Prime Minister Fumio Kishida wants to remake Japan as a global leader and military power.

The official residence of Japan’s Prime Minister is a spooky place. Inspired by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, the stone and brick mansion in central Tokyo had been around for only three years when young naval officers charged in and assassinated Prime Minister Tsuyoshi Inukai in 1932. Four years later, Prime Minister Keisuke Okada was forced to hide in a closet during another attempted coup d’état, which killed five and left bullet holes that still pepper the building’s Art Deco facade.

The bad energy became transpacific when, in 1992, U.S. President George H.W. Bush became ill during a banquet here, vomiting onto the lap of Prime Minister Kiichi Miyazawa before passing out. Despite a reported exorcism by Shinto priests, an association with malevolent spirits was sealed, and the residence went unoccupied for nine years until Prime Minister Fumio Kishida moved in soon after taking power in October 2021.

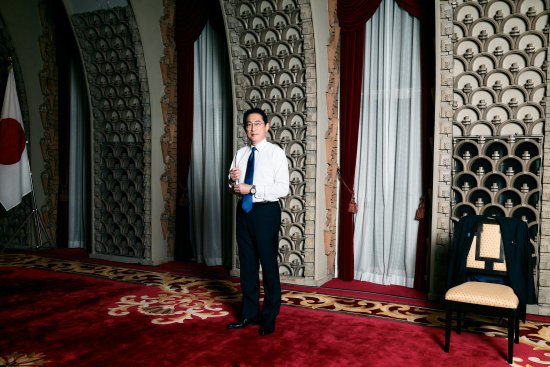

“I have been warned by my predecessors that you will encounter ghosts in this building,” Kishida, 65, tells TIME in an exclusive interview inside the red-carpeted residence, gazing around at the expressionist wall motifs, which include at least one rather menacing concrete gargoyle. “Of course, it is an old building, so I hear sounds from time to time. But fortunately, I have yet to encounter a ghost.”

Buy a print of the Fumio Kishida cover here

Kishida is preoccupied by more earthly issues. In Japan, he has launched a “new model of capitalism” to grow the middle class through redistributive policies. Overseas, he has set about revolutionizing the East Asian nation’s foreign relations: soothing historical grievances with South Korea, strengthening security alliances with the U.S. and others, and boosting defense spending by over 50%. Buoyed by a White House eager for influential partners to check China’s growing clout, Kishida has set about turning the world’s No. 3 economy back into a global power with a military presence to match.

But that’s not to say Kishida is untroubled by ghosts. His family hails from Japan’s southern city of Hiroshima, which he still represents as a lawmaker, and he lost several relatives to the atomic bomb dropped by the U.S. in 1945. His earliest memories include sitting on his grandmother’s knee in the beleaguered city and hearing horrific tales of local suffering. “The unspeakable devastation experienced by Hiroshima and its people was inscribed vividly in my memory,” he says. “This childhood experience has been a major driver of my pursuit … of a world without nuclear weapons.”

Read More: After the Bomb: Survivors of the Atomic Blasts in Hiroshima and Nagasaki Share Their Stories

It’s to Hiroshima that Kishida welcomes leaders of the G7 from May 19 to 21, when he’ll hope to leverage the city’s tragic history to convince the world’s most powerful democracies that only collective resolve can face down the authoritarian threat of an increasingly belligerent Russia, China, and North Korea. Tokyo may be 5,000 miles from Kyiv, but the war in Ukraine has alerted Japan to a more perilous world, not least since Japan remains entangled in land and sea territorial disputes with Russia, and regularly sees North Korean ballistic missiles flying overhead. Even more worrisome for Japan has been China’s aggression against Taiwan, the self-ruling island that authoritarian President Xi Jinping has repeatedly vowed to bring to heel. When Beijing launched military drills last summer to protest U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taipei, five missiles fell into the waters of Japan’s Exclusive Economic Zone, through which Chinese naval vessels and aircraft regularly intrude.

Against this backdrop, Kishida in December unveiled Japan’s biggest military buildup since World War II, mirroring upticks in defense spending across Europe, including Germany, which like Japan was humbled by that war. The commitment would raise defense spending to 2% of GDP by 2027, giving Japan the world’s third largest defense budget. And while previous Japanese leaders dithered over imposing international sanctions, Kishida has joined U.S.-led measures with alacrity.

It’s a transformation that had long been touted by Japan’s former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who belonged to the same right-leaning Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and was assassinated during a campaign stop in July. But while Abe’s hawkish reputation was divisive, Kishida’s dovish persona has enabled him to enact security reform without significant pushback.

