Haitian migrants follow a coyote, left, toward their encampment on Dec. 8 in Capurganá, Colombia, the gateway to North America.

Haitian migrants follow a coyote, left, toward their encampment on Dec. 8 in Capurganá, Colombia, the gateway to North America.

Smugglers Inc.

A voyage through the fraught, life-changing and totally routine $35 billion human-smuggling business

Updated Friday, Feb. 16

They arrive as boxes. Doña Katia’s contact in Colombia calls to say, “I’ve got six boxes coming to you next Tuesday,” and she understands his meaning. In the business of moving people illegally across international borders, discretion is required.

Still cajas, or boxes, sounds a little cold to Katia, who prefers to talk up the human element of human smuggling. So the Indians and Eritreans, the Bangladeshis and Haitians she collects on the border where Panama meets Costa Rica acquire a new name when they travel across the latter country in her car, then board a boat to Nicaragua and a bus to Honduras, hurdling the series of borders toward the U.S. “I call them pollitos,” she says. Baby chickens.

In Paso Canoas, a shabby Costa Rican border town facing Panama, at least 14 other smugglers—sometimes called coyotes—compete for the migrant trade. Katia, a mother of two, calculates that she has sneaked between 500 and 600 people through the heart of Central America in the past 2½ years. She knows her customers not by their names but by their faces, which show up on her phone in texts sent from another smuggler preparing to hand them off: brown men, and a few women, in sheepish clusters outside the Western Union where they have retrieved cash from a relative to cover the next leg. From South Asia, the journey costs anywhere from $10,000 to three times as much.

Around the world, borders appear to be making a comeback. Donald Trump was elected to the U.S. presidency promising a wall. Britain recoiled from the European Union and the foreigners they were forced to allow in. But below the surface, things are still moving. The forces that compel people to move on from what Trump calls “sh-thole countries”—higher wages somewhere else; the chance to be the one sending money home, rather than the one receiving it—have lost none of their tidal power. In 2015, every 30th person on earth was living in a country where they weren’t born, or on the way to one. That’s nearly a quarter of a billion people.

Katia began smuggling migrants—she calls them her “baby chickens”—toward the U.S. two and a half years ago.

Katia began smuggling migrants—she calls them her “baby chickens”—toward the U.S. two and a half years ago.

They chose to go. The vast majority of humans in migration are not trafficked. (The U.S. State Department’s top estimate of people being moved against their will is 800,000.) Most are not fleeing war. More than 9 out of 10 people stealing across international borders—93%, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM)—scrimped and borrowed to uproot themselves. The IOM says smugglers collect $35 billion a year to facilitate what is simultaneously an epic journey, a crime and a service.

At base, it’s a business. And Katia, as she sometimes calls herself, offers a rare view into how it works. In a series of interviews with TIME, she laid out her smuggling operation in detail, from the bribe expected at a police checkpoint in Nicaragua to the surprisingly modest monthly profit she pockets from work that outsiders assume is part of a vastly lucrative industry dominated by hardened criminal gangs.

“I think, fundamentally, this is a process of global osmosis,” says Tuesday Reitano, whose title is the deputy director at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime but who regards the phenomenon as more natural than iniquitous. “People are moving around through semipermeable borders. They go from where it’s poor to where it’s rich until they overwhelm the system and make that less rich, and then they go somewhere else. And ultimately, it all ends up at room temperature.”

That the U.S. is overwhelmed and growing less rich because of immigrants was a premise that helped lift Trump into office. That premise may not hold up to scrutiny; the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development suggests that migrants contribute more in taxes than they consume in benefits. But emotions matter in politics, and working-class wages in the U.S. have been stagnant or worse since companies became freer to move operations to countries where labor costs less, a central tenet of globalization. The other half of that equation is that labor will ignore borders as well.

The largest number of migrants, according to the IOM, set off from India. And the world’s top destination remains the U.S. So there was a logic to finding, on an overcast December afternoon in Costa Rica, a tall, brown-eyed man from Punjab standing beside the Christmas tree in Katia’s living room.

