How Coach Prime is changing college football forever

On an autumn weekend in Boulder, the sports miracle of the season is clearer than the blue Rocky Mountain sky. Whereas for years, the University of Colorado football team delivered Saturday misery—the Buffaloes enjoyed just four winning seasons in the past 20 years and finished 1-11 in 2022—Boulder now may be the hippest, happiest place in America. “The Stampede,” a Friday-night pregame pep rally down Pearl Street, used to feel more like a tiptoe. But on Sept. 29, the night before Colorado faced off against No. 8 USC, the restaurants are full and the sidewalks packed. A handful of little kids even line the rooftop of a trattoria to watch the marching band play.

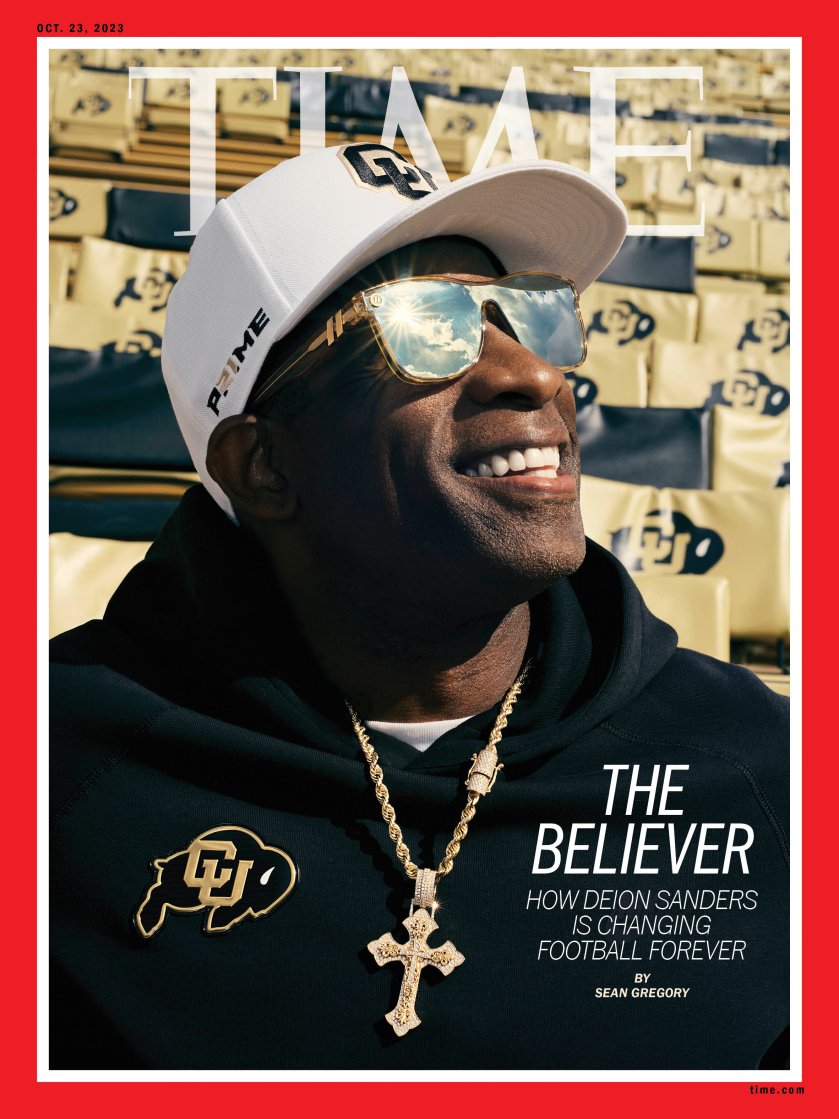

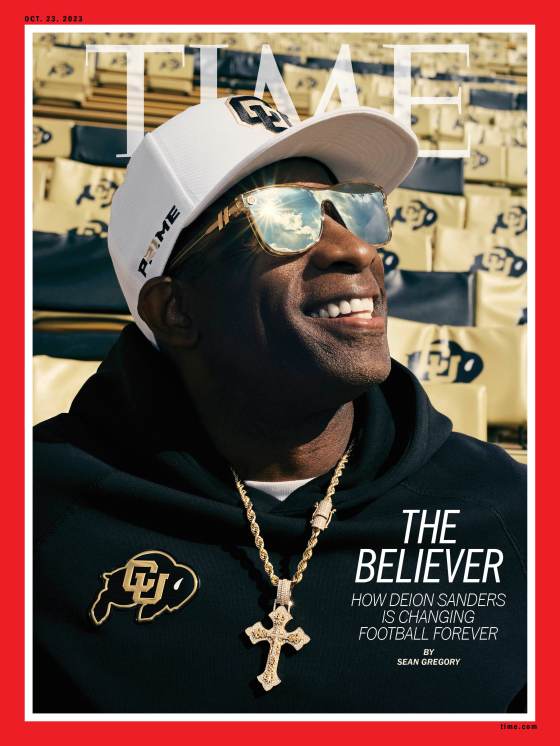

A little before 6 a.m. Mountain time the next day, hundreds of University of Colorado fans, most wearing white cowboy hats adorned with LED lights, have assembled on Farrand Field, smack in the middle of campus. Some are students, others alums and locals, while a significant number have traveled from far afield, never having imagined they’d have reason to gaze at those picturesque peaks in the backdrop. Fox Sports’ Big Noon Kickoff pregame show won’t start for hours, but the revelers are ready. They’re here to see Deion Sanders, or Coach Prime—a play on Prime Time, his nickname from his 1980s and ’90s heyday—who arrived as head coach in December, radically made over this year’s team, and turned Colorado into the biggest story in sports.

Before kickoff, the sidelines at Colorado’s stadium are now the place to be seen. There’s rapper DaBaby hyping up the crowd. There are Sanders’ friends and fellow football Hall of Famers Terrell Owens, Warren Sapp, and Michael Irvin. Hey, that’s basketball Hall of Famer Kevin Garnett and future baseball Hall of Famer CC Sabathia and rapper Symba. The VIPs wear a special credential around their necks: Prime Passes, in the shape of the gold whistle Sanders uses in practice. Boulder County is 1.3% Black, yet as one sideline spectator observes, the scene “feels like Black Hollywood.”

