Stanley Greene

The death of a poet

Stanley Greene wasn’t just a war photographer—a label he both embraced and despised. He was also a poet who always searched for dignity, justice and larger truths in every one of his photographs. A passionate lover of life, he defied death across the years, whether on the front lines or at home. But, after a long fight with cancer, one of America’s greatest photographers died Friday morning surrounded by his closest friends and colleagues. He was 68.

While he worked for many of America’s top titles—from The New York Times Magazine to Newsweek—he truly found a captivated audience in Europe, a continent that embraced his poetic ways, where documentary photography isn’t always just about communicating facts but also about conveying emotions and feelings—embodying life itself.

This passion for life was always within him. Born in 1949 in New York, he joined the Black Panthers in his teenage years and became an ardent anti-Vietnam War activist. His mentor, the great W. Eugene Smith, recognized this hunger for justice when Greene studied at the School of Visual Arts in New York, pushing the young man to channel it into photography.

And that’s what he did when he moved to California, where he covered and embraced San Francisco’s punk scene in the 1970s and 80s. “Suddenly I’m in an environment where 24/7 you live, bleed, drink, eat, screw, make art,” he wrote in Black Passport, his celebrated autobiographical monograph. “It was one of the best, most raucous, and at the same time most peaceful times of my life… It all started to merge and make sense, new sense.”

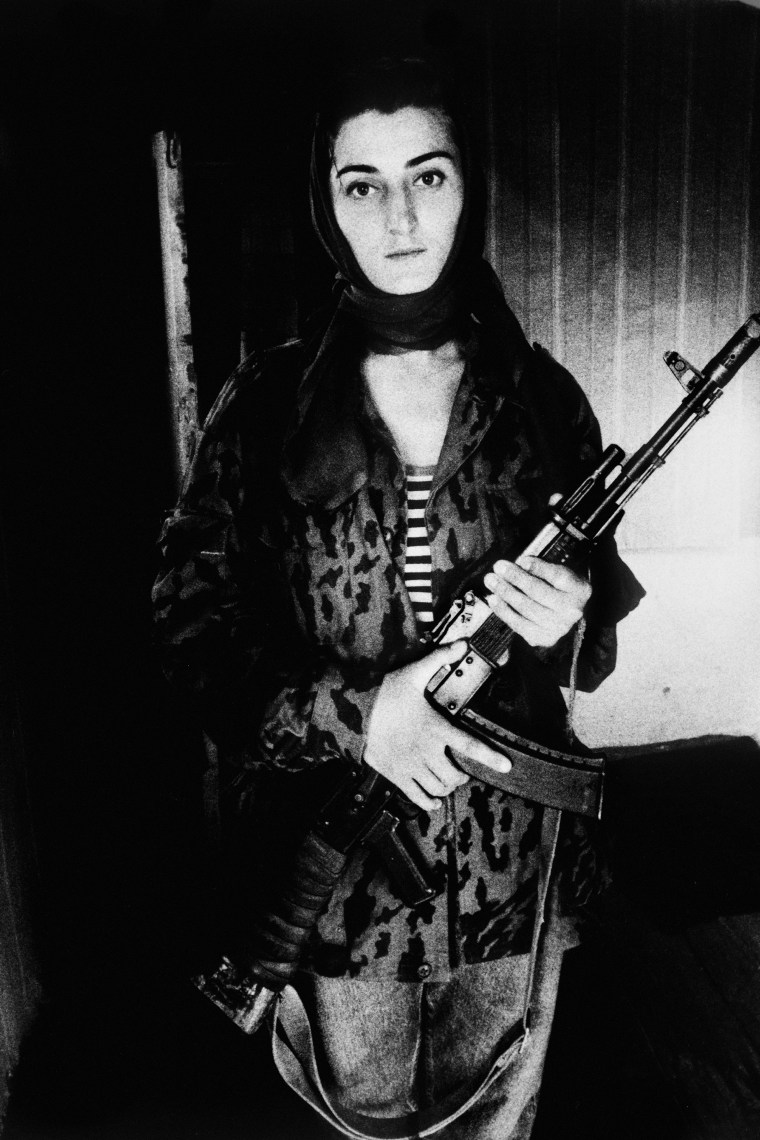

Asya, 22, a fighting nurse. “I fell in love with her. She was a fighter and maybe that was some bit of it.” Stanley Greene—NOOR

