For now, the U.S. feels the ball is in Moscow’s court

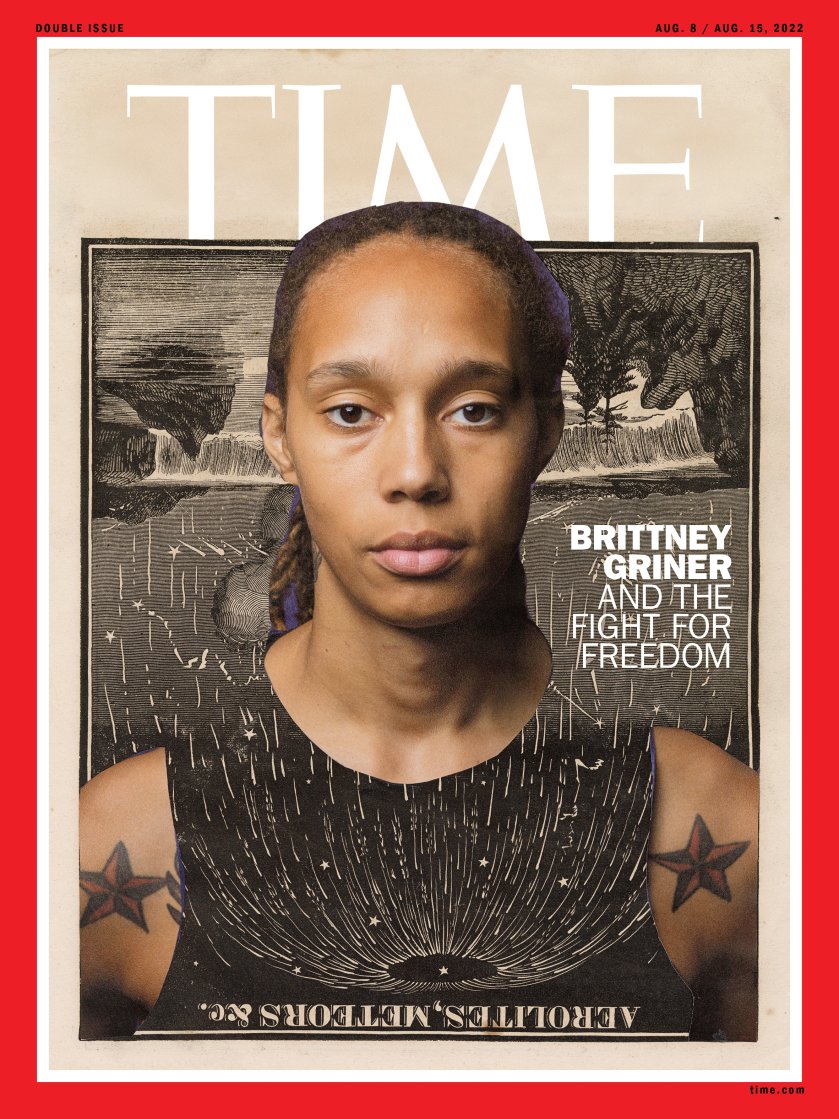

Brittney Griner speaks to the world through pictures these days. In mid-May, nearly three months into her detention in Russia for carrying cannabis oil in her luggage at a Moscow airport, fans of the WNBA superstar saw a stark image of Griner in a courtroom, handcuffed and head bowed, a figure of defeat, her face obscured, braids dangling from a hooded sweatshirt. We saw her eyes in June, at another hearing, but they were popping, frightened, and bewildered. The courtroom cameras stunned her.

As one of the most dominant players in the history of women’s basketball, Griner—affectionately known as BG to friends and fans—has always represented something bigger than just athletic excellence. As an out gay woman who has overcome bullying, hate, and alienation, she has served as inspiration, especially to fellow members of the LGBTQ+ community, for how to live out loud and proud. Now, “wrongly detained” in the euphemistic lingo of international diplomacy, Griner unwittingly has come to stand for even more.

Griner is the most visible detainee among thousands taken by Russia amid its invasion of Ukraine this year, a high-profile prisoner exploited by a regime looking to showcase the limits of American power. Her imprisonment advances President Vladimir Putin’s efforts to humble U.S. President Joe Biden, who has been simultaneously criticized for failing to win Griner’s release and for prioritizing her case over those of other long-detained Americans abroad. At home, Griner’s detention has fueled outrage at the lack of equal rights for LGBTQ+ and Black people, an inequity long exploited by Moscow’s propagandists but nonetheless evident everywhere in American society.

