By David von Drehle, with Aryn Baker / Liberia

On the outskirts of Monrovia, the capital of Liberia, on grassy land among palm trees and tropical hardwoods, stands a cluster of one-story bungalows painted cheerful yellow with blue trim. This is the campus of Eternal Love Winning Africa, a nondenominational Christian mission, comprising a school, a radio station and a hospital. It was here that Dr. Jerry Brown, the hospital’s medical director, first heard in March that the fearsome Ebola virus had gained a toehold in his country. Patients with the rare and deadly disease were turning up at a clinic in Lofa County—part of the West African borderlands where Liberia meets Guinea and Sierra Leone. “It was then that we really started panicking,” says Brown.

Even in ordinary circumstances, the doctor’s workday was a constant buzz of people seeking answers: Can you help with this diagnosis? Would you have a look at this X-ray? What do you make of this rash? Inevitably, Brown would raise his eyebrows and crease his forehead as if surprised that anyone would think he might know the answer. Just as inevitably, he would have one.

Ebola was different. On this subject, Brown had more questions than answers. He knew the virus was contagious and highly lethal—fatal in up to 90% of cases. But why was it in Liberia? Previous Ebola outbreaks had been primarily in remote Central Africa. Could the disease be contained in the rural north? The membrane between countryside and city in Liberia was highly porous; people flowed into Monrovia in pursuit of jobs or trade and flowed back to their villages, families and friends. “Sooner or later,” Brown remembers thinking, “it might reach us.” And what then? A poor nation still shaky after years of civil war, Liberia—population 4 million-plus—had just a handful of ambulances in operation. How could Liberia possibly deal with Ebola?

(Read the Ebola Doctors’ Stories)

Because he couldn’t answer these imponderables, Brown focused on what he could do. At a staff meeting, he assigned Dr. Debbie Eisenhut, an American with Serving in Mission (SIM), to research the disease. By combing the Internet, Eisenhut found what little there was to know about Ebola virus—symptoms, modes of transmission, treatment options. In its early stages, Ebola looked like any number of human infections common in that part of the world, including malaria: fever, achiness, a general sense of malaise. By the time it produced more shocking symptoms—uncontrollable vomiting, torrential diarrhea, organ failure and sometimes bleeding—the patient’s chance of survival was small.

The best news Eisenhut found was that Ebola virus does not pass through the air; transmission requires direct contact with the body fluids of symptomatic patients. As for treatments, her findings were meager: fluids to stave off dehydration and Tylenol for pain. And to prevent its spread, chlorine bleach solution to disinfect skin, clothes, bedding and floors. There was no known cure.

Eisenhut’s findings made it clear that Ebola patients must be separated from the rest of the hospital population and treated by staff wearing protective gear. And this posed further questions for Brown. The Eternal Love Winning Africa (ELWA) hospital didn’t have an isolation ward, nor was there time or money enough to build one. No hospital in Liberia had one. Looking around the compound for a solution, Brown’s eye settled on the modest chapel, bare but for a few battered wooden pews and a lectern that served as a pulpit.

“Well, of course, turning the chapel into an Ebola unit was not welcomed by the staff of the institution. The bulk of them said, ‘Why should we turn the house of God into a place where we put people with such a deadly disease?’ And some said, ‘Where will you provide for us to worship in the morning?’” Brown recalls. (His story, like all the accounts quoted here, was shared in an interview with TIME.)

Read More: The Ebola Nurses’ Stories

Dr. John Fankhauser, another volunteer, a family physician from Ventura, Calif., had a ready answer to those objections. Jesus himself treated patients in the house of God, Fankhauser noted. Still, the idea remained unpopular, so Brown tried a more personal brand of persuasion. One by one, or in small groups, he asked the upset hospital workers, “What if you get sick with Ebola, or a member of your family? If the ELWA facility is not prepared to treat patients, where will you go?” Eventually, as Brown recalls, “a couple of them saw reason.”

Brown arranged for staff training and stockpiled bleach. Eisenhut took charge of the chapel conversion, assisted by Dr. Kent Brantly, a physician from Texas who had moved to Liberia with his family as part of the Christian relief group Samaritan’s Purse. The doctors found room for six beds, which seemed like plenty, because they assumed that Liberia’s Ministry of Health would eventually create a proper Ebola treatment facility. The chapel would be needed only as a safe place to hold infected patients while they awaited test results and transfers.

Vast and tragic questions lie behind that mistaken assumption. The Ministry of Health did virtually nothing. Why did it fail to take timely action? And why was the failure replayed in Guinea and Sierra Leone? Why weren’t these governments encouraged and supported by international watchdogs like the World Health Organization (WHO)? Why were so many officials from Washington to Geneva to Beijing unable to see what Brown could see, unable to prepare as he prepared? Why didn’t the news from the borderlands produce immediate official action in March, when the worst Ebola epidemic in history—by far—might have been contained and snuffed out?

Why, in short, was the battle against Ebola left for month after crucial month to a ragged army of volunteers and near volunteers: doctors who wouldn’t quit even as their colleagues fell ill and died; nurses comforting patients while standing in slurries of mud, vomit and feces; ambulance drivers facing down hostile crowds to transport passengers teeming with the virus; investigators tracing chains of infection through slums hot with disease; workers stoically zipping contagious corpses into body bags in the sun; patients meeting death in lonely isolation to protect others from infection?

