It was a relentless year for news. For many, the beginning of Donald Trump’s polarizing presidency in January set a tone of heightened tension, but it went beyond that. The wildfires and mass shootings, hurricanes and wars—tragedies and milestones that could happen in any year—felt amplified.

Maybe it was the sheer amount of imagery that emerged—the images we scroll past on Instagram when we wake up and browse before bed, the ones we Like and Love and Sad-Face on Facebook, the ones we flip past in newspapers and magazines and are bombarded with online, on line at the grocery store and on the walls of coffee shops, in restaurants and our own homes.

But if the images made a difference, it wasn’t merely a matter of quantity: 2017 was also a stand-out year for photographs. If the year goes down in history books as some great test of humanity, these 10 pictures will serve as the art of that pivotal moment.

Throughout the year, our photo editors set aside thousands of photographs that stuck out for one reason or another—light or composition, beauty or oddity, surprise or suspense. In recent weeks, we chipped away at the pile until we hit the Top 100, then the Top 10. These pictures were chosen not just for the information they provide and the emotions they evoke, but for their staying power: their ability to not just define the year we leave behind but to inform the one ahead. — Andrew Katz, TIME’s Deputy Director of Multimedia

In the initial aftermath of Hurricane Maria, which made landfall on Sept. 20, it was impossible to reach many parts of the island except by helicopter. Wind gusts up to 145 mph had downed trees and power lines, leaving many of the American island territory’s 3.4 million residents without electricity. From the air I could see the widespread damage: roofs blown off, crops flattened, denuded forests, flooded neighborhoods.

But I felt my aerial photographs were missing the human element. On the way back to the San Juan airport, I asked the pilot to fly along the city beachfront, home to many resort hotels and upscale apartment buildings. It was there that I saw one apartment missing an entire wall.

When I zoomed in, I could see a woman sitting casually by the edge on the 13th floor. I only shot two frames before she started to wave hello. The destructive force of Hurricane Maria may have temporarily changed the landscape of the island, but from what I experienced, it didn’t change the generous and positive spirit of the Puerto Rican people.

Kenyerber Aquino Merchán starved to death when he was 17 months old, at only 8.8 lbs.—the weight of a newborn baby. I met his father, Carlos, as he was picking up Kenyerber’s emaciated body from the hospital morgue in Caracas and followed him home to San Casimiro to photograph the wake.

Despite the country having the largest known oil reserves in the world, hundreds of babies have starved to death in the past two years in Venezuela—a country suffering widespread shortages of affordable food, medicine and infant formula—during the worst economic crisis in its history.

The family struggles to afford enough to eat, and had to borrow money and make sacrifices to be able to bury Kenyerber. They held his wake at a family home, to cut costs, and hired a young mortuary worker to come to the house and prepare Kenyerber’s body for burial. He wiped away blood, and injected the body with embalming chemicals on a well-worn couch in the kitchen—next to a refrigerator with no food inside it. Several young cousins kept trying to peak into the kitchen to watch, and Kenyerber’s aunts had to keep shooing them away.

This photo was taken shortly after the mortuary worker finally took the small gray coffin out for viewing, and as the young cousins were able to see Kenyerber’s body for the first time.

More and more family members arrived later. They came carrying wild flowers from the hillside to place around his coffin, and cut out angel wings from a white government food-ration box—a Venezuelan tradition believed to help the souls of babies reach the heavens. Carlos fell to his knees crying: “How can this be?” He hugged the coffin and spoke softly, as if to comfort his son in death. “Your papá will never see you again.”

After photographing the final act of the Route 91 Harvest country music festival on Oct. 1, I began to edit photos in the media tent when loud pops startled me. A security guard told me he thought it was firecrackers or the sound system malfunctioning. This seemed plausible, so I went back to work. Moments later, loud pops rang out again. This time, concert-goers began to flee.

Instinctively, I picked up my cameras. With the concert lights turned off, it was extremely dark as I photographed people running for cover and some lying still on the ground. About 10 minutes later, back in the tent, the only visible light came from my computer screen. The pictures loading onto my computer were telling of the tragedy that had unfolded. Horror washed over me as I saw the images that I had captured. With trembling hands that made it necessary to hold one hand over the other, guiding the track pad, I frantically edited photos.

