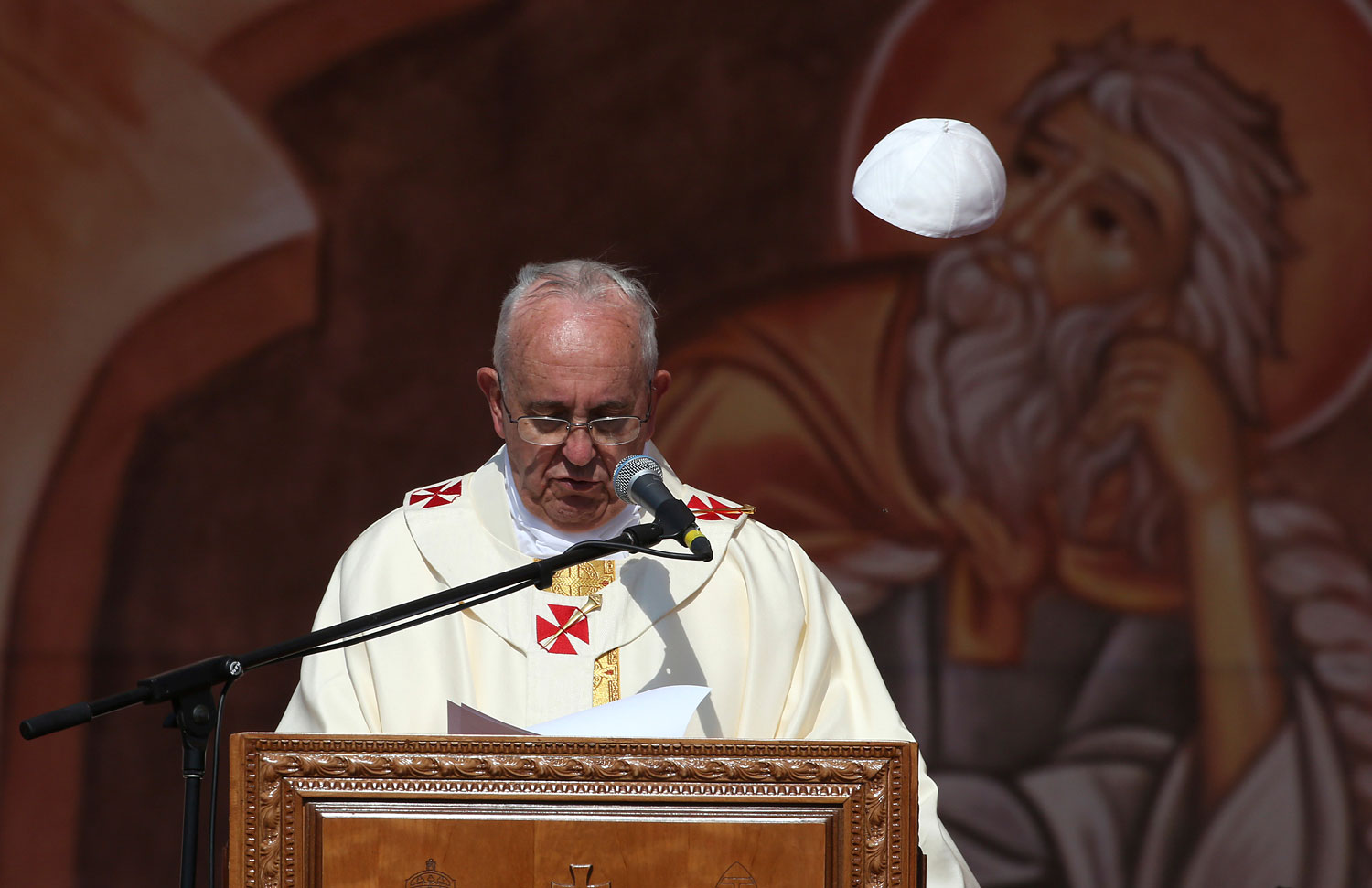

“He decided without anybody knowing that he would pass by and stop at the wall, and with the Israeli soldiers up there just looking down and not knowing what’s going on!” says Elias Giacaman, 32, a who saw the stop on the television mounted in the gift shop his family runs on Manger Square, where Francis arrived a few minutes later to preside over a Sunday morning mass.

“That has a lot of meaning, a lot of meaning,” adds Belinda Shamma, 53, a Palestinian Catholic who traveled from her Jerusalem home to the Bethlehem mass. “He is trying to tell the world what is happening to Palestinians is so unfair … We are dying inside.”

Analysts had already detected support for the Palestinian cause in Francis’ decision to helicopter from Jordan directly to Bethlehem, without stopping first in Israel. But local merchants clearly had too. T-shirts on sale at the event featured both the Pope and Abbas, plus Patriarch Bartholomew of the Greek Orthodox church, in a circle labeled “state of Palestine.”

The balance of the Pope’s time in Bethlehem was devoted to hearing complaints from Palestinians about the hardships of Israel’s occupation, including a visit with children from the city’s refugee camps, home to descendants of Arabs displaced since Israel was established in 1948.

Even the Pope’s decision to travel in an unarmored Popemobile was taken by some as a statement, given the security measures Israel has imposed as a matter of routine over the decades, which included two armed intifadehs, or uprisings. “Why not feel safe in here?” asks Giacaman, who is both Palestinian and Catholic. “He might feel unsafe in Jerusalem, not here, with those fanatical Jews around him.”

Francis was scheduled to arrive in Jerusalem later on Sunday, and — in part because of official concerns about religious extremists, security preparations were extraordinary even by Israeli standards, outstripping even precautions taken for President Obama’s visit last year, according to organizers.

The schedule for Monday includes deep bows to the Israeli narrative, including a visit to Yad Vashem, the museum of the Holocaust and to the Wailing Wall, the last remaining piece of the temple in place at the time of Christ. In a gesture that unsettles Palestinians, Francis will also be the first Pontiff to lay a wreath on the grave of Theodore Herzl, the founder of the Zionist movement that envisioned a future state on the land hundreds of thousands of Arabs called home.

Photos: The Pope’s Historic Holy Land Visit

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com