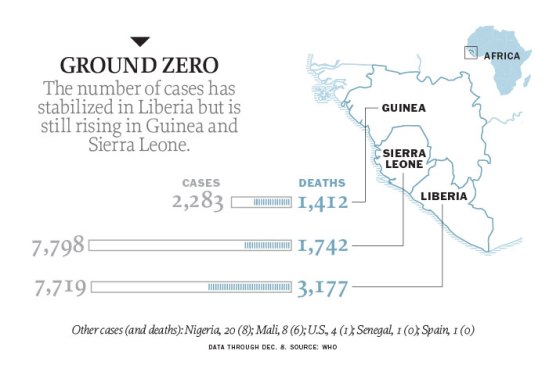

According to official counts, more than 17,800 people have been infected with Ebola virus in this epidemic and more than 6,300 have died since this outbreak’s first known case in rural Guinea in December 2013. Many on the front lines believe the actual numbers are much higher—and in any event, they continue to rise steeply. The virus has traveled to Europe and North America, where the resulting fear exceeded any actual threat to public health. In West Africa, however, the impact has been catastrophic. The number of Liberians with jobs fell by nearly half as businesses and markets closed in fear of Ebola. Sierra Leone’s meager health care network simply collapsed: Ebola patients were told by the government to stay home rather than look for a hospital bed. In Guinea, the epidemic stoked distrust of government and aid workers. Medical missionaries were driven from villages by violence and threats.

According to official counts, more than 17,800 people have been infected with Ebola virus in this epidemic and more than 6,300 have died since this outbreak’s first known case in rural Guinea in December 2013. Many on the front lines believe the actual numbers are much higher—and in any event, they continue to rise steeply. The virus has traveled to Europe and North America, where the resulting fear exceeded any actual threat to public health. In West Africa, however, the impact has been catastrophic. The number of Liberians with jobs fell by nearly half as businesses and markets closed in fear of Ebola. Sierra Leone’s meager health care network simply collapsed: Ebola patients were told by the government to stay home rather than look for a hospital bed. In Guinea, the epidemic stoked distrust of government and aid workers. Medical missionaries were driven from villages by violence and threats.

Read More: The Ebola Caregivers’ Stories

Ebola should not have been a surprise. The steady expansion of human habitat brings people into contact with remote reservoirs of poorly understood diseases, and mobile populations allow pathogens to infect large numbers in a short time. The story of Ebola is the story of SARS, of MERS—and most of all, it is the story of HIV and its nearly 80 million victims, roughly half of whom have died. All are animal-borne viruses that crossed to humans; HIV and Ebola even come from the same region of Central Africa.

But lessons are easily forgotten, it seems, in the face of feckless African governments and complacent Western powers, rival healers and turf-guarding bureaucrats. National and global health authorities would wait five months beyond March to acknowledge the unfolding disaster. Health ministries would ignore the warnings of doctors who were seeing the hot zone firsthand. WHO would initially rebuff efforts by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to help. By the time the authorities woke up, the epidemic was galloping away from them.

There will be time, when the still-raging epidemic is finally conquered, to dissect the failures. For now, consider the stories of individuals who stood up to Ebola and, by doing so, raised hopes that victory is possible. In the memorable words of an essay by one volunteer, Ella Watson-Stryker, they found themselves “fighting a forest fire with spray bottles.” They did not give up.

A Hostile Welcome

While ELWA was gearing up in March, across the border in Guinea the Ebola crisis had galvanized the group Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). The nearest modern medical facility to the original outbreak was an MSF clinic in Gueckedou intended primarily to treat malaria. In February patients began arriving at the clinic with high fevers.

Clinic doctors flashed word to MSF headquarters in Geneva. Alarmed, the higher-ups dispatched a small team of investigators to bring back blood samples for testing. “We thought it could be Lassa fever,” the organization’s president, Dr. Joanne Liu, recalls. Like Ebola, Lassa can cause pain and bleeding. Unlike Ebola, Lassa was known to be common in West Africa. Though somewhat less deadly, Lassa is still a matter of grave concern. Even before the test results were back, MSF assembled a sort of infectious-disease SWAT team to head off an epidemic. Watson-Stryker, a veteran public-health educator, got the call at her apartment in New York and within days was on a jet to Geneva for briefings.

While changing planes, she checked her phone and learned that the lab results were back and the samples contained Ebola. “Very briefly, I thought about getting back on the plane and going back to New York,” she says, but she continued on to Geneva with her mind unspooling “the graphic movie version of Ebola, of people bleeding from their faces.”

At headquarters, Watson-Stryker’s fears were tempered by MSF doctors who had dealt with earlier Ebola outbreaks. She set off for the forest of Guinea as part of a team that would not only treat patients but also trace their contacts and educate their families and neighbors on the nature and prevention of the disease. The team would also try to get a picture of how widespread the problem might be.

Their two-car convoy jounced and slogged for two days over bad roads to reach the clinic in Gueckedou. “When we got there, the tiny crew of people who had been handling everything were very happy to see us,” Watson-Stryker recalls. “One of the women—she was in charge of the project—I don’t think anyone has looked that happy to see me ever in my life. They were really exhausted.” Other aid organizations in the region were evacuating their staffs, according to Watson-Stryker; only MSF was expanding.

Arguably the most effective—and inarguably the cockiest—medical-relief organization in the world, MSF is a global movement pledged to deliver quality care to patients in remote and troubled places. The group, which was honored with the 1999 Nobel Peace Prize, is fiercely independent, with the vast majority of its budget coming from private donations. In 2013, MSF amassed more than $1 billion globally. Having a large and unrestricted revenue stream allows MSF to shun red tape and to speak honestly about conditions in the places where its medics venture. The organization is often among the first and loudest reporters of bad health news that local officials would prefer to keep quiet.

Read More: The Ebola Scientists’ Stories

Being effective did not guarantee a warm welcome, however. The MSF team encountered a local population hostile to outsiders. After decades, even centuries, of strife and misrule, the civil fabric of Guinea was badly frayed, and now this mysterious disease fired all sorts of rumors. Guineans could not help noticing that the foreigners and the Ebola virus had entered their lives almost simultaneously. “You saw the fear in people’s faces. They didn’t understand what was going on,” Watson-Stryker says.

And the scene around Gueckedou was indeed unsettling. On land near the clinic, construction crews were pouring concrete floors for tents to be filled with Ebola patients who had yet to materialize. Figures clad head-to-toe in waterproof protective suits, bug-eyed in goggles, went house to house with sprayers pumping who-knows-what onto the ground from tanks on their backs. It was chlorinated water to kill the virus, but some locals concluded that MSF workers were in Gueckedou to kill them. A young driver employed by MSF told Watson-Stryker that his father had stopped speaking to him because he was involved with the clinic. More than once, her car was stoned. As she approached one home, the man of the house emerged holding a knife that he tapped menacingly against his thigh.