The journey of Mulkit Kumar began a month earlier, in a northeastern India village that’s small but hardly disconnected. To see his wife holding their baby in the house he left, the construction worker presses the video icon on his smartphone. When he decided to leave that house for good, he used that same phone to dial a number in New Delhi. “Friend of a friend,” Kumar says of how he found the first smuggler. “There are a lot of people who have made the journey before.”

We are all in Katia’s house, a modest bungalow built with her earnings as a coyote, alive with her niece’s chatter and her son’s PlayStation, when her own phone rings. She yelps. It’s the Delhi contact. “I already withdrew the money,” she tells him. “My love,” he coos in reply, in Hindi-accented Spanish.

“Yes, I’m a good person,” she says. “Friday I will get the guy out, and then the following week I’ll get the other guys who are coming from Ecuador.”

Between them, the two smugglers arranged most of Kumar’s journey, which will be financed—as most migrant travel is—by the traveler’s extended family. Relocating a wage earner to a country with much higher wages and the prospect of upward mobility amounts to an investment, and a sound one. The transplant will wire home a few hundred dollars a month, likely for decades. Worldwide, such remittances were on track to total $444 billion in 2017, according to the World Bank. That total has nearly quintupled over the past 15 years, the bank says, and proved a far more stable source of funds for poor countries than either foreign direct investment or private investment capital.

Pakistani and Indian migrants arrive at Capurganá on a smuggler’s boat from Turbo, Colombia, on Dec. 8.

Pakistani and Indian migrants arrive at Capurganá on a smuggler’s boat from Turbo, Colombia, on Dec. 8.

Kumar says his four sisters came together to cover his expenses: 140 rupees ($2) for the bus ride to Delhi and 60,000 rupees (about $950) for the airfare to Quito, the capital of Ecuador. Smugglers say that if you want to go to the U.S., start by booking a ticket to Quito. Ten years ago, the South American nation threw open its doors to the world, requiring no visitor to arrive with as a visa. And though the policy has tightened some since, the reputation endures. The border of Colombia lies just 150 miles away, and from there it’s a couple days up the Central America trail to the edge of North America.

The journey is life-changing, fraught—and routine. Five years ago, only a few hundred migrants routed themselves to the U.S. through South America, but the number soared in 2015 to nearly 30,000, according to Colombia’s government, which took measures to regularize the journey. In the grubby port city of Turbo, officials last year began taking the names of migrants as they boarded ferries that were headed north. A ferryman’s clipboard shows that 46 migrants made the trip one day in October, 106 the next. Each carried a salvo conducto, or “safe conduct” pass, permitting them to remain in the country for five days.

The trip from Turbo in a long, open boat crosses the Gulf of Urabá and ends in another realm. The remote town of Capurganá lies just inside Colombia but beyond the writ of its government. The area—rebel territory during the nation’s long civil war—is now controlled by a mafia, the Gulf Clan, which reliably services two sets of transient populations. Tourists come for the picturesque beach, and migrants to stage for the arduous hike into Panama. On holiday weekends, they compete for hotel rooms.

“There were so many of them, they used to put different-colored bracelets on them,” says local resident Wilberto Peñaloza, referring to the migrants, not the tourists. Smuggling is a volume business here. Coyotes coordinate to keep their “lines” moving smoothly and last year organized to cut a fresh trail north a safe distance from the route used to traffic narcotics.

Both trails run through the Darién Gap, the forbidding, roadless jungle that separates Central America from South. Walking it takes as long as a week on mud trails over steep hills and across meandering rivers. Hazards include snakes, thieves and being returned by Panama to Capurganá, where the hopeful wait for wire transfers to try again. One piece of graffiti calls the place “purgatory.” “Seeing all the migrants, you see all the money,” says a former smuggler in Capurganá known as the Horse. He built a house on the profits from the $40 to $70 he charged for a day’s start into the jungle. Most of his clients were Haitians. “They have an American dream,” he says. “It’s like a headache they get that won’t go away until they get what they’re looking for.”