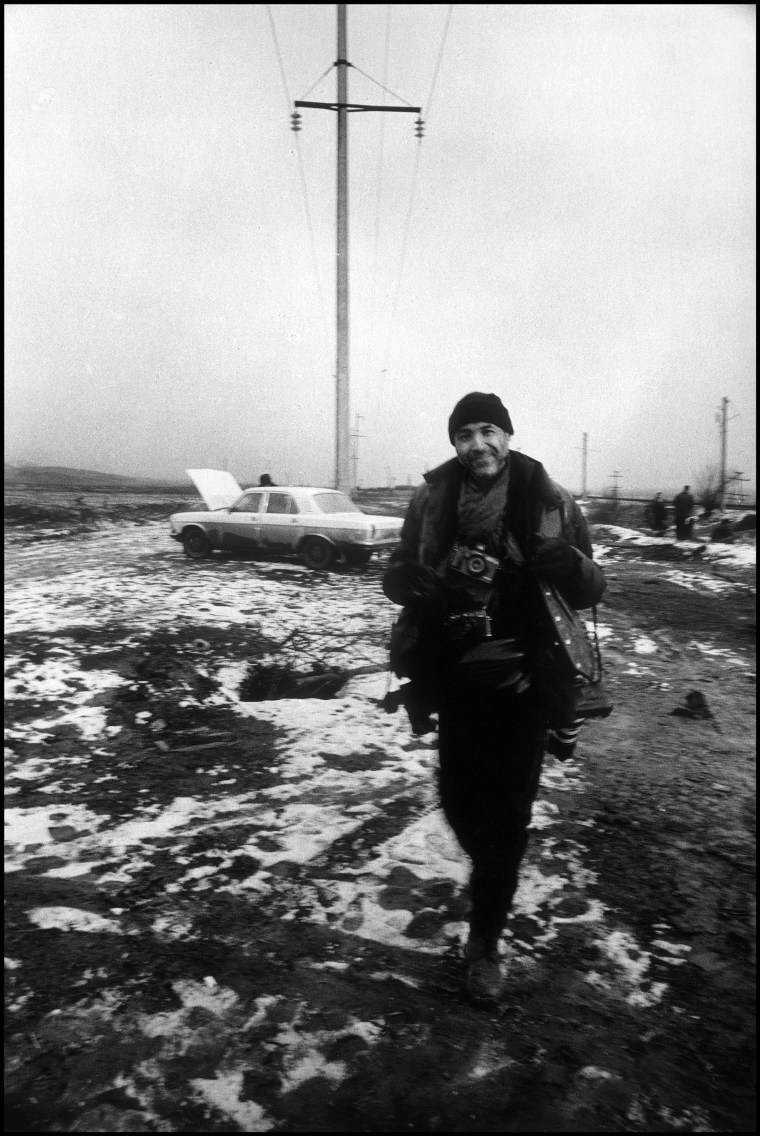

Grozny, January 1995. Stanley Greene—NOOR

Refugees staying in train carriage. Stanley Greene—NOOR

Since the death of her child, Zelina often stares at something far away, elusive. She says she is already dead herself, if only time would hurry up. Grozny, April 2001. Stanley Greene—NOOR

A refugee camp in Ingushetia, June 2000. Stanley Greene—NOOR

In 1986, he moved to Paris, switching to fashion photography during something of a pause in his career. “I was a dilettante, sitting in cafes, taking pictures of girls and doing heroin,” he told Newsweek in 2004. “And [the ghost of] Eugene Smith would show up in this drugged haze, point an accusatory finger at me and say, ‘You must give back.'”

Slowly, he began covering the news, discovering a knack for being in the right place at the right time. He was in East Berlin in 1989 when the wall fell. In 1992, it was Mauritania and Mali, where Tuareg tribesmen “encouraged,” if not forced, him to take pictures of people dying in a refugee camp. The following year, he was in Sudan where he followed the rebel Riek Machar and his second wife, the Englishwoman Emma McCune.

That same year, he was the only Western journalist inside Moscow’s White House (the House of Government building) during a coup attempt against Russian President Boris Yeltsin. “The Russian soldiers were firing constantly,” Greene later wrote. “The only way to get to the other side of the building was to run this gauntlet… The fact that I thought I was gonna die gave me courage. Courage is control of fear… To this day, I really think that this incident is the one that steeled me.”

