More than 70 years later, the prosecution of a 94-year-old former SS guard renews questions about how to assign blame for the Holocaust

On a cold, gray morning in February, Irene Weiss was waiting patiently in the courtroom in Detmold, a small city in northern Germany. She had come a long way from her home in Virginia to testify in the trial of Reinhold Hanning, a former Nazi SS guard. The trial was off to a late start because Hanning, 94, was waiting for a wheelchair to take him into court. Because of Hanning’s health and age, the trial was restricted to only two hours of court time, two days per week. Every delay meant the 85-year-old Weiss might have to stay in Germany longer than she had planned. And she had already been waiting for this moment a very long time.

Finally, Hanning was wheeled through the entrance in a jacket, glasses and a canary yellow sweater, his chin pressed down into his chest to avoid looking into the cameras wielded by dozens of journalists in the courtroom. It was difficult to imagine that the frail old man had once been a young guard at Auschwitz. Hanning had been charged with being an accessory to murder in the deaths of 170,000 people killed at the death camp while he served there from January 1943 to June 1944. Weiss, who was a 13-year-old Jewish prisoner at Auschwitz during that period, and whose family was killed at the camp, was one of several witnesses testifying in the case brought by a city prosecutor in northern Germany.

Weiss doesn’t remember Hanning personally. None of the camp survivors who have testified at the trial do. But to the court at Detmold, that didn’t matter. They were there to paint a picture of what it was like in Auschwitz, and what role Hanning would have played as one of the thousands of SS personnel who served there. Thanks to a new legal strategy meant to hold even low-ranking ex-Nazis broadly responsible for the Holocaust, it’s become easier to prosecute cases against aging defendants—even without evidence of what specific acts individuals like Hanning may have committed more than 70 years ago.

Not everyone is comfortable with the idea of prosecuting the very elderly. But some experts believe these trials have a moral purpose that goes beyond black-and-white legal responsibility. “The optics are not brilliant, obviously,” says Lawrence Douglas, a legal scholar at Amherst College who has studied Nazi crimes. But these new trials are considered symbolically important, a way to show that a German legal system that struggled for decades to hold ex-Nazis accountable can finally bring them to justice.” As Douglas puts it, “It is better late than never.”

After the Allies tried top-ranking members of the Third Reich in a series of 13 military tribunals at Nuremberg from 1945 to 1949, a newly partitioned Germany took over prosecution of the remaining Nazi criminals. While communist East Germany’s trials were highly ideological—politics often trumped justice—democratic West Germany struggled as well. Allied attempts at “denazification” had largely failed—as of 1945, historians estimate that as many as 8 million people, about 10% of the total German population, were former members of the Nazi party, which meant the judiciary was filled with judges with Nazi connections. Rather than use a 1954 law specifically tailored to genocide, the West German justice system decided to pursue these crimes under the German penal code, effectively treating deaths in the Holocaust like any other murder. That meant prosecutors had to prove that defendants were personally guilty of killings—a high bar because of the bureaucracy of the death camps. “That was probably a cardinal mistake,” says historian Edith Raim, an expert on West German prosecutions of Nazis.

The German government did keep investigating crimes through a central office established in 1958 in Ludwigsburg in southwest Germany. Their work led to the most infamous series of Nazi prosecutions: trials in Frankfurt from 1963 to 1965 of 22 second- and third-tier Auschwitz personnel. Many defendants argued successfully that they had only been following orders, so that even soldiers who had shot and killed prisoners could be convicted only on lesser charges. In the end, only the worst sadists were convicted of murder. Of the 17 found guilty of a charge, just six were sentenced to life in prison, while the others received sentences ranging from three to 14 years.

