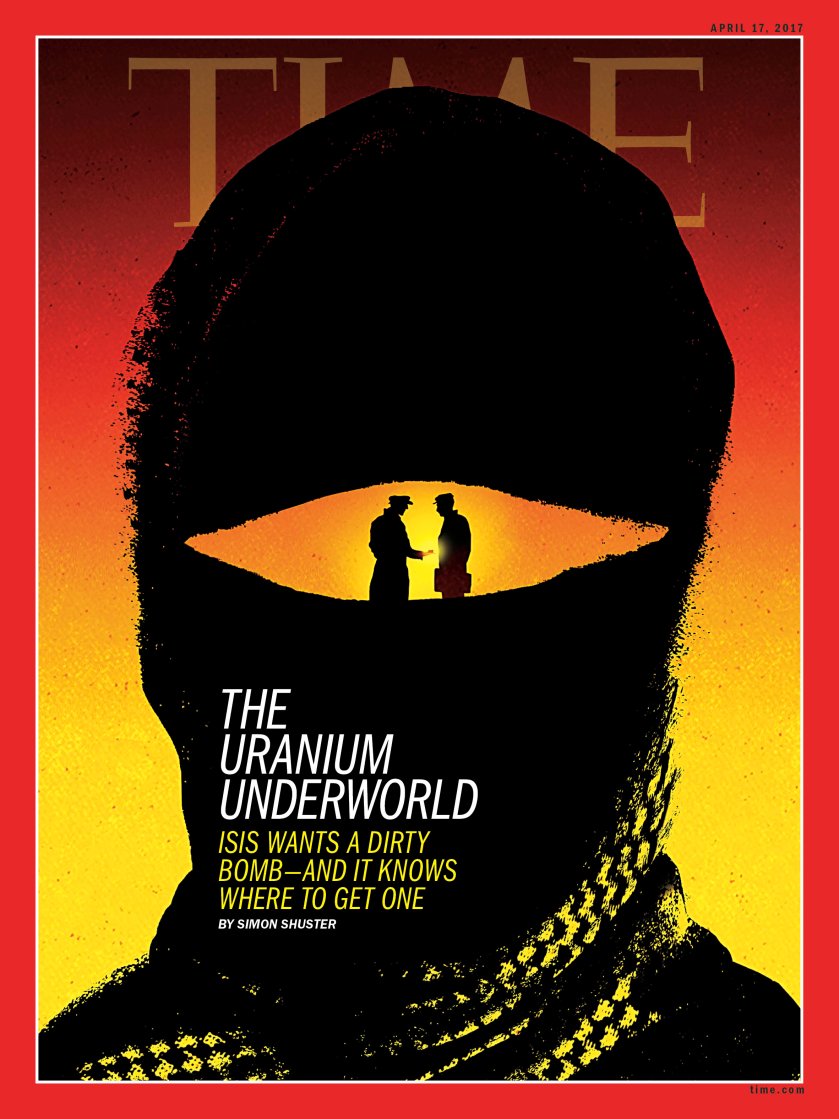

A nuclear threat lurks in the lawless hinterlands of the former Soviet republics

One night last spring, Amiran Chaduneli, a flea-market trader in the ex-Soviet Republic of Georgia, met with two strangers on a bridge at the edge of Kobuleti, a small town on the country’s Black Sea coast.

Over the phone, the men had introduced themselves as foreigners—one Turkish, the other Russian—and they were looking for an item so rare on the black market that it tends to be worth more, ounce for ounce, than gold. Chaduneli knew where to get it. He didn’t know that his clients were undercover cops.

From the bridge, he took them to inspect the merchandise at a nearby apartment where his acquaintance had been storing it: a lead box about the size of a smartphone, containing a few pounds of radioactive uranium, including small amounts of the weapons-grade material known as uranium-235. The stash wasn’t nearly enough to make a nuclear weapon. But if packed together with high explosives, these metallic lumps could produce what’s known as a dirty bomb—one that could poison the area around the blast zone with toxic levels of radiation.

In the popular culture, the dealers who traffic in such cargo are usually cast as lords of war with tailored suits and access to submarines. The reality is much less cinematic. According to police records reviewed by TIME in Tbilisi, the Georgian capital, Chaduneli’s associates in the attempted uranium sale last spring included construction workers and scrap-metal traders. Looking at the sunken cheeks and lazy left eye in his mug shot, it seems improbable that lousy capers like this one could rise to the level of a national-security threat. But the ease of acquiring ingredients for a dirty bomb is precisely what makes them so worrying.