And what’s been happening on the field is as spectacular as what’s happening off. As the Buffaloes charged back against the Trojans, slicing a 41-14 third-quarter deficit to 48-41 with just under two minutes left, Folsom Field, filled with more than 54,000 roaring fans, felt like the epicenter of sports. Could Sanders’ squad, which had already exceeded expectations, stimulated the college-football economy, and compelled more than 8 million people to watch Colorado beat Colorado State in double overtime after 2:15 a.m. Eastern time in mid-September—ESPN’s highest college-football viewership figure at that hour—pull off this monumental comeback?

USC recovered the late onside kick to clinch the game, but Colorado’s charge just added to the Coach Prime euphoria. “The atmosphere is electric, man,” DaBaby tells me before leaving the field. “Look, f-ck the NFL game. Right now this is the most exciting place to be in football.”

More From TIME

Swifties may disagree. But while the rumored relationship between Taylor Swift and Kansas City Chiefs tight end Travis Kelce drives headlines and ticket sales, Coach Prime’s efforts are much more far-reaching. At Colorado, he has the power to change not only the fate of the team but also the multibillion-dollar college-football industry. His success could open doors for more Black head coaches at the highest levels of the college game, a long overdue development especially given that teams with majority-Black players help generate, in some cases, north of $100 million in annual revenue for their schools. After decades of coaches “protecting” players from “distractions,” Sanders has invited cameras to embed with Colorado for the second season of Amazon’s Coach Prime. His embrace of social media exposure for players—they wear their Instagram handles on their practice jerseys—and their recently won right to capitalize on their name, image, and likeness (NIL) should shake up the sport’s stodgy DNA. Plus, after two successful seasons at Jackson State, a historically Black college or university (HBCU), Sanders used the “transfer portal”—the still-newish NCAA mechanism that lets players switch schools without sitting out a year—to overhaul Colorado’s roster. He brought in 57 transfers, while more than 60 Colorado players left for other programs or ended their college-football careers.

In short, he treats college sports as what it is: a business. CU hired him to win, and win now. And he’s doing it his way, with straight talk and unshakable confidence.

