What the world needs to do to fight the deadly virus

The crowd was waiting. And angry.

As the Liberian Red Cross convoy pulled into a tin-roof shantytown at the base of Monrovia’s St. Paul Bridge, residents crowded the lead vehicle. The Red Cross workers were there to pick up the body of a man with symptoms of Ebola who had died the night before. “Where were you two weeks ago when we called when he had a fever?” demanded one resident. “I’ve been calling every day for an ambulance,” said another, brandishing the call log on his cell phone for proof. He turned to face the crowd: “No one comes when we are sick, only when we are dead.”

The Red Cross supervisor, Friday Kiyee, sighed as he launched into an explanation polished by constant repetition. “We are the Red Cross body-management team. Our job is to pick up dead bodies. We’re not responsible for picking up patients and taking them to the hospital.” He clapped his hands, a signal for the men on his team to suit up in their protective gear and pick up the body.

The work of the dead-body-management team of the Liberian Red Cross is hard enough; unprotected contact with the corpses of people infected with Ebola is dangerous and can easily result in infection. And the anger and frustration the workers face make their jobs all the more challenging. But there’s another factor that makes the work particularly draining: successfully containing the spread of Ebola is no epidemiological or biological mystery. During earlier Ebola outbreaks in remote, low-population areas, limiting infection was, in theory at least, relatively straightforward. Keep infected patients isolated during care, track down and monitor the people they’ve been in contact with, and ensure that the living keep clear of the dead. But in an uncontrolled outbreak in densely populated urban areas, the virus can burn like fire through dry tinder, and the sheer number of the sick makes those simple precautions all but impossible.

In Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone–the three countries most affected by the current outbreak, which is the worst since the virus was discovered in 1976–slowing the spread of Ebola has so far proved impossible for aid organizations, regional governments and the international community. “We know how to stop Ebola,” says Kiyee. “But we need help.”

That help hasn’t come fast enough. The scale of this outbreak is due in part to the fact that the virus hit cities for the first time, but it’s also because of a painfully slow response from regional officials and from abroad, with the disease’s spread outpacing aid. Far from bringing Ebola under control, we’re falling further and further behind, with the number of cases still increasing week by week. “We are not even at the point where this is at its worst,” says Amanda McClelland, who is coordinating the emergency response to Ebola for the International Red Cross.

The outbreak can seem a distant problem for many in the West, but on Sept. 30, American health officials announced that a man who had recently traveled from Liberia to Dallas had that day been diagnosed with Ebola. The case was the first diagnosis of the disease outside Africa, and while U.S. officials said they are confident they will be able to contain the spread of the virus in Texas, the announcement was a reminder of how easily Ebola can travel from the countries where it is raging.

By the end of March, when the outbreak in West Africa was just beginning, the death toll was 82. Now about 50 people die each day. More than 7,157 people have been reported as infected with Ebola, and 3,330 have died, according to figures released on Oct. 1 by the World Health Organization (WHO). Many experts believe the actual number of infections to be much larger, simply because there’s not enough personnel on the ground to keep track of–and care for–those who might be sick.

Compared with the hundreds of thousands of people who die from HIV/AIDS or tuberculosis in the developing world each year, Ebola’s toll so far is small. But it’s what could happen next that has public-health advocates and government officials around the world so scared.

On Sept. 26, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that if the current level of care were to stay the same, cases of Ebola in Liberia and Sierra Leone could double every 20 days, potentially reaching 1.4 million by mid-January. That projection is a worst-case scenario, but even if more aid arrives and the disease spreads at a slower rate, the swelling number of infections could exact a serious cost on the region that goes far beyond public health.

On Sept. 25, President Barack Obama told the U.N. General Assembly that the Ebola outbreak is “more than a health crisis. This is a growing threat to regional and global security. In Liberia, in Guinea, in Sierra Leone, public-health systems have collapsed. Economic growth is slowing dramatically. If this epidemic is not stopped, this disease could cause a humanitarian catastrophe across the region. And in an era where regional crises can quickly become global threats, stopping Ebola is in the interest of all of us.”

Recent pledges of manpower and money from the U.S. government, the U.N. and others will help, but some experts on the ground–like the Red Cross and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), medical NGOs that have been at the forefront of the Ebola fight in West Africa–are wondering why it’s taken so long.

“In the last few weeks, it’s definitely felt that we are gaining momentum,” says McClelland. “But we are going into our seventh month. And we were trying to wave the flag that this was a potential major threat, and we got no engagement.” That failure in Ebola’s early days and months, when the epidemic was still small enough to contain, has major consequences that are still being reckoned.