As the number of nuclear-armed countries has grown from at least five to as many as nine since the 1970s, the danger of World War III has been joined by a host of secondary nuclear threats. The possibility that a warhead, or the material to build one, could fall into the hands of a rogue state or terrorist helped drive President Barack Obama’s deal to temporarily halt Iran’s alleged weapons program. North Korea, which is now believed to have more than a dozen warheads and has been busily testing intercontinental missiles to carry them, has also been the world’s most active seller of nuclear know-how. Pakistan is developing battlefield tactical nuclear weapons, which are smaller and more portable than strategic ones, even as its domestic extremist threat grows.

The danger from dirty bombs is spreading even faster. For starters, they pose none of the technical challenges of splitting an atom. Chaduneli’s type of uranium was particularly hard to come by, but many hospitals and other industries use highly radioactive materials for medical imaging and other purposes. If these toxic substances are packed around conventional explosives, a device no bigger than a suitcase could contaminate several city blocks—and potentially much more if the wind helps the fallout to spread. The force of the initial blast would be only as deadly as that of a regular bomb, but those nearby could be stricken with radiation poisoning if they rushed to help the injured or breathed in tainted dust. Entire neighborhoods, airports or subway stations might need to be sealed off for months after such an attack.

The lasting effects of a dirty bomb make this weapon especially attractive to terrorists. Fear of contamination would drive away tourists and customers, and cleanup would be costly: the economic impact could be worse than that of the attacks of 9/11, according to a study conducted in 2004 by the National Defense University. “It would change our world,” President Obama said of a potential dirty bomb in April 2016. “We cannot be complacent.”

Obama’s successor is certainly alive to the nuclear threat. In a Republican primary debate in December 2015, Donald Trump said the risk of “some maniac” getting a nuclear weapon is “the single biggest problem” the country faces. But he suggested that the world would be safer if more countries acquired nukes. His Administration has yet to set out a policy for countering the danger of a dirty bomb; the position Trump takes could be crucial. By training and equipping foreign governments to stop nuclear traffickers, the U.S. has played a central role in fragile or unstable areas of the world where highly dangerous materials can fall into the wrong hands. The goal, according to Simon Limage, who led the State Department’s nonproliferation efforts during the last five years of the Obama Administration, is “to push the threat away from U.S. shores.”

Georgia is one of the best examples of how these efforts have worked on the ground. Over the past 12 years, the U.S. government has provided more than $50 million in aid to help the former Soviet republic, a nation of only 3.7 million people, in combatting the trade in nuclear materials. Though it possesses no nuclear fuel of its own, Georgia sits in the middle of what atomic-energy experts sometimes refer to as the “nuclear highway”—a smuggling route that runs from Russia down through the Caucasus Mountains to Iran, Turkey and, from there, to the territory that ISIS still controls in Syria and Iraq.

All along that route, the U.S. has helped install nuclear detectors at borders, trained police units to intercept traffickers and provided intelligence and equipment to local regulators of nuclear material. “The Americans brought all the technology,” says Vasil Gedevanishvili, director of Georgia’s Agency of Nuclear and Radiation Safety. “They secured every border around Georgia.”

The payoff was clear in 2016, when Georgian police busted three separate groups of smugglers for attempting to traffic in nuclear materials—a spike in arrests the region hadn’t seen in at least a decade. They foiled an attempt in January to smuggle cesium-137—a nasty form of nuclear waste that could be used in a dirty bomb—across the border into Turkey. Three months later, on April 17, Georgian police caught a group of traffickers trying to sell a consignment of uranium for $200 million.

At the end of that month, Chaduneli and four of his associates were arrested in Kobuleti by a team devoted to countering nuclear trafficking that has received training, equipment and intelligence from various arms of the U.S. government. “So in some sense this was a success story,” says Limage, who met the team during a visit to Georgia in December, less than two months before he resigned from his post as Deputy Assistant Secretary of State. “But none of the gains we’ve made with these partnerships are permanent. They’re all reversible.”

And they’re becoming even more essential to international security. Over roughly the past three years, as the U.S.-led coalition has advanced against ISIS in Syria and Iraq, the terrorist group has been shifting tactics. Rather than urging its followers to come join the fight in Syria, ISIS recruiters now call for attacks against the West using whatever weapons are available. The continued erosion of the group’s territory may not make it any less dangerous. “It may make them more desperate,” says Andrew Bieniawski, vice president of the Nuclear Threat Initiative, a U.S. nonprofit that works to reduce the risk of nuclear weapons and materials. “And they may try to raise the stakes.”