Thwarted by rampant suspicion, Watson-Stryker hired local Guineans as her eyes and ears, sending them into villages to get a sense of the outbreak’s impact on people so she could help prepare for local interventions. They would talk and listen with village leaders, often returning with alarming reports. “There’s a lot of sick people in that village,” one might say.

By this careful but urgent process, the MSF team determined that something new and dangerous was going on in the borderlands. Previous Ebola outbreaks had been isolated in a single area, but now the virus was widespread. As MSF’s Liu puts it, “Already there were multiple locations of clusters” up to 100 miles (160 km) apart. In raw numbers, the Ebola outbreak might have seemed small compared with the chronic contagions of cholera and malaria in West Africa. But an epidemic of Ebola, with its ghastly effects, could corrode civil society by spreading panic. The disease leaped to the top of MSF’s priorities.

But few officials wanted to hear it. Liu recalls fruitless conversations in March with ministries of health in the region, “pushing them and telling them that this was going to be different.” Again and again, health officials complained that the doctors—not the disease—would panic the populace. “We were quickly told by a variety of agencies that we were crying wolf,” Liu says.

One skeptic—perhaps the most influential and thus the most disastrous—was WHO, the health arm of the U.N. Underfunded and overly bureaucratic, WHO is, in the eyes of its many critics, woefully inadequate in dealing with rapidly emerging threats like Ebola. Worse perhaps, the agency’s local representatives are notoriously jealous of their turf and prerogatives. At this same critical moment, WHO offices in West Africa turned away a team of experts from the CDC working in Guinea, insisting that their help was not needed, says CDC director Dr. Thomas Frieden. The CDC, a large and very well-regarded public-health agency, is unsurpassed in its capacity for action, maintaining some 2,000 field workers in 60 countries around the world. Those workers in turn can often summon resources from the U.S. to smother epidemics in their infancy abroad.

Teamwork at this early moment might have saved thousands of lives and ultimately billions of dollars in direct and indirect costs stemming from the Ebola epidemic. Instead, WHO closed the door, says Frieden.

The CDC would be back in the summer, when Ebola was running wild, to train local volunteers in the crucial techniques of tracing and evaluating the contacts of Ebola patients. By then, however, the challenge would be incalculably greater.

Frieden says he intervened personally with WHO’s top leadership. “I had to get directly involved,” he explains, telling his counterparts, “Let our team in. This is ridiculous.” (A spokesperson from WHO told Time that “no one in Geneva knows of anything regarding CDC” being asked to leave Guinea in March.) The CDC specialists believed they had a chance to control the epidemic if they worked with local health authorities and other groups in the region. But Frieden’s protests changed nothing. “They wanted to do it themselves—there was resentment.” Summing it up, he says, “WHO didn’t want us there, so we left.”

In Monrovia, Jerry Brown found himself wondering if he had converted the hospital chapel in vain. April turned to May, and still Ebola had not reached the capital. There was one close call: an infected traveler from Lofa County commuted through the city on her way to the town of Harbel, where she died. But Dr. Mosoka Fallah, a Harvard-educated Liberian epidemiologist, rushed to the home of the taxi driver who had picked up the traveler and persuaded him to accept a 21-day quarantine. The three weeks passed—the full incubation period for Ebola—with no new signs of disease. Monrovia remained untouched.

Brown contacted the Ministry of Health in early June to ask if he should dismantle ELWA’s isolation unit. The official who took his call suggested waiting a few more days, just in case.

On June 12, after a late evening in surgery, Brown emerged from the operating room to find a string of missed calls on his cell phone. Ringing back, he reached the same official, who asked if the chapel facility was still ready. Two patients, visitors from Sierra Leone who were staying in New Kru Town, an area populated by immigrants, had turned up at the government-run Redemption Hospital in Monrovia with suspicious symptoms. Medical staff examined them without protective gear. “They most likely have Ebola,” the ministry official said, according to Brown. “And the only place I thought about that we could keep them until we have an investigation done is at your center.”

Brown dreaded the impact of welcoming Ebola into his hospital, but he felt he had no moral choice but to absorb it. He knew his fellow doctors would stand with him, but the nurses were another matter. They initially refused to mix disinfectant and don protective gear for the work unit. “If you want my resignation, I will give it to you,” one told Brown. “I would rather leave than attend to an Ebola patient.” Another nurse said she felt too sick to stay at work. “I developed a headache a couple of minutes ago,” she said.

With all their work thus far at stake, the doctors tried personal appeals to their favorite nurses. Brantly circled around to the nurse with the headache, and after a little cajoling, she agreed to work in the isolation unit—but not alone. The doctors continued to plead with staff until they found a nurse’s aide and an operating-room technician willing to suit up.

Covered head to toe in Tyvek gear, goggles and masks, this cobbled-together team was ready when the ambulance from Redemption pulled into the ELWA compound two hours after the official’s call. Brown was shocked to see the ambulance crew dressed in ordinary scrubs.

One of the patients lay dead inside the vehicle. Brantly rushed the other patient into the chapel; that patient died a couple of days later, according to Brown. A nurse from the ambulance was likewise doomed, along with a doctor who did the initial screening at Redemption. Ebola had reached the city.

But it was even worse than that, as the Liberian epidemiologist Fallah quickly came to understand. He knew that an epidemic is not a simple matter of the sick people you can see. Even more important is the web of individuals who touch the sick or are touched by them. To control a contagion, it’s not enough to treat the visible patients; you must find and contain every strand and tendril of the web.

Fallah retraced the steps of the patient who died in ELWA’s chapel to a house in the Monrovia slum of New Kru Town, home to many Sierra Leonean immigrants, where he encountered “a strong feeling of denial” about the virus. One woman he approached gave a typical reply: “If anyone says they have Ebola in this house, I will give you a slap.” To acknowledge the disease was to invite social stigma and financial ruin.