And the long-term impact could be devastating. The World Bank estimates that in its worst-case scenario, Liberia’s annual rate of economic growth could fall from 6.8% to negative 4.9%. There are other signs of social strain in the three countries hit by Ebola. “Schools are closed in all three countries. So there’s 7 million children without education, and there’s a huge number of people without access to normal health care,” says McClelland. “And the market prices are going up 15% to 20%. It’s really the humanitarian crisis that the fear and scale of the Ebola outbreak is creating.”

The Cost of a Late Response

It was April 2014 when the international community missed a key opportunity to contain the spread of the virus. An outbreak of Ebola was identified in a remote Guinean village in March, but since the virus often strikes in isolated rural areas, resulting in a flare-up that is usually contained within a few weeks, few paid attention. By the end of April, the spread seemed limited, and health authorities in the region breathed a sigh of relief.

But the lull was illusory. In fact, cases were going unreported, allowing the disease to spread from Guinea and Liberia to Sierra Leone. By mid-June, Ebola was back with a vengeance, hitching a ride with travelers out of rural areas to regional capitals like Monrovia, which has a population of about 1 million. There it had all the material needed for a viral inferno, including crowded conditions and a highly mobile population.

Even then, though, the international reaction was muted. After all, Ebola isn’t nearly as contagious as SARS, the airborne respiratory disease whose 2003 spread sparked a global panic and killed 774. Ebola could be controlled, the thinking went. The thinking was wrong.

Not everyone was convinced that the virus would fizzle out as usual. MSF had mounted a response as soon as the first cases were identified in March. By April, says Dr. Joanne Liu, MSF’s international president, the group was taking its concerns to WHO and the U.N. “We were saying, ‘It’s a huge epidemic,’ and I remember very well that WHO was saying it was under control.”

Meanwhile, Robert Garry, a Tulane University virologist who had been doing research on Ebola cases at a hospital in Sierra Leone, returned to the U.S. in May to report that the number of infections had been grievously underreported, with many infected people not going to the hospital–or dying before they could go.

Garry says he raised his concerns with the U.S. State Department and the Department of Health and Human Services. “The response was cordial, but nothing happened,” he says. “I was trying to show that we were at a tipping point and that this had the potential to spiral out of control.” By the time research on the virus by Garry and his team was published in the journal Science in August, five of the study’s 58 co-authors had been infected with Ebola and died.

Local governments weren’t responding fast enough either. A commonly expressed sentiment in Monrovia: The leadership didn’t respond to what should have been a national emergency until it threatened the capital. “As long as it was far away in the rural areas, no one paid any attention. But when it came to Monrovia, all of a sudden the ministers realized that they could catch it,” says Emmett Wilson, program manager for FACE Africa, a local development NGO. Assistant Health Minister Tolbert Nyenswah agrees that the national health system wasn’t prepared but argues that the government was doing the best it could under the circumstances.

On Aug. 12, the government announced a national ambulance hotline that Liberians could call to request safe transfer of patients suspected of having Ebola to designated treatment centers. But the hotline was quickly overwhelmed with calls–some 2,000 a day, says Nyenswah. There were only six government ambulances to answer those calls. Many who called had to wait several days for help–which is several more days that someone infected with the virus could pass it on to caregivers.

It wasn’t until August, after one American aid worker and an American doctor working in Liberia had contracted the virus, that the CDC sent its first “surge” of epidemic specialists to the region and WHO declared Ebola a global public-health emergency. “It took 1,000 deaths and five months before this was declared a public-health emergency,” says Peter Piot, director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and a member of the team of researchers who discovered Ebola in 1976. “It is always better to overreact than underreact in epidemics. Because of this delayed response, it’s much harder now.”

By the time the U.N. formed an emergency task force and made an appeal on Sept. 16 for nearly $1 billion to combat the disease, Ebola had infected at least 4,985 people, possibly far more. That same day, Obama committed 3,000 troops and $500 million to support the effort. The U.N.’s coordinator for Ebola, David Nabarro, said many countries have “responded with generosity.” But right now the disease is spreading faster than aid is arriving.

The Way Out

The same CDC modeling tool that predicted a doomsday situation of 1.4 million infections by January also revealed that the epidemic could be slowed and eventually stopped if 70% of people infected with Ebola were placed in settings where transmission could be contained. “That’s enough to break the outbreak,” says Dr. Stephen Monroe, deputy director of CDC’s National Center for Emerging Zoonotic and Infectious Diseases.

