Voices from Democratic Counties Where Trump Won Big

BY ELIZABETH DIAS, HALEY SWEETLAND EDWARDS AND KARL VICK

Among Donald Trump’s supporters, the real estate mogul’s victory was akin to a revolution, a mandate delivered en masse by working class voters sidelined in the modern economy.

“On Election Night, I couldn’t believe it was happening. I was up late watching every state go Trump and I was baffled,” said Sue Stavish-O’Boyle, a long-time Democrat from Forty Fort, Pennsylvania who voted enthusiastically for Trump. “I thought, wow, I can’t believe it! The little people have a voice!”

There was a lot of that. Trump’s victory was no less shocking to the 65.3 million who voted for Hillary Clinton. And the problem was not only that pollsters and pundits failed to foresee that former Democrats like Stavish-O’Boyle in the Rust Belt would flip to Trump. It was that many Clinton supporters simply didn’t know anyone personally voted for the man. And vice versa. The country is not only divided, it is separated. For decades, researchers pointed out that shifting demographics—including the tendency among those with advanced degrees to move away from where they grew up—our communities have grown more ideologically homogenous. More and more, we live among people who vote like we do. According to the most recent election data, nearly half of us—48%—reside in what’s known as “landslide county,” where 60% or more of the population votes for the same candidate. In 1976, that number was 27%, according to Bill Bishop and Robert Cushing, the authors of the 2008 book, The Big Sort: Why the Clustering of Like-Minded America Is Tearing Us Apart.

This kind of ideological segregation gives rise to the kind of comedic, if perhaps apocryphal, remark by New Yorker writer Pauline Kael after the 1972 election: “I can’t believe Nixon won. I don’t know anyone who voted for him.” You heard the same from Londoners after the Brexit vote, which was carried by the countryside. The self-sorting makes common ground harder to find — Clinton dismissing Trump’s base as a “basket of deplorables,” for instance — and caricature and tribalism to creep into a pluralistic republic. The risk is seeing fellow Americans as The Other.

To add texture to demographic generalities—non-college educated whites versus minorities, rural versus urban—TIME sent three correspondents to five counties scattered across Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania. They looked at counties that had voted for President Obama in 2008 and 2012 and flipped for Trump in 2016, but the individuals interviewed were met at random: A correctional officer waiting at an auto body shop; a young women off to pick up her kids at the school bus; a guy operating a table saw in his front yard.

The result is a pastiche of American voices. Some were incorporated in TIME’s special Dec. 19 issue. Others are sampled here, a handful of real Americans, Democrats and Republicans alike, who cast a vote for the candidate who, in victory, became TIME’s Person of the Year for 2016.

Naomi Hines, 26, Owosso, Mich.

A baker at a Meijer grocery store, Hines is a local member of the United Food and Commercial Workers Union Local 951, which endorsed Clinton. But instead of following the union’s lead, Hines put Trump/Pence decals on her car—and when her mother, a Democrat, peeled them off in protest, put twice as many back on. “You weren’t brought into this world to rely on Ms. Suzy down the street to pay for you,” she says of her vote for Trump. “That was what my grandfather instilled in me, and he was a Democrat.”

Hines has decided to join the Shiawassee GOP executive committee to be involved in the Republican future, for herself and her two-year-old son. Of all Trump’s proposals, she says, the wall along the U.S.’s border with Mexico is the least appealing. “But let’s secure the border,” she adds. “Yes lets still help others, but lets take care of home first.”

Ron Seippel, 57, Beetown, WI

“This is a rebellious part of the state, as they say in Madison,” says the farmer, of Wisconsin’s hilly southwest. “They always refer to Madison as 56 square miles of fantasy surrounded by reality.”

Seippel says he suffered through the presidential derby. “I voted Democrat for the last 25 years, but I voted for Trump,” he reports. The ballot was cast “more against her, because I would have voted for somebody less liberal.” He names Jim Webb, the former Marine and U.S. Senator from Virginia, as an acceptable Democrat. “I’d have voted for him in a heartbeat.”

“If she’d been more moderate she would’ve won,” Seippel says, at the bar of the Yesterdaze tavern, where the locals are preparing for the first day of deer season. “Like the border. People want that border secured. Working people do.”

Shannon Goodin, 24, Owosso, Mich.

