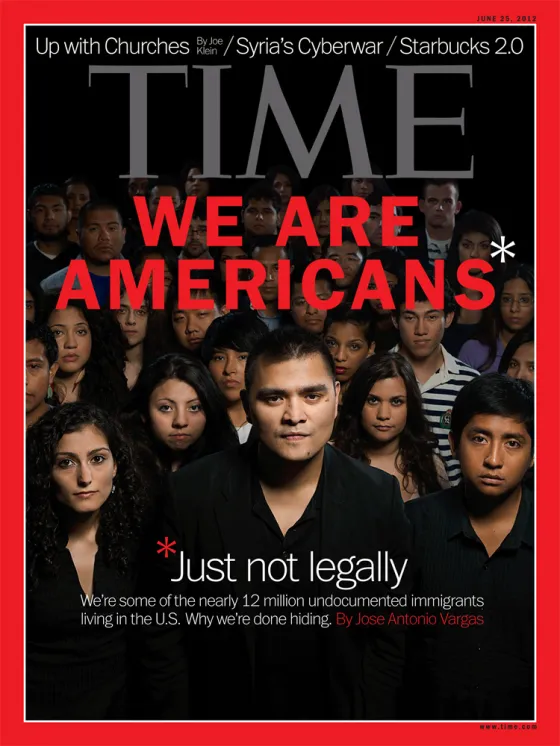

We Are Americans, Revisited

the dreamers, five years later

By Maya Rhodan and emma talkoff | Photographs by Gian Paul Lozza for TIME

In 2012, TIME worked with journalist and activist Jose Antonio Vargas to share the story of America’s Dreamers—undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. illegally by their parents. The day the story was published, President Obama enacted the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, or DACA, which has shielded some 800,000 immigrants from deportation and freed them to take jobs, get an education and live the American dream they’d always claimed as their own. Since that time, many of the 30 immigrants who appeared on TIME’s cover have gone on and finished school, started families, traveled abroad and become engaged citizens. One, Roy Naim, chose a different path and is currently serving a 15-year prison sentence for possessing child pornography.

Now, their future is in doubt. There are reports that President Trump may end the program, despite repeated statements during the campaign that his immigration crackdown would not extend to Dreamers. TIME got back in touch with 15 of the 30 people who appeared on the cover to see how their lives have changed since DACA and what they are at risk of losing if the program ends. Some did not want to be included; others simply didn’t respond. Here are the stories they shared.

Julio Salgado

For almost a year after DACA was passed, Julio Salgado avoided applying. Like many immigrants who qualified for deferred action, Salgado was plagued by guilt at the thought of friends and family members who didn’t make the cut. Today, he’s channeling the emotions and uncertainty that come with navigating the immigration system into artwork and filmmaking.

What was it like for you when DACA was signed?

It was a very celebratory moment, but at the same time, there were people like my parents who did not qualify. It was just heartbreaking. If you don’t qualify for a piece of paper, that means in the eyes of the public and the immigration system, you’re not human. That to me is the heartbreaking part.

How did the conversation with your parents go when you told them you were hesitant about applying?

I told my dad, “I just feel really guilty.” And I remember crying to them, just crying and feeling how unfair it is that our parents don’t qualify. And he was like, “Dude, get it together, quickly. You need to go ahead and apply.”

I was coming at this from a very idealistic perspective—like no, it’s not fair, I’m not going to do it. Yet my dad, all his life he’s had to work difficult jobs. And he was like, “If I could apply for DACA and get a better job, I would. You’re kind of wasting your opportunity to be able to do that.” It was a wake-up call to me and my idealistic self, and being like, you know what, I wish it wasn’t like this, but this is what we have.

What kind of work have you been doing since DACA?

It sparked something in me. As an artist, it is my duty to document what’s happening, but at the same time I want to document happiness of my people, the resilience. Up to that point I was doing all these images about stopping deportation and while that’s very much needed, I wanted to create something that was giving people hope.

We’re constantly seeing all these images of the person getting arrested by immigration and the sadness of it all. For me, it’s important to put out stories and create art that give me a three-dimensional narrative that a lot of times I don’t see.

Erika Andiola

In 2010, Erika Andiola became one of the first undocumented people to work as a congressional staffer. Then, in 2015, she made headlines when she was hired as a strategist for Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign. Andiola was working on immigration rights issues that she had fought for for so long—and now she was drafting them into policy, even as she fended off deportation orders for members of her family.

How have things changed for you since the election?

They have been different. I speak a lot about the deportation machine that Obama created, but I feel like we had a little bit of a better chance of stopping deportations because there was sort of a moral argument to be made. He was a president who ran on a platform of stopping separation of families and for immigration reform. But when you live under this new president’s rhetoric and agenda, which is, “I will work to deport everybody and their mom,” basically, everyone that I can deport, mentioning the Latino community and the Muslim community—I think for my mom and I it’s just a little bit harder to figure out how to make that argument for her to stay.

How did you get involved in political work?

When I came home from the interview [for a job as a congressional staffer], it was the same day that my mom was raided. [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] took my mom and they took my brother. I was kind of ready to step a little bit away from the Dreamer movement and the organizing world and focus in the Congressional office, but my house got raided, so I basically was organizing at the same time that I was working for a member of Congress on the topic of deportation.

What has it been like fighting to keep your mom in the country?