As authorities began to secure the area, I was told to leave the grounds. I hurriedly packed my gear and was escorted to the exit.

This photograph was one of the first to be uploaded. The image established the urgency of the situation. The posture of the man encouraging the girls to keep running, and people taking cover amidst all the debris strewn about, illustrated the turmoil.

With the area on lockdown, I hunkered in my car across the street all night. I continued working from my vehicle, as authorities had warned me to stay in place. Others in their cars around me seemed to be in a state of disbelief. Shock.

My phone began to ring with people calling from around the world, including family, friends and colleagues. I realized that the photos uploaded to Getty Images had been published. With media outlets calling for comment, I further grasped the magnitude of what I had witnessed. It was the worst mass murder in modern U.S. history.

I put my head down and cried.

When the brush kicked off on Dec. 4 in Santa Paula, Calif., I skipped ahead—following the direction of the wind—and positioned myself in the path of the flames in Ventura. Chaos ensued; fire was spreading everywhere and burning indiscriminately. Some people evacuated early while others stayed behind until the very last moment before packing up their cars. The electricity was out and visibility was poor due to the smoke.

I parked my car on a street in the darkness and, with the engine still on, I walked up to a cluster of fire moving in behind a Victorian-styled home. The homeowners were calmly packing up and I recall thinking to myself, “Gosh they are in their pajamas. They were probably asleep.” I made a few frames of what I thought was the most surreal reality of living in beautiful California—under threat of hellfire. I continued to stand there, shivering, and watched as the homeowners drove off into the darkness before I could leave the scene.

Within an hour or two after I made that picture and shared it on social media, a man named Kirby Ditto emailed me and said he had not been able to reach his mother in Ventura but saw the picture I had made of her packing up her car. He said he was “extremely happy and relieved to see that she was able to evacuate.”

In times like that, I was happy to reply: “I saw them drive off, so I’m hopeful they made it to a shelter. Good luck.”

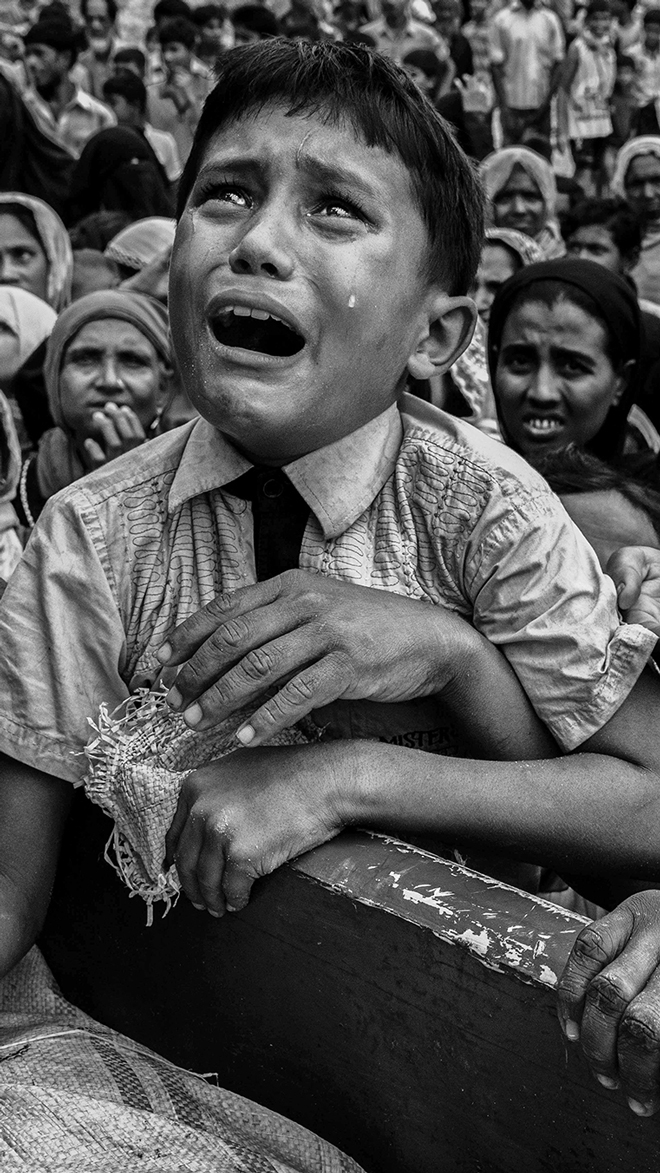

I arrived to Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, in mid-September, a few weeks into the Rohingya crisis. From its early days, I was jarred by the images and stories of the exodus of hundreds of thousands of people with no rights, risking their lives just to survive. I wanted to contribute in some way.