A first-time voter who doesn’t consider herself a Democrat or a Republican, Goodin says Obama was “really likable” but Trump earned her support by being “a big poster child for change.” “Politicians don’t appeal to us,” Goodin says of why Trump earned her trust. “Clinton would go out of her way to appeal to minorities, immigrants, but she didn’t really for everyday Americans.”

A hairstylist, Goodin recalls one day when two clients pulled their business after she posted online that she hoped Michigan would turn red. But supporting Trump is about jobs and the economy, not social issues. With any change, she says, “it is normal to be a little scared, but I’m excited.”

Moses Sam, 25, Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania

With tattoos and the kind of thick-framed glasses that would pass muster in Brooklyn, Sam doesn’t fit the typical Trump supporter stereotype. Like many Americans, his heritage is a grab bag—he’s got Lebanese-Coptic, Italian, Puerto Rican, and Portuguese roots—but he rejects what he sees as exclusionary identity politics. “I’m just an American,” he says.

Sam, who pieces together full-time work as a bouncer at a nightclub and waiter at an upscale bistro, says the Democratic Party no longer represents working Americans like him. “Urban liberals and social justice warriors and the media all began pandering to subsets of people,” he says. That doesn’t mean he’s bigoted, racist or close-minded, he says, noting that his adoptive brother is gay. “I don’t have any problem with anything like that. Everyone’s just people,” he says. “I just don’t think it helps anything when we think of ourselves as different.” Sam, who sold drugs, has a felony record and is currently on probation, says his politics are based in the belief that “liberty survives better in a capitalist, nationalist government,” he says. “That’s Trump.”

Casey Voss, 36, Owosso, Mich.

When Voss was 19, she started her own hair salon with her best friend. “It makes me really sad how we define the people who understand the changing in the nation are those went to college and make a certain amount of money and look a certain way, because America is the melting pot of all people,” she says. “I got where I am today because of the idea that anything is possible, that you can be a girl who barely made it through high school and you can own your dream business.”

Now, the mother of three and small business owner says the change she wanted when she voted for Obama in 2008 is what she hopes Trump will bring. “I’m scared about every dollar that comes into my business. I’m scared about what that means in Obamacare, in taxes,” she says. “Every single thing happening to me is out of my control.”

Voss keeps a picture of Jesus at her station. Trump is not America’s savior, she says, but she is hopeful for the future. “Just like in marriage or in a business partnership, I made a choice,” she says. “He’s going to fight so much harder now that everyone is against him.”

Ashlyn Boyd 22, Perry, Mich.

A lot of Boyd’s friends don’t know she voted for Trump. Most supported Clinton, she says. But Boyd, who went to cosmetology school during high school, had other concerns. Obamacare looked good on paper but was unaffordable for her family. Her three-year-old son will soon be in school, and she opposes Common Core. She thinks Trump’s idea of term limits is an “amazing thing,” and she likes the idea of tariffs on companies in America that send out their products for cheaper labor. “I don’t think all people who voted for Hillary are liberal snobs. I am 100% for gay marriage. That is not why I voted for Trump,” she says. And, she adds, “it is awesome that a woman successfully ran Trump’s campaign.”

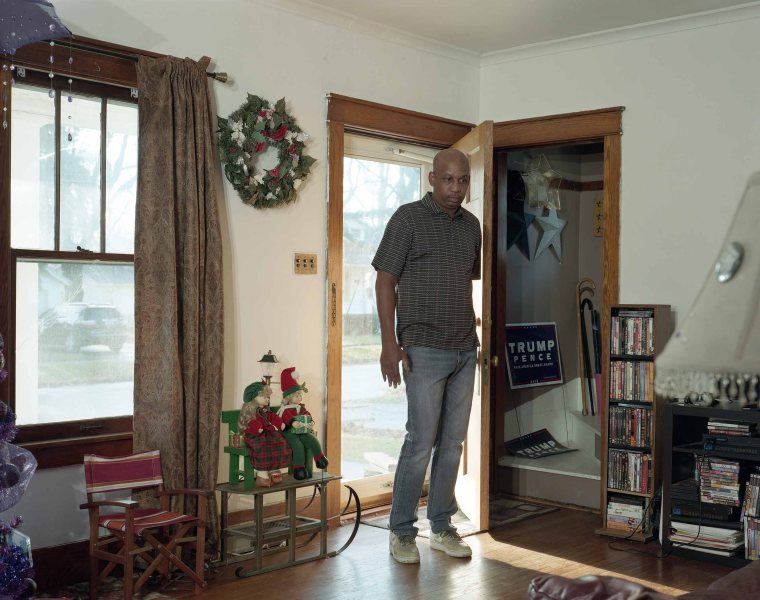

Darryl Wimbley, 48, Saginaw, Mich.

