Short List

Person of the Year

The Short List

THE SHORT LIST: NO. 3

PERSON OF THE YEAR 2017

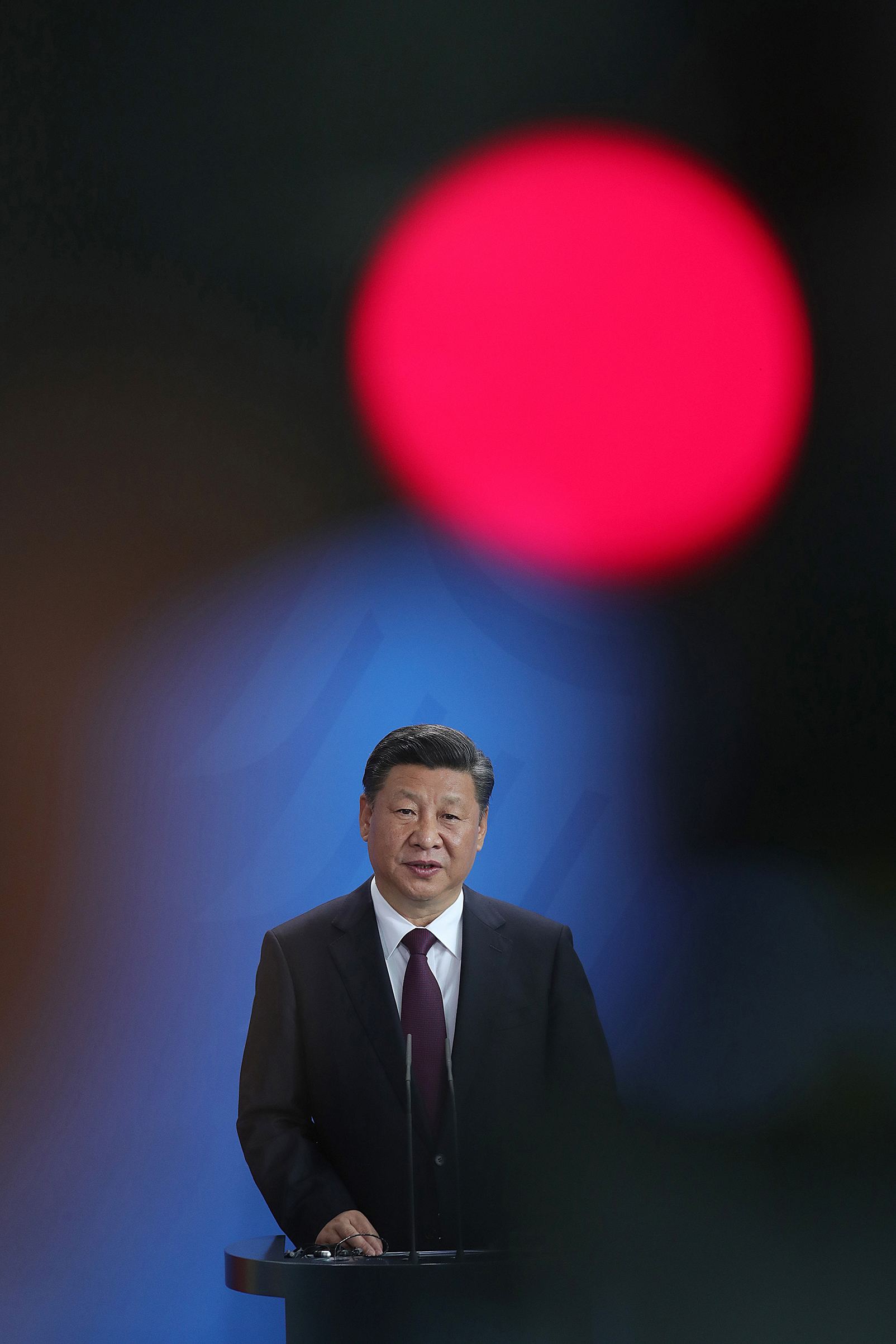

Xi Jinping

China’s leader vies for global dominance

Karl Vick and Charlie Campbell / Beijing

Sometimes things just seem to go your way. In 2017, Chinese President Xi Jinping strengthened his hold over the world’s most populous nation, was inducted into the pantheon of party leaders beside Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping and—small detail—announced that China henceforth intends to lead the world. He mentioned this deep into an Oct. 18 speech that ran beyond three hours, which begins to account for why so audacious a declaration drew relatively little notice. But then it also came after the President of the United States had signaled time and again over the previous 10 months that America might be surrendering the top spot. Drama requires conflict. This felt more like process. Donald Trump posted an unexpected vacancy, and China readied its application for the slot.

But fortune, as Louis Pasteur noted, favors the prepared mind. China’s leaders spent decades priming the country—historically viewed by the outside world as so insular that its national icon is a wall—to stake a claim for how it has always seen itself: the Middle Kingdom, at the center of the world. And it was no coincidence that its new ambition was announced by a leader so firmly in control that the party congress authorizing what should be his final term declined to designate a successor.

Watch: Why the Silence Breakers Are the 2017 Person of the Year

This year, Xi cemented his place as the most powerful Chinese leader since Deng, the visionary who turned China toward a market economy in the mid-’80s. In Xi’s first five years in office, he has reasserted the primacy of the Communist Party, fought government corruption, launched a global strategy of economic outreach and stoked Chinese nationalism while casting himself as a world statesman. At home he has cultivated both a bourgeoisie and a cult of personality, and has brought an iron fist down on advocates of free speech, an uncensored Internet, civil society and human rights. In the process, he has dashed the hopes of the Western governments that believed China’s embrace of capitalism would lead to democracy.

