Artists are different from the rest of us: they make their pain public. Most people conceal their grievances under an official smile, fearful that the airing of any animosities will force confrontations and result in emotional defeat. Aspiring artists don’t care what their parents or peers think. They channel their resentments into a semiautobiographical first novel — or, in Xavier Dolan’s case, a first film.

Made when he was 19, with Dolan in the lead role, and detailing the betrayal he felt when his mother got exasperated by his antics and sent him off to a boarding school, the movie bore the ultimate Oedipal revenge title: I Killed My Mother. It fairly burst with teen trauma, and with the unassimilated visual influences of such auteurs of romantic angst as Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Wong Kar-wai. In its world premiere in the Directors’ Fortnight program at Cannes in 2009, the film won several awards, immediately establishing Dolan as the enfant terrible of French Canadian cinema. Tomorrow, the world.

Or rather, today. At a still-precocious 25, the former Montreal child star takes a more mature but endlessly provocative and exhilarating look at the same relationship in Mommy. In a somnolent Cannes season of too many disappointments from major directors and a tepid level of ambition, Mommy is precisely the electroshock jolt the festival needed. Like Blue Is the Warmest Color, which pleasurably startled audiences on its way to winning the Palme d’Or, Dolan’s film is intimate, emotionally choleric, sensational and a bit loo long (at 2 hours and 20 minutes). But its excesses are part of, at the heart of, its appeal. Beginning with a car crash and accelerating from there, Mommy administers primal therapy to its viewers and perhaps to Dolan himself.

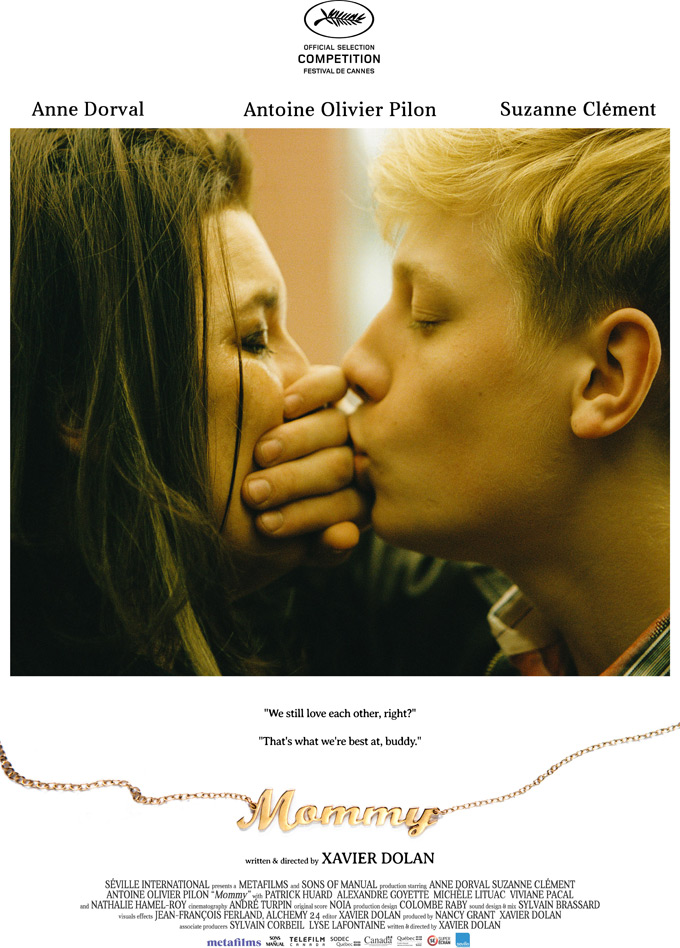

As in I Killed My Mother, the embattled mom is played by Anne Dorval. Suzanne Clément, a sympathetic teacher in the earlier film, takes a similar role here. The Dolan surrogate, the charming, troubled teen, is brilliantly assumed by Antoine Olivier Piton. This time, though, the viewpoint is reversed. Never condemning the son for his explosions, Dolan portrays the mother as a boundless fountain of tough love. She is Mommy dearest, without the twisted Joan Crawford irony. “Back in the days of I Killed My Mother,” Dolan says in the press notes, “I felt like I wanted to punish my mom. [But] through Mommy, I’m now seeking her revenge. Don’t ask.”

Widowed for three years, Diane “Die” Després (Dorval) cleans houses and occasionally translates children’s books. Her 15-year-old son Steve (Piton), afflicted with ADHD and given to violent outbursts, has started a fire in the school he’s been assigned to, causing the burning of another young inmate. Now Diane is to be Steve’s caregiver and teacher, while he would much rather be skateboarding or deliriously wheeling a shopping cart in traffic. Their verbal battles — in a raw Quebec patois that necessitated showing this French-language film with French subtitles — would singe the ears of the bickering couple in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? But at heart there is love: in Steve’s buying Diane a necklace with the word MOMMY, and in Diane’s indefatigable championing of her son.

They get unexpected help from their neighbor Kyla (Clément), a high-school teacher on leave for depression, who agrees to tutor the boy. She and Diane get along like loving sisters, especially when they open the box wine and dissolve helplessly into giggles. But Steve, who has inchoate dreams of going to the Juilliard School, hates the idea of sitting still for an education, testing Kyla with rude taunts. When he rips off her own necklace, she wrestles him to the floor and, her nose to his, fiercely lays down the law. His response is that of a frightened child or puppy: he wets himself.

Missing his late father, and trying to be the man of his house the blond, good-looking Steve naturally resents the lonely lawyer Paul (Patrick Huard) whom Diane befriends in hopes he can ease Steve’s legal problems. In fact, Steve bubbles with an adolescent sexual tension that keeps threatening to boil over into transgression. But in a film whose only two females are maternal figures, the prime, primal theme is the love everyone needs, not the sex everyone wants. “I’m afraid you’ll stop loving me,” Steve tells Diane. She replies with a mother’s melancholy truth: “What’s gonna happen is I’m gonna be loving you more and more, and you’ll be loving me less and less. That’s just the natural way of life.”

Set in “a fictional Canadian future,” Mommy is a film about right now and always, about any family’s bonds and how the members fight to strengthen or break them. Dolan encases the story of Steve and Diane in a nearly nonstop playlist of oldies — chosen, the director imagines, by Steve’s dead father — featuring Sarah MacLachlan, Céline Dion and, in a crucial scene set in a karaoke bar, Andrea Bocelli.

Dolan and cinematographer André Turpin chose an unusual screen ratio. Instead of wide screen they went for narrow screen, like a vertical iPhone shot, perfect for to capture the length of a body or the anguish on a face, and to dramatize operatic feelings in a narrow field. In only two sequences does the image expand to the full screen, when Steve or Diane imagines life without social or spatial confines — until the sides of the image start closing, like prison walls around a convict’s dreams.

There’s a chance the Cannes jury, headed by filmmaker Jane Campion, will share the enthusiasm of the early critics and award Mommy the Palme d’Or. That would make Dolan the youngest director to take the Festival’s top prize — one year younger than Steve Soderbergh when he won for sex, lies and videotape in 1989. Dorval, Piton and Clément would be equally worthy of individual or ensemble acting awards, so intensely committed are they to the film’s combustible story and characters.

But prizes are irrelevant to a film of suffocating power and surprising warmth. Stripping himself of his stylistic borrowings from other directors, Dolan has found his own urgent voice and visual style. Mommy doesn’t aim for classical grandeur. Instead, it bursts through the screen with the rough vitality of real people, who love not wisely but too well.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in Februar

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com