As the United States and Europe struggle to understand Vladimir Putin’s motives and goals—the subject of TIME’s cover story last week—it’s worth remembering that the West has been consumed by those questions before.

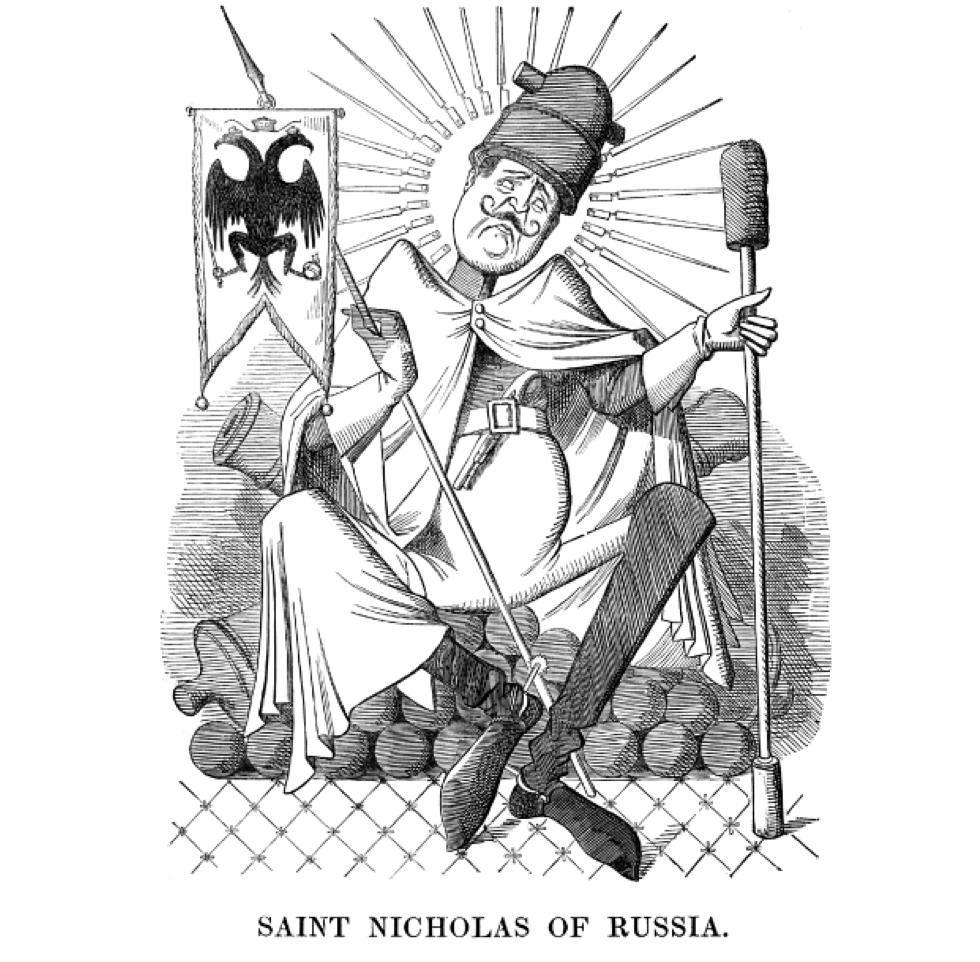

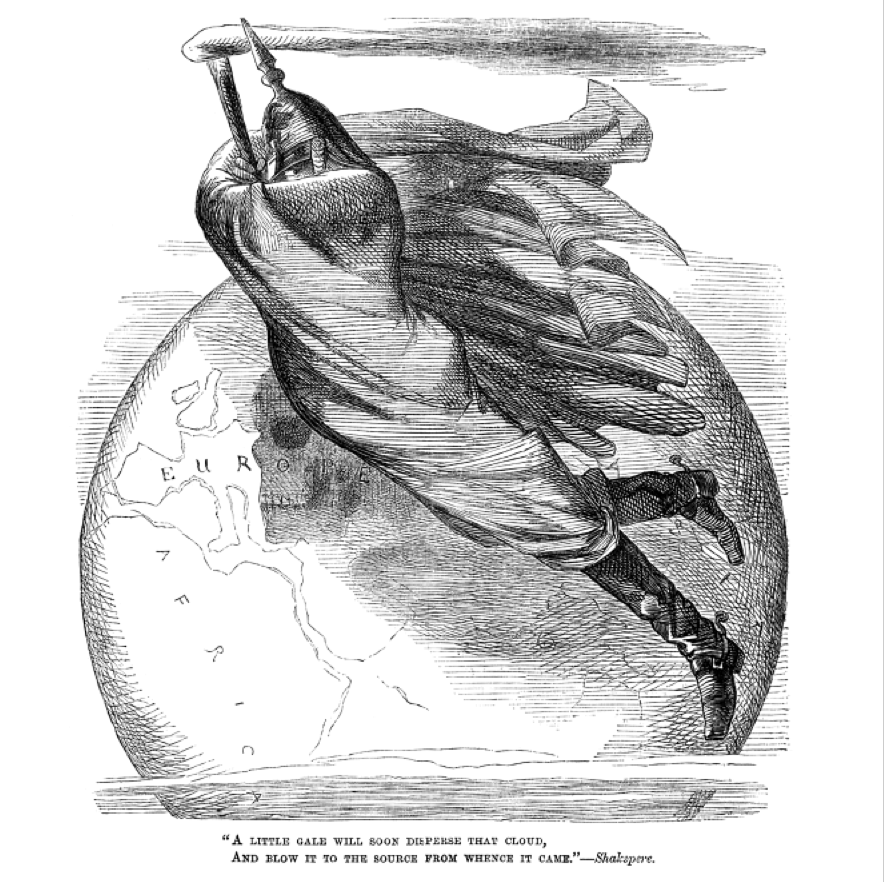

Yes, there was the Kremlinology and containment of the Cold War. But a century before brought a period of high Russophobia. In the mid-19th century, Europe was gripped with fear about Russia’s territorial ambition and consumed with how to stop it. Some of the echoes between then and now are downright eerie.

In the mid-1800s, Russia was controlled by autocratic ruler who distrusted Europe and sought to assert his nation’s greatness. This caused high alarm in Europe, and particularly in Great Britain—which worried that Russia might snatch its Indian empire. (This was a core component of the famous “Great Game.”)

One person sounding the alarm, as chronicled in this fine account of the time, was the British General and influential polemicist Sir Robert Wilson. The Russian Tsar Alexander was “inebriated by power,” he wrote in 1817. He was plotting to exploit European weakness for territorial gain. And he harbored grandiose visions of empire, perhaps even “to accomplish the instructions of Peter the Great”— who on his death bed called for massive Russian conquest.

