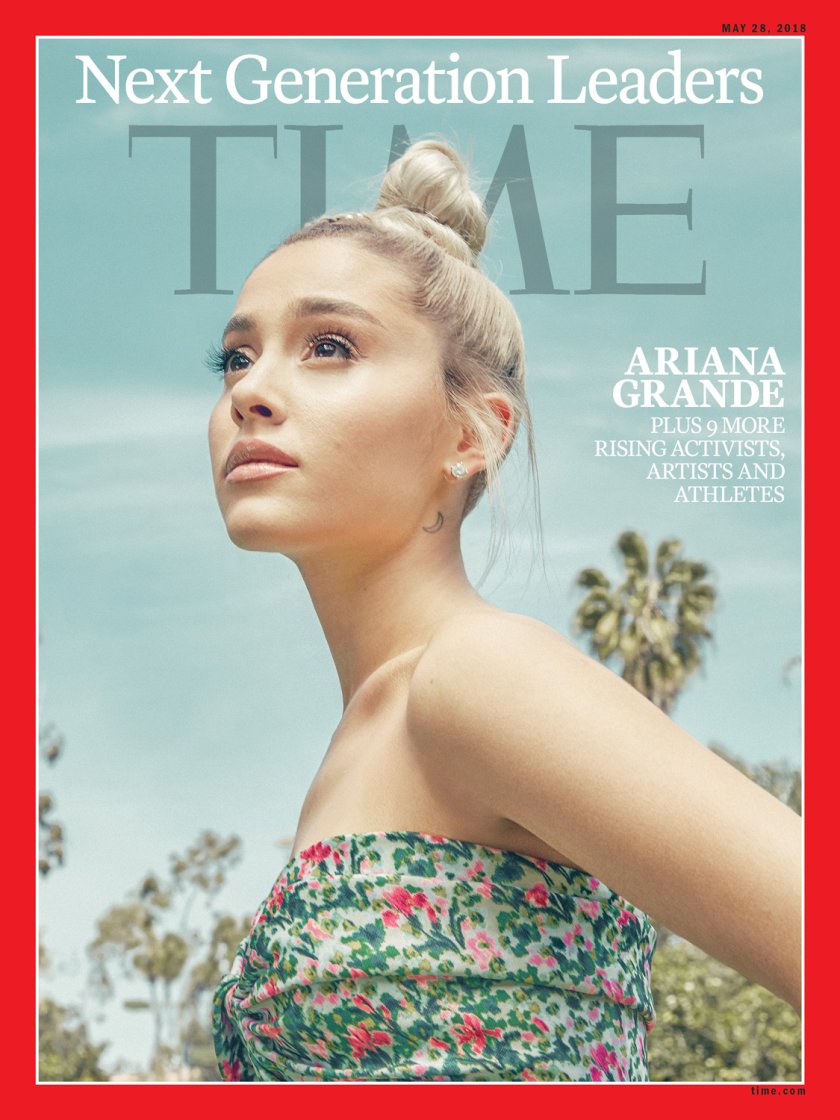

10 young stars who are reshaping music, sports, fashion, politics and more

Since 2014, TIME’s biannual Next Generation Leaders franchise, produced in partnership with Rolex, has featured more than 60 young people who are blazing new trails in politics, entertainment, fashion, science, sports and more. And many have gone on to make a profound impact on the world.

To reach the latest Next Generation Leaders edition, click here.

Ariana Grande Is Ready to Be Happy

The Weeknd Opens Up About Fame, Relationships and ‘Melancholy’

Adwoa Aboah Is Redefining Traditional Beauty Standards

Anthony Boyle: Taking the Stage

Farida Ado: Kano’s Jane Austen

Kerstin Forsberg: Fighting to Save Our Oceans