“This was a six-bedroom house, but in New Kru Town, typically every room is a household,” Fallah says. “And we were counting between five to 10 or so in a room. So we’re looking at between 30 to 60 persons.”

Through dogged investigation, Fallah soon learned the identity of the person who drove the patients to Redemption Hospital and confirmed that the driver’s sister was dead of the disease. He learned that the driver had disappeared. And he determined that those contacts had other contacts—the strands of a web that Fallah followed until he discovered the identity of a contact who had been vomiting in the street. Yet other contacts (his heart fell when he realized this) had visited “a communal bathroom that all the houses use.”

This is a classic example of contact tracing, and it’s critical to fighting infectious disease. Watson-Stryker and others were doing much the same thing in Guinea and Sierra Leone. The network of contacts that Fallah unearthed revealed that Ebola had been simmering in Monrovia for some time. “Things were going on that we didn’t know about,” he says. “People visiting clinics. Some of them went to the church.” But none of it had been reported. Fear, shame and ignorance combined to keep Ebola shrouded. This was a terrible revelation, says Fallah. “It blew our minds.”

A Chain Reaction

Ebola’s lurking presence in the capital gave it a head start once it revealed itself in mid-June, and Monrovia’s fragile patchwork of health care providers was quickly overwhelmed.

The meltdown began in early July at Redemption, a single-story structure painted swimming-pool green and blazoned with murals that explain the importance of personal hygiene and antimalarial mosquito nets. Redemption Hospital’s lack of preparation ignited a chain reaction of infection and death: a nurse, a doctor, a medical aide. Frightened staff members vanished from their posts, forcing the hospital to close temporarily at a time of desperate need.

Other health workers at other clinics quickly followed. (Brown and his colleagues somehow managed to keep ELWA functioning.) Institutions that might have taken up some slack as clearinghouses for information to fight the epidemic—schools and government offices—also began shutting down, and many senior bureaucrats fled the country. President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf appeared stunned, frozen in place, unable to declare an emergency until seven weeks after the Redemption disaster. It was alarming how rapidly the yoked contagions of virus and fear unhinged Monrovia.

Within days of the June 12 call, ELWA’s six-bed chapel was overwhelmed. The Ministry of Health scrambled to create a rudimentary 20-bed Ebola treatment unit (ETU) at the state-run John F. Kennedy Hospital, and the new facility was beyond capacity almost as soon as it opened. At least two dozen people died in Monrovia in the early days after Ebola’s arrival.

More beds were needed. Brown decided to convert the brand-new kitchen and laundry building donated by Samaritan’s Purse. An emergency check from the organization, which was founded by the Rev. Franklin Graham—son of the evangelist Billy Graham—provided for building materials and more protective gear. Samaritan’s Purse also sent its director of disaster response, Dr. Lance Plyler, to join the battle. Hastily completed in July, ELWA 2, as the facility became known, had room for an additional 20 beds.

Still, it wasn’t enough. “Within a week it was filled,” Brown says. “People were now in the corridors, under the eaves of the building. Patients were just pouring in on a daily basis.”

Brown and Brantly had agreed early on that Brantly would handle the Ebola cases while Brown kept the rest of the hospital going. As July crept along one wretched day after another, matters became so chaotic at ELWA that Brown didn’t immediately notice when Brantly went missing from the treatment unit. When, late in the month, he noticed and asked for an explanation, Dr. Fankhauser broke the news that their colleague was feverish and had put himself in quarantine at home.

Evidently, Brantly had been exposed to the virus while performing triage in ELWA’s emergency room. During an overnight shift, a woman brought her suffering mother into the ER for help. Brantly wore a gown, gloves and face mask but not the full protective suit, because the suit “scares people, and they won’t necessarily tell you the truth,” he explains.

During the examination, the woman’s mother needed help from her daughter in making an urgent trip to the bathroom. Brantly suspected Ebola. He took the woman aside to explain why her mother needed to go to the ETU. “I had to counsel her extensively to reassure her that we were trying to do what was best for her mother—we were not abandoning her,” the doctor says. “I took off my mask, gloves and apron when I talked to her, and I probably held her hands or put my arm around her shoulder, as I often do.” Brantly doesn’t think he was infected by the mother. But the daughter had taken her to the toilet, and there’s a chance she hadn’t washed her hands afterward.

There was more bad news for Brown. On July 26, ELWA’s personnel coordinator, Nancy Writebol—a medical aide from North Carolina who worked with Serving in Mission—tested positive for Ebola. Within a few days, two other employees had been infected. Once again, Brown had to talk his way through a possible staff walkout.

It was late July now, and Ebola had pushed Jerry Brown and his hospital to its breaking point. On a personal level, he was now forced to do something he had promised his wife he would not do: suit up in Tyvek and go to work in the ETU. Every willing hand was needed, and the fearful staff must see that the boss had enough courage to do as much as he asked of them, he says.

Brown also made a painful decision to close the main hospital for a few days and limit some services after that. Though malaria season was coming on and expectant mothers counted on ELWA for childbirth, Brown felt he had no choice. Not after one of his own nurses, down with Ebola, was turned away for want of a bed.

Anatomy of a Virus

In his white lab coat and eyeglasses, Dr. Bruce Ribner looks nothing like a biblical patriarch, but for many years he felt like Noah building his ark. As medical director of the Serious Communicable Disease Unit at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, Ribner began work in 2001 on a meticulously safe and secure facility where patients suffering from lethal contagious diseases—like Ebola—could be treated with minimal risk. At the time, the only remotely comparable unit in the U.S. was a locked room, nicknamed the Slammer, at an Army research lab in Maryland.

Ribner built his safety pod at a time when few others could see a need for it. “The unit was open for 12 years, and we had all of two activations—which both turned out to be negative,” he recalls. His critics asked whether the money spent to maintain the unit and train and drill the staff was being wasted. Even Ribner came to think of his creation less as a vital part of a working hospital than as “an insurance policy.”

