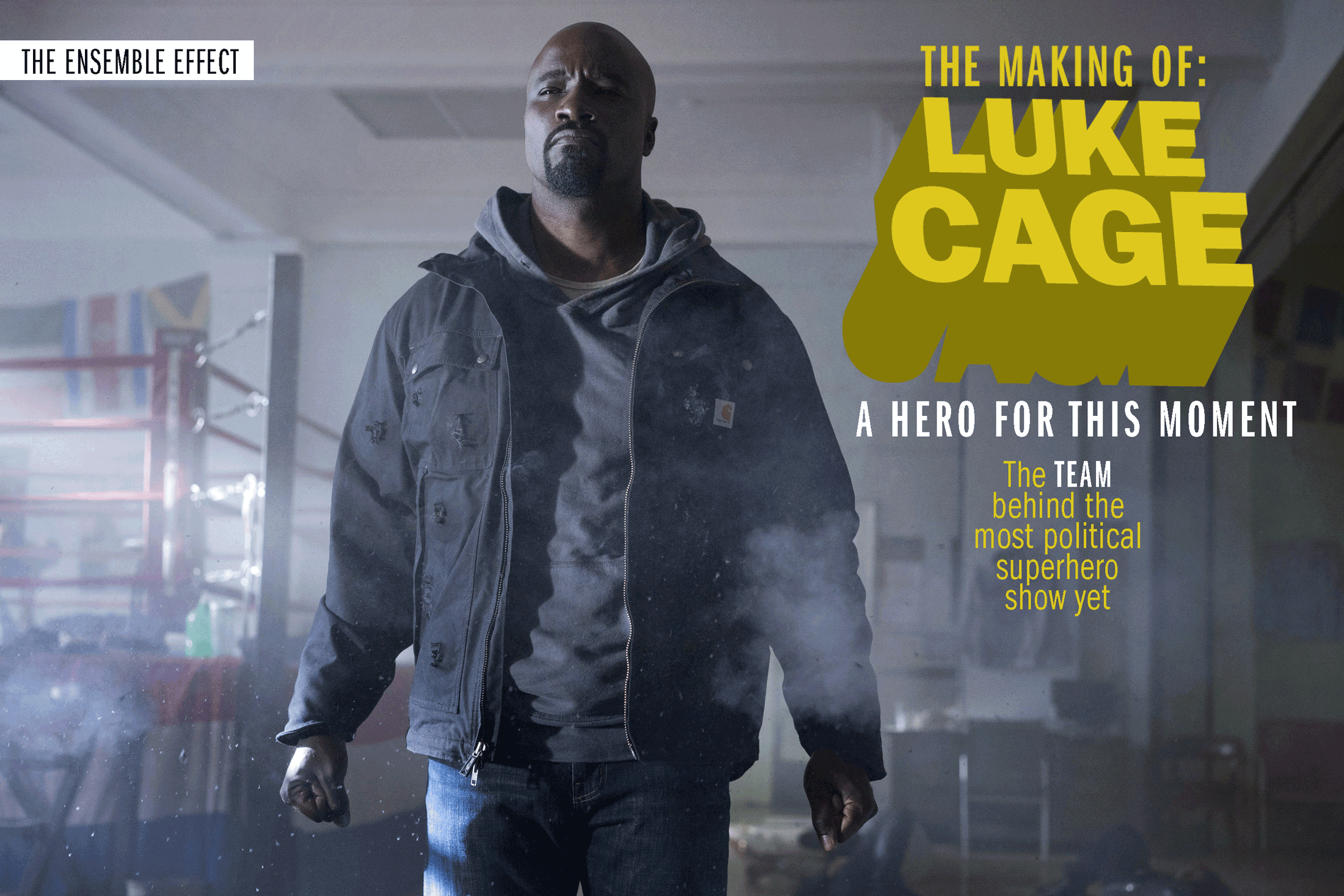

A bulletproof man hides out in Harlem.

The wrongfully convicted ex-con with superhuman strength wants to keep a low profile but soon finds himself caught between a trigger-happy crime lord and an intrepid police officer. Despite his misgivings, he uses his body to shield the neighborhood from stray bullets in the battle between cops and criminals.