After two decades as a car salesman, Wimbley hopes he will soon be able to franchise his hot dog stand business. This year was the first time he voted for a Republican for the White House. Looking back, he thinks his 2008 vote for Obama was “the most racist thing I ever did, I voted for him simply because he was black,” he says. “America is a business, it is not a soup kitchen,” he says, explaining his support for Trump. “I have made a lot of money for other people. It is time I make it for myself.”

Wimbley says his decision has come with a high cost from other black members of his community. “I’m dubbed a ‘coon,’ an ‘Uncle Tom,’ I should be killed, my babies should be killed,” he says. “These are people who say they are social justice warriors. They are saying the Constitution only applies to them.”

Brittany Bucholtz, 26, Dallas, Pennsylvania

The certified nursing assistant and mother of two is usually too busy for politics: 2016 is the first time she showed up to vote. What got her to the polls this time around, she says, is partly her disappointment with President Obama, whose message she liked in 2008. “He was all for the working class, but when he got in, it was all for the upper class,” she says. She’s also disappointed with where she sees the country going. “There’s no more middle class,” she says, “There’s poor or there’s rich and there’s nothing in between.” Of all the women she works with, only one supported Hillary Clinton, she says. All the rest of us were Trump supporters. “He’s the one who’s speaking to us,” she said. “He would come and do these rallies or you’d hear him on TV and he’d just say all the things we wanted to say.”

Kim Woodrosky, 53, Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania

“Going way back when, if you were in a union, if you were a working class person, you were a Democrat,” says the real estate investor, whose father was a Teamster and whose mother worked in a textile mill. “That’s just the way the ball fell.” But in 2016, Woodrosky says she couldn’t “bring herself” to vote for Clinton, who she saw as compromised and untrustworthy—even if it meant foregoing an opportunity to shatter a glass ceiling. “I want a woman president. I want to see a woman president. I’m a woman. Why wouldn’t I?” she says. “ But she was not the one I wanted to see.”

“Honestly, the one thing she said that stuck in my head was, ‘If you were happy with the last eight years, vote for me and we’ll continue that,’” Woodrosky said, and then laughed out loud. “Well, I wasn’t happy with the last eight years, so she was also telling her not to vote for her!”

Sandy Lewis, 56, Swoyersville, PA

A self-described “life-long Democrat,” Lewis works at the county welfare office and fiercely defends those who find themselves with no other choice but to depend on food stamps and state housing assistance. Recently, she started learning sign language with an eye toward helping people who are deaf access what they need in the community. Lewis’ son, Tom Curry, who died of cancer in 2007, was the president and founder of the Luzerne County Young Democrats and represented his neighbors in the state’s Democratic Party.

Lewis voted for Trump in November in part because she couldn’t bring herself to cast a vote for Clinton and in part because she believed the New York businessman is the best choice to “shake up” Washington. “I was raised a Democrat, pure Democrat. I’m still a Democrat,” she says, before pausing to collect her thoughts. “Do I feel like a traitor? A little bit. But you know, if my son was here he would say, ‘Mom, you did the right thing.’”

Brandon DeFrain, 33, Pinconning, MI

DeFrain, the chairman of the Bay County Republican Party, is an operations manager for Home Depot. When teachers and union workers started asking him for Trump signs, he knew Trump would flip the county Obama won twice. “We were available, we listened to people,” he says of his team’s efforts. “Obama had the opportunity to be the greatest president in the history of the world. I don’t think he did a good job uniting the country on day one….We wanted a change from the change.”

Trump’s business losses and ability to recover also only made him a more appealing candidate for a county that witnessed firsthand its economy collapse beneath it. “He’s always admitted failing,” DeFrain says. “He knows the right people to keep us moving forward.” That’s something he thinks the media coverage missed. “It hurt your feelings every time you turned the television on,” he says. “Were they really gauging how we felt?”

