An underwater investigation of coral bleaching in the South Pacific

By Justin Worland | Photographs by XL Catlin Seaview Survey

Richard Vevers has traveled the globe to photograph coral reefs since quitting his advertising job. In 2011 he cofounded the XL Catlin Seaview Survey, a collaboration between the University of Queensland and a number of research institutions, photographing underwater corals as they adapt to climate change. He captured the Great Barrier Reef during its latest—and most devastating—mass die-off, and documented how coral off the coast of Belize had partially recovered thanks to a no-fishing zone.

But no dive has stunned Vevers as much as the sight of corals going white during an early March dive in the New Caledonia Barrier Reef, located about 1,000 miles from Australia’s better-known Great Barrier Reef.

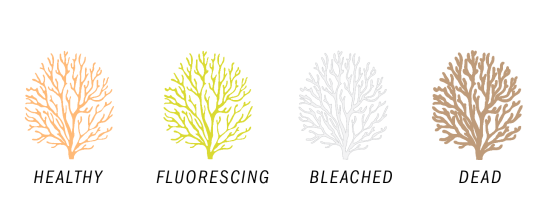

Coral die-offs—caused by a process known as bleaching—tend to look as bland and lifeless, in contrast to the vibrant rainbow colors of thriving coral. Bleached coral reefs usually appear as an endless stretch of white coral and eventually turn to dead brown coral. But in New Caledonia Vevers found something different.

The corals he captures lit up fluorescently as their color left them slowly but surely. The crew captured the moment using their underwater SVX camera system—a technology that captures 360-degree imagery underwater. “In the past people simply haven’t gone to the right location at the right time,” says Vevers. “I was blown away… I’ve never seen something so beautiful, but it’s dying.”

on your phone? Click “360” then move

The bleaching in New Caledonia represents just a small fraction of the total bleaching that has occurred across the globe since 2014. The ongoing bleaching event is the worst ever, with reefs affected from Florida to Australia, according to a report from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). It’s also the longest bleaching event in recorded history, and scientists say it shows no evidence of ending any time soon. With the Our Ocean conference scheduled to start today in Washington, there’s no better time to focus on one of the biggest threats to aquatic health.

A number of factors—from water pollution to disease—can irritate corals, causing them to expel the colored algae known as zooxanthellae that they live with symbiotically. Warm water temperatures caused by a combination of long-term climate change and short-lived weather phenomena like El Niño deserve the blame for the current bleaching episode.

Last year beat out 2014 as the warmest year on record and 2016 is on track to be even hotter. On top of that, sea surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific rose by more than 2°C (3.6°F) during the latest occurrence of the El Niño climate phenomenon. It only takes a sustained water temperature spike of 1°C (1.8°F) above average to upset corals and lead to bleaching.

“Rather than just being a single event tied to a single El Niño there has been continual bleaching in the Pacific,” says Mark Eakin, a NOAA coral reef scientist. “It’s unlike anything we’ve ever seen before.”

The corals in the New Caledonia Barrier Reef have been lucky by most measures—a drop in local temperatures has allowed many of them to recover. But corals in other locations haven’t been so fortunate. A recent survey of some areas of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef suggested that more than a third of the corals in the region might have died, leaving a marine graveyard behind.

“The soft corals were just decomposing—animals literally dripping off the rocks,” says Vevers of his dive in the Great Barrier Reef. “The most horrifying part was that we just absolutely stank of rotting animals. That’s when you really realize that reefs are made up of billions of animals.”

A full global accounting of how many corals have survived the latest bleaching episode will take months, if not longer, but coral scientists expect the worst. The consequences of losing coral reefs are catastrophic for the oceans. There’s a reason scientists describe reefs as the rainforests of the sea.

Reefs occupy just 1% of the world’s marine environment, but they provide a home to a quarter of marine species—including a unique set of fish, turtles and algae. Many of these species could be lost permanently, but with temperatures only expected to rise in the coming decades chances are slim that reefs will be able to rebuild from scratch.

“You can’t grow back a 500-year old coral in 15 years,” says Eakin. “In many cases, it’s like you’ve killed the giant redwoods.”

The death of coral also represents a huge loss—as much as $375 billion annually—for the local economies along the globe they support. Reefs support local tourism and the commercial fishing industry. They also protect coastlines from flooding during extreme storms.

Perhaps the most concerning aspect of coral loss is what it suggests about the future. The fragile nature of coral reefs leaves them hypersensitive to climate change, but ecosystems above ground and beneath the ocean will also be vulnerable to rising temperatures in the coming years and decades. And while humans can still stave off the worst effects of climate change, some level of warming remains inevitable.

“If you think of corals as canaries [in a coal mine], they’re chirping really loudly right now,” said Jennifer Koss, NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program director, at a recent press conference. “The ones that are still alive, that is.”

Graphic sources: World Resources Institute; XL Catlin Seaview Survey; NOAA

Animation by Heather Jones for TIME