The image of the boy was taken early in that first trip. I was looking for places to photograph food aid because there was such a need for it and so little of it around. I was in an area where there was a crowd of people surrounding a truck. The scene was quite chaotic; people were shouting and reaching because they were obviously distraught and hungry. There was a lot of pushing in the crowd and I wanted to get above it, so I climbed on the truck.

That’s when I saw this small boy. He had just pulled himself up onto the truck and he was weeping. I couldn’t hear much because the scene was so loud, but at one point the boy reached out his hands, begging to the man standing over the food. Then, he wrapped his arms around the man’s legs, clinging to him. I was totally struck by it: he had clawed his way onto the truck in complete desperation. I wish I knew more about him, but he disappeared into the chaos of the moment.

July 2, a Sunday, was the perfect Jersey Shore beach day. Only one problem: A budget fight had forced a shutdown of state-run beaches and parks. Friday and Saturday had been nasty days at the Statehouse in Trenton. Sunday, though, would allow for some cooling off time, and Gov. Chris Christie had already drawn his line in the sand, telling reporters he would go to his private beach on Island Beach State Park even if 9 million other New Jersey residents couldn’t. “Run for governor,” Christie said, “and you can have a residence there.”

I had been planning to fly on Tuesday, July 4, to photograph the state’s crowded beaches. On Sunday, though, I called my regular pilot to see if he was available. When I pulled in at the airport and saw a State Police helicopter—Christie’s ride—I told the pilot, “Let’s go. Right now.”

Minutes later, I saw a single cluster of beachgoers on miles of empty, pristine beach. I was leaning out the window—my right tricep jammed up against the door of the Cessna—to steady myself. We made two quick passes at 40 knots, just under 50 mph. On the second, Christie looked right at me. I fired 86 frames from my Canon EOS-1Dx camera.

The governor threw gas on the fire a few hours later, as I was finishing my edits and captions. “I didn’t get any sun,” Christie said at an afternoon press conference. But the photos were live soon after, just as families across the state were gathering for evening cookouts. The internet erupted. The budget was no longer the story; it was replaced by “beachgate.” By late Monday, the governor signed the budget—in plenty of time for New Jersey residents to reclaim the white sands of Island Beach State Park on the Fourth of July.

It was my birthday, Aug. 1, and my kids were making plans for the evening as we were having breakfast. Soon after, I got a call from a fellow photojournalist about a gun battle raging in south Kashmir and I rushed out. By the time we got there, protests had already spread around to nearby villages. Two top rebels had been killed and a couple of residential houses were destroyed with explosives during the operation.

The media usually covers the funerals of rebels and civilians in these situations, so we hung around and covered the funeral of one the rebels. Then we got news that a civilian had also been killed in one of the villages nearby. I reached the house of Firdous Ahmad Khan, a 30-year-old, who according to the police was killed in the crossfire between rebels and security forces. The villagers alleged he was killed during the clashes with police, not during the gun battle.

His family was quite obviously in shock and devastated with their loss, and I saw the deceased’s pregnant wife and his sisters wailing while other relatives and villagers comforted them. I quickly shot a few frames and left as I didn’t want to intrude on a very private moment of inconsolable grief and loss of a loved one. Their cries were all I could hear on the ride home.

As I entered my house, tired and still shaken, my wife and kids came rushing out to hug me. Before I knew it, I was in the midst of my own birthday party celebrations. I smiled and went through the evening with a smile on my face and anguish in my heart. At the time, I remember how hard I struggled to reconcile the horrific scenes of fighting and killing and grieving with the fact that, there I was a little while later, in the cocoon of my own family—at least outwardly—celebrating my own birthday. It was a birthday I won’t forget.