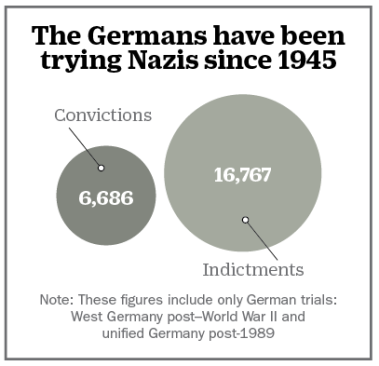

Little changed in the years that followed. While perhaps 1,000 camp personnel faced trials in other countries, a now-united Germany has convicted fewer than 50 of the estimated 6,000 to 7,000 SS who served at Auschwitz and survived the war, according to German historian Andreas Eichmüller. So in the early 2000s, in an effort to increase the conviction rate, prosecutors at Ludwigsburg turned to a strategy suggested in the 1960s by Fritz Bauer, the attorney general of the German state of Hesse, who had been involved in the Frankfurt trials. Bauer, who had himself been imprisoned as a Jew in a concentration camp, argued that anyone who served in Auschwitz should be held responsible because they had been part of a killing machine.

The strategy succeeded for the first time in 2011 with the conviction of John Demjanjuk, a Ukrainian guard at the Sobibor death camp. “With the Demjanjuk case, they finally created a prosecutorial approach that got the logic of genocide down: if you were working in a factory of death, that made you an accessory to murder because your job was to facilitate the killing of human beings,” says Douglas, the Amherst historian. “That’s an incredible legal breakthrough.”

After Demjanjuk, the Ludwigsburg investigators broadened their search for Nazis who had served at any of the six death camps or with the Einsatzgruppen, a special force assigned to mass killing. The first trial to come out of their work was the case of a bookkeeper at Auschwitz, Oskar Groening, who was convicted in 2015 in a court in Lueneburg of being an accessory to the murder of 300,000 people. Three other trials were scheduled for 2016, including Hanning’s, but one defendant has already died and the case of Hubert Zafke, a medic at Auschwitz, was suspended in February when a doctor found him unfit to stand trial. As of March, 13 more cases were in different phases of investigation, according to Jens Rommel, head of the central office for investigating Nazi crimes in Ludwigsburg.

But the new legal framework has its own complications. Demjanjuk appealed his case and died while awaiting the appeal, so the conviction is not considered legally binding. Groening has appealed his case to the German Federal Court of Justice, which could offer a decision soon. Rommel hopes the court will clarify what the prosecutors have to prove: “Do we need a concrete action, like selecting [a person to go to the gas chamber]?” he asks. “Or is it enough just to have been a guard at Auschwitz and to have known what happened there?”

With a trial focused on the broader context of the camp rather than the actions of the defendant himself, Hanning has often seemed like a void at the center of his own murder case. From the indictment, archival materials and a written statement read by his lawyers in court, a sparse picture of Hanning’s life has emerged. He was born on Dec. 28, 1921, and left school at 14 to work in a factory. Hanning joined the Hitler youth in 1935 and the Waffen SS, the armed wing of the SS, in 1940, at his stepmother’s suggestion. He fought in major battles before he was wounded by grenade splinters in Kiev in September 1941. Because of his wounds, his commander determined he was not fit for combat duty, and he was promoted and sent to Auschwitz in 1942. He was initially assigned to register work details, away from the killing, but he later took a post in the guard tower.

According to the indictment, guards in Hanning’s company had to monitor arriving prisoners as they were chosen to work or be sent to their deaths in the gas chambers. It was a process referred to by survivors and witnesses as “selection.” In his statement in court, Hanning did not describe witnessing selections or any personal involvement in killing. But he did admit to knowing about it. “Nobody talked to us about it in the first days there, but if someone, like me, was there for a long time, then one learned what was going on,” his lawyer read from a statement from Hanning. “People were shot, gassed and burned. I could see how corpses were taken back and forth or moved out. I could smell the burning bodies.”

According to the testimony Irene Weiss gave in the trial in February, she was 13 when she was sent to Auschwitz with her family in May 1944. Weiss remembers that when they arrived, tired and disoriented, a guard used a stick to direct prisoners where to go. Her mother and young siblings were sent in one direction—where she assumes they were immediately killed—while her father and older brother were sent to work, before they eventually died. When the guard came to Weiss, he hesitated before sending her with her older sister to labor. It was a lifesaving decision—normally Weiss would have been sent to the gas chambers with those under 14—but she believes that the coat and kerchief she was wearing made her look older.