A rebel leader on the phone in Moscow. Stanley Greene—NOOR

Men look out a window in Moscow. Stanley Greene—NOOR

A Siberian bathhouse in Mariinsk, March 2001. Stanley Greene—NOOR

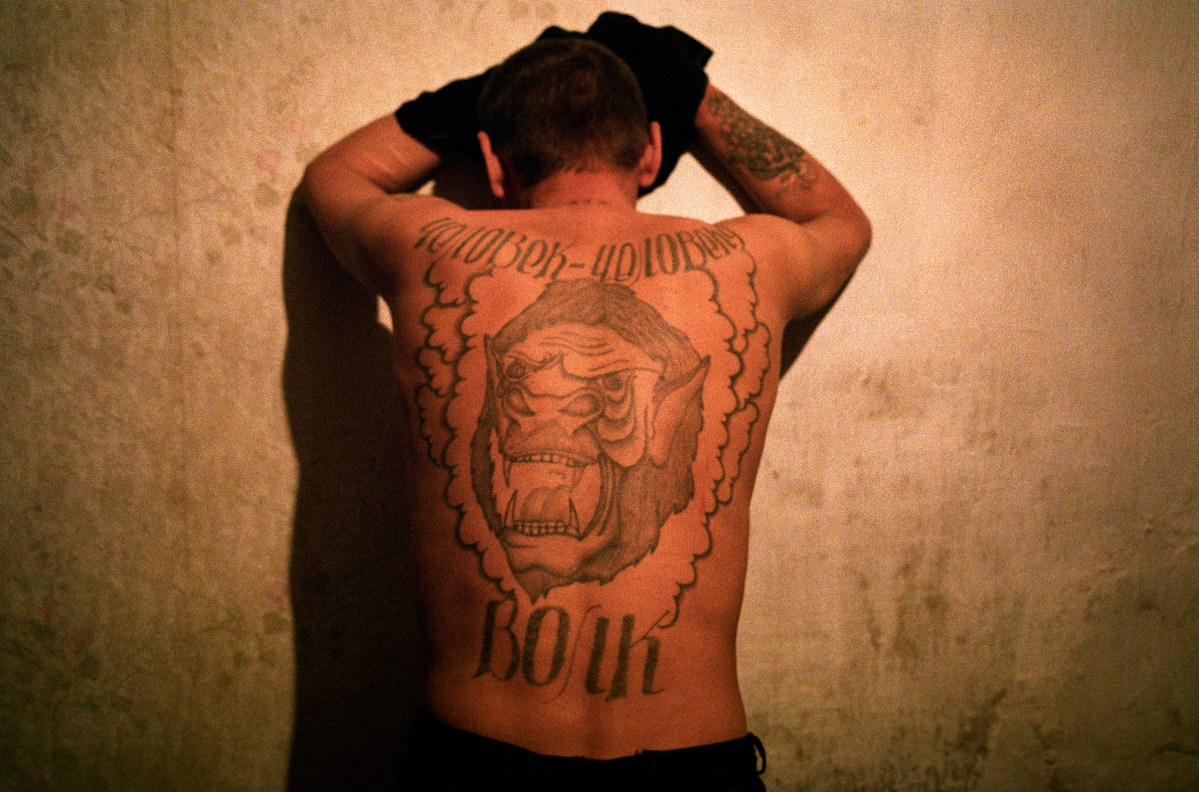

Volydya, or “Wolf,” lives in Rybachi village, close to North Korea, 2002. The tattoo reads “One man is a wolf to another man.” Stanley Greene—NOOR

A Chinese spy who crossed into Russia and was captured, imprisoned and released, in the Ussunysk region, 2002. Russians tattooed his leg so he could not return to China. He became a Russian spy. Stanley Greene—NOOR

After that, Greene started covering conflicts around the world, from the genocide in Rwanda in 1994 to the aftermath of the breakup of the Soviet Union in Azerbaijan and Chechnya, which became an obsession. “Every time a magazine or newspaper offered Chechnya, I would go back,” he wrote in Black Passport. “I’d go to Chechnya in a flash.”

