Michael Cohen once believed he would lead Donald Trump’s presidential campaign.

When that didn’t come to pass, he told friends he might be White House chief of staff. That didn’t happen either, but still he swore he’d “take a bullet” for Trump. In the end, the President’s longtime personal lawyer stood before a federal judge in a New York City courthouse on Aug. 21 and swore to something else entirely: that he had engaged in a crime coordinated by the man who now sits in the Oval Office.

Even in a presidency punctuated by surreal moments, it was a stunning scene. Cohen pleaded guilty to eight felony counts, including arranging payments during the 2016 campaign to suppress two women’s accounts of alleged extramarital affairs with Trump. “I participated in this conduct,” Cohen avowed, “in coordination with and at the direction of” Trump himself. With that extraordinary statement, he implicated the President of the United States in a federal crime–to be violating campaign-finance laws–the “principal purpose,” of which he said, was to influence an election that Trump won by only 78,000 votes in three states.

The courtroom drama brought all the President’s legal and political problems together in a single supernova. It highlighted Trump’s sordid history with women, his willingness to blur the lines between business and politics, and growing fallout from the investigation led by special counsel Robert Mueller, who referred the Cohen case to federal prosecutors. Worse, the explosion came minutes after Trump’s onetime campaign chairman Paul Manafort was convicted on eight counts of tax evasion and bank fraud in a case prosecuted by Mueller’s deputies. And it followed revelations that White House counsel Don McGahn has cooperated extensively with Mueller’s probe, sitting for more than 30 hours of detailed and candid interviews.

It was arguably the most pivotal day in this presidency, and the consequences are only beginning to kick in. Cohen’s plea raised questions that cut to the heart of Trump’s legitimacy. If Trump was willing to deploy his vast fortune to quash salacious stories, as Cohen alleges, what else might he have used his wealth for? What other damaging information could the President’s former fixer share? And what scrutiny awaits Trump’s business empire, which the President has sought to shield from the widening probes?

For now, Trump may not pay a political or legal price. He has benefited from an unshakable bond with his base: even as criminal investigations seep further into his inner circle, Trump has averaged an 87% approval rating from Republicans so far in his second year, according to Gallup. And many legal experts believe that as President he cannot be indicted for a crime while in office. “He did nothing wrong,” said White House spokesperson Sarah Huckabee Sanders on Aug. 22. “There are no charges against him in this. And just because Michael Cohen has made a deal doesn’t mean that that implicates the President on anything.”

There was no question, however, that the late-August events mark a new and dangerous phase for Trump. “For the first time,” says former federal prosecutor David Axelrod, “we’ve seen, in court, evidence strongly linking the President to criminal acts.” That testimony, offered under oath by the President’s former lawyer, will only embolden Mueller and energize Trump’s Democratic opponents. It left West Wing staffers scrambling to soothe their furious boss. And it carried unmistakable echoes of John Dean’s turn against Richard Nixon in 1973, along with the growing sense that a presidency suffused with scandal is confronting its toughest fight yet.

In a fitting twist for a President from New York City, the trouble began with taxis. In addition to his day job as a Trump Organization executive, Cohen dabbled in real estate, medical businesses and even an offshore casino boat. By 2010, according to court documents, Cohen had also bought a portfolio of taxi medallions, the metal placards that allow drivers to operate cabs in cities like New York and Chicago. Cohen leased the medallions to drivers and, according to his plea, failed to report all of the profits to the IRS. In one scheme between 2012 and 2016, Cohen earned more than $2.4 million in interest from loans he made to a taxi operator who leased some of his Chicago medallions. In another, Cohen failed to report $1.3 million in income for a different taxi operator who paid Cohen personally for part of the leases, rather than Cohen’s medallion company. Cohen also didn’t report $100,000 he received for brokering a Florida real estate deal, or a $30,000 fee he charged in 2015 for arranging the sale of a Birkin bag, a high-priced French handbag. In total, he confessed to concealing more than $4 million in personal income.

Suspicion that Cohen had engaged in tax evasion and bank fraud led Mueller to refer the matter to investigators in New York’s Southern District. On April 9, the FBI stormed Cohen’s hotel room, apartment, law office and bank boxes, collecting computers, cell phones, tax records and other materials. The raid was unusual not only because Cohen had been the President’s personal lawyer but also because prosecutors have to get special permission from a judge before raiding a lawyer’s property unannounced to avoid violating attorney-client privilege.