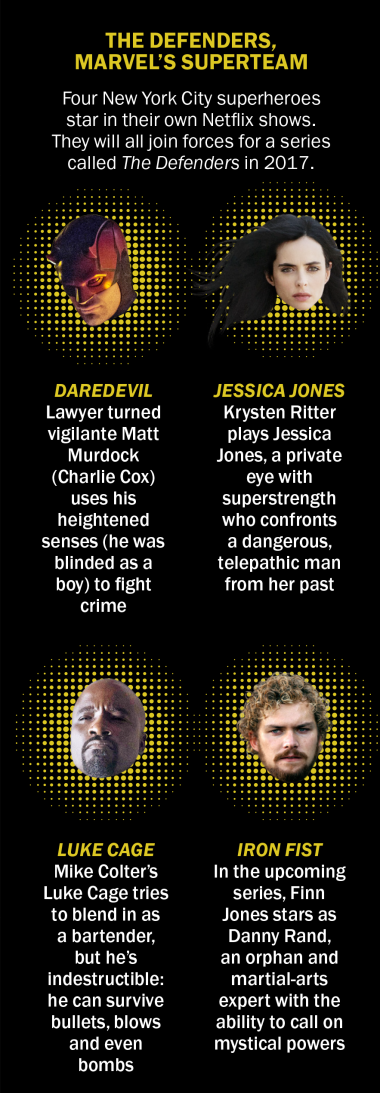

This makes Netflix’s newest protagonist, Luke Cage, an inherently political hero. Born in the pages of Marvel comics in 1972 during the boom in blaxploitation films, the man immune to bullets has taken on new resonance in the era of Black Lives Matter.

The Team behind Luke Cage

Superheroes don’t usually lend themselves to pointed social commentary. But the executives at Netflix and Marvel knew that bringing their first black-superhero show to the small screen would require more than awe-inspiring CGI explosions. In his first meeting with the streaming service, creator Cheo Hodari Coker won the job by pitching the series as an examination of Harlem, “like what The Wire did for Baltimore.” In order to achieve that goal, he would need to assemble his own team that would be able to capture the vibe of the New York City neighborhood.

Netflix greenlighted Luke Cage (it premieres Sept. 30), and Coker has kept his promise to Harlem. He tapped music producers Adrian Younge and A Tribe Called Quest’s Ali Shaheed Muhammad to score the show and recruit artists like Faith Evans and Raphael Saadiq to perform at the villain’s fictional nightclub. He instructed the prop master to carefully choose a selection of books for Luke’s bedroom, including a copy of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. He gathered a diverse set of writers to conjure barbershop debates over the Knicks’ lineup.

PLUS: How the Cubs’ Kyle Hendricks became an ace

“I called our writers’ room the Danger Room,” Coker says. “In X-Men, the Danger Room is this place where the X-Men train and fight each other and work out their powers. Our writers’ room was majority African American—which is a rarity on television—but it was also diverse in every way. When it came to ideas, everybody had their own power. There was beautiful conflict when it came to story.”

And rather than avoiding controversy, Coker’s team runs right at the turmoil of 2016. A local politician campaigns in the neighborhood with the slogan “Keep Harlem Black,” in the face of gentrification that threatens to homogenize Harlem’s rich cultural history. Characters clash over the use of the N word.

The noble hero dresses in a hoodie, a nod to Trayvon Martin and a visual argument against the assumption that a black man in such clothing is threatening. “What if you introduce a bulletproof character into a social ecology that isn’t bulletproof?” asks Coker. “How does he affect the police? The streets? People in the neighborhood who have turned a blind eye to crime in order to survive?”

Coker, 43, compares himself to a football coach and the writers to his coaching staff. (His roommate at Stanford was David Shaw, now the head coach of that school’s football team.) In a TV show, Coker says, “dialogue is the offense and structure is the defense.”

If so, actor Mike Colter is the quarterback. Colter, who broke out in Million Dollar Baby and has starred on The Good Wife and The Following, turned down many roles that he felt perpetuated the same black tropes. “I didn’t know whether I was going to be successful in this business because I think you have to ignore the fact that sometimes you’re strictly a stereotype or at the very least you’re not doing anything to undo a stereotype,” he says.