One of these assignments was from The New York Times Magazine in 1996. The story was to follow the traces of Fred Cuny, an American aid worker who had gone missing in Chechnya. “I think the reason I chose [Greene] for that first assignment was because it was going to require a photographer who could bring a huge kind of interior world to his pictures,” says the magazine’s director of photography, Kathy Ryan, “because he’d have to go in search of somebody who was actually missing, he’d have to follow in his footsteps. He was going to have to evoke ghosts.”

For Ryan, Greene was a poetic photojournalist; one who was “photographing things in search of some larger truths about men, war and the tensions in the world,” she tells TIME. “He just sees that kind of metaphorical imagery that transcends just the immediate story.”

A drug raid in Volgograd, Russia, 2001. Stanley Greene—NOOR

Men run after a bombing in Tikrit, Iraq. Stanley Greene—NOOR

The bodies of pro-Russian separatists after an attempt to seize the Donetsk airport, Ukraine, May 2014. Stanley Greene—NOOR

“What Happened to Fred Cuny?” was just one of the many stories Greene filed from Grozny between 1994 and 2003. He produced two books out of the work, including the celebrated Open Wound. It was in Chechnya where he really found his own voice. “He was stunned by the sheer brutality of the Russian assault, deeply identified with the plight of the proud Chechen nation, and realized he could give them a voice with his powerful pictures,” Peter Bouckaert, Human Rights Watch’s Emergencies Director, tells TIME.

But covering war took its toll—on his personal life and the many women he loved along the years, as well as on his psyche. “It was very difficult to go home after covering such events, such conflicts,” Greene told TIME last September. “They say that the soldier develops a 1,000-yard stare. All of a sudden you’re compartmentalizing yourself, your feelings. You don’t know how to express anything anymore. You feel guilty if you have a good time; you feel guilty if you laugh at a joke because you think about all the stuff you’ve been photographing and all of these things that you’ve left behind.”

Mai Mouna Hassan, 10, shot by a drunken Arab militia, rests in the Goz Beida hospital in Chad, January 2007. Stanley Greene—NOOR

A girl looks out a car window, mirroring the horror she’s seen for the last 22 days. Lebanon, July 2006. Stanley Greene—NOOR