To accomplish that, WHO estimates that 1,990 beds will be necessary for Liberia’s current caseload, more than three times the current capacity. That shortfall should narrow with the arrival of the 3,000 U.S. troops, who are slowly being deployed and are tasked with building more treatment centers–but who won’t be permitted to interact with sick people.

Those boots on the ground will address only part of the problem: Ebola treatment centers require on average four highly trained staff members per patient–from a constantly rotating roster of doctors and nurses to disinfectant teams and janitors responsible for disposing of contagious materials. The disease has taken the lives of 92 local health care workers and has caused others to abandon their posts out of fear, so many of those doctors and nurses will have to be recruited from abroad. “Instead of 3,000 troops, it would be better to send 300 doctors,” says Daylue Goah, a communications specialist at JFK General Hospital, Liberia’s only hospital still open for non-Ebola-related issues.

So far, that kind of commitment has not been made. Some 130 nations have pledged support for the U.N.’s Ebola effort, but only $346 million has actually been donated or legally committed and only a few countries, including the U.K., China and Cuba, have sent doctors to the region. “It’s not enough to write a check,” says MSF’s Liu. “The reality is we need people in the field. We can’t just have more isolation centers with no one to run them.”

But for all the mistakes made in the early days of the Ebola outbreak, international and local efforts seem to be finally picking up speed. In Liberia a widespread education effort is starting to bear fruit. For the first time, in the week ending Sept. 28, the number of new reported cases per week declined slightly, though the CDC cautions that the dip could be a result of slow testing capabilities.

But the capacity to treat those who get infected is not keeping up. “An exponentially growing curve of cases demands an exponentially growing response,” says Yaneer Bar-Yam, a physicist at the New England Complex Systems Institute who has studied how infectious diseases spread. “If you don’t get on top of this in a short time, all bets are off.”

The Land of No Handshakes

On the surface, Monrovia looks like any other bustling African capital. Streets are snarled with traffic, restaurants are crowded, and sidewalk sports bars are packed with patrons cheering for their favorite soccer teams. But a closer look reveals a population living in fear.

Ebola is spread through contact with infected bodily fluids, and in a society habituated to close physical proximity, no one shakes hands anymore. On Sundays, churchgoers don’t sit so tightly together on the pews. Sports are discouraged. The city’s air is heavy with the antiseptic stench of chlorine disinfectant wafting from the hand-washing stations found at every street corner and place of business. Security guards posted at the entrance of office blocks and grocery stores wield infrared thermometers instead of guns and check the temperature of all who would enter–a high fever is one of the first symptoms of Ebola. And at a popular dance club, the house DJ warns patrons, “No too much rubbing, no too much hugging, no too much sweating … Don’t share drinks, and don’t have sex with someone you don’t know well.”

In a city stalked by death, there are no funerals. Proper disposal of Ebola’s victims is one of the most essential factors in stopping the spread, and with every corpse a potential viral bomb, nobody wants to take any chances. “We have to assume every dead body is a possible Ebola case,” says Assistant Health Minister Nyenswah, who is in charge of the Ebola response. That means that every corpse is bundled into a body bag, hauled onto the back of a Red Cross pickup and transported, sirens screaming, to a crematorium far outside town. There the dead, unmarked and unmourned, are burned in huge funeral pyres each night, the smoke going unseen into the dark.

