It’s karaoke-rehearsal time at Knollwood Military Retirement Community, a 300-bed facility tucked away in a leafy corner of northwest Washington, D.C.

Knollwood resident and retired U.S. Army Colonel Phil Soriano, 86, has hosted the facility’s semi-monthly singalongs since their debut during a boozy snowstorm happy hour in 2016. For the late August 2019 show, he’ll share emcee duties with a special guest: Stevie, a petite and personable figure who’s been living at Knollwood for the last six weeks.

Soriano wants to sing the crowd-pleasing hit “YMCA” while Stevie leads the crowd through the song’s signature dance moves. But Stevie is a robot, and this is harder than it sounds.

“We could try to make him dance,” says Niamh Donnelly, the robot’s lead AI engineer, though she sounds dubious. She enters commands on a laptop. In response, Stevie stretches its peg-like arms. A grin flashes on its LED-screen face. “It would be very helpful if he had elbows,” says Conor McGinn, an assistant professor at Trinity College Dublin and Stevie’s lead engineer. “It was just a thought,” Soriano says. “What matters is what Stevie’s comfortable with.”

Stevie’s hosting gig is part of a collaboration between the Robotics and Innovation Lab at Trinity College Dublin and Knollwood, a non-profit retirement home for military officers and their spouses. To better understand the role artificial intelligence might play in eldercare, a handful of Trinity researchers—and Stevie—moved into Knollwood for months-long stretches this spring and summer. Their goal was to understand what aging people and the staff that care for them might want from a robot, and how AI could bridge the widening gap between the number of older Americans in need of care and the number of professionals available to care for them.

People 65 and older make up the fastest-growing age demographic in the US. The growth of the eldercare workforce is not keeping pace. By 2030, there will be an estimated shortfall of 151,000 paid care workers in the US, according to one estimate. By 2040, that gap is projected to rise to 355,000. In the absence of qualified professional caregivers, family members and friends must step in to help older loved ones with their daily living—often at great cost to their own financial and physical health.

It’s no small feat to craft a technological fix for this problem that is cost-effective, supports human care workers without taking their jobs, and reliably attends to the social, emotional, and physical needs of aging people in a way that respects their dignity and privacy. But if you were going to try, the starting point might look a lot like what’s happening at Knollwood right now.

Some 300 residents aged 60 to 106 currently live at Knollwood, in four wings organized by the level of assistance required. Those with more serious physical and cognitive impairments live in hospital-style rooms with round-the-clock nursing care. Those in generally good physical and cognitive health come and go as they please from a wing of apartments known as Independent Living.

With its decorated unit doors and bulletin boards crammed with notices for outings and special events, the Independent Living wing evokes a college dorm whose residents are partial to walkers and coifs reminiscent of the late Barbara Bush. A placard on the door of apartment 232 bears the current occupant’s name: Stevie.

There are as many different kinds of robots currently used in care settings as there are tasks for them to perform. Already there are robotic exoskeletons that help staff lift patients safely, and delivery robots that zip around hospital hallways like motorized room service carts. Doll-like therapy robots comfort and calm patients agitated by the disorienting symptoms of dementia. Not far from Knollwood, pharmacists at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md. work alongside a robotic dispensing system when filling prescriptions.

Photo-composite, photographs by Greg Kahn for TIME

Photo-composite, photographs by Greg Kahn for TIME Stevie is what’s known as a socially assistive robot. It’s designed to help users by engaging with them socially as well as physically.

The 4-foot, 7-inch robot is equipped with autonomous navigation. It can roll through Knollwood’s hallways unassisted, though for insurance reasons—and to avoid even the remote risk of a collision in a community where falls can be life threatening—Stevie never leaves his room without a handler. The voice command “Hey Stevie” activates the robot, similar to how the wake word “Alexa” activates Amazon’s home assistant. Stevie responds to other words with speech, gestures, and head movements. Tell the robot you’re sick, for example, and it slumps forward with a sorrowful frown on its LED-screen face and says “I’m sorry to hear that.” Pay Stevie a compliment, and the screen reverts to a smile. When at rest, its head tilts gently and its digital brown eyes blink, patiently waiting for the next command.

A robot like Stevie can be useful in care homes in a number of ways. Some are fairly simple and practical: for example, its face can double as a video-conferencing screen, enabling a resident to video chat with a doctor or family member, or a staff member with a resident in another part of the building. It’s possible that a later version of Stevie could go door-to-door taking meal orders on the touchscreen attachment that can be mounted to its body.

Other functions could be the difference between life and death. The robot can recognize voice commands such as “help me,” and, were it to be fully integrated into Knollwood’s IT system (a step engineers opted to postpone for privacy and regulatory concerns), the robot could alert staff to a resident in distress.