It’s exhausting. I feel like I have to always put a stop on anything that I’m doing, every single year, to figure out how to fight for her again. I am an organizer, so to now take in all the different things that Trump is doing and politically try to push back, and at the same time understanding that I have to make some time in October, for example, when she goes back to court, and November when she goes back to ICE, I have to just drop everything and go back home to support her emotionally but also figure out legal strategies to keep her here. It’s exhausting.

‘am i going to lose everything?’

Luis Gomez

In the years after DACA passed, Luis Gomez visited high schools across Massachusetts to educate undocumented students about the program and encourage them to apply for college. He was also able to return to an engineering apprenticeship where he’s working to get an electrical license. Now, he’s waiting for an important piece of mail—confirmation that his DACA renewal has been approved. Gomez is part of a mixed-status family, and says that he’s the only one without secure paperwork. He’s keeping his family in the dark about the renewal to keep them from worrying, but it’s been tense.

What changed in your day-to-day life after you were approved for DACA?

It was very surreal. The biggest thing for me was when I got my driver’s license. Studying for the test, passing the test on the computer, and the driving test—just the process, and then getting my driver’s license and driving. That sense of freedom that I could drive, and if I’m pulled over I know it must be justified somehow, and if I did something bad then I know that the cop isn’t going to write me up for something that I can’t say anything about. That was amazing.

What is it like talking about being undocumented at work?

It brings up this cool dynamic where I get to educate [my coworkers] on how I was undocumented. People keep saying, “do it the right way” or “get in line,” or something, but they don’t realize that some people don’t have a line to go through, and there isn’t a right way to do it.

I had this one coworker and he seemed very inquisitive—I was telling my story and how I came to the U.S. and how DACA happened. Break time came around and he said, “Oh no, you have to tell me how this ends,” because he’s never heard anything about this before. He was just shocked by the reality.

Are you nervous about renewing your DACA status?

At first I wasn’t, but now I am. I’ve been calling and they’re saying it’s fine, but it might not be fine. When I talk to the person there, it’s another Tuesday for them, but for me it’s like, am I going to lose everything?

Tania Chairez

After stints as a teacher and community organizer, Tania Chairez settled in Colorado, where she advises college students who are navigating the immigration system. Right now she’s extra busy—in September, she’ll be working with KIPP Colorado Schools to help students with DACA in their pursuits in higher education and the workforce. As part of her work, Chairez makes “know your rights” emergency plans with parents and students—worst-case-scenario outlines for how a family will survive if some or all of them are deported. She’s made one for her own family too.

How have things changed since the election?

I think one of the biggest things that has changed even since the election has been just the fear in our community. The sad part for me is I left Arizona trying to leave that anti-immigrant rhetoric, and we came to Colorado thinking that it would be better. But now it’s like Arizona is everywhere, it’s nationwide. I’m seeing a lot of the experiences that my family and I went through in Phoenix here in Colorado.

Have people in your community had to change their behavior?

All of it. There are families that I’ve talked to who are terrified to take their kids to school, and so even just dropping them off at a bus stop is scary for them, and they’ll take a different route every time they drop their kids off just to see if that makes a difference. Here in Denver, we have a very big immigration agent presence in our court system, so for anyone who’s trying to fulfill their probation requirements, or DUI classes, domestic violence classes, whatever kind of thing you have to do in the court, people are scared to go to the court because ICE agents are very likely to be there. We’ve even warned schools about this, and we’ve let them know that if they have any undocumented students who are undergoing truancy charges, to see if they can avoid the court systems, because it’s not just giving them a ticket like it would be for any other kid. It’s like giving the family a deportation sentence.

What’s it like making emergency plans with families?

It’s terrifying. I had to do a “know your rights” training for little children, for a second grader and sixth grader and a seventh grader. I had to transform all my materials to child-friendly language and have them draw pictures and things. At eight years old, they have to be thinking about emergency plans and who they can open the door for.

They reacted very much like young students would, where they would keep asking questions like, “Can’t we just hide? Can’t we run away?” I had to remind them like, no, you can’t really hide, you can’t run, you can’t lie, that’s not how this works. It was also frustrating to see that they were having to think about going to counseling. Those students have to be watching their back every single day, every single moment, and every time their dad goes to school and drops them off, they don’t know if he’s going to be there when they get back.

‘something I have in my mind every day’

Juan Pablo Orjuela

Juan Pablo Orjuela says he’s always known a day would come when the relative protections and conveniences provided by DACA were under threat. Right now, Orjuela is a full-time volunteer with the immigrant rights organization Cosecha. He’s always wanted to go back to school for engineering, but for now, there are more pressing matters to consider.

Did DACA make you less afraid?

For me, being involved in organizing, being very involved in immigrant justice, that’s never changed for me since DACA came out. Yeah, it made a lot of things in my life easier, but having fear has never gone away.

The thing is, my original objective was to become an engineer. Before 2012, I was stopping deportations while I was going to school, I was doing all these things, and I kind of kept continuing it [after DACA passed] because it was a need that we still felt as a community. I had that understanding that DACA was just temporary. And I carried that along with me, which is why I kept going into organizing. Because even with DACA, I didn’t feel safe, it just made things easier.

How did things change after the election?

The election I think for me brought out feelings of things I’ve known for years that deferred action was never a permanent solution. I found myself getting really comfortable with DACA, but after the election and especially with what’s going now now, it’s just kind of bringing up those feelings again. And I’m just kind of like, “Oh no, what am I going to do now?”