“In the world of college football, there is a certain expectation of how coaches should be and how they should act,” says Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, a former defensive lineman at the University of Miami who won a national championship in 1991. “Prime tore that playbook up and threw it out the window.”

Read More: Jalen Hurts Is Fueled by the Doubters

Some of Sanders’ methods have proved unpopular. He was criticized for having DaBaby, who has been decried for using homophobic language and has had multiple run-ins with the law, give his team a pep talk about overcoming adversity. He’s pushed players out the door. Many people are rooting for his failure. But that word, Sanders insists, isn’t part of his vocabulary. Love Coach Prime—a ubiquitous presence in ads for Aflac, California Almonds, and KFC—or hate him, you’re paying attention.

“We’re being unapologetically who we are,” Sanders, 56, tells me in an interview in Boulder the week of the USC game. “You can tell, by everything that we’re accomplishing right now, that we’re headed in the proper direction at a speed that is undeniably a lot more expeditious than many people would have suspected. Shoot, this is going to be good. It’s just like the trailer of a movie you’re seeing. Just wait until you see the whole dern movie.”

Sanders patrols his team’s morning practices on a golf cart with “Prime” emblazoned on the front (a “Prime” bicycle and “Prime” Segway rest outside his office). Before one session, the team huddles around him. “Line, you’re going to have a great day. You’re going to kick some butt up front, right?” Sanders says. “Yes, sir,” players respond in unison. “You’re going to protect that quarterback, right?” “Yes, sir.” “Defensive line, we’re going to get to the quarterback, right?” “Yes, sir.”

He drives from station to station to observe and occasionally weigh in. Sanders moves more gingerly these days: due to blood clots, he had two toes on his left foot amputated in 2021. “Get off the field! Garbage! That’s horrible!” he says to one player who erred. “You ran onto the field as if you are about to have a baby in three months,” he tells a player who wasn’t hustling enough for Coach Prime’s liking. “Hey guys, that was horrible offensively today, I want y’all to know that,” Sanders says at the end of a practice. “There’s not a commitment to excellence whatsoever. You’re just going through the dern motions.”

Sanders eschews profanity, often saying dern where a curse word would do. But he reserves his biggest smile of the week for when two of his coaches—defensive coordinator Charles Kelly and defensive-tackles coach Sal Sunseri, both of whom left Alabama, the premier program of the past 15 years, to take on this rebuilding project—get into a shouting match that devolves into an exchange of F-yous. He appreciates their intensity.

At one practice, David Kelly, Colorado’s general manager and a longtime Sanders confidant, shows me a text he got from Nike co-founder Phil Knight, who had talked to Sanders before Colorado faced Oregon in Eugene on Sept. 23 and met with Barack Obama at Nike headquarters a few days later. “I greeted him with, ‘you’re the second biggest celebrity I’ve talked to this week,’” Knight wrote.

Little about Sanders’ program is typical. “Is You Working or Twerkin?” reads a sign on Sanders’ office door. (Working or twerking is one of multiple phrases, including Coach Prime and It’s personal, for which he has filed for trademarks.) A conference room houses his sneakers and hats. On Friday afternoon, a woman walks toward his door and asks, “Are that many people really in there?” Sanders doesn’t allow shoes in his office, and 11 pairs of shoes sit in front of the reception desk. A few minutes later, members of the documentary crew; his manager; Sanders’ son Shilo, a Colorado safety; Garnett; and fellow basketball Hall of Famer Paul Pierce file out of Sanders’ space.

These days, everyone wants time with Prime. Colorado’s game against Oregon, a 42-6 blowout victory for the Ducks, drew 10.03 million viewers, making it one of the most-watched college-football games of the year. The school’s online team-store merchandise sales are up 892% year-to-date over 2022. Colorado chancellor Philip DiStefano says out-of-state applications have climbed 40%. “It’s transformational,” he says. Sanders is even developing a half-hour comedy with Kevin Hart’s media company based on his journey and billed as “Entourage meets the gridiron,” Sanders’ team tells TIME exclusively.

Read More: The Most Influential People of 2023: Patrick Mahomes II

“People are drawn to hope, man,” says Sanders. “Shoot, we’re David. We ain’t got but a couple of stones here. We’re playing against Goliath every week. We were 1-11, and now you’re tripping about us? We’re pulling people in, man, that just want a chance to be seen, to be heard, to be noticed, to be recognized. They just want to be pushed in the swing set of life every once in a while and say, ‘Wheeee, wheeee.’”