This was supposed to be my last day on the job at The Daily Progress. Several weeks earlier, I had accepted a new job outside of journalism, but I made sure to schedule that start date for after the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville on Aug. 12.

All morning, fights had broken out as people from different groups continued to arrive and everybody was on edge. Before the rally itself could even begin, the whole area was declared an unlawful assembly while police cleared everybody away. A few hours later, I came across a group of several hundred counterprotesters marching together, chanting and singing. It was the calmest the city had felt all day. I ran ahead of them as they reached 4th Street, and made some pictures of the crowd as they moved toward me.

I crossed the street as I photographed the crowd in front of me. A few seconds after I reached the far sidewalk, I heard a car speed past, coming from behind me. That was the only indication that anything out of the ordinary was happening. The moment the car passed me, I grabbed my camera and followed it with my lens, taking as many photos as possible. It was pure reflex. Years of photojournalism experience had prepared me to react instinctively, and it was more muscle memory than intentional composition that led to those photos.

After the car drove into the crowd of people, it backed up the same road it had just driven down. I followed the car and continued taking photos, and when it reached the nearest cross street, it turned and kept driving. I ran after the car, but by the time I made it to that cross street, the car was out of the area. It wasn’t until that moment that I was able to look at my camera, and realized I might have a photo of the attack. Before then, I wasn’t sure if I had any photos at all. Everything happened so quickly that I could just as easily have ended up with a blurry mess.

I briefly met our other photographer, Andrew Shurtleff, who was nearby and came to cover the aftermath, and then I left to grab my laptop from my car so I could send photos back to the newsroom. I knew this would be a defining moment of the day, but it wasn’t until I was looking at full-sized photos on my computer that I realized the true impact of what had happened.

So far, witnessing the attack hasn’t haunted me the way I expected it to. I still jump whenever I hear the screech of car tires, but fortunately that’s been the extent of the aftermath. I think seeing everything through a camera lens provided some separation. However, the images are burned into my brain, and I don’t think I’ll ever be able to forget them.

While looking for belugas on the eastern shore of Somerset Island, in the Canadian Arctic, our group, an expedition team from SeaLegacy, came to a bay where we found an unoccupied fishing camp. Looking through binoculars, we saw a white form lying on the ground but could not quite tell what it was. We stared for a long time until it lifted its head and we realized it was a polar bear that looked very weak.

We decided to go on land to better assess the situation and quietly situated our cameras behind one of the sheds, as not to disturb him and waited while he slept, some 500 feet away. After a while, he slowly got up and laboriously started walking towards us. It was then that we realized just how terrible his condition was. He looked emaciated, with muscles atrophied to the point he could barely hold himself up as he searched for something to eat. From an old oil drum, he pulled a piece of trash that looked like burnt foam and started chewing on it.

Our team was heartbroken and struggled to process what we were witnessing. The polar bear wandered around a little more, and eventually laid on the ground once again. Shortly after that, he got up and made his way into the water. At first, we thought he might not be able to swim, but he seemed more at ease and agile as he swam away.

As the debate over climate change continues to rage around the world, we wanted to let audiences know what the fate of Arctic wildlife might look like in the absence of decisive action.

I was on assignment for the Associated Press in Mosul, covering the offensive to retake control of Iraq’s second largest city from Islamic State fighters. It was a couple of months into the operation and Iraqi forces had already liberated the eastern side of the city. The more densely populated western side still had many months of brutal and devastating fighting ahead. I remember being shocked by the amount of destruction left behind as the troops advanced into Islamic State-held territory.

One day, as we drove through one of these destroyed neighborhoods, I noticed this surreal scene of a car somehow hanging atop what was left of a house. The street appeared to be abandoned, and after checking that it was safe, I decided to walk into the area and take some pictures. At one point, I climbed on top of the rubble from another house across the street to get a better angle. As I got ready to take a photo, a boy appeared out of nowhere, peacefully riding his bike. He looked at me for a moment, without stopping, probably as surprised to see me as I was to see him.

After this brief encounter I was left wondering what became of him. Although I returned to Mosul several times, I never saw him again. When I look back at this photo and see the horror from which thousands have fled, I also think about those who stayed and somehow kept going.