The road at the end of town in Capurganá, where migrants would pass through at night to enter the jungle before local coyotes changed the route to avoid authorities, on Oct. 3, 2017.

The road at the end of town in Capurganá, where migrants would pass through at night to enter the jungle before local coyotes changed the route to avoid authorities, on Oct. 3, 2017.

Capurganá exists, like “irregular migration” itself, in the twilight between laws as written and reality as lived. Consider Yikalo Gebrekristos, who TIME finds idling outside a Catholic church a block inland. His journey began in Khartoum, the Sudanese capital, which teems with foreigners fleeing other countries in Africa’s Horn, including his own nation of Eritrea. The Khartoum police shake down migrants daily. But Gebrekristos opted to put his money into the kind of corruption that would work for him, climbing into one of the late-model cars that double as offices for underground travel agents. There he learned the price for a Sudanese passport—$3,000—then that of a ticket to Quito. The $15,000 he had spent when we found him came from relatives, to whom he owed not only cash but possibly his life. “If you have a good family, you go to America,” Gebrekristos explains. “If you don’t have a good family, you go by Mediterranean Sea”—the route to Europe, which runs through Libya, where African migrants are routinely enslaved or abused for months, if not years, before getting a place on a dangerous boat.

But traveling through the Americas is no snap. Near a poster bidding tourists Dare the Darién, an Ecuadoran migrant recounted attempting the journey four times with no success, paying $300, $200, $150 and $200, only to be sent back. He was about to try yet another coyote. “When the things are legal, you can look into the details,” he explains. “But when it’s illegal, it’s a risk you have to take.”

Things are getting tougher. At midday on Dec. 11, TIME found a Bangladeshi man named Kamal Hussein in an abandoned resort, chipping at a coconut with a flimsy knife for a meal. Three weeks earlier he had emerged from the Darién in Panama after losing his money and phone to bandits.

But instead of allowing Hussein to continue north, as they might have done a year ago, Panamanian officials detained him for 14 days, then sent him back to Colombia. These days, the country is overwhelmed by the flow of northbound migrants. “We were receiving 300 or 500 a day,” Javier Rudas of the Panama Migration Service tells TIME. He notes that Panama’s agreement with Costa Rica allowed it to send only 100 north per day. “So we had a big balloon that kept filling.” The cost of maintaining camps to hold the excess thousands was more than what the government wanted to bear. For that reason, many are turned back to Capurganá, to try again.

“At the end of the day, they’re understanding it,” Rudas says, “and they’re looking for new routes. At the end of the day, they get to the United States.”

In Turbo, Colombia, locals turn out for the funeral procession for truck driver Marco Antonio Builes, the victim of an armed robbery, on Oct. 1, 2017.

In Turbo, Colombia, locals turn out for the funeral procession for truck driver Marco Antonio Builes, the victim of an armed robbery, on Oct. 1, 2017.

Sure enough, in Costa Rica, Katia keeps doing business. It’s not like a year or two ago, when she might have seen as many as 35 migrants a day. Those were flush times: the U.S. had given temporary protected status to Haitians because of the 2010 earthquake, and took a softer line on Cubans because of Castro. The door closed when the Obama Administration changed the Cuba policy, but the route remains popular, mostly with South Asians. Of the 235 detainees in the Panamanian camp where Hussein was briefly held, 185 were from India.

“You try to do excellent work and lower your prices so you can keep business going,” Katia says in her bungalow. She snagged the Delhi contact by undercutting his previous Central American smuggler, who charged $2,700 per migrant. “I’ll give you better rates,” Katia said, offering $2,300.