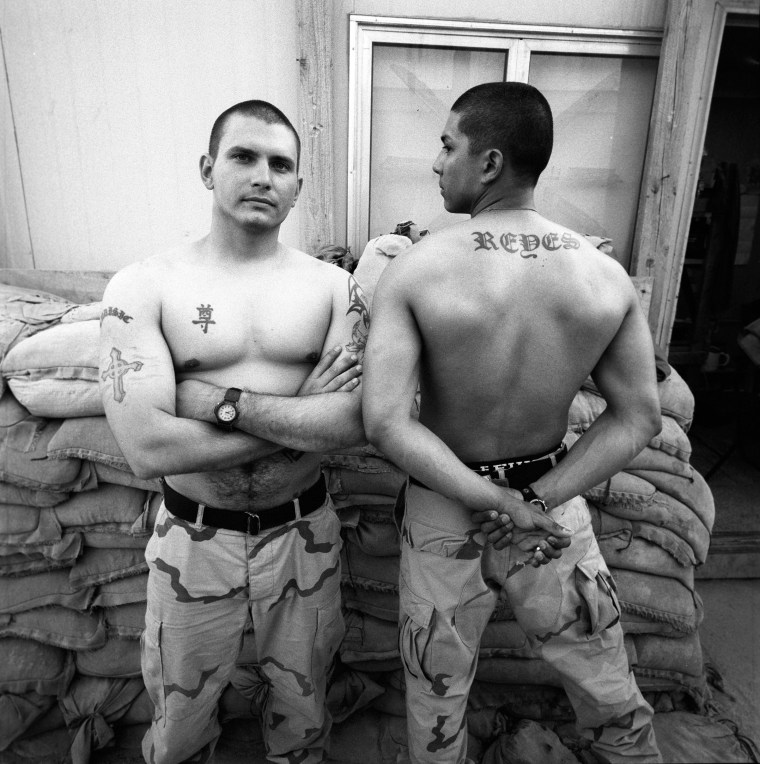

Iraq, June 2005. Stanley Greene—NOOR

Iraq, June 2005. Stanley Greene—NOOR

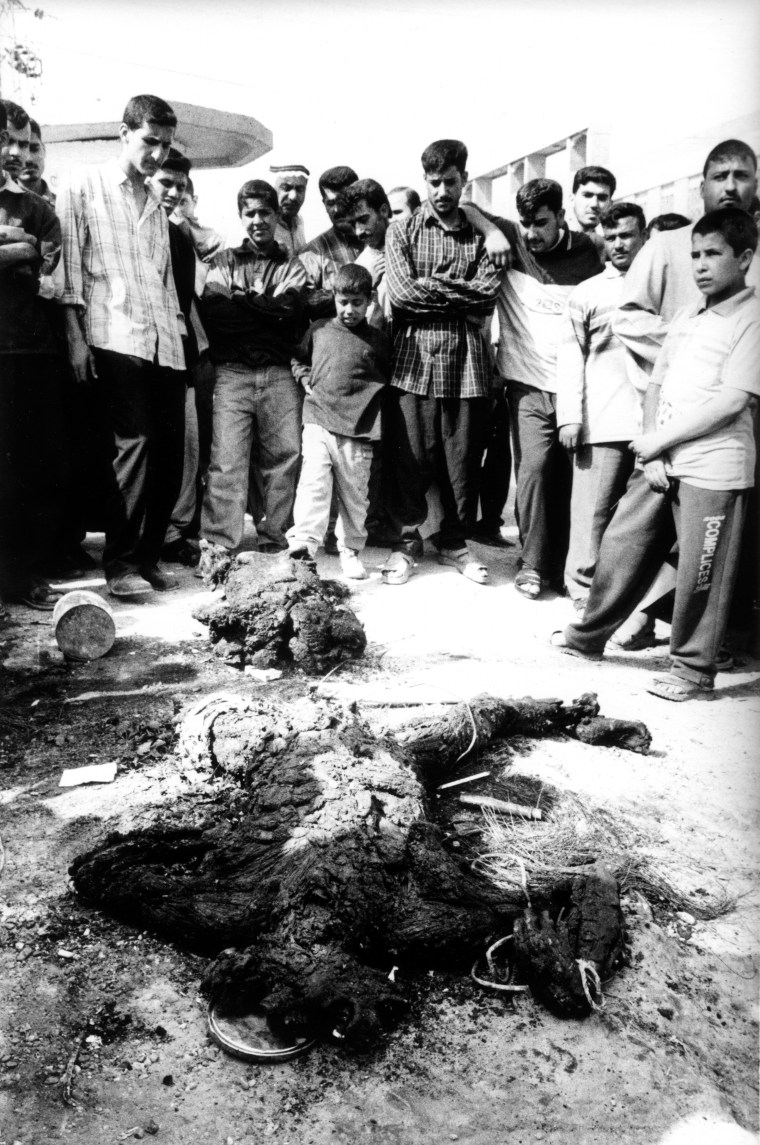

A mob gathers around a mutilated corpse following an attack on two civilian vehicles in Fallujah, March 2004. Stanley Greene—Agence Vu

The old souk in Aleppo, April 2013. Stanley Greene—NOOR

In Black Passport, Greene, quoting Alexey Brodovitch, likened the life of a war photographer to that of a butterfly. “[If] we’re lucky it can last for eight years,” he wrote. “I think you can only keep positive for eight years. If you stay at it longer than that, you turn… I see it in myself, and I see it in all my friends and colleagues. We are all victims of post-traumatic stress and deal with it in different ways. And we’re not beautiful butterflies anymore. We’ve become moths. And what a moth does, it flies into the flame.”

That flame continued to attract him. He was in Iraq in 2004, after the invasion; clasping his Leica M4 in homage to the Vietnam War photographers he hadn’t joined in the 1970s. Again, he was one of the only Western journalists in Fallujah when four Blackwater contractors were killed, their bodies burned and hanged from a bridge.

“It was the most horrendous thing to see,” he told TIME. “Americans that one day must have woken up in the morning and dreamed of love and life and all of the sudden, everything has been taken away from them.”

watch STANLEY GREENE DISCUSS THE two EVENTS THAT CHANGED HIS LIFE

The experience deeply affected Greene. “The people were standing around—they were like at a barbecue,” he said in a video interview [see above]. “A man pulled out a knife, he started to cut away at pieces like souvenirs. And here I am, an American trying to photograph this. And I’d gone to art school, so I’m thinking about the framing and composition. I’m trying to get the right angle because I really want to get the bodies, but also want to get the people because they’re all smiling. All of this is happening and I’m totally dead to it.”