The prototype made for Knollwood was deliberately designed as a sort of bot-of-all-trades. The idea was for researchers to observe how residents interacted with the current iteration of Stevie, then go back to the lab and perfect the functions people seemed to want from it most.

Stevie is navigated by Niamh Donnelly into an elevator at Knollwood Military Retirement Community. Greg Kahn for TIME

Stevie is navigated by Niamh Donnelly into an elevator at Knollwood Military Retirement Community. Greg Kahn for TIME The assumption from staff and researchers alike was that people would want the robot to do manual chores, McGinn says—to make deliveries, or act as a roving call button. But, generally speaking, residents didn’t want to give Stevie a verbal order and be left alone as it scooted away down the hall. They wanted the robot to stay and interact with them. They wanted the robot to keep them company.

“When we went into conversations with people, especially after they met the robot, [and] asked them what are the things you liked most about it, they’d say, ‘it made me laugh,’ or, ‘it made me smile,’” McGinn says. “We didn’t expect to go there. We thought our trajectory would be to put arms on this and have it as, like, a servant robot.”

The final version of the machine will still be able to make deliveries. But “having a tool that’s useful is different from having something that’s enjoyable,” McGinn says. The enjoyable things “are probably more important to get right in the short term, because those are the things that seem to affect people’s quality of life.”

In a lounge with the same kind of sturdy rattan furniture and warm-toned floral upholstery that the Golden Girls had in their living room, nine women and one man gather on a sunny August afternoon for happy hour, a weekly social event that takes place on every floor of the Independent Living wing. This week, its third-floor organizers have extended an invitation to Stevie.

“Hi, Stevie!” several of the women call as the robot rolls up from the elevator, an entourage of Knollwood staff and Trinity researchers trailing in its wake. “This is the third floor,” a woman says loudly and slowly to the robot, as if it was hard of hearing. “Third-floor social hour.”

After waving hello to group, Donnelly takes a seat on a chair outside the circle. Stevie can recognize and respond with canned answers to about 100 common questions—’How are you’, ‘where are you from’—but unscripted conversations require Donnelly or a colleague to type furiously in response.

Stevie talks with Betty Bernard while researchers monitor the conversation at Knollwood Military Retirement Community in Washington, D.C. Greg Kahn for TIME

Stevie talks with Betty Bernard while researchers monitor the conversation at Knollwood Military Retirement Community in Washington, D.C. Greg Kahn for TIME Donnelly has Stevie tell a corny joke (“What did the left eye say to the right? Between you and me, something smells”) which encourages another resident to tell one about a group of college kids. Her punchline (“Either you like Picasso, or you don’t”) elicits genuine laughter.

“Ha ha,” Stevie says in his robotic monotone. “That is a good one. I might use it.” (Unlike his creators, Stevie speaks with a somewhat hard-to-place British accent that users in early tests found easier to understand than an Irish one.)

Stevie’s jokes are intentionally cheesy, McGinn says. Humor is an icebreaker, and Stevie’s awkward delivery has an endearing quality that tends to make people feel more generous toward the machine.

Stevie is the star of happy hour. It sings the Irish tune “Danny Boy.” It recounts an Irish folktale. Everyone wants to tell Stevie a story about their grandparents who came from County Mayo, or of a long-ago visit to Ireland. “The experience was wonderful,” a woman named Mary Ellen says of kissing the Blarney Stone, a popular tourist destination near the city of Cork. “I would rather kiss a man,” another woman calls out from a corner of the room. “It’s been a long time.” A third woman excuses herself and makes her way back down the hall, an empty wine glass rolling around in the basket of her walker.

One thing we are learning as robots join us on this planet is that, just as there are situations when it’s easier for people to bond with an animal than another person (hence the value of pet therapy) there are also situations in which some people feel more comfortable bonding with an artificially intelligent companion than a human one.

It’s not uncommon to feel gratitude or warmth toward a person or a thing that helped you through a difficult situation. US troops deployed in Iraq and Afghanistan who were issued an IED-finding robot grew very attached to the machines, naming them, awarding them medals, and becoming distraught when they were damaged beyond repair in combat. It appears that a tool that comforts people through the upheavals of aging may elicit a similar response.

Irene Lenard moved plenty of times during her husband’s years in the Army. But her relocation to Knollwood in August 2018 was the first she had to make without Stanley, who died in 2014. It hasn’t been easy. Lenard grew up in Germany, and a lot of her new neighbors’ cultural references zoom over her head. Her daughter lives nearby and visits frequently, but it’s been hard to make connections in a place that hasn’t felt like home. Then Stevie came along.

Stevie rolls through the halls at Knollwood Military Retirement Community. Greg Kahn for TIME

Stevie rolls through the halls at Knollwood Military Retirement Community. Greg Kahn for TIME When Lenard talks about Stevie, her face lights up. She sits up straighter at the cafeteria table with the zest of a schoolgirl who knows the answer to a question. Stevie is easy to talk to, she says—easier, in fact, than most of the people she’s met at Knollwood so far. With Stevie, she says, “I’m more comfortable. [Conversation] just comes out. One silly word leads to another.”