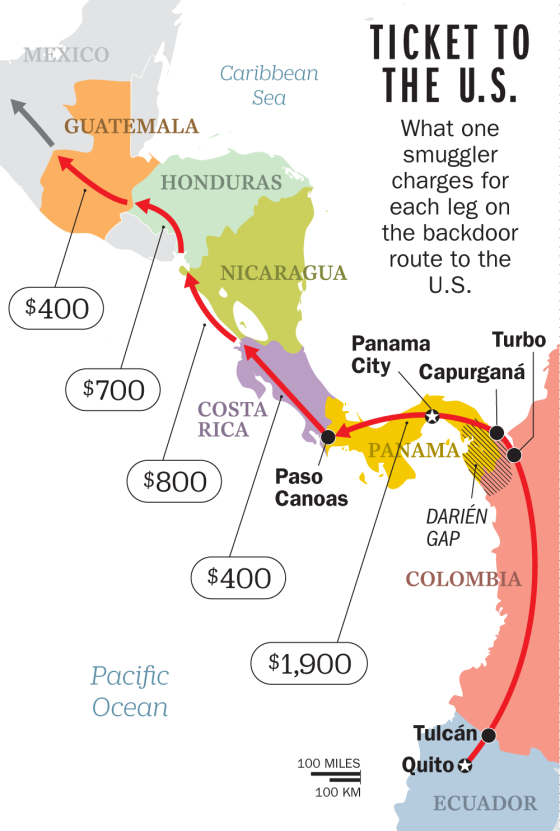

“He gets them from India to Ecuador, and I get them from Ecuador to Mexico,” she says, and launches into a description of her enterprise. From Quito, migrants go by bus to Tulcán, the city in Ecuador nearest to the Colombia border. There her contact meets them, and arranges transport north to Capurganá. When they emerge from the Darién, they travel by taxi to Panama City, then are directed to a bus. “There’s a compartment in the bus where they hide,” Katia says, “and the bus brings them here.”

The Paso Canoas border area is known for shopping. Locals from Costa Rica and Panama come to buy hard-to-find items. Here, mannequins at a women’s clothing store on Dec. 21, 2017.

The Paso Canoas border area is known for shopping. Locals from Costa Rica and Panama come to buy hard-to-find items. Here, mannequins at a women’s clothing store on Dec. 21, 2017.

“Here” is the strikingly informal boundary where Panama meets Costa Rica. (In some places, it’s simply a median between parallel highways.) Still, she arranges crossings into waiting taxis at 3 a.m. and posts a lookout, because what she’s doing is illegal, though she has a hard time regarding it as immoral. “If I was making them do something they didn’t want to do, that’d be different,” Katia says. “But I’m just helping them get to liberty, which for them is the United States.”

The taxis bring them to the spare room at her house or to cheap hotels nearby. After the deprivations of the Darién, she can arrange a haircut, new clothes and a phone for an additional $200. If anyone shows up without cash, her attitude changes abruptly. “You don’t have the money?” she snaps, when a Cuban arrives empty-handed.

Prices have risen with the uncertainty on both sides of the Darién Gap. The passage from Colombia to Costa Rica now costs $1,900, Katia says. From Costa Rica north to Mexico, it’s another $2,300. She says her profit on each migrant works out to just $120, all of which comes out of the $400 she charges for the Costa Rica leg. The price for the next rungs on the ladder—$800 for Nicaragua, $700 for Honduras—are consumed by the cost of drivers, food, shelter and bribes.

“I can’t charge them more, because they’re already crying about the price,” she says, “and if I charge $100 more per country…” Left unsaid: Someone will undercut her. “I can’t,” she says with a shrug.

The bribes add up. Police staff permanent checkpoints in each country, and at the first one in Costa Rica, the charge is $35 per migrant, paid to the officer whom Katia approached through a family member. Travel is timed for his shifts and is highly choreographed: she photographs the license plate of a semitrailer, then texts it to the officer, who orders the truck to stop. While it blocks the view of his colleagues, the car of migrants slips past.