Sara Vasquez, 27, Saginaw, Mich.

Vasquez, a political science college student who works part time at Burlington Coat Factory, supported John Kasich in the primaries, but then knocked doors for Trump in the general. Earlier in her life, she worked two or three jobs and for a time relied on food stamps. She remembers her role model, her grandfather who left Mexico to work in Midwestern strawberry fields and died a U.S. citizen who she says owned a million dollar home and his own business. “I’m all for immigration if it is done legally, and for people wanting to live the American dream, like my grandfather did,” she says.

“For things like abortion and gay marriage, even though I consider myself Republican, I think more along the lines of, that’s who you are,” she adds. “I have a cousin who has had three abortions, and gay marriage became legal on my birthday, and I was just as ecstatic about it as anybody else.”

Sue Stavish-O’Boyle, 50, Forty Fort, PA

The licensing specialist at the Mohegan Sun Casino was a Democrat up until January 2016 when she switched her party registration and voted for a Republican in a presidential election for the first time in her life. For her, the decision was clear. She wasn’t only voting against Clinton; she was voting for Trump. “I liked that he wasn’t involved in Washington, he wasn’t a politician. I liked that he was shooting from the hip. I felt like he was going to champion the common people even though he’s a billionaire—I get that. But he’s not part of the bureaucracy. He doesn’t owe anyone anything,” she says. Stavish-O’Boyle, who describes herself as a conservative Democrat, is both pro-gay marriage and pro-life, and feels no kinship with “radicals” on either ends of the ideological spectrum. “I think there’s a lot of us out here,” she says, “who feel the way I do.”

Thomas and Erica McTague, 38 and 33, Plymouth, PA

Thomas, a police officer, and Erica, a hairstylist, appreciated Trump’s stance on law enforcement and immigration, but voted largely on economic issues, like unemployment, underemployment and free trade. That many in their community can’t find reliable jobs that pay enough money support a family is a huge concern. “Go back 60, 70 years and this area had industry and people had good jobs,” he says. “When Trump talked about getting rid of all this free-trade stuff, he brought to life the way this country should be going.”

David Digman, 69, Mt. Hope, WI

A dairy farmer and raconteur, Digman was finishing lunch at Ma’s Bakery and opining on the election even before a reporter made himself known. A newscaster that morning had mentioned Trump’s reliance on “less educated, lower-income, rural voters” and Digman began loudly addressing his lunch companions by that description: “Hank, you’re less educated, lower-income and rural, what do you think?” Digman voted Trump but sees his ample flaws. “I thought he had no chance in hell,” he says. “Sometimes in the debates he was like a 12-year-old. Come up there and box his ears, you know.”

But the farmer — “I figure myself as a middle class redneck” — and the billionaire share much, including an airy approach to international affairs. “Get Russia to nuke China,” Digman says. “That’ll take care of our debt! I was thinkin’ about that one day while I was milkin.”’ He paused and observed. to no one in particular: “I’d love to go Russia to hunt.”

Like many in southwestern Wisconsin, Digman is selling his farm, as the economies of scale drive consolidation across the Dairy State. Also like many, he employs a Mexican as a regular farm hand, and an Amish for odd jobs — they’re excellent workers, and will take less than young locals. “My Mexican workin’ for me, he said, ‘You can’t vote for Trump. He’s gonna send us all back.’ I said, He’ll never find you here in Mt. Hope.” The worker, he says, is “illegal as can be,” which doesn’t bother Digman in the specific, but does in the general. “Oh, we gotta have these Mexicans here,” he says, “but we gotta have ‘em legally.”

Joseph Dougherty, 49, Nanticoke, PA

A lifelong Democrat, the former mayor of Nanticoke became a Republican this year to vote for Trump, who he sees as more representative of “hard-working, blue collar workers looking for family-sustaining jobs.” To Dougherty, the problem lies in part with the Democratic Party, who he believes sidelined their core constituency in the Rust Belt states. “We didn’t leave the Democratic Party. The Democratic Party left us,” he says.

Dougherty says statistics showing an improving economy aren’t reflected in his community, where people are working harder and harder but “getting more and more taken out of their paycheck every month.” “We don’t want to just survive,” he said. “People are tired of surviving. People want to go on vacation, improve their home, get a better car, invest in their children’s future.”

Chris Wilson contributed reporting.