Like the other witnesses, Weiss doesn’t remember Hanning from her time at Auschwitz. That is a point Hanning’s lawyers have tried to use in the trial to show how insignificant he was. “There were the Nuremberg trials after the war, where the big shots and responsible officers were tried and often sentenced to death,” Hanning’s attorney Andreas Scharmer told TIME. “And the further you go down the chain of command, the more the question arises of how far the legal responsibility goes.” A ruling in the Hanning case is expected this summer.

Rebecca Wittmann, a historian at the University of Toronto, believes the trials are flawed because the German courts should not be using the ordinary criminal code to prosecute the Holocaust, regardless of how they interpret the law. Raim, the German expert on postwar Nazi trials, agrees, arguing that while German courts should have implemented and used a law specifically to address genocide years ago, that failure doesn’t justify a tardy and clumsy legal solution now. “The German courts didn’t get their act together for the last 70 years,” she says. “It is not the fault of these defendants.”

Rommel, the Ludwigsburg prosecutor, believes prosecutors must press on with these investigations for as long as possible. “We are giving the chance to the accused and the witnesses to tell us their stories—and not just to the media, they are telling them in a courtroom,” he says.

Weiss agrees. She points out that Hanning is getting a thorough trial—far more consideration than the hundreds of thousands killed at Auschwitz ever received. Speaking in court also gives her some chance at closure. She was asked to testify in the Hanning trial because she was part of a large transport of Hungarian Jews to Auschwitz during the period when he was a guard. After losing 22 family members in the war, she emigrated to New York to stay with distant relatives, where she had no choice but to move on with her life, without so much as a funeral for those lost. “I wish that he had been tried much earlier,” Weiss said in February. “But at the moment, I just want him to hear from me and the others who testified what the consequences were of what he did at a young age, and let him reflect on it.”

On April 29, Hanning finally broke his silence. “I want to say that it disturbs me deeply that I was part of such a criminal organization,” he told the court, according to the AP. “I am ashamed that I saw injustice and never did anything about it, and I apologize for my actions. I am very, very sorry.” But that wasn’t enough for Weiss. “A whole generation of Germans, the children and grandchildren of the perpetrators of the Nazi genocide, have heard nothing from their parents and grandparents about what they saw, and what they did, in Auschwitz and the other factories of death,” she told TIME after Hanning’s testimony. “It is time, at long last, to stop forgetting and suppressing.”

Perhaps the real value of the trials lies in the way they show that the Holocaust was the product not of a conspiracy of extraordinarily cruel individuals, but rather the ordinary actions of ordinary people. “They remind us that this genocide would never have taken place without these lowly foot soldiers,” says Douglas. “Things can go wrong in a hurry in countries, and when they do, it is shocking how willing people are to go along with it.”

With reporting by Merrill Fabry/New York

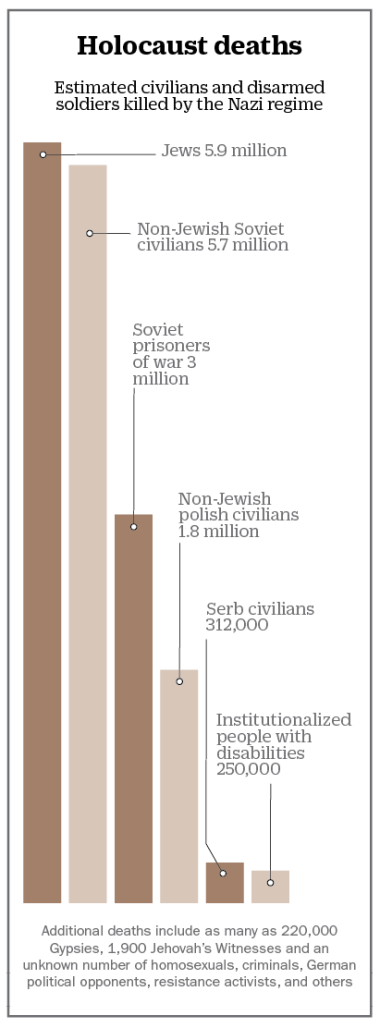

Graphics Sources: Historians Edith Raim and Andreas Eichmüller; Efraim Zuroff at The Simon Wiesenthal Center; U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum; Anti-Defamation League