The evidence uncovered led to the Aug. 21 plea deal. Unveiling it, prosecutors released new details about Cohen’s role in arranging payments to two women, former Playboy model Karen McDougal and pornographic actor Stephanie Clifford, who performs under the name Stormy Daniels, to quash embarrassing stories about their alleged liaisons with Trump. In the summer of 2015, according to court documents, David Pecker, a Trump friend and the chairman of American Media Inc., the company that publishes the National Enquirer, told Cohen he would act as something of a fixer for the campaign. Cohen told prosecutors that Pecker agreed to “help deal with negative stories” about Trump’s “relationships with women.” He offered to assist the campaign in “identifying such stories so they could be purchased and their publication avoided,” a practice known in the tabloid industry as “catch and kill.”

In June 2016, a month before Trump became the Republican nominee for President, Pecker alerted Cohen that McDougal had offered to sell the Enquirer the story of her affair with Trump, which allegedly took place shortly after Trump’s wife Melania gave birth to their son Barron, according to court documents. Cohen told prosecutors he urged Pecker to buy the story and promised to reimburse the magazine. Pecker’s company paid McDougal $150,000 for the rights to the story, which the Enquirer never published. The “principal purpose” of the deal, Cohen told prosecutors, was to suppress the story to prevent it from influencing the election. In late July 2018, Cohen’s attorney Lanny Davis released a secret audio recording from September 2016 in which Cohen tells Trump “we’ll have to pay” to purchase the rights to McDougal’s story. Trump responds, “Pay with cash.”

Around Oct. 8, 2016, an agent for Clifford approached an editor at American Media about telling the story of her own alleged affair with Trump. It was the day after the release of the bombshell videotape of Trump on the Access Hollywood set, bragging to “purchase [her] silence,” according to Cohen’s plea.

When Cohen failed to pay Clifford immediately, Clifford’s then attorney told the editor that she would take her story to another publication. The editor texted Cohen, according to court documents, telling him, we “have to coordinate something … or it could look awfully bad for everyone.” Two days later, Cohen wired $130,000 to Clifford’s attorney, and Clifford signed a nondisclosure agreement, according to the court documents.

Cohen was reimbursed for his payment to Clifford by the Trump Organization in monthly installments of $35,000, the court records show. The Trump Organization itemized the invoices as legal services, even though Cohen had not provided any, according to the plea.

All this end ran federal laws barring campaign contributions of more than $2,700 by an individual or any amount by a corporation. Legal experts say that if Trump had paid Cohen out of his own bank account, it would not have been a violation of campaign-finance law. “It’s because he chose to use the corporate coffers to reimburse Cohen that you get this additional violation of federal law by the Trump Organization, and by extension Donald Trump himself,” says Paul S. Ryan, vice president of policy and litigation at Common Cause, a nonpartisan organization that filed complaints with the Department of Justice and the Federal Election Commission earlier this year regarding the campaign’s payments to Clifford and American Media.

If anyone imagined that these sordid details didn’t add up to serious legal jeopardy for Trump, the top law-enforcement officials on the case set them straight after the Aug. 21 hearing. As the U.S. prosecutor on the case, Robert Khuzami, said, “We are a nation of laws, with one set of rules that applies equally to everyone.” William F. Sweeney Jr., the FBI’s top New York cop, chimed in that “we are all expected to follow the rule of law.” And James Robnett, the special agent in charge of the IRS’s New York Criminal Investigation unit said Cohen’s plea “sends a clear message that the tax laws apply to everybody.”

And the transactions open up problems for the President that go beyond his implication in a federal crime. By confessing that he invoiced the Trump Organization, Cohen may draw increased scrutiny to the company’s books. That could result in the closest look yet at the finances of a President who has steadfastly refused to release his tax returns.

Already, some Trump antagonists have seized on Cohen’s statements as supporting evidence in their own ongoing legal battles. “The likelihood of me being able to depose Michael Cohen and the President of the United States just went up exponentially,” says Michael Avenatti, Clifford’s attorney, whose motion to take testimony from both men awaits a hearing. A California judge had stayed the case pending the outcome of the Cohen investigation. A hearing on whether to lift the stay is scheduled for Sept. 10 in Los Angeles.