There have already been plenty of signs that ISIS would like to go nuclear. After the series of ISIS-linked bombings in Brussels killed at least 32 people in March 2016, Belgian authorities revealed that a suspected member of a terrorist cell had surveillance footage of a Belgian nuclear official with access to radioactive materials. The country’s nuclear-safety agency then said there were “concrete indications” that the cell intended “to do something involving one of our four nuclear sites.” About a year earlier, in May 2015, ISIS suggested in an issue of its propaganda magazine that it was wealthy enough to purchase a nuclear device on the black market—and to “pull off something truly epic.”

Though the group is unlikely to possess the technical skill to build an actual nuclear weapon, there are indications it could already possess nuclear materials. After the group’s fighters took control of the Iraqi city of Mosul in 2014, they seized about 40 kg of uranium compounds that were stored at a university, according to a letter an Iraqi diplomat sent to the U.N. in July of that year. But the U.N.’s nuclear agency said the material was likely “low grade” and not potentially harmful. “In a sense we’ve been lucky so far,” says Sharon Squassoni, who heads the program to stop nuclear proliferation at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. “I honestly think it is only a matter of time before we see one of these dirty-bomb attacks.”

Obtaining ingredients for such a weapon is not, it turns out, the hard part. According to Chaduneli’s lawyer, Tamila Kutateladze, his associates found the box of uranium in one of the scrapyards where he would find old bric-a-brac to sell. His co-defendant in the case, Mikheil Jincharadze, told police that “unknown persons” had delivered the box inside a sack of scrap iron, according to interrogation records and other court documents obtained by TIME in Georgia.

That version of the story did not convince investigators, and even Chaduneli’s lawyer wondered how such a thing could turn up in a pile of trash. “A mere mortal cannot just get his hands on this stuff,” Kutateladze told TIME in her office in Tbilisi. “You have to have a source.”

But the Georgian authorities have so far been unable to determine that source with any certainty. Similar investigations in the past, most recently in 2010 and 2011, have traced the nuclear material back to reactors in Russia. Among the most famous cases involved a small-time Russian smuggler named Oleg Khintsagov, who tried to sell a sample of highly enriched uranium in 2006 to a Georgian police officer posing as a wealthy Turkish trafficker. “He said he could get much larger quantities from his sources in Siberia,” recalls Shota Utiashvili, who oversaw that case as Georgia’s Deputy Interior Minister at the time. “We think it’s from an old stockpile of this stuff that’s been laying around and periodically looking for a buyer.”

During the chaos that followed the Soviet collapse in the early 1990s, radioactive material was frequently stolen from poorly guarded reactors and nuclear facilities in Russia and its former satellite states. Police intercepted shipments of it transiting through cities as faraway as Munich and Prague in those years, and nuclear experts believe that large batches of Soviet nuclear fuel are still unaccounted for and most likely accessible for well-connected traders on the black market.

The potential source that most concerns investigators in Georgia is the region of Abkhazia, a Russian protectorate that broke away from Georgian control in the early 1990s. It is one of several unrecognized pseudo states—often referred to as frozen conflict zones—that Russia has helped maintain in the former Soviet space. With no internationally acknowledged borders, these regions often function as way stations for smugglers, allowing everything from guns and cigarettes to contraband caviar to be trafficked under the radar of international law. “These spaces are ungoverned,” says Squassoni of CSIS. “So what we risk when we look at these conflict-torn regions is that people will try to make a living any way they can, and they may not have any scruples about what they’re smuggling across these borders.”

On the border between Moldova and Ukraine is the pro-Russian enclave of Trans-Dniestr, where Moscow has stationed about a thousand troops since the region’s violent split from Moldova in the early 1990s. This sliver of land along the Dniestr River was a base for one of the world’s most notorious nuclear smugglers, Alexandr Agheenco, a dual Russian-Ukrainian citizen nicknamed the Colonel, who is wanted by U.S. and Moldovan authorities for attempting to sell weapons-grade uranium to Islamist terrorist groups in 2011. One of his middlemen was caught that year in a Moldovan sting operation; police reportedly found the blueprints for a dirty bomb in his home. But the Colonel remains at large.

More recently, Russia has carved a fresh pair of conflict zones out of eastern Ukraine, where separatist rebels used weapons and fighters from Russia in 2014 to seize territory around the cities of Luhansk and Donetsk. According to research compiled by CSIS, the war has destroyed 29 of the radiation detectors that would normally monitor the movement of nuclear material along the border between Russia and Ukraine.