Then, on Tuesday morning, July 29, his unit received a visit from “some government people” who took a look around but said little. The next day, Ribner’s telephone rang. The government people wanted to know if Emory could receive an American Ebola patient from Liberia.

“Of course!” the doctor replied. “That’s what we’re in business for. If you get them here, we’ll take care of them.” After hanging up, Ribner realized that he should let hospital management know that Ebola was on its way to North America.

The Ebola virus (Zaire strain) was discovered in 1976 by Belgian microbiologist Dr. Peter Piot, but it entered the broader American consciousness only in 1995, through the runaway success of Richard Preston’s The Hot Zone. Preston’s book told the somewhat hyperbolic story of a mysterious disease (and its cousin virus, Marburg) among lab monkeys at a facility in Reston, Va. The cause proved to be a new strain of Ebola that, thankfully, was harmless to humans. Though the Reston crisis faded, no one who read Preston’s descriptions of viruses spreading invisibly through passenger jets or terminal patients bleeding from every orifice ever entirely lost their dread of Ebola.

By coincidence, the virus caught the attention of America’s national-security apparatus at about the same time. In the early ’90s, a defector from the former Soviet bioweapons program testified before Congress that his government had been studying Ebola as a possible weapon.

Chastened, the Department of Defense accelerated their own research. For Thomas Geisbert, a scientist at the U.S. Army’s high-security USAMRIID infectious-disease lab in Maryland, this was a career-making development. Having made Ebola his virus of choice, he became a point man on a very important pathogen almost overnight. And when 9/11 brought home the potential danger of Ebola in the hands of terrorists, Geisbert’s research budgets grew again. He focused on developing drugs to attack the virus, one of which eventually became something called TKM-Ebola, as well as a vaccine. Still, despite remarkable results in monkeys, “that’s where it stopped,” Geisbert says. There wasn’t money or interest from drug companies to “take those products across the finish line.”

Over the years, he and other Ebola scientists made progress in understanding the roles played by each of the virus’s seven structural proteins in capturing certain human cells and converting them into Ebola-replication factories. Why does Ebola do this? It has no reason: a virus is not even a life form. It’s like a gear that by itself can’t accomplish anything. But when it drops just so into a larger machine, the machine becomes an accomplice and begins cranking out copies of the gear.

The sole purpose of one of Ebola’s proteins, the glycoprotein (GP), is to distort the immune response in primates. The Ebola GP can take two forms, one of which is good at binding to and disintegrating so-called sentinel cells whose job is to raise the alarm about invading agents like Ebola. At the same time, another viral protein shuts down the immune system’s ability to produce interferons, which normally act as potent virus killers. As Ebola continues to replicate and thwart the immune defenses, it launches into the blood to reach critical infection-fighting tissues like the lymph nodes. The result: sky-high fever, agonizing aches and pain, deluges of vomiting and diarrhea—all of which can send the body into shock. Dehydration, low blood pressure, electrolyte imbalances and organ failure all may contribute as causes of death. Basically, Ebola tricks your body into surrendering itself.

When Dr. Pardis Sabeti, an Iranian-American geneticist at Harvard, was 19, she read Preston’s book and said, “Oh wow, I want to do that!” she recalls. Her chance came in March. After years of working with lab samples of Lassa and Ebola, she and her team were presented with boxes of blood in vials, fresh from patients in West Africa. By sequencing the genome of each virus sample, Sabeti and her team were able to track small mutations in the virus from one patient to the next.

This work proved highly valuable because it ruled out the possibility that the disease was being spread through repeated contact with infected animals. Instead, it was moving from person to person. Her conclusion gave an added boost to the strategy of tracing patient contacts to corral the epidemic.

Unfortunately, the genome revealed no magic bullet to fire at the heart of Ebola, which ended up killing one of Sabeti’s colleagues, Dr. Sheik Humarr Khan. Khan, a storied researcher and physician in Sierra Leone, died in July after getting infected while treating Ebola patients.

Brushes with Death

What is it like to die of Ebola? Foday Gallah came close enough to know. A gregarious man with a level gaze, Gallah ran an ambulance in Monrovia, an exhausting and traumatizing service. Ebola has no power that he has not witnessed many times. His own infection came on the day that he saved a little boy’s life.

Gallah’s ambulance was summoned in early September to the home of a large family who had all been exposed to Ebola. He found the mother and two of her children wretchedly symptomatic. Gallah eased them into his vehicle but left the rest of the family behind. With beds in short supply, hospital staff would surely send away the ones without symptoms.

Soon, he was called back to that house. “When I got there, it was the grandmother, the father and the two sons. They were dehydrated. They were weak.” All four would die, just like the first three family members he transported. This left one small child all alone.

Gallah urged the neighbors to call him the moment the child showed symptoms. He remembers the ringing of his phone. “When I got there, the boy was lying in a pool of vomit,” he recalls. “He’s a 4, 5-year-old child, right? Very dehydrated and weak. He couldn’t move.”

In a rush, Gallah donned his protective gear and scooped up the boy, who immediately vomited all over him. “Maybe there was an opening somewhere that I didn’t know,” he suggests. Thanks to Gallah’s efforts, the boy eventually recovered, but within days of the rescue, Gallah’s temperature rose. Then the pain hit. “I had headaches before, but the headaches of Ebola, they don’t break,” he says. “You take some ibuprofen to cool it down and it escalates.

“I have never experienced anything like I experienced with Ebola,” he continues. “Ebola pain, it don’t stop. It makes you want to give up. I used to be a strong man, and this just broke me down.”

Salome Karwah, then a trainee nurse at her parents’ modest medical clinic near Monrovia’s airport, suffered the same excruciating headaches when her whole family came down with Ebola after an infected uncle sought her father’s medical care in late August. But that was nothing compared with the agony of watching both parents die in front of her at the MSF-run Ebola treatment center. “I went out of my mind for about one week. I was going mad. I just felt that everything is over.” Karwah and her sister survived.