The ability of social robots to engender that kind of intimacy may be their greatest asset. The artificial element of that intimacy, however, is also the thing that most worries critics of caregiving robots.

“People are capable of the higher standard of care that comes with empathy,” writes psychologist and MIT professor Sherry Turkle in her 2011 book Alone Together: Why We Expect More From Technology and Less From Each Other. A robot, in contrast, “is innocent of such capacity.” Upon seeing an elderly research subject speak warmly to a robotic baby seal named Paro—designed as a therapy tool for people with dementia—Turkle writes:

“Paro took care of Miriam’s desire to tell her story—it made a space for that story to be told—but it did not care about her or her story. This is a new kind of relationship, sanctioned by a new language of care. Although the robot understood nothing, Miriam settled for what she had.”

In contrast, ethicists who see potential for positive human-robot encounters argue that robotic assistance doesn’t have to come at the cost of human interaction. Just as science develops new drugs to treat conditions that don’t respond to existing medicines, these new tools may be a vital resource for people who struggle with traditional modes of communication.

Reactions to Stevie at Knollwood have been mixed. Some residents have been fascinated by the details of the robot’s construction, quizzing the Irish team on specifics and printing out reams of articles for their own reading back in their apartments. There’s also a small-but-vocal contingent who feel they’ve lived perfectly good robot-free lives so far and don’t see why they should be expected to change that now.

No matter how much comfort a robot provides, it won’t be widely adopted by the elder-care industry unless it provides value to the people purchasing it. Care homes are businesses, ones that face a stark economic crisis: the ever-growing gap between the demand for care and the workers available to provide it. Stevie and similar robots could be the savior the industry desperately needs. After all, unlike a human employee, a robot can be on its feet—well, its wheels—all day and all night, moving placidly from one room to the next, with the same level of energy and attention whether it's on its first hour of work or its twelfth.