Not so for Luke Cage. Beginning with his first appearance in an earlier Marvel-Netflix collaboration, Jessica Jones, the Luke Cage character has defied convention. Luke becomes involved with a superhero named Jessica Jones, who is white. While most shows might ponder the differences between the two characters’ backgrounds, Jessica Jones treats the couple like any other, a tact Colter found refreshing. “I was tired of seeing interracial couples that shared a bond over alcohol or drugs or something deviant,” says Colter. “Every other version I’ve seen of that relationship reinforced this idea that there was something strange about an interracial couple. But Jessica and Luke make a real, authentic connection that has nothing to do with race.”

Luke Cage diverges from the pattern in other ways. Luke is a physically imposing man hesitant to use his strength. He carries himself with integrity and ease. He’s thoughtful and reserved. Even his theme music combines hip-hop beats with undertones of blues and jazz. He uses his comic-book-originated one-liner “Sweet Christmas!” sparingly, opting instead for pensive silence. The show’s palette is brighter, the music throbbing with energy, the themes “unapologetically black,” says Younge. “He’s a black superhero, but he’s a different type of black alpha male. He’s not bombastic. You rarely see a modern black male character who is soulful and intelligent.”

Music was the show’s glue. Colter and Coker first bonded over their love of ’90s hip-hop groups like Public Enemy, Wu-Tang Clan and A Tribe Called Quest. Coker, who interviewed and befriended A Tribe Called Quest’s Muhammad some 20 years ago during his time as a journalist, recruited the legendary producer to create music for the show. They used the lexicon of music as a shorthand on set, referencing obscure songs to define the vibe of a scene.

“I never wanted it to feel like a cliché: Let’s use hip-hop because it’s black urban social,” says Coker. “No, it had to be hip-hop from a certain area that resonated.” For Luke, that meant fewer loud anthems familiar to shoot-’em-up scenes and more hip-hop with the stirring sounds of jazz and blues at its core.

Muhammad says he and Younge jumped at the opportunity to help set the tone for a hero they believe America needs right now. “Given the conversation around police brutality, to get a call to do something like this related to a very positive black superhero who is bulletproof and trying to make a difference in his community—that’s the opportunity of a lifetime.”

The issue of police-community relations is central to this show. Simone Missick plays Misty Knight, one of Marvel’s few black female heroes. A by-the-book cop, Misty clashes with vigilante Luke about the best way to dole out justice. While a modern version of Misty could be portrayed as either corrupt or naive, the writers created a character who was more nuanced than that. “You’ve got this woman who is a cop and believes in the system at a time when it’s difficult to believe in the system and believe in justice in the traditional sense,” says Missick. “She has ideals that are not popular, on- or offscreen. But Misty is such a believer in doing things the right way and making a difference by being a cop and doing her job with integrity.”

Misty’s main target is the gangster Cottonmouth (House of Cards’ Mahershala Ali) and his cousin Mariah Dillard (Alfre Woodard), a corrupt politician. Coker persuaded Woodard, who lives in Harlem, to star in the show by proving his love of the neighborhood and its culture.

For her part, Woodard calls Coker a “student of the Harlem Renaissance, of the history of Harlem.” She says, “He traces the roots it took and the branches that have reached out across the world in terms of influence. The reason Luke Cage succeeds is that even though Luke has superpowers, it’s grounded in that reality.” That grounding includes discussions about white flight, the legacies of such icons as Zora Neale Hurston and Crispus Attucks, and the disruption that urban planner Robert Moses’ massive projects in the 1960s and ’70s caused for thousands of black New Yorkers.

Coker looked inward too, drawing inspiration from his grandfather, a Harlem native who became a Tuskegee Airman and was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. “He used to say that at a time when it was purported African Americans didn’t have the mental capacity to fly airplanes, they knew the stakes were as profound at home as anything they were dealing with in the air or being a part of a segregated unit,” says Coker. “I’m not going to be one of those people who says, I’m a showrunner, I’m not a black showrunner. I’m black when I go to sleep. I’m black when I wake up, period. It doesn’t affect my perspective on everything, but at the same time, it’s who I am, and I’m proud of it.”

Coker knows that like his grandfather, his crew has the opportunity to make history.

Correction: The original version of this article misidentified the age of Cheo Hodari Coker. He is 43.