Soon after, MSF was looking to employ Ebola survivors in the treatment center. Scientists stop short of saying for certain that Ebola renders a person “immune” if he or she survives—but that’s their suspicion. There’s not one known case in the decades since Ebola was discovered of a person contracting the disease more than once. So when MSF asked, Karwah was one of the first to step forward.

“The first day I came here for an interview, I saw people carrying bodies. I started crying. I told my friend, ‘I can’t make it.’ But when I went the next day I said, ‘Sitting and crying won’t help me. So it’s better I go and work. The more I interact with people, the more I will forget about my sad story. So I decided to make myself very much busy to help others survive.”

For Kent Brantly, near death in late July, the worst part was the helplessness. “Ebola is a humiliating disease that strips you of your dignity,” he says. “You are removed from family and put into isolation where you cannot even see the faces of those caring for you due to the protective suits—you can only see their eyes. You have uncontrollable diarrhea, which is just embarrassing.”

With his temperature high, his heart racing and fluid collecting in his lungs, Brantly lay in his room at the ELWA compound, just “trying to rest and not die” while awaiting transfer to Ribner’s unit in Atlanta. As his laptop played passages of Scripture set to music, words of the Apostle Paul settled on his ears: “For I am convinced that neither death nor life, neither angels nor demons, neither the present nor the future, nor any powers, neither height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God.” He clung to that hope like a lifeline.

As he was waiting, word came of an experimental drug called ZMapp, developed by Canadian scientist Dr. Gary Kobinger. Like Geisbert’s TKM-Ebola, the drug showed promise in primates but had never been tested on humans and therefore hadn’t been approved for widespread use.

Unfortunately, Dr. Plyler from Samaritan’s Purse was able to get his hands on only enough ZMapp—three doses—to treat one patient. Aware that Nancy Writebol was in even worse condition than he, Brantly asked that the first injection be given to her. But then Brantly grew sicker, and Plyler worried that he wouldn’t survive the transfer. He decided to split the doses: Brantly would receive one injection and travel first; Writebol would receive two and go on the next flight. The hope being, of course, that this would sustain them long enough to get them to Emory University Hospital in Atlanta.

The Problem Turns Visible

On Aug. 2, near noon, a chartered jet with a specially designed biohazard unit inside began its final approach into Dobbins Air Reserve Base north of Atlanta. Inside was Brantly, so weak and febrile that he had barely been able to climb the short stairs onto the plane in Liberia. (Writebol would follow him three days later, in equally miserable condition.) Television cameras on the ground in Georgia fed live images of the landing to satellite trucks, which bounced the pictures to viewers around the world.

Geisbert, the Ebola scientist, now at the University of Texas Medical Branch, watched the scene on a TV set in Galveston with colleagues. It reminded him of O.J. Simpson’s white Ford Bronco—an otherwise mundane image packed with mystery and tension. A crisis that had been building for months was somehow encapsulated in that vehicle, for better or for worse.

Week by week through the summer, Geisbert had absorbed the enormity of the epidemic. Now signs of complete collapse were coming from West Africa. MSF saw them first. In June, the group issued a fresh warning that Ebola was “totally out of control.” Normally wary of bigfoot interventions, MSF now pleaded for action on a scale that only the Pentagon can provide. The warning was soon validated. On July 25, the virus was found in Freetown, the crowded capital of Sierra Leone. A few days later, Liberian President Sirleaf at last took action, closing her country’s borders and authorizing quarantines. On July 30, the Peace Corps pulled its volunteers out of infected West African countries.

Despite this litany of suffering, for many Americans it was the sight of that airplane floating downward, bearing their Ebola-stricken countryman, that finally brought home the pain. Walking to a waiting ambulance in his Halloween version of a space suit, Brantly carried the virus across the ocean—both real and psychic—that separates Fortress America from the sorrows of distant masses. Psychologists have shown that most humans feel the agony of an individual more intensely than the suffering of a large group. For many Americans, Brantly moved Ebola from abstraction to reality.

Read More: Ebola Directors’ Stories

Even an American who has given nine years of her life to Liberia felt it, though she was disgusted with herself for the feeling. “I think definitely when an American got Ebola, now it’s like, Anybody can get it,” says Katie Meyler, founder of the More Than Me Academy for the girls of West Point, a massively crowded Monrovia slum. “As messed up as that is and as frustrating as that is, I definitely was guilty of a little bit of that too.” But there was something good to be said for the reaction. “It became international news,” Meyler says, “and I think that’s when the fight was on.”

Frozen pipelines of international action began to thaw. Dozing bureaucracies stirred. Within days after Brantly’s evacuation, the World Bank pledged $200 million and the CDC jolted awake its emergency-operations unit, and on Aug. 8, WHO declared an emergency of international importance.

But as West Africans—and eventually the whole world—would learn, there was a lot of slack in the international response. The ringing of alarm bells in early August would produce in September a promise of U.S. troops to build treatment units and an unprecedented U.N. mission to attack the contagion. These steps would produce scouting trips several weeks later, followed by initial deployments. (The first U.S.-built ETU went online in early November.) A shocking projection by the CDC warned that without immediate and effective action, as many as 1.4 million people could be infected by January. And still the response moved as if through mud.

Joanne Liu of MSF grew so frustrated that she delivered a scathing attack at U.N. headquarters in early September, decrying the “coalition of inaction” that was permitting people to die by the hundreds in the streets of Sierra Leone. In response, Anthony Banbury was summoned to his boss’s office at the U.N. and ordered to lead the international Ebola mission.

A veteran of some of the largest famine-relief efforts in recent history, Banbury has a knack for both the logistics and the diplomacy involved in getting massive amounts of help to people with everything stacked against them: natural disasters, government corruption, nonexistent infrastructure. But he now says that nothing prepared him for the complexity of fighting Ebola. This was the first all-out international mission to fight an outbreak of infectious disease. There was no precedent.