The Crisis to Come

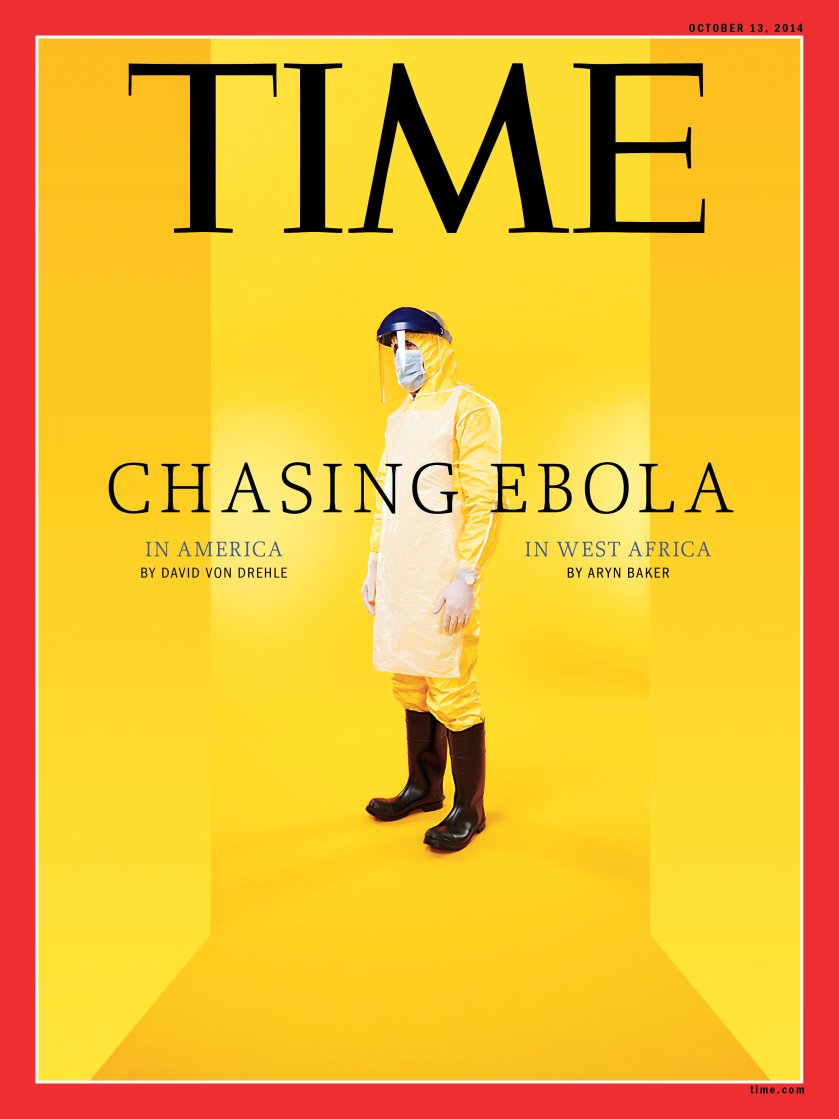

Health care workers in Ebola treatment centers labor under extreme duress, sweltering under layers of protective plastic to take care of patients who have a high chance of dying even with treatment. When even janitors must wear the cumbersome biohazard suits to do their work, getting a new treatment center’s team up to speed on the rigorous safety requirements can take several weeks.

The U.S. promised on Sept. 16 to train up to 500 health care workers a week for the Liberian effort, but officials have since backtracked on that pledge, acknowledging that it takes several weeks to safely prepare staffers for such a harrowing mission. “We don’t want to compromise quality,” says Dr. Frank Mahoney, co-leader of the CDC’s Liberia Field Team.

Meanwhile, Ebola’s toll in Liberia is compounded by a second, less obvious crisis–the utter collapse of a national health care system that is eroding what little success the international response has achieved in combatting Ebola.

Already weakened by a brutal civil war that cost over 150,000 lives before ending in 2003, Liberia’s health sector had only just started to recover when Ebola hit. Before the crisis, Liberia had less than one doctor per 100,000 residents, compared with 77 in South Africa and 245 in the U.S.; but with Ebola’s outsize toll on health workers, that population has plummeted.

Health clinics and hospitals across the country have closed for fear of infection, and as a result, once manageable illnesses–such as diarrhea, hypertension and diabetes–have become death sentences. “Ebola has sucked the air out of health care,” says Eric Talbert, executive director of Emergency USA, a San Francisco–based aid agency that partners with local governments to set up hospitals in countries coming out of conflict. “People with other communicable diseases are going untreated as Ebola rages.”

That will have long-term consequences if, as Piot of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine argued in a recent paper published in the New England Journal of Medicine, Ebola is in the region to stay. In that case, the Ebola response will have to move from a short-term intensive effort to stop transmission to an equally intensive long-term campaign to clean up in its wake. A vaccine made by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) and GlaxoSmithKline is currently undergoing human safety trials at the University of Oxford and the NIH’s campus in Bethesda, Md. But an effective rollout would still require a functioning and robust health care system. Not only does such a health care system not currently exist, but what’s there now is being eaten away by Ebola.

Even if the numbers of infections and deaths start to fall, there can be no sighs of relief this time around. Ebola will continue to smolder in the places where it can’t be tracked, ready to burst into flame the next time conditions are right. “The key now is to look to the future,” says Piot. “We have to make sure promises are implemented to a scale that makes a difference, and we need to test vaccines and treatments as soon as possible. We need to start thinking about how we will never let this happen again.” Arriving too late was a bad mistake. Leaving too early, before those systems are firmly in place, would be harder to forgive.

–WITH REPORTING BY ALEXANDRA SIFFERLIN/NEW YORK CITY

FOR MORE PHOTOGRAPHS BY DANIEL BEREHULAK, GO TO time.com/lightbox