One could dismiss these words as self-serving, if Sanders weren’t onto something. Because it’s not just celebrities who have flocked to town to pay homage to Sanders. (The Rock, Lil Wayne, Offset, and Key Glock have also made appearances since the start of the season.) Fan after fan in Boulder mentions Coach Prime’s inspiration. At the Colorado team store, Veronica Jones, a retired law-enforcement officer from Charlotte, N.C., wearing gold-rimmed “Fierce But Fabulous” glasses and a T-shirt for the HBCU Johnson C. Smith University, fished for Prime gear in the same area as a guy who looked like a member of ZZ Top. Her husband Wil Jones noted that most of the Black passengers on their flight to Denver were going to cheer on Sanders. “It was like a family reunion,” he says.

Kedric Mallory made the trip from Atlanta with friends and family, including his 1-year-old son. “I’m here to support the movement,” says Mallory, a real estate broker. “In my 42 years of living, I never thought of coming to Colorado. My son could have stayed at home with his grandmother. But I want him to be able to say, ‘When I was 16 months old, I witnessed the Prime Effect.’”

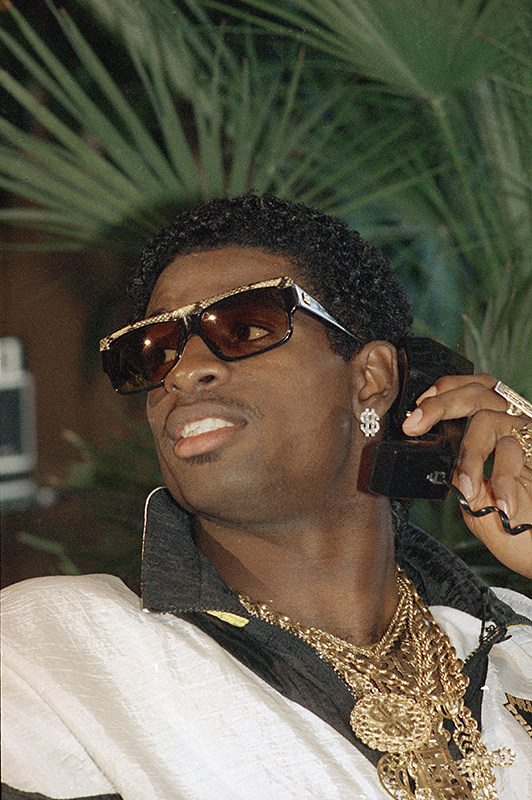

When Sanders was rocking Jheri curls and gold chains in the late 1980s—Neon Deion was another nickname back then—few would have pegged him for a major-college football coach, provider of hope, and leader of men. His talent was indisputable. But his swagger rubbed many the wrong way. “Everybody occupies two persons in their natural being,” says Sanders now. “People wish they could develop that other person a lot more. That other person says the things they want to say and does the things they want to do. Prime has been that cat. And I developed that cat a long time ago.”

Sanders grew up in Fort Myers, Fla., where his mother worked around the clock to support him. A two-time All-American at Florida State, Sanders won the Jim Thorpe Award, given to the top defensive back in the country, in 1988. Both the Atlanta Falcons and the New York Yankees drafted him. During a 1990 Yankees–Chicago White Sox game in the Bronx, Sanders got into a verbal exchange with White Sox catcher Carlton Fisk, who took exception to Sanders’ failing to run out a pop-out. Contemporaneous news reports said Sanders drew dollar signs in the batter’s-box dirt. Fisk seconded that account over the years. The exchange contributed to Sanders’ image as an arrogant heel.

But Sanders insists he drew no dollar signs, only markings to help position his feet. “Carlton Fisk lied,” he says. “Sir, with all due respect, I would never do such a thing.” (“Why would I lie about something like that?” Fisk says. “Check the tape.”)