Consider all that is needed: scores of small ETUs spread across thousands of square miles; trained doctors, nurses and support staff to operate them; diagnostic laboratories and the power sources to feed them; supplies to keep them going; food to replace the crops untended by dying farmers and farmers unwilling to work in groups to harvest; offices staffed by experienced diplomats to coordinate efforts among national governments, local governments, tribal leaders, NGOs and homegrown legions of Ebola fighters; and perhaps most of all, money—actual cash, not just pledges.

Fighting a virus is not the same as responding to an earthquake or a tsunami. Instead of a defined and visible problem, there is a mutating, invisible problem. Disaster relief deals with aftermath; this battle was ongoing. Eventually, the humanitarian efforts would begin to get traction, but never as quickly as the humanitarians hoped.

When Dec. 1 arrived—Banbury’s target date for getting the upper hand on the epidemic—he would have to acknowledge that the target would not be met. There was progress, but the number of people infected and killed was inevitably going to grow further. The failures of the official institutions to deal with Ebola in a timely way had doomed the effort to a long slog. “I’m proud of what we’ve accomplished so far,” Banbury ventures, “but in retrospect, the whole world wishes we had done more and we had done it earlier.”

Those Who Stand Up

In the killing heat of August, with Ebola uncontrolled, with no sign of help on the way from local or national or international cavalry, the time came for choosing. Who would run away? Who would stand and fight? The choice was deeply personal, one heart at a time.

Katie Meyler made the choice, along with Iris Martor, the nurse at More Than Me academy. Meyler, a tornado of energy, is a New Jersey native who set out for Liberia on a two-month mission and now considers it home. Martor has a tranquil face and—as time would show—reservoirs of courage behind it.

Like others in Liberia, the school colleagues learned of the Ebola outbreak in March. Martor recalls overhearing a heated conversation on a bus crowded with commuters. If there were 200 people on that bus, Martor estimates, 198 of them believed that the government was lying about Ebola in hopes of squeezing money from international aid groups.

The two women had no such illusions. Knowing the basics of Ebola and the nature of slum life, they feared that, as Meyler puts it, “if this ever got to West Point, it would be the end of Liberian existence. So many people live on top of each other. If 100,000 people get Ebola and they go out and spread it, it’s a threat to the existence of the Liberian people.”

A low and crowded labyrinth on the west side of Monrovia, on a peninsula that juts into the Atlantic like a thumb, West Point is home to at least 80,000 people, maybe more. The slum has no running water and virtually no electricity; a U.N. agency study in 2009 found just four public toilets serving a then estimated 70,000 residents. Living seven or more to each tiny room in makeshift shanties of corrugated metal and concrete blocks, the people of West Point are so densely packed that asking them to avoid close contact with other humans is like asking fish to avoid touching the sea. Ebola arrived in West Point on Aug. 12.

Meyler was home in New Jersey for a round of fundraising and a family vacation when she noticed a story in the morning paper. It was mid-August and West Point residents, furious about the establishment of an Ebola holding center in their neighborhood, looted the building one night and made off with potentially contaminated bedding. Concerned that the virus might spread out of control, President Sirleaf ordered the entire West Point section cordoned off on Aug. 19. The next day, the quarantined residents rioted. Soldiers fired on the crowd, killing a teenage boy.

The photo alongside the article featured one of Meyler’s students. She made her choice: “I took the next flight to Liberia.” She arrived to find Liberia in chaos. Schools and government offices were shuttered. Senior officials had fled the country. Ebola was everywhere: in the scenes of dying patients in bogs of waste outside the over-full hospitals, in the stench of the rotting dead awaiting burial crews, in the dread that hung over the city like a pall.

Meyler and Martor became Ebola fighters because there was no one else to turn to. Overnight, they converted the school into an ad hoc disaster-response center, holding meetings, organizing food distribution and even setting up an ambulance service for West Point with funds from a wealthy donor. “It’s like, we don’t have an organization if we don’t have students who are alive,” Meyler says. While she established a temporary orphanage and quarantine program for children whose families were in treatment or wiped out, Martor organized a team from the More Than Me school to visit the homes of every student. “Praise be to God,” she recalls, “none of them had gotten sick.”

But Martor realized their health was fleeting if the virus infected their neighbors. She went to Meyler with the suggestion that More Than Me sponsor teams of locals who could canvass as much of West Point as they could, house by house. Wearing boots and rain gear provided by the school, the “case finders” slogged through the muddy, viral streets. Martor’s team followed Meyler’s in their wake, keeping an eye out for developing Ebola cases but tending to other health issues in the community too. It was dangerous work because no one knew which houses were contaminated. “Don’t touch,” Martor instructed her nurses. “Don’t sit.”

Late in August, Martor’s infant daughter spiked a fever, followed by vomiting and diarrhea, and Martor was awash with fear that she had brought death into her own home. But it wasn’t Ebola, and the child recovered, leaving Martor to reflect on the risks she was taking and why she would do such a thing.

“Initially, I was afraid. I should admit that,” she says. “But then thinking and looking at it critically—if I don’t help, I will still not be free.” Ebola would pose a danger until it is stamped out, and why shouldn’t she be part of the effort? “If someone from America comes to help my people, and someone from Uganda, then why can’t I? This is my country. I should take the first step.”

The same spirit sustains Ebola fighters throughout West Africa. It was in the international team of researchers who chased the virus to its source in Guinea—five of whom died in the epidemic before their findings could be published. It is in the personage of Nelson Sayon, who ran a motorbike taxi service in Monrovia until Ebola. Like Meyler and Martor, he could have said no when the world fell short and left Ebola untended. But he said yes. “I volunteered myself to help my country,” he says, by joining a burial team run by the Liberian Red Cross.

His first day on the job, Aug. 2, Sayon collected more than 10 contagious corpses, some of them left for days in the heat. People threw rocks as his vehicle passed by. Everything and everyone associated with Ebola was being attacked; even Sayon’s parents were worried about his work.