But Abkhazia is the only one of these conflict zones that has ever possessed its own nuclear facilities. Physicists recruited from Germany after World War II set up the first Soviet centrifuges at the Sukhumi Institute of Physics and Technology, which remained a key pillar in the Soviet nuclear program through the Cold War. After the fall of Soviet Union, the newly independent Georgian government fought separatists who wanted to keep Abkhazia within Moscow’s orbit.

When the civil war reached Sukhumi in 1992, its scientists set up patrols to protect their stores of radioactive material from looters and paramilitaries. The war ended the following year with Abkhazia’s de facto secession from the rest of Georgia, and the fate of its nuclear stockpiles has been something of a mystery for international observers ever since.

Officials in Russia say there is no longer any nuclear material in Abkhazia. But Georgia disputes this. Gedevanishvili, the head of the country’s nuclear-safety agency, says the Sukhumi Institute still conducts experiments using radioactive sources. “We don’t know what security measures they take. We know nothing about their work.”

Russia has its own reasons to worry about dirty bombs. The explosion that killed at least 14 people and wounded dozens of others in the St. Petersburg metro on April 3 was just the latest of dozens of terrorist attacks since the early 1990s. Over that time, Moscow has worked to secure nuclear stockpiles throughout the former Soviet Union, often with help and funding from the U.S. But as relations with Washington have eroded, Moscow has cut off cooperation, insisting it no longer needs American assistance.

Whether he wants to or not, President Trump will play a key role in determining the danger from dirty bombs in coming years. Since his election, Trump has denounced the work of the U.N. as a “waste of time and money,” even though U.N. organizations like the International Atomic Energy Agency are responsible for monitoring nuclear stockpiles and advising countries on keeping them safe. Trump’s pick to lead the Department of Energy, former Texas governor Rick Perry, previously called for its dissolution, but defended its mission during nomination hearings; the department oversees the U.S. nuclear arsenal and safety at nuclear sites.

Trump’s new budget proposal, which the White House published on March 16 under the title “America First,” would slash programs that contribute to U.S. security in ways subtler than guns and walls. It would cut foreign aid, diplomacy and development programs—all of which have helped the U.S. forge a global network of alliances against nuclear trafficking. “This isn’t rocket science,” says Limage, the former State Department official. “A lot of the nonproliferation progress that has been made around the world has been through patient, careful diplomacy.” Countries that would otherwise not have the means or the motivation to target smugglers of nuclear material have received regular encouragement, training and aid from the U.S. in these efforts.

The Trump Administration takes the threat “very seriously,” Tom Bossert, President Trump’s Homeland Security Advisor, tells TIME. “The President’s budget blueprint specifically calls out U.S. programs dedicated to reducing the dangers of WMD terrorism or nuclear proliferation,” he says. “We continue to work domestically and with a broad set of international partners and international organizations to better secure any materials that might contribute to WMD terrorism and to mitigate the effects of an attack, should one occur. The prospect of WMD terrorism is one of the many reasons that we must remain vigilant in our counterterrorism efforts across the globe.”

In Georgia, there are obvious risks to letting partnerships lapse. From the bridge where Chaduneli went to meet his buyers, it would take just a couple hours for a dirty bomb’s ingredients to reach Turkey by car or boat, and only days more to reach Syria or Iraq. His family home stands within view of the border with Azerbaijan, a notoriously corrupt dictatorship with links to Iran. Local kids often ride their bikes next to the border crossing, a barbed-wire fence guarded by a few lethargic soldiers.

They are a thin line of defense in an era when nuclear threats emerge not only from military and rogue regimes, but from the hard economic reality of some of the world’s most forgotten places. An honest job in this region brings in a few hundred dollars per month. So the lure of trafficking across these borders is constant, says Chaduneli’s mother Tamila.

The undercover agents who arrested him offered to pay $3 million for that box of uranium. At the end of their trial in December, all of the suspects in Chaduneli’s case took a plea deal in exchange for lighter sentences; Chaduneli got three years in prison. In his one-story home, which has an outdoor kitchen with a wood-burning stove and gets intermittent electricity, his mother says she has no idea how his friends got their hands on a batch of nuclear material—or why her son joined a plot to sell it. “The money,” she says, “might have clouded his eyes.”

—With reporting by ZEKE J. MILLER/WASHINGTON