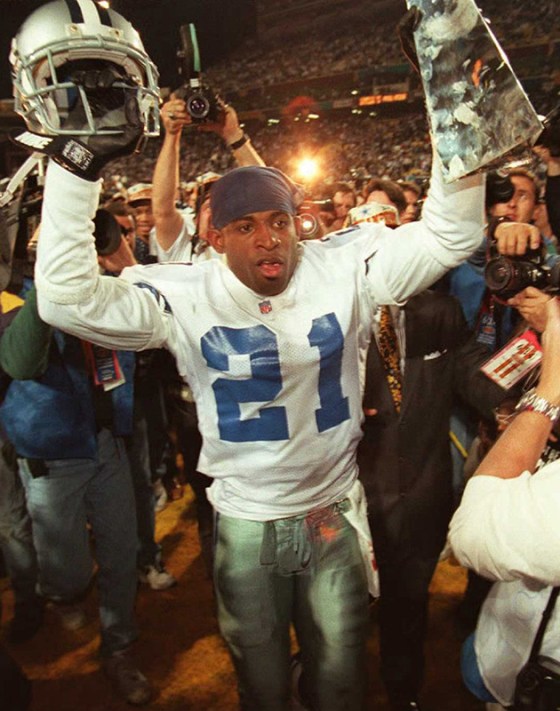

Regardless, Sanders rocketed to 1990s stardom. He made a cameo in MC Hammer’s “2 Legit 2 Quit” video. He won back-to-back Super Bowls after the 1994 and 1995 seasons, with the San Francisco 49ers and Dallas Cowboys, respectively.

Years before Colorado, Sanders was creating culture. Dwayne Johnson was watching closely during these years. Over Zoom, I ask him about Sanders’ influence on his own career, and he shows me goose bumps on his forearm. “No one has ever asked me that,” he says. “So much of the character and the entity of the Rock came from Prime. One of the characteristics of the character of the Rock was talking in the third person. Deion would say certain things in the third person. I always found that so f-cking cool. Because he walked the walk.”

After his NFL career ended in 2005, Sanders became a TV analyst and began coaching on the youth and high school levels when two of his children who now play for Colorado—safety Shilo, 23, and quarterback Shedeur, 21—were kids. In 2019, Sanders told his manager and business partner, Constance Schwartz-Morini, he might reach out to his alma mater about helping with recruiting. “I said, ‘Why don’t you just be a head coach at a college then?’” says Schwartz-Morini, CEO of SMAC Entertainment. “I’m not stupid. I understand there’s a huge difference between coaching youth and high school and jumping into the collegiate level. But while the real estate may change, his methods have not.”

He interviewed at Florida State and Arkansas, but without any college experience, he couldn’t get those jobs. Jackson State, which plays a level below major programs like Colorado in the Football Championship Subdivision, took a chance on him. Star power allowed Sanders to skip the typical assistant’s route. It didn’t matter: he finished 27-6, winning a pair of Southwestern Athletic Conference championships. “I hate when people say dumb sh-t, like he didn’t pay his dues,” says his former Cowboys teammate Michael Irvin. “OK, how many of you head coaches in college right now started at the Little League level? If I’m going to be a great CEO one day, I want to start in the damn mail room, so I can learn every piece of the job along the way.”

Sanders caught the attention of the big schools. As Colorado struggled last season, its athletic director, Rick George, started texting him pictures of Folsom Field’s mountain view. When he met with Sanders in mid-November, at Sanders’ home in Canton, Miss., Sanders surprised him with a written assessment of every Colorado player. Sanders took the job without visiting Boulder. “You choose this naked and not ashamed,” he says.

He took heat on the way out of Jackson. Sanders had helped draw much-needed attention and resources to an HBCU. So his exit, for some, felt like a betrayal. A commentator said on CNN that “he sold a dream and then walked out on the dream.” To Sanders, however, his work in Jackson was done. “It wasn’t like we just abandoned it,” he says. “What more can I do?”

During his first meeting with Colorado’s holdover players in December, Sanders, who signed a five-year deal worth $29.5 million, was brutally honest about his intentions. “Those of you that we don’t run off, we’re going to try to make you quit,” he said in a speech broadcast on social media.