All that was clear even before Trump took office and pushed Xi’s influence to new heights. Shedding the U.S. mission statement that had shaped the modern order—to spread democracy, free enterprise and universal rights—Trump instead enunciated a mercantilist worldview where self-interest is all. Then he went to Beijing and told Xi that China was better at it. China deserves “great credit,” he said in November, for being able to “take advantage of another country for the benefit of its citizens.”

“Everything’s going to plan,” says Kerry Brown, director of the Lau China Institute at London’s King’s College and the author of CEO, China: The Rise of Xi Jinping. “If you were to write a work of fiction on how to have a perfect presidency, you couldn’t do better: no opposition, a strong economy and an American President who seems to be a bigger fan of Xi Jinping than Xi Jinping is himself.”

The question now is whether his fortune holds.

At 64, Xi has lived more than 20 years longer than the age a Chinese male was expected to reach in 1953. Life expectancy in the year of his birth was 41; today it’s 76. But his life has already been memorialized by the party he heads.

Xi was born into privilege, the son of Xi Zhongxun, a commander turned propagandist who, because his wife often traveled for her job at the Marxism-Leninism Institute, was unusually prominent in their family life. The third of four children, Xi was a princeling who was educated at elite schools in Beijing and thus insulated from privations like the famine that killed millions of people in Mao’s ill-named Great Leap Forward. But his father was purged from leadership positions, and in Mao’s Cultural Revolution the younger Xi was “sent down” at age 15 to live for seven years in the village of Liangjiahe. It’s now a pilgrimage site.

In the peak summer months, 5,000 visitors arrive at Liangjiahe daily, legions of them officials, or cadres, of the party. They listen carefully to the guides and note observations for reports they will write when they get home. Newspapers line the walls of the cave where Xi lived, and the bookshelves include not only Chinese classics but also Voltaire, Hemingway and Kissinger. “Everyone used to go to the Mao base,” says taxi driver Biang Sheng Li, referring to another pilgrimage site an hour away, where the Long March ended. “But since last year, even more people are going to Xi’s village.”