Do you ever think about going back to school for engineering?

I always think about going back to school. That’s my hopes and my dreams, part of why I’m in the fight. I paused my life. Now I do it less for myself and now I do it more because I’ve become so embedded in the immigrant community, in more ways than just being a part of it. I feel like I can’t stop or leave until there’s full, permanent protection for immigrants. But even now, I know I can’t go to school, but I try to keep up on studies and advances and current technology.

It’s something that I have in my mind every day and it’s something that I incorporate into my everyday life, it’s just that it’s so difficult to make that be a priority. What’s the point of an engineering degree if I’m on the verge of being deported the next day?

Lucia Allain

For Lucia Allain, the immigrant rights movement is wrapped up in complicated feelings. The movement is both her “family,” she says, but also a place where she’s always felt alone—because she was always working, even as a middle schooler, and often combating extreme poverty, she was never a good student and felt alienated by the image of the academically perfect Dreamer who “had it all together.” In some ways, things have changed a lot for Allain since DACA passed. In 2013, she became a permanent resident of the United States, and, just last month, a citizen. But the fear that came with being undocumented has never really gone away.

How was life different after you became a resident?

Getting my status didn’t really change anything at home, because my brother is undocumented and my mom is still undocumented. So my status changed, but my problems were not solved.

It’s pretty obvious once one person becomes legalized, it doesn’t change your whole family, but in my head I thought I could bring some sort of safety. Now I know longer think of it like that. I’m glad I’m a citizen and I’m glad I have many more rights to vote in the next election and do other simple stuff—a nine-digit number changed my life, but it didn’t really change my life.

I don’t want to say that I regret, but it pains me to know that I’m the only documented person in my family. It makes me feel guilty. Why should I deserve this when other people who are in a worse situation could deserve this more than me?

How did things change for your family after the election?

When Trump came in, it was even worse. The fear really increased. The idea of New York being a safe place got out of our minds. We went from so much New York pride, “Come here, you’ll be fine here, you’ll be safe,” to “We don’t know if this is safe anymore.”

Have you had to change your day-to-day life?

There’s a rule that we can’t walk my dog after ten because it’s too late, something could happen. We have two locks in our door, we added a new one because my mom was super afraid. We’ve talked to our landlord about our gate downstairs to make sure that was fixed and no one else could get in.

The fear has gotten to me, where if I’m traveling for the weekend, I’m the one telling them, “You need to make it home before sundown, you guys need to lock up all the doors.” Our safety conversation went from, “Yeah, come home whenever, give us a call,” to “Make sure you’re checking in.” We get to the house, we tell our mom we love her, we leave the house, we tell our mom we love her. The fear has increased to the point where we’re like, “I love you, and anything that goes wrong today, just know that we’re near home and everything will be fine.” It’s become like a routine or a ritual, where every day there’s an “I love you” out the door, coming in the door, through text messages, through calls.

Cesar Vargas

The immigrant rights movement is divided on whether activists should try to make change by aligning themselves with political candidates, but for Cesar Vargas, who joined Sanders’ presidential campaign in 2015, it was “the logical next step to our advocacy.” Vargas has also found other ways to advance the movement, which he says is evolving. In 2015, after an intense legal battle, he became the first undocumented lawyer in New York.

How has your life changed since the election?

For me, it was just kind of an urgency that needed to be addressed, and fortunately I was able to, with my law license, after a four-year legal battle. I went from being an advocate-slash-organizer-slash-activist to a lawyer. I’m still learning from that.

Now people are saying “Can you help me with my deportation proceedings?” For me, that trajectory from an activist, an organizer to now a lawyer really reflects the progression of a movement that we’re seeing now, from students who were just lobbying in Washington, D.C., to professionals, key political players in our community. It’s something that I didn’t expect for sure, to know that there is a whole community looking to you for your leadership.

What changed for you after DACA passed?

It was like day and night. From not having a driver’s license and being very careful, very vigilant every time there was a police officer … it was mostly an uneasiness that maybe some people don’t have to go through, especially just driving or travelling with your passport to another state. With DACA, I was able to get my driver’s license and travel in peace. With the papers, I was an American, and this is my home.

Have your personal experiences with immigration helped you as a lawyer?

For sure. I think from the personal, I can definitely connect with many of my clients in a very, very different way, a deeper level. One case, this was a child who had immigrated to the U.S. by himself. The first time I had met him, he was very reserved, he was very shy, he didn’t trust me yet. After almost a year and a half legal battle, he was talking about his girlfriend, he was talking about prom.

It was just so incredible to build that kind of relationship, but it was because I told him my own story. He understood that I’m trying to get him immigration status so he can live his dreams. For me, that was an incredible experience. I know the consequences of winning a case—it’s people’s lives.

‘those ghosts would come back’

Daniela Bravo-Terkia

Daniela Bravo-Terkia came to the United States from Chile in 2000, when she was 12. Although she was initially hesitant about DACA, she applied in October 2012 and was granted her permit in 2013. She has renewed DACA twice, once in 2015 and again in 2016. Now 30, she graduated in December from University of Massachusetts Boston, where she was valedictorian and recipient of the John F. Kennedy Award for Academic Excellence, the highest honor given to an undergraduate. Before DACA, she was in school but paying out-of state tuition, and had several semesters where she didn’t attend because she couldn’t afford it. DACA helped her get in-state tuition and a job as a research assistant. She hopes to earn a doctorate.