All this would be worrisome enough for the President if his problems ended with Cohen. But they don’t. In the same hour the lawyer pleaded guilty to eight felonies in Manhattan, Manafort was facing the music in a courtroom outside Washington. His conviction on eight criminal charges–two counts of bank fraud, five counts of tax fraud and one count of failing to disclose foreign bank accounts–illustrates the depth and breadth Mueller’s investigation. That probe has already resulted in more than 100 criminal charges against 33 people and three companies and secured guilty pleas from Manafort’s longtime deputy Rick Gates, former Trump National Security Adviser Michael Flynn and former Trump campaign aide George Papadopoulos.

During the Manafort trial, federal prosecutors did not address possible collusion between Trump’s presidential campaign and Russian actors, but they did show that Mueller’s investigators are looking closely at potential financial crimes. The Mueller probe reportedly has ensnared top Trump associates like Roger Stone over what he knew about WikiLeaks’ release of emails stolen from the Hillary Clinton campaign chairman’s account. Mueller is reportedly also looking at the President’s eldest son, Donald Trump Jr., for his role in a secret meeting during the 2016 campaign with a Russian lawyer, billed to the campaign as an opportunity to gain damaging information on Clinton. Cohen has reportedly said he is willing to tell Mueller that Trump was aware of the June 2016 meeting in Trump Tower before it happened.

Trump’s most immediate peril may not be on the legal front. Justice Department guidelines restrict prosecutors from bringing charges against a sitting President–he can be indicted only after he leaves office. But the political toll of the mushrooming scandals is another matter. In the short term, he is unlikely to see his support drop. “This won’t be a blip in polls,” a top Democratic Senate aide predicted. “Literally, nothing changes this guy’s polling.” Most Americans have fixed their opinions about him by now. “This stopped being a game of persuasion in about October of 2016,” a top Republican on Capitol Hill said.

But the courtroom drama cemented corruption as a theme that Democrats will use to hammer Republicans in the 11 weeks until the midterm elections. Democrats are wary for now of the argument that Cohen’s claims should initiate impeachment proceedings, fearing the prospect would energize Trump’s supporters more than their own. Some of the most successful messaging tests Democrats have seen, according to two top strategists who have conducted focus groups in representative districts, is to cast incumbent Republicans as “yes men” to the President. That’s why strategists close to House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi recently sent a memo to Democratic candidates with a proposed message: run as a check on Trump’s agenda. In their research, pollsters found that Democratic candidates saw a 12-point bump using that message; among independent and nonaligned voters, the rhetoric was worth 14 percentage points.

If Trump’s spreading scandals engulf Republicans in November, Democrats could find themselves chairing committees next January with broad powers to investigate the President and his associates. A Democratic House or Senate could challenge the White House on everything from the President’s coveted border wall to his tax returns. Washington would tilt on its axis as Democrats with subpoena power move against their beleaguered opponent in the White House.

Which is why Cohen’s courtroom turn could be the start of a consequential, even historic, period in American politics. More details of his allegations against Trump will surely emerge. A second Manafort trial on charges he acted as an unregistered foreign agent will get under way in September. And eventually Mueller will likely issue a report detailing everything he has found about Russia’s 2016 meddling and whether the Trump campaign was involved. At which point Democrats who might control one or both chambers on Capitol Hill could be expected to look beyond their own investigations to impeachment.

With reporting by Alana Abramson, Haley Sweetland Edwards and Kate Reilly/New York; Molly Ball, Ryan Teague Beckwith, Philip Elliott and Abby Vesoulis/Washington

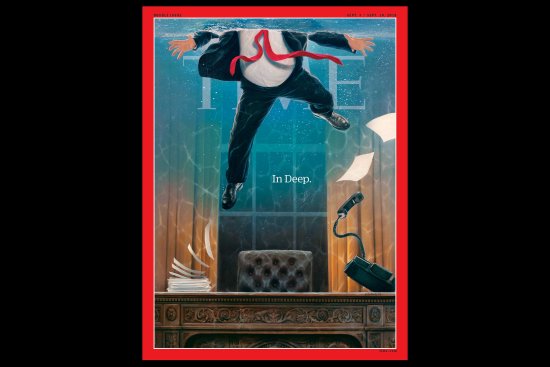

This appears in the September 03, 2018 issue of TIME.

Correction: The original version of this story misstated the limit on campaign contributions by an individual in a federal election. The limit is $2,700, not $27,000.