The intended message has taken root. “Xi knew people’s life and their hardships,” says Zhu Rong Xian, 40, a Hangzhou businesswoman who made the pilgrimage. “It made him a better leader.” In a green military cap with a red star, signaling political fealty to the party, and tasseled leather boots, Zhu had donned the clothes of the China that emerged, as Xi did, from the ashes of communalism.

The future President was an early supporter of Deng’s reform campaign, which embraced private business while maintaining a monopoly control of politics. Once rehabilitated, Xi’s father helped pioneer the special economic zones that tested the export-manufacturing economy that would drive China’s phenomenal growth for the next 40 years, fueled by cheap labor and U.S. investment. The son, after earning an engineering degree in Beijing and working briefly for the military, labored for a quarter-century in the provinces—the traditional proving ground for Chinese leaders. Terry Branstad, the current U.S. ambassador to China, remembers meeting him as governor of Iowa in 1985, when Xi was with a county-level delegation visiting the city of Muscatine. “What I found very different about him than other Chinese leaders I met with was that he’s much more outgoing and inquisitive,” Branstad tells TIME.

But Xi did not then stand out at home: when he ran for one of 150 openings on the Central Committee in 1997, he finished 151st (room was made). During most of his career, he has been overshadowed by his second wife, folk singer Peng Liyuan, whom he wed in 1987. By the time Xi did emerge in the senior echelon, the party was edging into crisis. Cadres had taken to capitalism a little too well, and the ruling legitimacy of the party was disappearing behind the tinted windows of the luxury Audis favored by even junior officials.

Xi emerged as the heir apparent in 2007 and oversaw the Beijing Olympics the following year—a lavish event that displayed unprecedented Chinese soft power to the watching world. His first act as General Secretary in 2012 was to set about cleaning up the party, ensuring that it made rules and not money. His anticorruption drive transformed public life. At the same time Xi was reopening 7,000 party offices, thousands of officials faced investigation—including many rivals. Golf courses shut down as Xi punished guanxi, the clubby networking dynamic that was once how business got done. Li Hua, a foreign-affairs official in China’s Xinjiang region, remembers feeling conspicuous for shunning marathon banquets in favor of jogging and reading history. “Before, that made me a loner and a source of suspicion,” he says. “But now—after the anticorruption campaign—it is quite normal.” Meanwhile, Xi made public visits to a humble Beijing dumpling shop, ordering steamed buns.

Corruption was not the only threat Xi perceived to party supremacy. Free expression, human rights, civil society and Internet freedom also became targets. After decades of carefully calibrating how much dissent to tolerate—an ambiguity that offered a measure of freedom for dissenters, and a stubborn hope for Western governments—China passed a series of comprehensive, harsh laws in the name of national security. “The main building blocks are now in place, so the idea of effecting change is more or less over,” says Peter Dahlin, a Swedish human-rights advocate. “For quite a long time, these developments have been cyclical in nature. But it is here to stay. It’s permanent, a new normal.”

Dahlin speaks from experience. In 2016, he was held for 23 days in what is blandly called a Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location, or a “black jail.” He was deprived of sleep but was not subjected to the torture that Chinese prisoners, beyond the reach of lawyers, endure. “For the first time,” he says now, at the midpoint in Xi’s tenure, “a major nation has legalized the systematic use of enforced disappearance.”

The founding myth of U.S. global leadership begins with the attack on Pearl Harbor, and a Japanese admiral fretting, “I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant.” Seven decades later, Trump revived the prewar slogan “America first,” suggesting that the giant was ready to lie down. Then he withdrew the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a trade pact intended to hold a rapacious China in check economically. When, in June, Trump announced the U.S.’s withdrawal from the international effort to slow climate change, the new President of France, Emmanuel Macron, privately declared in a summit: “Now China leads.”

