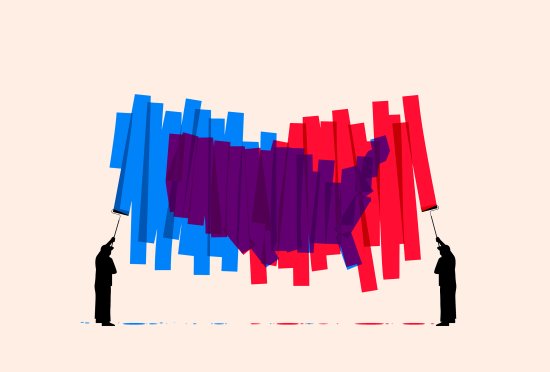

It is almost a truism that America is more divided than ever. In fact, it feels like our lack of consensus is the only thing there is a consensus about.

But go ask someone who just got an early release from federal prison about this idea of division. Go ask a coal miner, whose health care and pension the government recently saved. Talk to families facing America’s addiction crisis, as policies begin to shift to honor their struggle. Quietly, below the radar, a new kind of bipartisanship is emerging. It tells a different story about who we are as a country—and who we could become.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Bipartisanship today is different from the top-down bipartisanship of the 1990s and early 2000s, which gave the term a bad odor. That old approach—led by elite political professionals who ideologically were in the mushy middle—gave us NAFTA, prisons everywhere and endless wars.

As a result, people of strong political conviction on both the right and the left came to distrust anyone who talked about “compromise” and “reaching across the aisle.” And the grassroots—from Black Lives Matter to the Tea Party, from Bernie Sandernistas to the MAGA-hat crowd—revolted against the traditional dealmakers in both parties. The resulting partisan division has convinced the public that the parties can never cooperate on anything.

But that’s not true. Today’s bipartisanship is actually supported by strong partisans, not by weak moderates. And it is driven from below: not by timid insiders but by desperate outsiders whose communities have been let down and left out for generations.

I discovered this bottom-up bipartisanship while working to fix our criminal-justice system. In 2014, I helped launch #cut50—a bipartisan campaign to cut crime and incarceration in half. My progressive co-founders, Jessica Jackson and Matt Haney, and I had found strong conservative allies, including Newt Gingrich and Koch Industries’ Mark Holden. Through our work, which took me from South Central L.A. to the red parts of Pennsylvania to West Virginia and back again, I learned key lessons, working with “the other side.”

First, the most important formula for bipartisan breakthroughs: pay less attention to the politics at the top and more attention to the pain at the bottom. Pick tough issues that neither party has been able to solve. Only the best people in either party will touch those causes. So you will start out with great partners.

Second, separate battleground issues from common-ground issues. Some issues are still hot and divisive. State your differences on those issues—and then move on to areas where you can get something done. For example, I work with the libertarians at Koch Industries on criminal-justice reform while fighting them passionately on environmental policy. At the end of a conference call, I sometimes tease my right-wing allies: “O.K., now I gotta go beat you on all the other issues!” You can fiercely oppose someone on a battleground issue and still work with them on a common-ground issue.

Third, don’t convert. Cooperate! Don’t try to make other people adopt your worldview just to work on a problem together. I’ve found, for instance, that progressives working to fix the prison system are often motivated by empathy and a desire for racial justice. On the other hand, conservatives often want fiscal restraint, less government overreach and second-chance redemption for fallen sinners. We have different reasons, but we want the same result. Let that be good enough.

Fourth, start human, stay human. Respect that whoever you are working with on the other side has noble ideals and values. Don’t make them bear the cross for the misdeeds of the worst elements in their own party. They can’t control their yahoos any more than you can control yours. And when disagreements arise, don’t call people out, based on your set of principles. If anything, try to call them up to a higher commitment—inviting them to better honor their own principles.

Of course, after Trump’s win, I felt squeezed by a moral dilemma. As a progressive, I will always fight policies I see as anti-immigrant, anti-environment, etc. But a deeper question vexed me: Was resistance enough? Would simply opposing Trump solve the underlying social problems that predated and helped fuel his rise? And how should I relate to Trump’s voters? Condemn them or work to better understand them? After all, I had long cared about people trapped in urban and rural poverty. Should I stop trying to alleviate suffering in both red counties and blue cities to focus instead on discrediting 45?

Ultimately, I decided to stick to the principles I’d learned in the pre-Trump era and keep working across ideological lines. I’m glad I did. In recent years, left-right alliances have passed justice-reform bills in several states. In December 2018, President Trump signed the First Step Act, a bipartisan measure making rehabilitation (rather than mere punishment) the federal prison system’s goal. The bill has already accelerated freedom for more than 5,000 people. Trump deserves more credit for rallying the GOP to break D.C.’s long-standing logjam on this issue. That win expanded hope and made prison reform safer ground for both parties.

But criminal-justice reform isn’t the only issue where working together can lead to results. Just last year we saw another example of a bottom-up movement that secured a bipartisan win when sick, retired coal miners led a grassroots movement that persuaded congressional leaders in both parties to save their pensions and health care.

There are at least three other areas where Americans could make similar progress.

Start with addiction. When the face of addiction was black, our government saw addiction as a crime, not a disease. Thirty years ago, America shamefully filled its prisons with young men of color. Today, as the body count has risen in whiter parts of the industrial heartland and Appalachia, the public rhetoric has been more sympathetic. But progress has been too slow. There remains great wisdom in urban America about how to respond compassionately and effectively to people trapped by drugs. Sadly, rural white leaders have not yet had the good sense (or national contacts) to reach out to black America for help. And black, brown and urban leaders have not yet had the heart (or bandwidth) to offer it. But a rural-urban alliance to fully decriminalize addiction would have great appeal and power.

Then there’s mental health. There is a homicide crisis in urban America, and too many African Americans and Latinos have attended too many funerals and buried too many sons and daughters. Meanwhile, there is a suicide crisis in suburban and rural America, with rates skyrocketing, especially among young women and older whites. And too many of our veterans, abandoned after a generation of war, face PTSD and other diagnoses without the support they need. These vets are as likely to come from inner-city Detroit as rural Georgia. This trauma needs treatment on a mass scale, and a stronger blue-red alliance is waiting to be formed.

Finally, there’s intergenerational poverty—from Appalachia to the ’hood. The truth is that there is no such thing as a liberals-only or conservatives-only solution to entrenched poverty. Low-wealth communities need government intervention through some combination of social programs, tax credits and Opportunity Zones. But to benefit from these measures and succeed, an individual also needs the traditionally conservative personal values of hard work and thrift. Real solutions require both social and personal responsibility.

In other words, we need each other. To uplift those whom Jesus called “the least of these,” we don’t have to convert or annihilate each other. Liberals can stay liberal; conservatives can stay conservative.

Liberals fight for social justice, while small-government conservatives fight for liberty. Both traditions are necessary for America to have liberty and justice for all.

To end the food fight at the top of our political parties, we need strong partisans at the bottom working together. Bottom-up bipartisanship can solve the problems that top-down bipartisanship created. Common pain at the grassroots level can lead to common purpose, common ground and commonsense solutions. Even now.