What changed for you after DACA was signed?

DACA was announced in June of that year, 2012 and people didn’t start applying until August, but I was a little late. I was scared for my mom. I said, they are going to know information about me, so they are going to know information about my mom. And then when I started hearing about all the people getting it, that motived me to apply.

I remember getting my work permit in the mail. I said to myself “Oh my God, it’s here.” My mom was working early in the morning so I called her. I said “Mom, you won’t be able to apply for this,” and she said, “It’s OK, all I care about is your happiness.”

Later that day at work, I told a friend about DACA, and she didn’t qualify either. So by the time I got my deferred action, I had mixed feelings about it. It created this notion of “Why me and not other people?”

What were you doing before DACA?

I was going to school, paying out-of-state tuition. I was taking one or two classes at the time, and I was taking off semesters because I couldn’t afford it. Massachusetts did not have in-state tuition for undocumented immigrants, so I had to pay out of pocket. And I was usually late in my payments so I usually owed a lot of money. I did multiple jobs—cleaning, restaurants—trying to finance my education that way.

How would your life be affected if DACA were ended?

I feel extremely anxious. I don’t know how my life will be changed. I wouldn’t be able to continue my work at UMass Boston, my independence would be compromised. I have goals of going to graduate school and I don’t know if I can take putting those dreams on hold again. Because it’s like for me it would be like a huge rewind. And there’s something we don’t talk enough, is my mental health would be extremely compromised. Anxiety, depression. In the past I’ve had suicidal attempts because the stress of the situation is too much, it’s too real.

You’ve had suicide attempts?

One. When I was undocumented. So I feel like all of those fears, all of those ghosts would come back to my life.

And not only that, we’re talking about leaving my whole life that I created in this country, and starting all over again in a country that I don’t even know. I left my home country in Chile when I was 12 years old, and now I’m 30.

‘Dreamers have always been a political football’

Carolina Bortolleto

When DACA was first implemented, Carolina Bortolleto was so busy helping others apply through an immigrant rights organization where she was working at that she didn’t submit her application for the first three months. When her work permit was approved, she began saving for graduate school, got a driver’s license and bought her first car, a 2012 Ford Focus. In 2014, she suffered from a medical emergency that resulted in nine surgeries and a feeding tube. As an undocumented immigrant, she didn’t have medical insurance. Her twin sister, friends and allies turned to crowdfunding platforms in order to pay the bills. When she renewed her DACA permit the next year, she filled out the paperwork from her hospital bed.

What were you able to do with DACA?

So much of my life had been planned around what I couldn’t do. Having opportunities that were available to me, it was another world. In the fall of 2014, I started graduate school for a master’s in public health from George Washington University. I was taking online courses because I didn’t want to leave Connecticut. My goal was to start online and if I liked it, transfer to the campus.

The biggest impact it had in my life was getting a driver’s license. I was never able to get a license before, so I was always dependent on other people driving places or public transportation, Even though I was 24 when DACA came out, I never really felt independent. My driving school instructor saw that I was not the usual 16-year-old, so I mentioned that I was getting my driver’s license because of this new program. And he said, “Oh yeah, I’m getting a lot of students now who are able to get their driver’s license because of DACA.”

I got my license on Dec. 18, so my Christmas gift to my parents was my license. I put it in a big box and I wrapped it and then they opened it and saw the driver’s license. My mom started crying because she was so happy.

Did you finish school?

No. In December 2014, I had a I had a sudden gastric obstruction and then my stomach ruptured and I had a whole bunch of complications. Even though I had DACA, I didn’t have health insurance.

How did you pay for it?

We used community fundraising. I had been working for immigrants rights here in Connecticut and nationally since 2010, so I was already out as being undocumented. I worked at an organization here in Connecticut. I was also a board member of United We Dream group network. While I was in the hospital, my sister started a GoFundMe and she raised $18,000. That was not enough, but it was helpful. Then a lot of people in the community really helped. The social services organization I used to work for had a Zumba fundraiser. A local Portuguese language newspaper in my town also had a fundraiser. And for the rest, we worked with the financial services part of the hospital and applied for emergency Medicaid and worked to pay down some of the bills.

When you’re in the hospital you just kind of think that the world forgets about you because you’re so isolated. To have people in the outside world who were still thinking about me and helping me and they believe in me enough to invest so much of their time and resources—I was amazed and surprised.

How would you describe your life now?

The medical thing had a much bigger impact on my life than DACA. I think about my life before December 2014 and after December 2014. I feel like I only had DACA for a year. I only had that driver’s license through 2014 and with all of my medical devices I can’t drive anymore.

It was actually very fortunate that I started my graduate school online because I was able to continue what I was doing. Once I got out of the hospital, I started taking classes again in 2015. The only thing that makes the process slower is the funding, because as an undocumented student you can’t get financial aid and my school didn’t have any aid available to give undocumented students. I’m mostly just applying to private scholarships. I think I’ve applied to over 80 in the past year alone. I’m only able to take one or two classes at a time.

Does the Trump Administration’s approach to immigration make you nervous?