Compare those ideas to today’s depictions of Putin. The Russian president is said to be “drunk on power.” His aggression is routinely cast as a response to the weakness of the West. He’s even depicted as going to bed at night “thinking of Peter the Great.”

And just as the West struggles to deter Russian aggression today, so did the Europeans of more than 150 years ago. One artifact of those debates is an 1828 manifesto by a British army general named George De Lacy Evans titled On the Designs of Russia. His bellicose pamphlet called for a pre-emptive war against Russia—something no one advocates today. But Evans did propose sending arms to countries on Russia’s western border, including Poland, much as today’s Russia hawks do.

Evans also proposed, in now-antiquated terms, the equivalent of today’s economic sanctions. Europe could curb Russia, he argued, by “cutting off her commerce, and thus placing the present pecuniary interests of the nobles at variance with the projects of the government.”

Substitute “oligarchs” for “nobles” and you have a core rationale for the West’s sanctions strategy.

These historical echoes are not lost on the Kremlin, which spins them as evidence that Russophobia—which achieved hysterical dimensions in the mid-1800s when one U.K. columnist joked that Alexander’s critics feared he would conquer the moon—has seized Europe.

Nor should they be. The escalating tension between Russia and the west produced the Crimean war of the 1850s, which left some 350,000 dead. Here’s hoping history doesn’t repeat itself quite so fully.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com