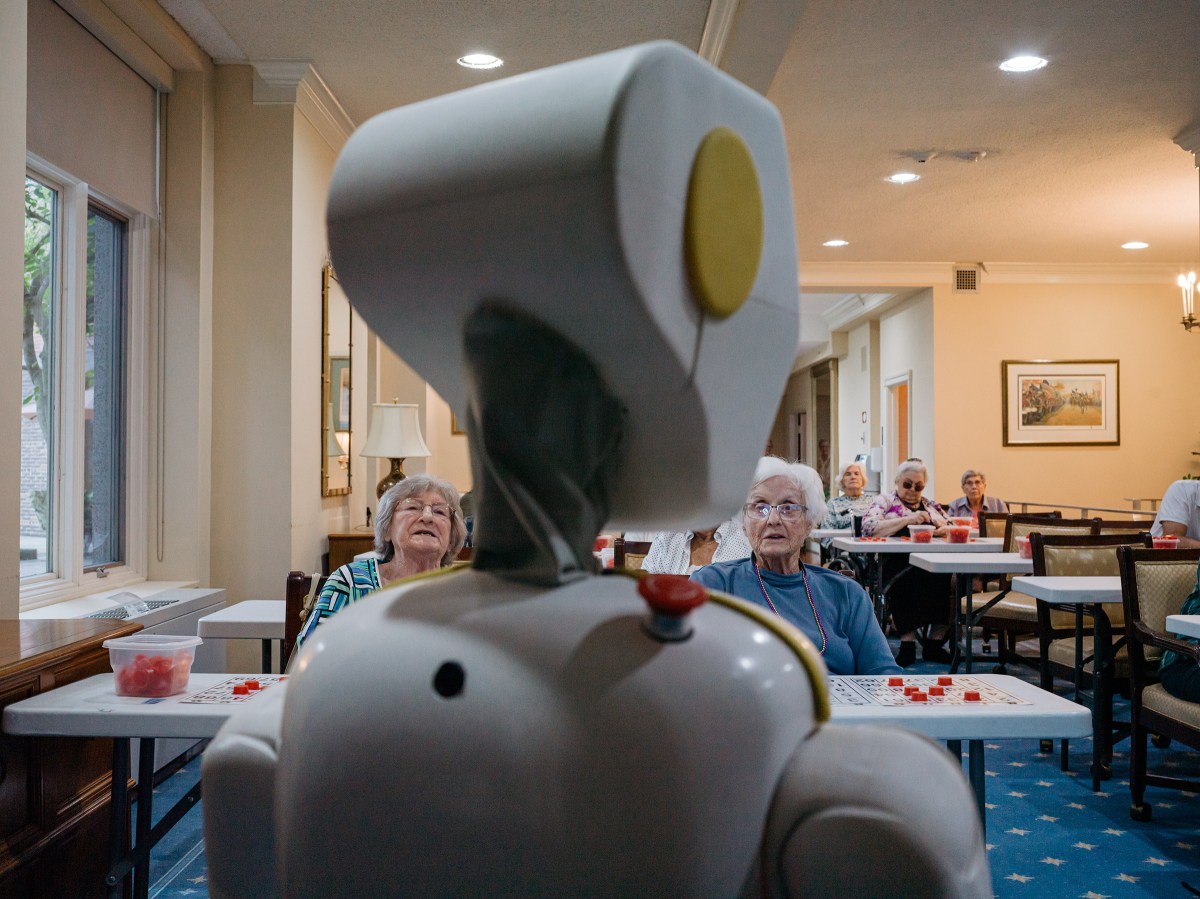

Stevie hosts Bingo night for residents. Greg Kahn for TIME

Stevie hosts Bingo night for residents. Greg Kahn for TIME Knollwood isn’t the only facility looking to technology to enhance its workforce. In 2018, the global market for robots designed to assist the elderly and disabled, including social robots, was $48 million. The market for rehabilitative robots, which include everything from Paro seals to robotic exoskeletons, was $310 million, according to the International Federation of Robotics, a Frankfurt-based trade group. The market for social robots is expected to grow 29% annually from 2019 and 2022, while demand for rehab robots is projected to grow 45% per year in the same period.

The current version of Stevie cost between €20,000 ($22,00) and €30,000 ($33,000) to make, and a retail version would likely be lower. At current market conditions, a monthly service contract for the robot—the sales model the Trinity team expects to take the market—would likely run between 50% and 60% of the cost of hiring a human to do the same tasks.

These characteristics make Stevie seem, to some current human caregivers, an unwelcome threat. “A lot of our staff, just like our residents, are intimidated by technology,” says Jessica Herpst, deputy director of operations and technology at the Army Distaff Foundation, the nonprofit that operates Knollwood. “The majority of our staff...work multiple jobs, are older women, sometimes older men, who speak English as a second language and work their butts off…they see this [as] competition.”

Neither Stevie’s creators nor Knollwood’s management want to displace human employees with an army of robots. The challenge is distributing the abundant work available in a way that benefits both the carers and the cared for.

“Sometimes I’ve seen nurses not even eat. They work all day,” said one Knollwood maintenance worker as he drove off the parking lot to start his second eight-hour shift of the day, this one as an Uber driver. “If they have enough robots to do the work, it could help a lot.”

Menbere Gebral is an activities assistant in the long-term care unit, and she adores her residents. They remind her of her late parents back home in Ethiopia. Making her residents happy is extremely important to her, and their weekly bingo game is very important to them, so when Stevie and his handlers showed up at a recent bingo session she was a little wary.

Stevie recharges his batteries as researchers take a break while testing the robot at Knollwood Military Retirement Community. Greg Kahn for TIME

Stevie recharges his batteries as researchers take a break while testing the robot at Knollwood Military Retirement Community. Greg Kahn for TIME “At first, I’m scared. I’m not lying to you,” she recounted a few days later. Normally Gebral spends bingo hour toggling back and forth between the laptop computer that calls out the numbers and the players seated at the tables, who need help with everything from placing the plastic caps on their bingo cards to adjusting their oxygen tanks. Dealing with a robot initially seemed like one more administrative task.

After one session, though, Gebral was a convert. Stevie called out the bingo numbers, freeing Gebral from the laptop program and leaving her able to interact with residents. Even with Stevie at her side, Gebral was on her feet and constantly busy during bingo hour. But she was busy with the parts of her job she likes best, and that most affect her residents’ well being. “I love it,” she said of the robot. “You know why I love it? It’s very helpful. When the robot [does] something, you [can be] up and helping the residents.”

Next year, the team will return to Knollwood with a new version of Stevie that’s currently under construction in the lab, with upgrades based on the research they’ve done at the facility this year. When the roboticists return to Dublin, the robot will stay behind in Washington for the staff to operate independently.

McGinn’s team is already speaking with other institutions interested in their own custom robot. After a pit stop back at the lab at Trinity, the current version of Stevie and the researchers will deploy to a care home in southern England for several weeks for a trial similar to the one at Knollwood. They are also in talks with a major nursing care company in Europe. Maybe the residents of homes in different countries and cultures will want entirely different things from Stevie than Knollwood has. Models for ongoing human-robot relationships are relatively few and far between, and every new community that invites the robot in will help define this new kind of partnership.

In the end, “YMCA” did make the set list of the karaoke concert. Soriano led the audience through the lyrics while Stevie’s arms swiveled around in the best approximation of the dance moves its custom programming could allow. It was no Village People. It didn’t matter. The audience was happy.