Dreamers have always been a political football. We’re described as the most sympathetic of immigrants, the ones most people can get behind so we’re always being used as a political bargaining chip for other government measures which is a shame. DACA is not a permanent solution. I always saw it for what it was, a temporary work permit. To me, DACA is a great thing, but it really isn’t enough. Which is why I’m committed to keep fighting for immigrants rights.

‘if you’re older, you’re not as valuable’

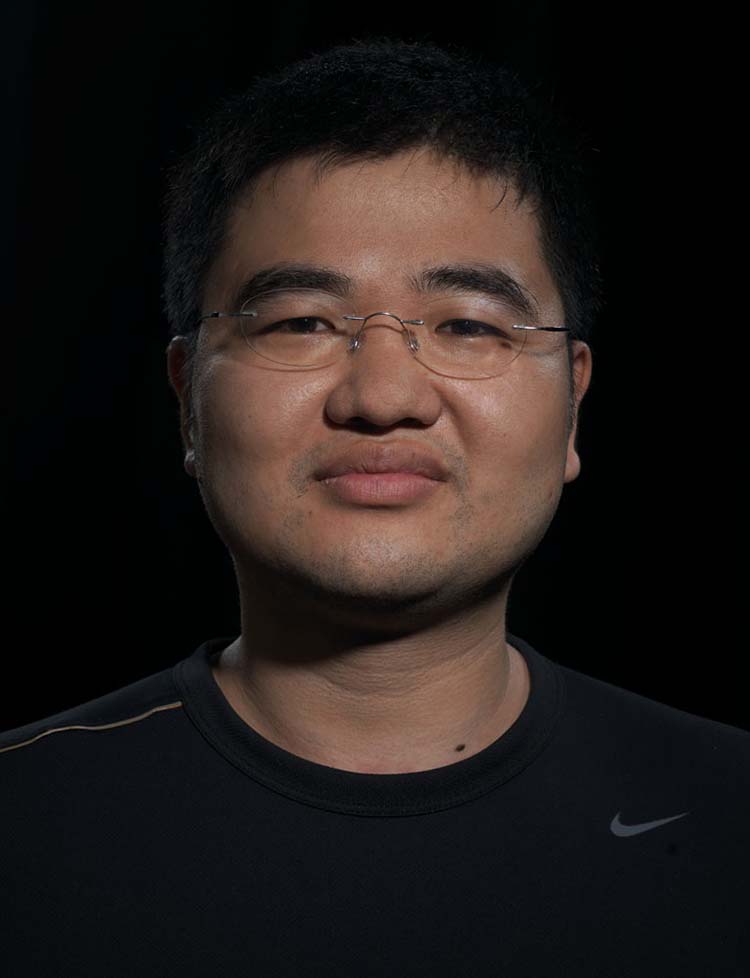

Jong-Min

For Jong-Min, not much has changed since 2012. Since he was too old for the DACA program, he remains undocumented. Now 37, he still hopes that he’ll eventually be able to become a citizen of the United States, the only country he’s ever called home. If he were to become a citizen, his goal would be to attend law school and eventually become a federal judge. For now, he’s working in his parent’s grocery store in Brooklyn.

How did you feel when President Obama announced DACA?

I was happy for everyone else. I know that I had lived in the shadows just like they did. A part of me was hopeful there would be something for the rest of us. I was hoping that people would get on board with an expanded DACA, but there wasn’t enough movement. I don’t think people cared enough about the people like me who just aged out. As time went on, I thought, like, we should have something for me and everyone else. It led to become feel disappointed and angry, as well, because it felt like they just kind of forgot about us. It seems like if you’re older, you’re not as valuable. I don’t understand why people couldn’t give us a chance as well.

Have you adjusted your status since then?

In the last five years, on top of the 27 years before that—32 years now— I still haven’t been able to adjust my status. For those who aged out or for those who don’t fit the specific narrow immigration requirements, there’s no pathway.

Why do you think it’s important to still speak out?

If South Koreans could band together–if we could all band together, we could get public support for this and maybe pass legislation. That wouldn’t be just good for me, Jong-Min, but for my neighbor, for the Mexican landscaper, for their kids and their wife, or the meat packer or the factory worker, and people we all know who may be undocumented. If you’re ashamed and never talk about it, I don’t think you can get support. I hope that my being public helps people realize that this is a problem that we have to work together for a solution so that other kids are able to live the American dream. That’s why we’re here. That’s what we want to do.

‘it feels like a threat to all that we did’

Renata Teodoro

It took a while for Renata Teodoro’s DACA to get approved. She applied shortly after the applications became available in August of 2012, but wasn’t approved for a work permit until March. The anxiety she felt was so overwhelming that she petitioned her U.S. Senators to ask what was taking so long. When she finally got approved, she was able to do something she hadn’t done in six years: hug her mom, who had been deported back to Brazil in 2007, by using an immigration travel program called advanced parole.

Once you got your DACA paperwork, what did you do?

Once I was able to get my DACA I was also part of a national action [event] on the border in June 2013 and I was able to use my DACA to go through the checkpoints at the border in Arizona to meet my mom at the border with two other people. The last time I saw my mom before that was Dec. 26, 2007. I think it would have been way more difficult to get close to the border without DACA.

It was bittersweet. It was a much harder moment than I thought it would be. It wasn’t like, a real reunion. Seeing my mom through the fence was just heartbreaking. But DACA helped me make that somewhat possible.

How did you make that trip happen?