Get a print of the Brittney Griner cover here

President Biden has approved a plan to offer the release of convicted arms dealer Viktor Bout in exchange for the Russians’ release of Griner and Paul Whelan, an American held captive in Russia for more than three years, sources familiar with the matter tell TIME. Moscow “should be interested” in the offer “based on their prior representations,” a senior Administration official says, but as of July 27 had not responded to the offer. That leaves Griner at the mercy of the Russian judicial system, long criticized in the U.S. and Europe as subject to the whims of Moscow’s leaders. Griner’s Russian lawyers have told authorities that U.S. doctors prescribed her medical cannabis. She pleaded guilty, arguing that she accidentally packed the prohibited substance in haste. On July 27, Griner testified that when she was initially interrogated at the airport, much of the communication was left untranslated.

In this high-profile battle between two nuclear powers locked in a historic contest in Ukraine, it’s easy to forget the core tragedy of Griner’s case. Despite her hardships in life, she had thrived. Nike signed her as the company’s first out gay athlete. She found love. She’s in the prime of her life, hitting her stride as a public figure, wife, sibling, and daughter, and teammate, and friend. And now this. “The toughest moment during this ordeal is when I stop to think about how BG is doing,” Griner’s wife Cherelle writes to TIME in an email. “Those moments are overwhelming, and I’m consumed with emotions.”

Though her fate remains uncertain, July delivered moments of hope for Griner. After Griner, who faces a potential 10-year prison sentence, wrote Biden a July 4 letter urging him to bring her home, the President and Vice President spoke to Cherelle, publicly signaling the priority of her case. In her courtroom cage, she held up a photo of the WNBA All-Stars who played a whole half wearing her Phoenix Mercury jersey. There were courtroom testimonials from friends on UMCC Ekaterinburg, the Russian team for which she plays during the U.S. off-season. In one snapshot, she even flashed a grin—between the metal bars. “It helps me sleep better at night,” says Dawn Staley, Griner’s coach on last year’s gold-medal Tokyo Olympic team, “just knowing that she could smile.”

Read more: Spotlight or Silence? A Former FBI Agent on the Best Approach to Help Brittney Griner

Those close to Griner worry that the longer she remains imprisoned, the more likely the psychological trauma she’s spent a lifetime shedding returns. She grew up in Houston, the daughter of local sheriff and Vietnam-veteran father Raymond, and homemaker mother Sandra. As a girl, Griner liked fixing cars with her dad. She wrestled her dog in the mud. Her mom got her Barbie dolls. Griner cut off their hair and painted them green and black.

Griner began to realize she was different. “Everybody always talks about how we should celebrate the things that make each of us special,” Griner writes in her 2014 autobiography, In My Skin. “The problem is, a lot of people are full of crap when it comes to following their own advice.” Kids would poke at her chest, asking if she was a boy. She drew pictures in a notebook in her bedroom: someone was always crying. Griner wept into her stuffed animals. She scribbled down thoughts like Please just make me normal when I wake up.

Griner never played organized basketball before high school. She joined the volleyball team in the fall of her first year at Houston’s Nimitz High. During a game, basketball coach Debbie Jackson spotted the 5-ft. 10-in. freshman and asked her to try out for hoops. “I remember the first day she shot the ball,” says Janell Roy, a high school teammate who would become Griner’s lifelong best friend. “It was terrible. We were like, ‘Yo, you really can’t play!’ ”

Her skills improved as she sprouted nearly a foot in high school. A 2007 YouTube clip, featuring her slamming it home, was an early viral hit. Diana Taurasi, Griner’s future pro teammate with the Phoenix Mercury and overseas, recalls watching the video from Russia, where she was playing at the time. “These were grownup dunks,” says Taurasi. “We were just like, ‘Well, that’s the future of basketball. We might not have a job for very much longer.” Some of her high school stats—like 25 blocks in one game—were cartoonish.

During her senior year, Griner’s father learned his daughter was gay. “You can pack your bags and get the f-ck out!” she says he told her. Griner stayed at the home of her assistant coach for seven weeks. Tension lingered, though her father has grown more accepting. They are now very close.

Griner committed to Baylor, the world’s largest Baptist university. During her junior year of high school, Griner told Baylor coach Kim Mulkey she was gay. “As long as you come here and do what you need to do and hoop, I don’t care,” Mulkey said, according to Griner’s book. But Mulkey, Griner says, acted different once she got to campus. Griner was unaware that Baylor prohibited “advocacy groups which promote understandings of sexuality that are contrary to biblical teaching.” After Griner went out with her girlfriend on Valentine’s Day, Mulkey chastised her for failing to “keep your business behind closed doors.” A spokesperson for LSU, where Mulkey now coaches, did not return an interview request from TIME; Baylor chartered its first ever LGBTQ+ group this April.