Still, Japan’s martial resurgence isn’t without controversy. The nation has a pacifist constitution, and critics say its military buildup pours fuel on an already combustive regional security picture. And given that China is Japan’s top trading partner, it’s unclear how Kishida can fund an ambitious domestic agenda while turning the screws on America’s superpower rival, which has proved all too willing to mete out economic retribution. More fundamentally, some believe that Japan’s rearmament chafes with Kishida’s longstanding pledges to work toward a nuclear-free world. The Prime Minister, for his part, says his only goal is to prevent tragedies like Hiroshima unfolding once again: “Today’s Ukraine could be tomorrow’s East Asia.”

Kishida’s tenure has already encountered drama that belies his reputation as a bland functionary. On April 15, Kishida narrowly avoided joining the ghosts stalking the Prime Minister’s residence when a homemade pipe bomb was hurled at him during a campaign speech, injuring a policeman. “I am living in the world of politics,” he shrugs when asked about the incident. “All sorts of events and developments could happen.”

When he took office 18 months ago, he was thought of as a steady but uninspiring politician, unscarred by scandal but lacking major accomplishments. His father and grandfather were both lawmakers, and he spent part of his childhood in the U.S., attending a public school in Queens. Classes were filled with children of myriad cultural and linguistic backgrounds, and Kishida says he found communication “very challenging.” But because of this, “I was reminded of the importance of listening carefully to the views of others,” he says. “As a child, I was inspired by what makes America the United States, which is respect for freedom and an abundance of energy.”

Kishida was an average student, failing his law school entrance exam three times. After cutting his teeth in banking, Kishida entered politics in 1993. He rose to various cabinet posts and was appointed Minister for Foreign Affairs in 2012, serving in the position for five years, a Japanese record. He forged a reputation as a consensus builder, coordinating policy in back rooms by deliberating with various factions. Aides say Kishida takes advice, but once his mind is made up, he doesn’t waver.

As Prime Minister, he’s proved himself a prodigious worker. Kishida has made a dizzying 16 overseas trips since taking office. The day after he sat down with TIME inside his official residence’s vaulted Great Hall, he departed for a four-nation tour of Africa. Aides say he’s barely managed to take any time for himself. “After the [parliamentary] session is over, if some time remains, I hope I will be able to play some golf,” he says with a grin.

But it has not all been smooth on the domestic front. Kishida’s approval ratings plummeted following a backlash to his decision to hold a state funeral for Abe, over both the expense and Abe’s polarizing character. Late last year, Kishida fired four cabinet ministers in two months over a variety of scandals. In February, he dismissed a close aide for saying “quite a few people would abandon this country” if same-sex marriage were legalized, despite a majority of the population’s supporting it. In response, Kishida tells TIME that he is committed to “realizing a society where diversity is respected.” Kishida’s approval rating has since picked up, and his LDP won key seats in local elections in April.

Read More: What Asia’s LGBTQ+ Movement Can Learn From Japan

“He may not be an inspiring leader,” says Jeff Kingston, director of Asian studies at Tokyo’s Temple University. “But he has proven to be fairly effective in terms of promoting his agenda.”

It’s an ambitious one. Japan has the world’s second most educated population and boasts its longest life expectancy, lowest murder rate, little unemployment, and unusually smooth political transitions. But it also has one of the world’s lowest birth rates, stagnated growth, and a severely aging population. In the late 1980s, Japanese people earned more than Americans. Now they earn 40% less on average. Kishida’s mission is to drag Japan back up. He has embarked on a sweeping modernization drive, recently green-lighting the nation’s first casino as well as a dedicated autonomous driving lane for the Shin-Tōmei Expressway, a key logistics artery.

Kishida’s domestic agenda rests on a nebulous “income-doubling plan” to boost household earnings, but his big problem is how to pay for redistribution without alienating the affluent. Japan’s ratio of public debt to GDP stands at 256%—about double that of the U.S.—and Kishida has little wiggle room to keep borrowing. When he floated the idea of raising taxes on stock transfers and dividends, Japan’s bourses tanked. “Mr. Kishida has to be pretty careful to keep key right-wing support,” says Mieko Nakabayashi, a professor at Tokyo’s Waseda University and a former Japanese lawmaker.

Kishida also wants to get more women and seniors into gainful employment. Japan ranked 116th among 146 countries—the lowest of developed economies—in the World Economic Forum’s 2022 gender-gap report. But while Kishida’s government has set targets to reach 30% female executives at big firms by 2030, “I don’t think it has clearly stated what kind of action plan it will actually take to achieve the goal,” says Makiko Ono, CEO of Suntory Beverages & Food, Japan’s most valuable company with a female boss.

Read More: Makiko Ono Has a Plan to Get More Women Into C-Suites

Ultimately, Japan remains over 30% less productive than the U.S. Kishida has charged Japan’s Digital Agency to cut red tape and boost efficiency. Digital Minister Taro Kono tells TIME that he’s discovered 9,000 government regulations that still require handling via antiquated technology, such as faxes, floppy disks, and the hanko—an iconic carved stamp that is obligatory for many official documents.