This idea had been floating around for a while, and when I was approached, I jumped at the opportunity. When I first told my mom about it, she completely agreed with it. She was like, whatever it takes, I’ll do it. I just want to come see you. I just had to figure out her passport–had to give her money for a new passport, and I told her we would fundraise for the tickets because the tickets from Brazil to Mexico were really expensive. It was almost $2,000.

The trip took a huge toll on her health. My mom kept passing out from a combination of the heat and the stress of having to see me like that. When she went back to Brazil she ended up in the hospital and had to take medication to lower her blood pressure. For a long time I felt really guilty about bringing her to the border. I was just so desperate to see her that I didn’t think about all of these things.

Have you seen your mom since?

After I came back from the border I became really upset and made it my mission to figure out how to actually reunite with my mom for real, where she’s not crying behind a fence. I couldn’t keep doing that to my mom. She really was just depressed because she couldn’t see me, and my brother and sister were kind of upset about the physical toll it took on my mom. I thought, I have to figure out a way to see her. Advanced parole was kind of new back then. I talked to two lawyers and they said they didn’t think it was a good idea to do it right then, but I just had to do it. I knew if I took the chance, I could see my mom. So I took the chance.

There are very specific requirements for advanced parole: Humanitarian, a sick or dead family member, education purposes like study abroad and work-related reasons. I thought that the best option for me was work-related. So I figured out who would be interested in having me speak in Brazil so I that at the same time I could reunite with my mom. In December of 2013, I was able to see my family in Brazil. That was really great. That’s been the most significant thing that DACA has allowed me to do.

What does your family think of your advocacy?

At first, my mom wasn’t exactly the happiest about my involvement. She was really upset about my brother, who had been detained. He came to the U.S. when he was nine so she blamed herself a lot for it and it made her really depressed. So when she left and all of a sudden I was being involved in this movement and being open about my status, she was really upset that another one of her children was going to end up in jail. But after the TIME magazine cover came out, she told me that she was really proud of me. She told me, you know what, keep doing what you’re doing. You know better than any of us. That was a really good moment for me, when my mom finally accepted what I was doing.

How often have you traveled?

I went to Brazil four times. I’ve also got to go to the U.K. and I did some presentations in Scotland and went to Paris and Italy. I was doing all of these things that I never thought I would be able to do.

I decided to go to Brazil in January, which a lot of people advised me against. But I had to go one more time before anything changes. I came back on Jan. 29. In Brazil, they’re usually confused about what advanced parole is, but once I explain it they usually let me on the plane. This time around, when I got to the airport in Brazil, I got pulled aside taken to a separate room and they went through my stuff. And they patted me down and they asked me questions. They said I was randomly selected based on extra screening that was going on in the United States.

When I got to the United States I had to go through the same process again. I was sweating bullets.

How have those experiences affected you?

When I traveled to the U.K., I had meetings with other undocumented young people. They were telling stories about coming when they were young, not understanding the immigration process, wanting to go college. It felt strangely similar.

This year has also been really difficult because the threat to DACA doesn’t just feel like a threat to my existence here, but it feels like a threat to all that we did.

What are you doing now?

Applying for jobs and keeping myself busy by staying in touch with students. Helping other students try to navigate college. Taking time to read or go to the beach with friends. Increasingly I’m getting more anxious because I didn’t realize how long the job process is—how long it takes people to email you for a resume or set up an interview. I’m just hoping that I get something soon.

When my family was deported, I was just out of high school, but I was able to figure out how to live on my own and survive. I’m pretty sure I can survive this as well.

Tolu Olubunmi

Tolu Olubunmi one of three dreamers who appeared on the cover of TIME in 2012 who were too old for the DACA program, which cut applications off at age 31. But that hasn’t stopped her from advocating for immigrant rights, both domestically and abroad. Since DACA was enacted, she’s spoken at the White House, launched Immigrant Heritage Month and joined councils at the World Economic Forum and the United Nations’ International Organization for Migration.

What was it like to not receive DACA?

Having just turned 31, I knew that I would not qualify, but it was still an incredible victory that I celebrated. I came into immigrant rights not just for myself. It’s heartbreaking to watch Jose Antonio [Vargas] and thousands of others that I know lose out on DACA, but we continue to fight. The way I see this work is: There’s never a period, there’s always a comma. You keep going.

Did not having DACA stop you from doing anything?

A lot has changed since that TIME cover. In 2014, I had the incredible honor of being asked by the World Economic Forum to join their migration council, which is this invite-only brain trust of the World Economic Forum. I’ve been able through my work I’ve been able to have a platform to speak more globally, to work on issues affecting migrants and refugees around the world. I also co-chair a project on remote working as a 21st century alternative to physical migration for the council. I’m also now on the board of directors for USAIM for IOM, the United States based non-profit partner of the U.N. Migration Agency.

The lessons learned from working on the Dream Act in those early days led directly to my founding of my own organization, which is Lions Write. It’s based on my absolute favorite African proverb that says, “Until the lion learns to write, all of the stories will glorify the hunter.” In 2009, there was this rise of this coalition of the willing where dreamers were speaking out and sharing their stories and sharing our stories in our own voice. Dreamers really taught the lion to write.

Have you traveled for work?

The first time I left the U.S. since I moved here at 14 was in 2014 and my very first trip was to a World Economic Forum summit for my council. I was honored to be there and to be a part of this network of amazing change makers. I did get permission from U.S. immigration to travel on something called advanced parole. On your permission to travel, it says it does not guarantee your reentry. I have been out of the U.S. and back three times now twice to Dubai with the the World Economic Forum and once to Nigeria working with an international development and education organization.