And China was ready, finally. For decades, its leaders had heeded the advice of Deng: “Hide our capacities and bide our time; be good at maintaining a low profile; and never claim leadership.” China had already shrugged off any lingering sense of inferiority in 2008, when it surveyed the wreckage of the global recession from a safe perch. But 2017 marked the coming out. Four days before Trump’s isolationist Inaugural Address, Xi made his first trip to the gathering of the globalist elite at Davos. “We should commit ourselves to growing an open global economy,” he said. “Pursuing protectionism is like locking oneself in a dark room. While wind and rain may be kept outside, that dark room will also block light and air.”

At every turn in the months ahead, Xi told the world that China was no longer thinking only about itself. In March, it banned the trade in ivory. In May, Xi convened a summit on the Belt and Road Initiative, a $900 billion infrastructure project intended to bind Asia and Africa to China physically and economically, part of a larger effort to girdle the globe—from a highway in Pakistan to a port in Colombia—as the British Empire did a century ago. Like the British, what China has in mind is both profit and national glory. And it too has found an ally in the U.S.

“The U.S. was one of the countries that had done the most to help China modernize from the Maoist era, and there was an assumption that as China modernized and got wealthier, China would become more like the United States,” says Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute at the University of London. “That was never really realistically on the agenda, and now we know it’s not going to happen. But what is so extraordinary about Trump compared to other American Presidents is that no other person in the world—including Xi—has done more to make China great again.”

Having told his supporters on the campaign trail that the Chinese “rape our country,” Trump changed his tune in office, declaring that he feels “incredibly warm” about its President. His flattery adds to the glorification of “Big Uncle Xi,” as Chinese are urged to think of the leader who, after his campaigns to create “the Chinese dream” and “national rejuvenation,” reached for the ultimate prize on Oct. 18. “It is time for us to take center stage in the world,” Xi told the cadres.

There are reasons to doubt that that’s possible. China is certainly preparing itself for the future; with massive government support, it is positioned to surpass the U.S. in the next world-changing technology: artificial intelligence. It also excels in covert operations, including the major hack of the U.S. Office of Personnel Management, and by cultivating agents of influence at Western universities and in local politics. But its primary appeal to the world remains economic, with lending institutions like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. It faces the huge internal challenges of an aging population, an unworkable health care system, a halting transition to a service-based economy and a badly polluted environment. Trump may have abandoned the Paris Agreement, but U.S. carbon emissions are falling, while China’s continue to rise.

The military that Xi has given 30 years to become a global force is huge and newly assertive, but basically local: it opened its first overseas base, in Djibouti, only this year. State media refers to the disputed islets it expanded in the South China Sea—an aggressive assertion of regional hegemony—as “unsinkable aircraft carriers.” Of the floating kind, it has two.

Trump’s abandonment of core U.S. strengths—in his speech at the U.N. in September, he declined to take the side of democracy and universal freedoms—puts wind at the back of the nation’s totalitarian rival, whose rich but insular culture does not appear to travel well. “The bottom line,” says Brown, the Xi biographer, “is that China wants to have global reach, but it will be limited by its own nature.”

The West has not yet lost its luster. The U.S. gathers its power not just from its nearly 1,000 military bases but also from a magnetic, truly global popular culture, a premier higher-education system (which Xi’s daughter, a Harvard graduate, enjoyed) and an inclusive identity as a nation of immigrants. Since the collapse of communism as a global system, China no longer carries a unifying idea beyond its borders. Xi’s mantra is exporting “socialism with special Chinese characteristics.” No one seems to know what that means.

“I have asked many people: What exactly are you talking about?” says Elizabeth Economy, a China specialist at the Council on Foreign Relations. “Because as far as I can see, the Chinese model is a mixed market economy with significant state intervention, a repressive political system and corruption. Those to me are pretty much the three defining features of China over the past 40 years.”

Selling that in the world marketplace that Xi champions is the biggest challenge of all.

—With reporting by Zhang Chi/Liangjiahe

Lead photography by Krisztian Bocsi—Bloomberg/Getty Images