He had lost something that day, he wrote in Black Passport. “[I] knew I was never going to get it back.” And when young photographers approached him with questions on conflict photography, his answer became: “Get a life.” And if they persisted, “[I’d] tell them about the consequences. [I’d] tell them there is no glory. They glamorize the idea of becoming a conflict photographer, but they have no idea what it means.”

But that didn’t stop him from going, from partaking in this “dance with death,” as he told Mike Kamber in the book Photojournalists at War. He was in Lebanon in 2006 during the war. And in Chad and Darfur the following year. In 2008, he went to Afghanistan, and he was in Syria in 2013 when it was already too dangerous for journalists. Along the way, he left his long-time agency, Vu, to launch a new one, NOOR, in 2007 at Visa pour l’Image, with Philip Blenkinsop, Pep Bonet, Kadir van Lohuizen, Francesco Zizola, Jan Grarup, Yuri Kozyrev, Jodi Beiber and Samantha Appleton.

Greene was NOOR’s heart, says van Lohuizen. “I think he really considered NOOR to be his family,” he tells TIME. “He would do anything for NOOR and he kept us sharp. Stanley was my brother. He was my inspiration. I’m losing someone I don’t want to lose.”

But his legacy will live on, through his photographs – eternal testaments of his heart, his integrity and, most of all, his love of life.

Kristel Eerdekens

his life, his legacy

Photographers and editors reflect on Stanley’s impact

Kadir van Lohuizen, photographer, NOOR

I’ll probably realize in a couple of days what I actually lost and what we lost.

Stanley is my brother. He’s my inspiration. We were the first talking about creating NOOR and trying to set our own destiny, to create an agency that was post-analog even though Stanley is very much known for being an analog photographer. He was the heart [of the agency] and I think he really considered NOOR to be his family. He would do anything for NOOR.

He was critical and honest, and that’s sometimes lacking. He was real. We miss that sometimes, with all the contests, the discussions about manipulation, staging. Stanley was real. If there’s one person in the world whom I trust because of his integrity and honesty, it’s Stanley.

I’m losing someone I don’t want to lose.

Kathy Ryan, Director of Photography, The New York Times Magazine

One of the things about Stanley that I’ve always admired hugely was that he was true to himself. His pictures were very much about the world but there was also, always, some kind of personal, profound statement. He is the epitome of the poet photojournalist. He was going out there to document tough and important stories like Chechnya but he was always trying to say something about the emotional undercurrent of the scene he was capturing; because he somehow had the sensitivity to those things. He could arrive in a place and somehow connect on a level that was profound in cultures that were different from his.

You could send him on a job where things wouldn’t be expletively unfolding in front of him and he would figure out a way to evoke the mood and the emotional feel of a place. One such picture is of that woman in Chechnya, capture through a windshield. He somehow singled out this one individual that seemed to sum up the mood of the place at this moment in time. He had that ability. He could literally be in a car driving through this barren landscape and see someone that riveted his attention and make a picture that’s unforgettable.

Stanley’s images are very haunting. After you see them, they stay in your memory. He had that ability as a photographer. His pictures always keep their power over time. Part of it is because he was able to take the particular, specific detail of something – a place, a person, a scene – and make something that’s more universal.

His pictures live and breathe. Nothing in them feels still – everything in them feel like they truly are living, breathing moments captured in those instantaneous seconds. They’re not clinical, they’re not sterile, they’re not pristine. They have a heartbeat. I think that’s where the power of his work came from.

Jon Lee Anderson, author and staff writer, The New Yorker

Amongst the small tribe of international photojournalists who regularly cover war, Stanley Greene was regarded with respect for his frontline work during the savage Chechen War of the Nineties. By the time I met him, during the post 9/11 years, when we both covered the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq, he had become a kind of legendary figure. Not only had he already proved his mettle many times over in different places – memorably documenting history as the Berlin Wall came down, in genocide-ravaged Rwanda, and in the convulsed Russia of the Yeltsin years, Stanley was pretty much the only black man in the business. In addition to Afghanistan and Iraq, I ran across Stanley in Lebanon during the 2006 Israeli war with Hezbollah, in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, and in Libya during the revolt against Muhammar Qaddafi.