Does traveling make you nervous, given your undocumented status?

There’s always that moment of coming back and thinking, alright then, what’s going to happen when I get to Customs. Am I in? Am I out? But the older I get and the more opportunity to do incredibly important work for millions of people, the more I recognize that my comfort shouldn’t be the first thing on my mind given the opportunity to change the lives that I see as being in worse situations than me. It is dicey traveling, but it’s something I do. Well, it’s something I did under the Obama Administration. With this new administration, with the Muslim ban, with uncertainty around what’s going to happen with DACA, with uncertainty about who’s in, who’s out, what are the rule, what’s going on—it is not something that I would encourage.

How has that affected the work you do?

My heart is to be, to do the work where the work is needed and not being able to be on the ground in many instance really creates a barrier from doing some of that work, but I’ve never been one to shy away from a challenge. Dreamers found ways to be creative and to change narratives and to make the seemingly impossible happen and so I continue to find ways to do that work.

What do you think the next five years will bring?

I hope that DACA remains, but I also truly hope that DACA is not all we have. Because DACA is not enough. There needs to be more. This work should not solely be focused on undocumented immigrants, the so-called “cream of the crop” of immigrants, the “deserving.” This work should go far beyond that. Focus on the legal immigration system and the fact that families are separated for years and decades. Focus on giving refugees access to safety in the U.S.

What is actually going to happen, I can’t say. What I know that I will continue to do is do what I’ve always done which is use my voice and defend those who are most in need of it.

‘all of that crumbled like a sandcastle’

Tony Choi

After receiving DACA, Tony says he realized that he could make plans for the future—something he’d never even thought about doing before. He went from making five dollars hour at a sushi takeout place to having health insurance and planning for retirement, while staying involved in the immigrant justice movement. He’s stayed active, helping organize the Women’s March and most recently joining in a protest during the NetRoots Nation Conference in Atlanta. His plan is to become a journalist and writer like his fellow Dreamer Jose Antonio Vargas.

How did your life change after DACA?

I realized that I wanted to really live for myself. I didn’t really know what that meant because prior to that, I never had the chance to ask myself what my life would be like if I wasn’t undocumented. I was just stuck on surviving day-to-day. I was a little behind some of my peers who were citizens because they’ve had so many opportunities, but now I could finally play catch up to them and be what I wanted to be.

I’m on the path to become a writer, but I’m currently working at a digital organization and working their social media and continuing to organize Asian-Americans.

What were you able to do?

I already had bank accounts prior to this, but being able to do things like have a job where I have health coverage, which was revolutionary. Growing up, I always had to avoid getting sick or try my best not to get sick. But all of a sudden I had sick days, I could go see doctors. When my tooth hurt I would go take Tylenol, but all of a sudden I had dental insurance and vision insurance. All of those things were very new and I got to think “Do I really have a future in this country?” I started planning for retirement. Prior to DACA, that wasn’t even really an option. When you don’t know if you’re going to be in this country 30 or 40 years from now, do you want to save money for retirement? Or put money in an IRA or 401(k)? I had to really catch myself up on being financially literate and set up a future for myself. After the election all of that crumbled like a sandcastle. The focus was no longer on me, 20 or 30 years down the road. It was on me tomorrow or me six months from now.

How did you react to the presidential election?

When Trump was elected, I was stunned. I didn’t really know how to react. I felt like, what is going on? I wanted to ask that over and over again. One thing led to another and I became a national organizer with the Women’s March on Washington. And the day prior to the inauguration, I still remember very vividly. I was at the venue where we were organizing and I asked the question to myself, why do they hate us so much? What is it about me that they do not like—the voters who elected Trump.

It just felt like a burn to my face and made me really question what was in my future. Do I genuinely have a future in America? I’m still trying to answer that for myself, but I do have a future in America. I’m trying to do my best to get to where I want to be in life. All of a sudden I realized that the ground that I was standing on was incredibly fragile.

For the long while, our advocacy language was always that–that folks with DACA had just a temporary protection. I’d been repeating that point over and over again, but from November until like January I really realized what kind of ground that me and 750,000 of my peers were standing on. We’ve entrusted the government with our information, and suddenly the government “of the people” is made up of people who do not like us. Who don’t want us to be here. And it’s been frightening, but I’m still trying to be realistic and focus on the day-to-day.

Victor Cuicahua

For Victor Cuicahua, DACA has been the key to an education he never thought he’d be able to access. College was always a dream, but one he thought impossible—his parents hadn’t finished middle school until they were adults, and growing up, admissions officers always told Cuicahua that he faced an uphill battle trying to get into schools while undocumented. But next year, Cuicahua is set to graduate from Pomona, where he transferred from the University of Alabama, and hopes to teach or work with students like him.

What did DACA mean for you?

My life totally changed. For one, I was the first undocumented student admitted to the University of Alabama. I still have my acceptance letter because that was something that I had never imagined happening.

I graduated [from high school] in 2010. And when I graduated, I thought that I would never be able to go to college. I remember walking across the graduation stage and just thinking to myself, you know, this is it, when I walk off stage, there’s no more opportunities, there’s nothing for me, there’s nothing whatsoever. I knew that other students felt the same, and I wanted to be able to help them.