Living in the shadows stressed Griner out. On occasion, her anger would appear on the court. As a freshman, Griner received a two-game suspension for punching a Texas Tech player, breaking her nose. Mulkey ordered Griner into therapy after that incident; she found talking to someone helpful, and continued with therapy through adulthood.

In 2013, the Mercury selected Griner as the top overall pick. On the court, Griner at first deferred to Taurasi, an all-time great. “She’s the most unselfish superstar player I’ve ever been around,” says Taurasi. “I would have to get into her to demand the ball.” The Mercury won the WNBA title in 2014, Griner’s second year in the league.

Things got rocky in her personal life. Griner married former WNBA player Glory Johnson in 2015, despite their both being arrested after an argument turned physical just weeks prior. Griner filed for an annulment after 28 days. “The biggest thing during that is she did not want to feel like a failure,” says Roy: “Where do I go from here—where people don’t think I’m this monster?”

Griner’s physicality on the court belies her more personable nature. When Cherelle first met Griner, at Mooyah Burgers on the Baylor campus, she was struck by how she seemed to know every employee. “She often will go eat her lunch in the employee lounge at the arena in Phoenix with the security, because she says, ‘I want to know all my co-workers,’” says Cherelle.

When partnering with a local nonprofit, the Phoenix Rescue Mission, to drive around the city delivering shoes to those in need, she once opened the doors of a van, grabbed boxes of shoes, and took off toward a group of homeless people. “It wasn’t, ‘You guys go first,’” says Danny Dahm, street-outreach supervisor at the mission. “She was like, ‘Let’s do this.’ She wasn’t afraid to touch people.”

Griner also has a goofy side. “She’s one of those who will throw a ball at you in the middle of the aisle at Walmart, and take off running,” says Roy. Griner appreciates the “big person in tiny contraption” sight gag. She once skittered around the sales floor of the Mercury offices on a motorized tricycle, waving to team employees. Mercury players spend a day working at a grocery outlet that sponsors the team. “She’ll end up in a shopping cart every year, like a 5-year-old would but with her 6-ft. 9-in. legs hanging out,” says Mercury president Vince Kozar. “And every year she ends up on a microphone asking for a price check on green beans, or something else that she doesn’t actually need.”

The slights that once stung now roll right off her. “She doesn’t let that sh-t faze her,” says Olympic teammate Sue Bird. “There are times when she would get mistaken for a guy. She would walk into a woman’s bathroom and someone would stop her and be, ‘Oh, no, this is not your bathroom.’ I’ve heard people call her sir at an airport. ‘Excuse me, sir, can you come this way?’ She’s just like, ‘Whatever.’ She almost has a vibe about her. ‘No one’s going to ruin my day.’”

“She lives in peace,” says Staley. “She’s been through things in her life, trials and tribulations. Yet no one’s going to shake her equilibrium. That’s who you love.”

Griner has spent her WNBA off-seasons since 2014 at the gateway to -Siberia, playing for UMMC Ekaterinburg, a club that pays Griner the more than $1 million salary unavailable to her in the U.S., where she’ll make $228,000 this year. “BG loved playing in Russia,” says Cherelle. “They value women’s basketball.” Griner took great pride in winning four -Euro-league championships. “She called Yekaterinburg her second home, and this is not an empty phrase,” Maxim Rybakov, UMMC Ekaterinburg’s general manager, testified at a July 14 court hearing. “Even after the warning from the U.S. intelligence agencies, Brittney was determined to continue playing for the team.”

He called Griner the team’s “moral leader.” Her Russian teammate Evgenia Belyakova testified it was “difficult to overestimate” Griner’s contribution to Russian basketball. “She is currently,” said Belyakova, “the most beloved player in Russia.”

Putin doesn’t seem to care. Since the days of the Soviet Union, Russia has stoked American racial divisions for its own gain. In the 1960s, Soviet newspapers covered the civil rights movement, pointing out the hypocrisy of a democratic system that preached freedom to the world but treated its own Black citizens so poorly. A 2019 Senate Intelligence Committee report found that Russian operatives created social media accounts and advertisements discouraging Black Americans from voting, in order to boost the candidacy of Donald Trump.