Stanley was charismatic, good natured and very cool; a handsome, lanky fellow who always wore a scarf – French-style-bundled around his neck, as well as an earing, John Lennon round sunglasses, and on his head, either a black beret or a bandana, like some kind of rock-and-roll roadie. In most of the places we crossed paths, Stanley was invariably accompanied by Kadir van Lohuizen, a Dutchmen who is a head taller than everyone else in the profession, and who was his devoted sidekick. Eventually, together with several other photojournalists, the two cofounded the NOOR photo agency.

When Stanley and Kadir showed up together to document the messy aftermath of Katrina in the racially-divided city of New Orleans, they quickly discovered that Stanley’s skin color was an issue. During one memorable evening get-together, Stanley — who loved telling a good story – regaled us with accounts of his being stopped and searched at gunpoint by trigger-happy cops. Some of us suggested that as a survival technique, Stanley might try wearing something other than all-black clothes and a black bandana, his chosen attire for the Katrina experience. Stanley heard out such recommendations with a smile, making it abundantly clear he would do no such thing.

Stanley Greene was a brave and good man, and he will be sorely missed.

Philip Blenkinsop, photographer, NOOR

I bid farewell to a golden friend this morning. Stanley was a brave and brilliant artist; this was obvious to anyone familiar with his work, but this was not what made him so rare a human being.

He was driven by the injustices he witnessed; his concerns were for the oppressed who’s company he preferred. He was a champion of the people, sensitive, humble and generous, despite his outward flamboyant appearance.

When he spoke, it was always with the inner confidence of a man who never once had to check his words; something that to the casual observer might have smacked of arrogance; those who knew him, knew better; Stanley had the courage of his convictions; he was of pure intent, someone you could trust, have faith in; someone who would never leave you behind; a man who stood firmly by the things he said.

Stanley had a thing called integrity, the rarest of attributes in today’s world. In all the years I was fortunate to know him and call him a friend, I have nothing but love and respect for the way in which he answered his calling, his rage against intolerance pushing him on when his body was tired. His was the heart of a warrior.

Fly high my gentle friend. I will carry you in my heart always.

MaryAnne Golon, Director of Photography, Washington Post

Tall, poet, follower of light. Painter, war activist, friend, photographer. Proud, handsome, impish, American. Documentarian, provocateur, comedian, storyteller. Parisian, black leather clad from toe to crown, dancer. Giver, taker, slightly unfamiliar yet pronounced accent. Tinted round eyeglasses, mesmerizing voice, curly lashes above sparkling dark eyes, and a long scarf wound carefully around his neck. How could anyone not fall just a little in love with Stanley Greene?

From battlefields in Chechnya and Iraq to the Silk Road in Asia to New Orleans underwater to long defunct punk clubs in San Francisco, Stanley Greene floated through all with his gifted eye and came away with haunting black and white photographs often as unusual as he was. He believed always in film and hated digital photography. His photographs were sometimes blurry yet always soulful. His books, including Black Passport and Open Wound, will live permanently in photography’s history and will remain as fresh and important in my memory as Stanley will forever be.

Peter Bouckaert, Emergencies Director, Human Rights Watch

He was a great photographer and an even greater human being. We lived through a lot together in Chechnya, seeing the destruction of a people we loved, and during the war in Lebanon.

He would crack me up because in every war we worked together he would call me and say, full of outrage, “Peter, it is a genocide! You have to stop it!” slightly overestimating my influence over events. He was one of the most sensitive people I know, and he was often devastated by what he witnessed.

Stanley, you lived a truly unique life, and never chose the easy path. You were a dearly beloved friend, and a photographer of immense passion and talent. I will forever cherish the steps we took alongside each other. You will be missed dear Stanley.

Christopher Anderson, photographer, Magnum Photos

When I think about Stanley, more than any single image, I think about the heart that he put into his pictures.

For someone who has seen the things that Stanley saw, he never seemed jaded by it. He always seemed to still have this wide-eyed, heartfelt, almost naïve – and I don’t use that in a negative sense – almost childlike sense of wonder at the world.

There’s always these controversies going on in photojournalism – but it’s not about Photoshop, it’s about the lack of heart. If there’s one thing that Stanley Greene had, that hopefully could be an example to the documentary photo world, was his heart. What you saw in his pictures was about having something to say and about him pouring his heart into it.

In a cold, cynical world, in an industry that can seemingly be motivated by fame and glory and capturing the big prize, Stanley Greene was motivated by his heart. That was the machine that drove him.

