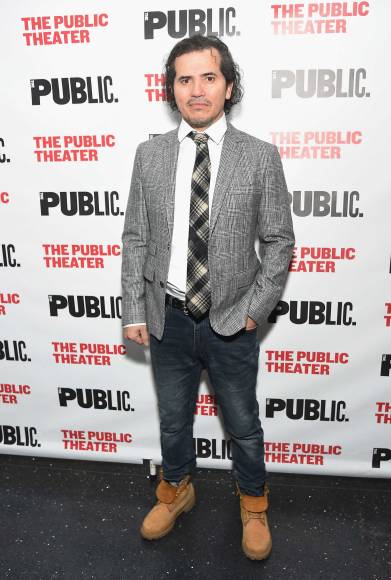

John Leguizamo has a recurring bit in Latin History for Morons, the one-man show he's performing through April 28 at New York City's Public Theater. Anytime he's insulted by another character--played, as they all are, by Leguizamo--he stands on tiptoe, puffs up his chest like a threatened grizzly and demands, "Do you know me, man?" It's a memorable refrain, but it's a red herring. The show only exists because of Leguizamo's realization, a few years back, that he didn't know himself.

Although Leguizamo, 52, is well-known for movie roles like Benny Blanco from the Bronx in Carlito's Way and Tybalt in Baz Luhrmann's Romeo + Juliet, Latin History is his sixth one-man play. It's a primer on the history of people of Latin descent in the Americas, flavored by the performer's raunchy humor, dance moves and spirited impressions, which range from his therapist to the Aztec emperor Moctezuma II. But it's also a comedic lament for the pain of knowing how his people's contributions have been minimized throughout American history.

"If I would have read in a textbook as a kid that 10,000 [Hispanics] participated in the Civil War and Cuban women in Virginia sold their jewelry to feed the patriots," he says, "people wouldn't feel so confident to disrespect me. I wouldn't feel as victimized, because I would go, Well, no! This is my country too."

Born in Bogotá and raised in New York City, Leguizamo felt scorned from an early age. "I had a lot of encounters with bullies, sometimes being the only Latin person in the neighborhood," he recalls. "People always said, 'Why don't you go back to your country? What have your people ever done?'" As a defense mechanism, he developed the sense of humor that would propel his interest in theater.

But when he tried to break into film and TV in the mid-1980s, he faced limited options. "I went to college. I'm an educated man," he remembers thinking. "And all I can play are drug dealers, killers, servants?" Facing a choice between negative representations or none at all, he decided on a third path, creating his own roles. When he staged his first play, Mambo Mouth, in 1990, to 70 spectators in folding chairs, he found an audience willing to listen. And not just any audience: among the crowd was one of his favorite playwrights, Arthur Miller. Leguizamo had found a stage where he might be taken seriously.

Even as his opportunities onscreen expanded--he played a bohemian artist in Moulin Rouge! and voiced a lisping sloth in the Ice Age franchise--Leguizamo kept returning to the theater. The idea for Latin History came from his son, who in middle school began to experience the same bullying his father once had. The play interweaves Leguizamo's lessons on pre-Columbian culture and Hispanic military heroes with his own quest to figure out how best to parent his child. Between those emotional moments and spontaneous eruptions into dance--samba, mambo, even an Irish jig--he keeps the theater from ever feeling like a classroom.

The show is more than a rejoinder to bullies past and present. It's part of a body of work that responds to an industry that once told Leguizamo he could only play dangerous characters--an industry that has changed, he says, but "not quick enough, not big enough." Three decades later, he sees power in his stories. "I'm writing this for me, because this is how I take care of myself, with how invisible we Latin people are in the media," he says. But soon after he begins to write, another question emerges: "Who else is like me who is going to feel the same kind of healing from seeing Latin stories told?"

Those stories feel more urgent than ever to Leguizamo, who says that between recent headlines about deportations and President Trump's rhetoric about Latinos on the campaign trail last year, "my show has much more bite."

In the end, his research became more than fodder for a play. "I feel so empowered now that I know my history," he says. "I've got facts, I've got numbers, I've got proof."