How did the election affect you?

DACA has given me many things. I’ve been able to work, I’ve been able to drive, I’ve been able to go to one of the best schools in the country. But it also gave me a false sense of security. And I didn’t realize how fragile that sense of security was until after the election. I had gotten so used to deferred action that there were times when I had forgotten what my life was without it. But that all changed with the election. Watching the news come in, I remember feeling for the first time that my sense of safety had been threatened.

You decided it was unsafe to study abroad after the election. How did that feel?

I remember talking to my friend and just getting really emotional, and at first I didn’t know why. But then I thought about it more and more, and the reason why I was getting so emotional wasn’t because I wasn’t going to be able to go to Cambridge, at the end of the day that’s a very small thing in the larger scope of things. But the reason why I was getting so upset was because when I was growing up, I felt that no matter how hard I worked, no matter how high my grades were, no matter how high people thought of me, the goal of going to college was unattainable no matter what I did. And in November I felt similarly.

That was the first time in maybe six years that I felt like it didn’t matter how hard I worked, it didn’t matter what I became, because at the end of the day it could all be taken away from me at any moment. And that was so hard honestly. I try not to focus on that so much as I focus on all the reasons to keep going.

‘I felt like somebody opened the door and I could fly out and be free. ‘

Gabby Pacheco

When DACA was announced, Maria Gabriela Pacheco says she felt like someone had opened the door of what she calls the “golden cage” of America, allowing her to fly free for the first time. By 2012, she was already a nationally recognized immigrant-rights advocate, having helped push the Obama administration to consider enacting DACA in the first place and leading an immigrant-rights walk from Miami to D.C. with three other undocumented students. In 2013, Pacheco became the first undocumented Latina to testify before Congress. Through DACA, she was able to return to Ecuador for the first time in 23 years to visit her grandmother before she passed away. She also bought a car and a farm in Miami, where she currently lives.

Though she was able to obtain a green card, Pacheco is still entrenched in the fight for immigrant rights as the program director at TheDream.us.

After DACA was signed, what was the immediate impact on your life? How did your life change?

As soon as DACA was announced, I felt like somebody opened the door and I could fly out and be free.

In my personal life, in 2011 I had gotten married but had spent my time living in D.C. So that also gave me the opportunity to move back down to Miami. Then in 2013 I received my DACA. I got a driver’s license, and I started driving again. In 2014, I think, I bought a car. It wasn’t my dream car, but it was definitely a car that I really liked. It’s a Mercedes SUV, a small one. It was used. I couldn’t afford a brand new one, but it doesn’t matter.

If it wasnt for DACA, I wouldn’t have been able to travel back to Ecuador for the first time in 23 years. [My grandmother] was on her death bed, but I did get to see her right before her passing. And so I wouldn’t have been able to do that if I didn’t have DACA. I think about that all the time. I just wish I was able to give that opportunity to my mom, who is undocumented, and my sister, who was too old for the DACA program.

One of the biggest and most significant things I was able to do with DACA was buy a house. Last year in April I moved into my little farm that I bought here in Miami. I have chickens. I sometimes let my neighbor’s horse come and graze on the grass. We have now three dogs and a cat. We’re trying to slow the pace because a lot of people are like, “you have space in your house, would you mind sheltering this dog?” So we’ve adopted many dogs since we got the house.

How did you react to the 2016 presidential election?

Last year I started forcing myself to take care of myself. DACA afforded me an opportunity to have a job, to have health insurance, and having insurance was really important for me, especially last year because going through the routines of getting checked I was diagnosed with cancer. I was able to go through treatment, but after the election I was really, really afraid. I was afraid thinking that I was going to lose DACA. And if I was going to lose DACA, I was also going to lose my job that gave me health insurance. I thought, “how am I going to afford the treatments, the medication?” So that was really, really difficult for me during that time. Thankfully this year in February, we found out that the treatment had worked and the test came back negative for cancer.

I wrote a post on Facebook that later went viral and a couple of news people picked it up and shared it. Right after the election, I had not shared publicly that I was going through a cancer ordeal. I couldn’t sleep just thinking about it. I wrote a preparation plan on what I needed to do in case DACA was rescinded. It included practical things, but things that you wouldn’t think about doing, like getting a three month’s supply of medicines I need. I started building a plan of what I would do if DACA goes away. Thankfully, my husband last year became a citizen and filed a request for me to become a green card holder. In May I went in for my interview and have obtained my green card.

What message do you have for other undocumented folks? For other Dreamers who may be concerned?

The United States’ future depends on making sure that young people that have DACA are prepared to continue to help the economic health of this country. As much as DACA changed my life, I also know what it is to live without DACA. I know what it is to live as undocumented. I know what it’s like to pay as an international student to get my tuition. I was able to get relatively good jobs. I was able to live a good life. I think it’s important for the younger generations to know that the world will not end. We are a resilient community and we’re going to be okay.

These photographs were originally taken for the June 25, 2012 cover story of TIME. Alana Abramson contributed to this report.

Correction: A prior version of this story misstated the nature of Tania Chairez’s work with DACA students in Colorado. She works with KIPP Colorado Schools to help DACA students; she does not handle the state’s entire DACA caseload. The original version of this story missppelled the last name of one of the Dreamers. She is Daniela Bravo-Terkia, not Bravo-Turkia.