Griner’s arrest has already flared tensions in America. “If this was LeBron James, Tom Brady—you can go into any professional men’s sport—if this was a man, he would have been home by now,” Natasha Cloud of the Washington Mystics tells TIME. “It would have been a priority. Unfortunately, BG has fallen into that realm being a woman, being a gay woman, being a gay Black woman.” When James himself wondered aloud, on his talk show The Shop, if Griner would even want to return to America—“How can she feel like America has her back?” he said—conservatives pummeled him as anti-American. He tweeted a clarification that he “wasn’t knocking our beautiful country.”

Putin delights in such rancor. “He’s creating mischief and mayhem,” says Fiona Hill, the former senior director for European and Russian affairs on the National Security Council under President Trump. With Biden’s approval ratings sinking to new lows, Putin may be loath to release Griner and hand his counterpart any semblance of a PR win. “What I and others fear,” says Hill, “is that the more she can become a wedge issue, the more Biden and the White House gets castigated, the more valuable she becomes for them to keep.”

After an initial strategy of quiet wrangling to free Griner, the U.S. government has raised the volume on her case. Russian officials have publicly stated that they don’t appreciate the pressure. “The Biden Administration needs to rein it in,” says Jason Poblete, an attorney who has represented U.S. citizens held hostage abroad. “They’ve made a big mistake escalating it the way that they did.”

For now, the U.S. feels the ball is in Moscow’s court. In late April, the countries swapped Konstantin Yaroshenko, a convicted Russian drug trafficker jailed in Connecticut, for Trevor Reed, a former Marine accused of assaulting a Russian police officer; Reed had spent 985 days in Russian detention. Russia has previously called for the release of Bout, who was convicted of conspiring to sell weapons to terrorists in 2011 and sentenced to 25 years in prison. The U.S. judge in Bout’s case, Shira A. Scheindlin, told TIME that if she weren’t restricted by minimum sentencing guidelines, she would have given Bout some 10 years, which is now about the length of time he’s been in prison.

Some Biden Administration officials fundamentally oppose prisoner swaps, fearing they may further incentivize hostage-taking abroad. And letting go of Bout has been a tough sell for those focused on human rights, international crime, and other matters. But “the President has been clear about the need to bring [Griner and Whelan] home,” says the senior Administration official. Biden’s approval of an exchange of Bout for Griner and Whelan was first reported by CNN.

Bout’s inclusion in any trade proposal signals Griner’s importance to Biden; the pro-swap advocates, for now, are winning out. Mickey Bergman, vice president and executive director of the Richardson Center for Global Engagement, traveled to Moscow with former U.N. ambassador Bill Richardson in February to meet Russian officials about Reed’s and Whelan’s cases. He cites a 2018 Rand Corp. study concluding “there is little historical evidence to support the contention that a no-concessions policy reduces kidnappings.”

Arguments to the contrary are “intellectually lazy and morally bankrupt,” Bergman says, “because the government efforts to disincentivize and deter the taking of Americans cannot be done on the backs of those already imprisoned.”

Griner is tired and stressed in detention. But seeing photos of the WNBA All-Star tribute put her in a good mood. The support from the basketball community and her family “is very important to BG and helps to remain optimistic,” says her Russian lawyer, Maria Blagovolina.

Besides the Bible, she’s reading Demons, by Dostoevsky, while in jail; she’s also finished works by Kafka and James Patterson, and the memoirs of rockers Keith Richards and Gregg Allman. Outside communication is infrequent and monitored, but many players and coaches have penned notes to her. Staley encouraged her to summon the dominant BG. Seattle Storm star Breanna Stewart informed Griner her baby daughter cries whenever she goes near a Roomba. “You’re trying to give her hope and strength and things like that, but also want her to think about some other silly things,” says Stewart.

Staley says Griner wrote about how she was the biggest person in jail. “You can tell she’s trying to find the joy of just waking up every day,” says Taurasi. “The first letter she wrote back, she said she tried to go vegan the first week, but that didn’t work. She went back to eating meat. Which is kind of funny. Only BG would try to go vegan in a Russian prison.”

While her loved ones fear for her mental health, they also believe that all the strife she’s faced—being taunted because of her appearance, rejected because of her sexuality, assumed to be something she’s not—have prepared her to meet this awful moment. “People don’t even know how much she has already pushed through,” says Roy. “For me to know her past journey, and some of the things that she’s dealt with, I can tell you that my sister is not going to come back weak. That’s for sure. She’s only going to come back stronger.” —With reporting by Brian Bennett, Vera Bergengruen, and Massimo Calabresi/Washington; Solcyre Burga, Mariah Espada, and Simmone Shah/New York; and Mariia Vynogradova/London