But Kono has only 800 officials to serve Japan’s population of 125 million, complaining that his agency is “desperately understaffed.” It’s a monumental challenge; embracing the Fourth Industrial Revolution is crucial for developed societies everywhere, though perhaps none more so than Japan, whose shrinking, aging population has “no precedent in the world,” says Kishida. “This is a matter of survival.”

It’s a different kind of existential threat that will occupy the G7 in Hiroshima, where posters promoting the summit adorn billboards and vending machines across the city, with countdown clocks inside the cavernous main railway station. Denied a seat on the U.N. Security Council, Japan has always placed great emphasis on the economic grouping, where it is the only Asian member. Close aides to Kishida say that welcoming the G7 to his home city will be the realization of “a lifelong dream.” Not only is it Kishida’s best chance to catapult Japan to true global leadership, Nakabayashi says he also may use any bounce in domestic approval as a platform to dissolve parliament and seek a fresh mandate.

In January, Kishida made whistlestop visits to member states Britain, France, Italy, Canada, and the U.S. to drum up support for his agenda. He also invited Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol to attend as observers. The stakes are high. “Given the very sketchy situation in the international order, with Ukraine and Taiwan figuring prominently, the G7 must step up or risk becoming irrelevant,” says Kingston.

But not all agree with the G7’s combative posture. Setsuko Thurlow remembers Aug. 6, 1945, clearly. She was just 13 when she was recruited to help decipher intercepted Allied communications as part of Japan’s World War II efforts. At 8:15 a.m., she glimpsed a bluish-white flash through the window of the wooden building that served as the military headquarters in what today is Hiroshima’s Higashi suburb. The bomb detonated at a temperature of 7,700°C just over a mile away.

“I had the sensation of flying up and floating in the air,” she says. After she crawled out from beneath the charred timber, “I started seeing moving figures like people, but not really human beings,” recalls Thurlow, 91, who accepted a Nobel Peace Prize in 2017 on behalf of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons. “They looked like ghosts.”

Read More: A Fire In the Sky: A Schoolboy’s Eyewitness Account of Hiroshima

The bombings of Hiroshima and, three days later, Nagasaki claimed some 170,000 lives. Japan’s more aggressive military posture under Kishida makes Thurlow “alarmed,” she says. “[Kishida] said his top priority was to work toward a world free of nuclear weapons. But right now, I realize he was deceiving us.”

Kishida tells TIME he’s committed to global denuclearization and his government “will not discuss nuclear armament.” And no doubt G7 attendees will have poignant tours of Hiroshima’s Peace Museum and A-Bomb Dome, which was one of the few buildings left standing after the blast, remaining today a rubble-strewn shell of broken bricks and twisted iron girders, rimmed by a neat hedge of flowering azalea.

Kishida draws a straight line between Hiroshima and the stricken Ukrainian city of Bucha, which he visited in March, speaking of “great anger at the atrocity” in a departure from his trademark equanimity. He wants the G7 to know the true horror lurking within Vladimir Putin’s repeated threats of nuclear war, which “came as a huge shock to me,” he says.

Read More: She’s Spent a Decade Fighting to Ban Nuclear Weapons. The Stakes Are Only Getting Higher

Still, it would be disingenuous to pretend that Russia is Kishida’s sole focus. His intention is also to convey that, just as Ukraine is Asia’s problem, Taiwan is Europe’s—rebutting the sentiments of French President Emmanuel Macron, who when asked about Taiwan in April said that Europe must not get “caught up in crises that are not ours.” For Kishida, “Russian aggression against Ukraine is not a development that happened far away,” he says. “Attempts to unilaterally change the status quo by force, wherever they may happen in the world, cannot be allowed.”

Kishida is diplomatic when asked about China’s challenge, citing the need to build on the “positive momentum” forged by his November summit with Xi. However, he admits “China’s current external posture and military trends are matters of serious concern.”

Others in his administration are bolder. Rather than Russia or North Korea, “the major threat is coming from China,” says Kono, who previously served as both Japan’s Foreign Minister and Defense Minister. “We need to be prepared for their military actions as well as economic coercion against Taiwan or others.”

Washington agrees. In recent months, President Biden has committed to enhanced military cooperation with Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, and Australia. He will be pressuring Kishida to assist not only with defense matters but also to prevent technology transfer to China.

Meanwhile, Beijing has set about courting the Global South with a new forum for international relations, which the nation’s state media has dubbed “Xivilization.” It’s a clash of worldviews that promises to keep heating up. Kishida’s mission at Hiroshima will be to keep focus on the city’s charred remains and paper cranes. To let the ghosts have their say.