BY SIMON SHUSTER / LONDON

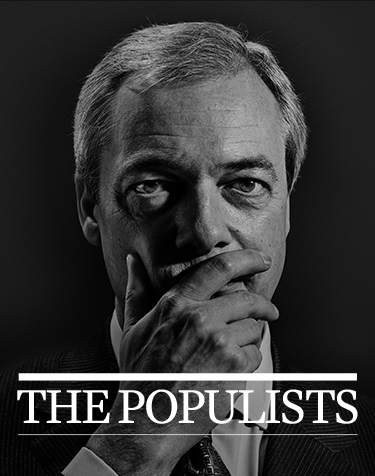

Donald Trump met with his first foreign ally just a few days after winning the U.S. presidency. But it wasn’t one of the world’s leading statesmen who got the invitation to Trump Tower. It was Nigel Farage, a man once considered a footnote in British politics—but who, in 2016, found himself on the snug inside of one of history’s hairpin turns.

As the face of the United Kingdom Independence Party, a right-wing group on the fringe of British politics, Farage campaigned for 17 years for the U.K. to leave the European Union, styling himself as a “middle-class boy from Kent” who was not afraid to tell hard truths about the failures of the European project, from out-of-control immigration to the coddling of radical Islamism. On June 23, British balloters finally granted Farage his wish, voting to leave the E.U. in the stunning Brexit referendum. The result was one that Europe’s pundits, pollsters, bookies and politicians said would never happen. Farage then spent weeks in the U.S. stumping for Trump, who took to calling himself “Mr. Brexit.”

The outsiders won again with Trump’s victory on Nov. 9, and Farage has become a kind of roving ambassador for Trumpism ever since, giving speeches and campaigning for the dawn of a new world order—or at least the destruction of the old one. It’s a movement, a revolt, that is rising throughout Europe, including core E.U. nations like France and Germany. “I’m in no doubt that the European project is finished,” Farage told TIME over a pint of stout in London one chilly afternoon in late November. “It’s just a question of when.”

But even Farage, the 52-year-old soothsayer with the arsonist’s grin, has no clear idea of what to put in place of that establishment. The contours he describes (and apparently longs for) cast Europe as a kind of patchwork, broken down to its constituent nation-states and unbound by what he calls the “false identity” of Europeanness and all its prim ideas of tolerance and multiculturalism. He also has a deep mistrust of institutional power. Real power in the modern day resides, Farage says, ever more “massively” in personalities, not formal titles. What keeps it alive is the charisma of those who possess it, their ability to rally the masses and make deals and connections as expediency dictates. It is a world of horse traders, not bureaucrats.

Given how fast the dominoes are falling in Farage’s direction, that world might soon be upon us, for better or worse. Italy’s populist parties helped swing a referendum result on Dec. 4 that forced Prime Minister Matteo Renzi to resign. The Netherlands and France have crucial elections scheduled next year, and front runners in those countries are tapping the same veins of anger at the establishment that fueled the rebellions of 2016. Marine Le Pen, the leader of the far-right National Front in France, has chosen a blue rose as the logo for her presidential campaign, a symbol, she says, of the freak events that now seem almost natural. “I think the British, with the Brexit, then the Americans, with the election of Donald Trump, did that,” she tells TIME. “They made possible the impossible.”

Not even Germany looks like such a stable pillar of the Western world these days. Angela Merkel, who has served as Chancellor since 2005, plans to run for a fourth term next fall. But her party, like her country, has felt the backlash against slow economic growth and mass migration across Europe. A November poll found that 42% of Germans want a referendum on E.U. membership. After Brexit, that’s more than enough to make TIME’s 2015 Person of the Year and her allies nervous. “What we are seeing is a re-emergence of state egotism and nationalism,” says Norbert Roettgen, a senior lawmaker in Merkel’s center-right party, the Christian Democratic Union. “This is our disease, and it goes right to the foundations of the European idea.”