Near the border with Nicaragua to the north, the car detours to the coast, and the migrants then file to a boat that’s waiting for dark. It’s a three-hour voyage, and Katia says she does not sleep until she gets a call confirming the landing in Nicaragua and transfer to a bus. “Two checkpoints in Nicaragua,” she says matter-of-factly. “Forty dollars a person.” As they approach Honduras, the migrants set off on foot for six hours to cross the border through the jungle. If they encounter bandits, it’s another $40 per head to keep moving.

“Honduras is easier,” Katia says. “Once they’re in Honduras, I relax, because I’ve been working with the same guy there for 2½ years.” The country still offers salvo conductos, but getting one can involve spending a week or two in detention, so many migrants pay the coyotes to simply take them to the next country to the north, Guatemala. “The local indigenous people will work with them,” she says. “The coyote will write down the license-plate number, send photos of them to the indigenous person who will be along the way, get them off the bus, and put them on the next.”

Same for the cop at the checkpoint. “The coyote goes ahead, pays them off and shows them the pictures of the migrants, so when the cop gets on the bus and sees the people from the photo, he just lets them go,” Katia says. They enter Guatemala by horseback and proceed toward Mexico’s porous southern border. There, those who want to apply for asylum present themselves to the authorities; others find yet another coyote to attempt the U.S. border.

“I’m responsible,” Katia insists, a little proudly. “If something happens, they get robbed, left behind, I’m the one that responds. Other coyotes don’t care, they’ll just take the money and leave them, robbed or whatever.” She flips through her digital scrapbook to find a woman who arrived in tears. “She had been raped, and had an infection.” A trip to the hospital was arranged. “And this blond woman says she was raped also,” Katia says, a few clicks on. “The coyote in the jungle separated her from the group and told her she couldn’t move forward until she slept with him.”

Such stories are not rare. But researchers say brutalizing the customer does not work as a business model, especially in the age of social media. Katia, like her contact in Delhi, isn’t even a full-time smuggler; each has a day job in transport. That’s both logical and the norm, Reitano of the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime writes, with co-author Peter Tinti, in Migrant, Refugee, Smuggler, Savior. People with routine, intimate knowledge of the mechanics of international travel are best positioned to detect and exploit its gaps.

But heartless scammers keep the popular image alive by swooping into high-profile events, like the 2014 Syrian refugee rush to the Aegean Sea. Reitano says such surges attract opportunists who take migrants’ money and then abscond, as well as organized-crime networks chasing a quick payoff. Most smugglers, however, are in it for the long haul. “The whole system is generally not about getting one payment,” says Reitano. “It’s about getting payments through the years. Nobody wants it to fail … except the receiving states.”

Katia’s monthly income from smuggling averages $800—the same as from her day job, she says. “They make what everybody else makes,” says Gabriella E. Sanchez, a research fellow at the Migration Policy

Centre at the European University Institute. “People don’t want to hear that. This notion of organized crime has never been further than the reality of the facilitation we see around the world.”

Illusions die hard, though. In her living room, Katia beams while recalling an email from a onetime customer thanking her for helping him get to the U.S., where he opened a pizza parlor. “I feel good, feeling that it hasn��t all been about money,” she says. But that extra $800 a month let her move into a house she built; it paid for the video console her son toggles from across the room and family trips to a water park. It also explains why she got up in the night to gather the 18 Africans whom her mendacious new drivers had dropped by the side of the road, a five hours’ drive from the border with Nicaragua. Collecting them was the right thing to do, but she also needed the reference.

“Yes,” she says. “They recommend me to their friend!”

A satisfied smile. “Business.”

A horse grazes in a palm field, near the border area where Katia works, on Dec. 20, 2017.

A horse grazes in a palm field, near the border area where Katia works, on Dec. 20, 2017.

Poole’s reporting was supported by a grant from the International Women’s Media Foundation

Correction: The original version of this story incorrectly identified Gabriella E. Sanchez. She is a research fellow at the Migration Policy Centre at the European University Institute. She is no longer a professor at the University of Texas at El Paso.