The rings and the leathers will just make the movie better.

James Wellford, Senior Photo Editor, National Geographic

The forever-phenomenal Stanley. He had a vengeance for the truth, dignity and justice in the world. He was always a complicated character whether it was in love, whether it was in living situations. He sustained a lot longer than people in their right mind sustained. It goes back to his genuine joy and integrity and interest. He was always remarkably innocent.

One of the great American photographers is setting sail.

Teun van der Heijden, designer

I was always very intrigued by how Stanley presented himself, often larger than life. During the four years that we worked on Black Passport I did not only get to know him as a demanding, passionate activist but mostly as a kind and gentle friend. I will never forget the philosophical conversations we had, that sometimes took a full day, in which we reflected on each others lives.

Lars Boering, Managing Director, World Press Photo

I’m very sad to hear that Stanley Greene has passed away–a legend of photojournalism who’ll be missed for both his iconic work and charisma. Stanley was one of a kind and a great example to many photographers. We will miss his sharp and original voice a lot.

David Guttenfelder, photographer

I looked to Stanley’s books Open Wound and Black Passport to see what raw, masterpiece photography looks like. I watched Stanley himself to see what a raw, monumental life looks like.

Alice Gabriner, International Photo Editor, TIME

I remember vividly seeing Stanley’s pictures for the first time back in the early 1990s. Somehow he’d managed to get inside the Russian White House while it was under siege. More than just unique in access, what was revealed, and is true of the entirety of his photographic legacy, is a visual voice like no other—intimate, unconventional, free yet complex, passionate, moody, romantic and completely engaging. In fact, that’s pretty much the way I would describe Stanley.

Last year at Visa pour l’Image, we reminisced about the festival and its formative impact. Intertwined with memories around photography, for Stanley, Perpignan was where his family/agency/tribe, NOOR, was born and cherished love affairs began.

Disarmingly open, he also talked about how sick he was, which surprised me when one night he took the lead in guiding a group to the screening. After crisscrossing on back streets, we realized he had no idea where he was going. Some of us were huffing and puffing trying to keep up, while Stanley walked briskly way ahead of the pack.

Robert Stevens, former international photo editor, TIME

Stanley was always incredibly focused on his assignments and only took the ones he was passionate about. If he did not feel strongly about the subject he would turn down work. This made it harder for him to make a living but he never wavered from this. These are the most important thing I remember about him: absolute belief, passion and obsessive determination to get the best images possible.

Yuri Kozyrev, photographer, NOOR

I deeply admired Stanley. His understanding of the world and life. I loved being next to him and to listen to his thoughts. He was a true poet. We knew he was sick for a long time but he still always found the strength to travel, the time to be with friends, the energy to talk about work with his colleagues at the agency – which for him was like a family.

I hoped for a miracle, and told myself that this time too, like many others before, Stanley would pull through because he was a fighter and a survivor.

Yesterday, he was surrounded by close friends from Noor and beyond. We were his family. Old friends from Russia in the 90¹s were there, people I hadn’t seen in years. It was terribly sad and emotional and yet beautiful to see that some many people had made the trip to bid him farewell one last time. He was truly loved and deeply respected.

We first met in Chechya. He heard I was there, and wanted to meet. He looked through my pictures, and helped a lot. He was generous, a cool looking guy with silver rings who filled any room he entered with his big personality and sensitive soul.

We shared Chechya, Iraq, Afghanistan and much more. In Black Passport, a cult book for any self respecting photographer, he was so raw and honest about his life. We know his pictures, but this was a unique work of painful self reflection that showed his pain, demons and deep humanity. It took guts and only a brave soul like him could have pulled it off. But that’s Stanley. He was the Capa of my generation.

Jerome Delay, Africa chief photographer, Associated Press

Stanley spent his life documenting the strife of humanity, denouncing the horrors from Darfur to Chechnya and Iraq. His passion for photography and people was second to none. When not in the field, Stanley would spend hours sharing his passion with colleagues and students alike, wearing his trademark leather jacket, skull rings and round spectacles.

We have just lost one of the pillars of modern photography, an eyewitness, a confidant, an exceptional human being.

Thomas Dworzak—Magnum Photos

Alice Gabriner, who edited this photo essay, is TIME’s International Photo Editor.

Olivier Laurent is the editor of TIME LightBox. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram @olivierclaurent