By voting to leave the E.U., the British people showed that the integration of the West is neither inevitable nor irreversible, a message that Trump’s campaign drove home by calling for the U.S. to pull back from its commitments around the world and to focus on “America first.” It is a world where the international agreements of the past are up for renegotiation and the interests of the nation-state are not bound by an established global order. “None of us conform to any of the rules by which politics is operating,” Farage says. “And people like that!”

Making a New World Order

For more than a generation, the Western elites settled into a consensus on most major issues—from the benefits of free trade and immigration to the need for marriage equality. Their uniformity on these basic questions consigned dissenters to the political fringe—further aggravating the sense of grievance that now threatens the mainstream.

That is what helped Farage, Le Pen and other European populists find an audience in 2016. They wanted Europe to be a mosaic of states instead of an integrated commonwealth with a shared currency and open borders. They wanted, in short, for Europe to look more like it did before the E.U.’s grand experiment, never mind that this experiment was designed to prevent the nations of Europe from engaging in an endless cycle of wars.

“What we’ve tried to do in Europe is go against all the trends globally,” says Farage. “Globally, the world is breaking down into smaller units.” The desire to reverse that trend shows Europe’s “complete lack of understanding of how human beings operate.” In the world of Farage and his allies, people gravitate more toward tribal notions of identity than to lofty principles of integration.

The coming months and years will test that theory. While most European leaders were still scrambling on Nov. 12 to establish contact with Trump, Farage was sitting with the President-elect in his penthouse in midtown Manhattan.

They even posed for a photo together that day, grinning in front of the gilded doors of Trump’s apartment; Farage sent a chill through European capitals when he posted the picture online. Christoph Heusgen, who has served as Merkel’s top foreign policy adviser since 2005, says the image was “very confusing.” Farage does not hold any formal power in Britain and never has. Yet there he was, leapfrogging the line of world leaders desperate to arrange a meeting with America’s President-elect.

Adding insult to injury, Trump’s transition team broke with the tradition of arranging all calls with foreign leaders through the State Department. So the Australian government had to get Trump’s cell-phone number from one of his golfing buddies. Heusgen tells TIME the Germans were forced to seek advice from Henry Kissinger, the German-born former U.S. Secretary of State, who suggested reaching Trump through his son-in-law Jared Kushner. “That has been proven successful,” Heusgen says.

But it’s not exactly comforting. Trump has already risked infuriating China by accepting a call from the leader of Taiwan, which Beijing considers a breakaway province, and his breezy pledge to Pakistan’s Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif to “play any role you want me to play” in future talks left Indian diplomats aghast. So either the incoming U.S. President has no idea how diplomacy works or he doesn’t care for its niceties. Heusgen prefers to believe the former, which at least allows room for a “learning curve,” he says. Farage has a more simplistic answer: “If [Trump] believes in you, if he trusts you, then you’re the man he wants to deal with.”

And sure enough, a week and a half after their meeting in New York City, the President-elect tweeted that “many people” would like to see Farage as London’s new ambassador to the U.S. “He would do a great job!” Trump wrote, as though it had somehow become his job to pick the envoys of foreign nations. The British government was then forced to issue an equally bizarre response, reminding the President-elect that its Washington embassy had “no vacancy.”

Farage found this all rather amusing. “A bolt from the blue!” he says. “I had no idea it was going to happen.” Trump’s tweet came as he was sleeping in Strasbourg, the seat of the European Parliament, and Farage says his phone didn’t stop ringing all night.

“It’s been an amazing year,” he says after draining the rest of his pint. What comes next is far less certain. Putting Brexit into effect has been monstrously difficult, and while the British economy has proved more resilient than expected, growth is still predicted to be slower than if the Brits had opted to remain in the E.U. But as Trump takes power and France ponders whether to put an icon of the far right in the Élysée Palace, the West seems to belong to the populists. Only the brave would bet against them after the year they’ve had. —With reporting by Vivienne Walt/Paris