In Maine, Kaci Hickox, an American nurse, stood up to fight Ebola, answering a September plea for experienced volunteers from MSF. Hickox had been dashing toward fires with MSF for years, but Ebola was something different, she says. “It’s one of those diseases that will infect an entire family and leave children as orphans and mothers without their children.” And it will kill health care workers for the smallest slip with protective gear or an IV needle. (More than 600 doctors, nurses and other medics have been infected in the epidemic so far, while more than 300 have died.) During the time she was in training with MSF, Hickox recalls, a worker at one of the group’s Ebola facilities was infected—a first for MSF—but not a single member of her class quit.

Deployed to Bo, Sierra Leone’s second largest city, Hickox stepped into a grueling routine. “International staff typically works 12-to-14-hour shifts six days a week,” she says. “It was in the high 90s when I was there and the suit is not breathable, because it’s made to not be absorbent. You can only be in the suit for about an hour because of the heat—but on days when we had 35 patients in the unit and maybe nine health workers, you have a very limited time to meet the patients’ needs.”

How can you properly comfort and encourage a patient who is moaning in agony when you’re peering through fogged-up goggles and shouting through a double mask? Fighting Ebola, in other words, means living with “such a terrible feeling,” Hickox says, a sinking, haunted sensation that no matter how much you’ve done, you could have done more.

Foday Gallah, the ambulance supervisor who saved a little boy’s life and nearly lost his own, recalled the fear he felt in choosing to stand up. But he says now that he really had no choice. “We have to do it. Nobody had come” to help, he says. “So we are the ones to pick up the cost. Fear was there, but it didn’t overtake us.”

Victory in Sight

The Ebola fighters have not yet won the battle. For every recorded infection, the CDC estimates that an additional 1.5 cases go unreported. And for every sign of progress against the epidemic, there is at least one sign that the crisis is not over. There are empty beds in ETUs around Monrovia today, with cases declining in Liberia as a whole. But Sierra Leone is failing to keep pace with its cases, and Guinea, scene of the original outbreak, isn’t in the clear yet either. But now Mali is scrambling to prevent the virus from running away. “I’m not that optimistic yet,” says Ella Watson-Stryker. “We still have cases coming in every day.”

Nevertheless, something significant has been accomplished in the fight against Ebola. The same Liberian clinics that were turning patients away in October, dooming them to die in misery on filthy plastic tarps, now have beds standing empty, unneeded. Two possible vaccines are on a fast track for widespread trials in the African hot zone. The time needed to test for Ebola is shrinking from days to minutes. The prospect of mass contagion moving into the U.S. and Europe has paled. In other words, victory appears possible, at the end of a clear, if difficult, path.

There is hope. And hope has proved to be the most potent weapon yet discovered against Ebola. With so much gruesome practice, doctors have learned a great deal about treating the disease, and survival rates are going up. Instead of visiting traditional healers, who became unwitting vectors of infection, more Africans are now going voluntarily into ETUs because they have seen survivors coming out. “Instead of saying, ‘If you get Ebola, you die,’ it became ‘If you report at the Ebola treatment unit early, you stand a chance,’” says Brown, the ELWA director. It is the faint light before dawn.

We are left with lessons to be learned, and the Ebola fighters can teach them. One has to do with readiness: there wasn’t any. Some of the poorest governments on earth weren’t ready for Ebola, and neither were the wealthiest. When a Liberian man named Thomas Eric Duncan arrived at a Dallas hospital with Ebola, he was sent home with antibiotics. When he returned, the hospital staff was inadequately protected. Infectious disease is a flash flood moving somewhere beyond the horizon. We must prepare for them while the sun is shining, because when the rain starts falling, it’s too late.

Another lesson has to do with the importance of having promising medical interventions ready to attack a virus before it spreads. Scientists have been working on Ebola for more than 20 years, but none made it to the drug-approval process because there was no incentive for pharmaceutical companies to mass-produce therapies that we might only need “just in case.”

For instance, Nancy Sullivan and Gary Nebel, virologists at the U.S. National Institutes of Health, have worked for more than a decade on an Ebola vaccine that was rushed into human trials in August. Two other vaccines aren’t far behind. And the companies behind the drugs ZMapp and TKM-Ebola are scrambling to produce enough doses for further trials.

Yet another lesson has to do with fear and suspicion. Americans didn’t throw stones at Ebola fighters or threaten them with machetes, as happened in West Africa, but New Jersey Governor Chris Christie did try to force Hickox into an unnecessary quarantine when she returned home. Dr. Craig Spencer, who volunteered with MSF in Guinea, was reduced to a political football on cable TV when he tested positive for Ebola upon his return. And Amber Vinson, a nurse who was infected while caring for Duncan in Dallas, was shocked to see her photograph on TV just hours after being diagnosed herself. She then endured the pain of reading hostile online comments while she suffered through her recovery from the disease.

And always, there is the lesson of gratitude for those who willingly, even eagerly, do the jobs no one wishes to do. Jobs that involve risking a horrible death on behalf of strangers who repay you with hatred. Jobs that involve exposing your heart to unfathomable grief. Jobs that involve giving your all while knowing that you will never feel it was enough.

Early in the epidemic, CDC director Frieden spoke of Ebola’s “fog of war.” Its shroud covers the battlefield. Eventually—though no one can say when—the Ebola fighters are going to be victorious. The fog will clear, leaving the hard truth in view: this won’t be the last epidemic. And when the next one comes, the world must learn the lessons of this one: Be better prepared, less fearful, less reactive. Run toward the fire and put it out together. Even more important, though, when the next one comes, remember the Ebola fighters and hope that we see their like again. —with reporting by Alexandra Sifferlin / Atlanta, Alice Park / New York City and Paul Moakley / Monrovia

Read more:

Why the Ebola Fighters Are TIME’s Person of the Year 2014

Runner-Up: Ferguson Protesters, The Activists

Runner-Up: Vladimir Putin, The Imperialist

Runner-Up: Massoud Barzani, The Opportunist

Runner-Up: Jack Ma, The Capitalist