Sanders acknowledges that come season’s end, some of his players will surely hit the transfer portal. With opportunities to earn playing time—and cash—elsewhere, churn is now part of college football. While players don’t get paid by their universities, as of July 2021, NCAA athletes can earn income through third-party sponsors and boosters. Shedeur, for example, has deals with Gatorade, Beats by Dre, and Topps, among others. According to On3.com, he has a $4.8 million NIL valuation, second only to Bronny James, LeBron’s son. Colorado two-way player Travis Hunter also ranks in the top 10. “They want to be treated like pros, but you’ve got to understand, now there’s scrutiny like the pros,” says Sanders. “There’s cuts. There’s dissatisfaction. So you can’t have a pity party and want it both ways. ‘Well, I’m still a kid.’” He says that in a baby voice. “No, no. You’ve got a Benz parked outside.”

After Oregon humbled Colorado, many celebrated Coach Prime’s comeuppance, which felt a bit odd given how recently the Buffs were 1-11. Don’t Americans root for the underdogs?

I ask Sanders to explain this one afternoon as we sit in the Colorado recruiting lounge, a spacious area overlooking the football field designed to impress prospects. His Belgian Malinois, Gunner, watches from a cage by the window, marking the first time a college coach’s dog has listened in on one of my interviews. “You know why,” says Sanders. “Everybody knows why. Nobody will say it.”

We put the cards on the table. Does he sense a resistance to a Black head coach who’s known to break protocol?

“If somebody has on a shirt that has wrinkles on it, I’m going to say, ‘Hey man, is your iron OK?’” says Sanders. “I’m not going to pretend it’s not there. I’m too old to play games. I’m not one to sit up here and wave the racial flag because I’ve been given some tremendous opportunities.” But the stats—just 10% of top Division I head coaches are Black—make it hard to argue that racism doesn’t persist in the sport. “We can play, but we can’t coach?” says Sanders. “Seventy percent of us can be in the locker room, but we can’t lead ourselves? It don’t add up.” Sanders vows to fix this discrepancy. “The Bible says, in Ecclesiastes, there’s a time and a season for every activity under the sun,” he says. “I believe it’s time that we make those strides.”

Opponents are taking shots at Sanders too. He didn’t appreciate comments from Colorado State coach Jay Norvell, who before the CU-CSU game said, “When I talk to grownups, I take my hat off and my glasses off,” a reference to Coach Prime’s sartorial choices. (Sanders’ sunglasses collaboration with Blenders then sold $1.5 million in preorders in one day.) Oregon coach Dan Lanning told his team in the pregame locker room that “they’re fighting for clicks, we’re fighting for wins.”

“You’ve got to understand where that comes from,” says Sanders. “That comes from something that’s deep down inside of him. That the pressure of that moment forced it out. He couldn’t hide. Successful people and confident people don’t do that.” Sanders notes he hasn’t initiated spats with other coaches. “Putting you down doesn’t lift me up,” he says. “We’re not on the seesaw of life.”

I mention that Shilo was caught on a film cursing at Ducks players before the game. “Shilo is Shilo,” Sanders says. “Shilo has been like that since he was a kid. Shilo doesn’t really start it. He finishes it. I’m pretty sure he was provoked in some kind of way.” For his part, Shilo insists he trash-talks his own teammates, including his brother. “They provoked me by just being there,” he says of Oregon. “They just look at you, and you just want to slap them.” (An Oregon spokesperson declined to comment.)

The comeback against USC offered a glimpse of the Buffs’ potential. If Colorado plays as strong as it did against a top-10 team for a full game, instead of just a half, it could contend in year one of the Coach Prime era. After the game, players bowed their heads as a Sanders friend led the team in prayer. “Lord … This is a day of resurrection. Thank you that you got the bitter taste of last week out of our mouths.” Sanders told his team he loved everyone in the room: players, coaches, all of them.

In a quiet moment after the uplifting loss, I ask Sanders what America could learn from it. “Everything about us is designed and built to go forward,” he says. “I’ve never been a rock, an idle person. I’ve always been a mover and a shaker, a wave maker and a go-getter.” He shares one more message before heading back to the recruiting lounge. “We coming,” Sanders says. “You’ve got to be crazy if you can’t see that. We coming.” —With reporting by Leslie Dickstein, Simmone Shah, and Julia Zorthian

Styling by Casey Trudeau; make-up by Beth Walker; grooming by Dermonico Townsend