Last of the Colombian Cowboys

The Llanero tradition is rooted in five centuries of culture

Photographs by JUANITA ESCOBAR

Text and edit by ALEXANDRA GENOVA

The life of a Llanero – or Colombian Cowboy – is tough. The six-month winters that plague the dramatic plains means rain almost every day; the hardy men must ride their horses through overflowing rivers, teeming with insects and fish, away from the floods to dry land. Summers bring a feverous, muggy heat, unbearable for the average human or pedestrian horse. But the Llanero’s arduous, semi-nomadic existence is rooted in five centuries of wisdom and succeeds because of a deep respect for the land they have conquered.

It was this soulful stoicism that first caught the imagination of photographer Juanita Escobar. She travelled to the region aged 19 to document the spectacular mix of wildlife, flora and fauna for the Natural Reserve Palmarito in the Casanare State. But during her work, a chance encounter would change her path and purpose.

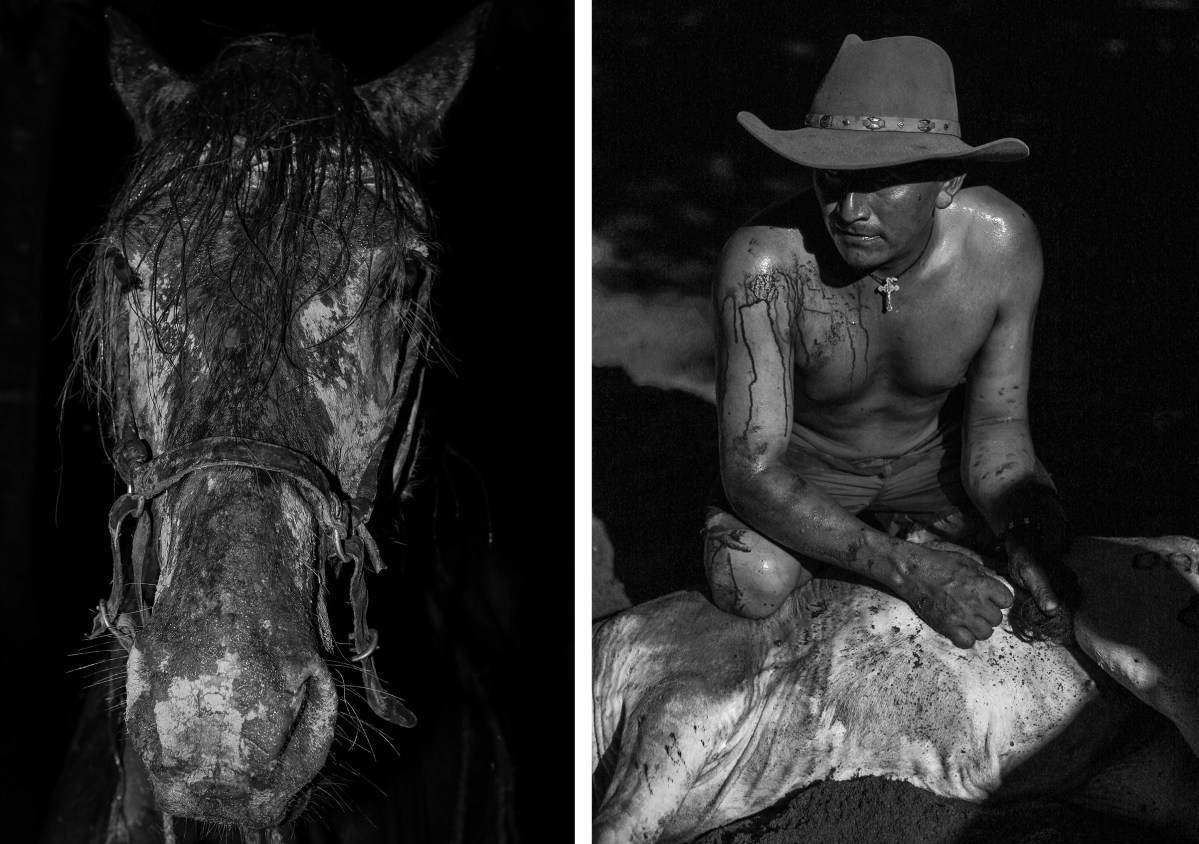

(L) The horse named Chemerejure. Hato Santana, Casanare State, Orinoco Plains, 2015. (R) Parrandero, a Llanero from a village called Quebrada Seca. Hato San Pablo, Casanare State, 2009.

Escobar met a 65-year-old Llanero, named Ricardo Daza, who invited her to join him and document the Llanero way of life; unique to that region and unfamiliar to the average Colombian. “He was so excited because I was a photographer and he wanted to show me his culture,” Escobar tells TIME.

She joined them – caught up in the heady romance of life on the theatrical landscape – and didn’t leave for seven years. Not only did she document daily life, she lived and breathed it. In that expanse of time, friends died, babies were born, hearts were broken; she was there and their stories became her own. The Llanero, so-called after the Llano, which describes the grasslands occupying western Venezuela and eastern Colombia, became her photographic focus and her spiritual purpose.

Ximena tries on her mother’s wedding dress. She feels the unease of a young woman who wants to get married but not lose her freedom. Savannahs of San Luis de Palenque, Casanare State, 2015.

“I was 20 years old, so I decided to explore my way to approach documentary photography through this culture and through this process of life,” she says.

Escobar was drawn to their passion but quickly learnt their harsh reality. “It is not so romantic. And after one week, you realize that you are sick. You are sick because it’s so alive, all the territory,” she says. “It’s not like the Gauchos [Argentinian Cowboys] who have a lot of clothes because of the weather. Here in Venezuela and Colombia they don’t wear shoes. Never.”

It was a steep learning curve. First, Llanero Daza taught her how to ride a horse and in doing so, taught her how to feel the rhythm of their culture. On her first ride, she joined 40 Llaneros from 4am to 7pm as they crossed the plains herding cattle. She was given two horses, and the first, named Chemerejure, is the subject of a particularly fiery portrait (see above). “They say that we resemble our horses or they resemble us,” says Escobar. “It is a picture of what we have lived together, of what we became together.”

Llaneros capture wild cattle at dusk. The legs are tied and they are left in the field until the next day, when they can be cared for by daylight. Hato Santana, Casanare State, 2015.

Shirley Guarín resting at her parent’s home. Orocué, Casanare State, 2015.

The Llanero’s sense of purpose is closely tied to a deep connection to their horses. “The horse is the vehicle, it’s the center of their culture,” says Escobar. “The way to approach love, the way to approach death – it all comes from the horse.” Learning to live with the horse in this way, transformed her. It became the symbol of a life with few possessions but many companions.

The importance of land is also keenly felt in Escobar’s pictures. From the raging, oppressive clouds to the grey, tilting horizon; the drama of the sky and land is a character in itself. “The Llanero belong to the territory,” says Escobar. “They are semi-nomadic. Their roots come from indigenous people so they have a really close knowledge of the plants, of the ways to heal. They need the territory to survive but they are also its caretakers. I think the waters, the rivers and the animals can express themselves through the people who are living there.”

There are two seasons in the Colombian plains: 6 months winter and 6 months summer. The difference is not in temperature but in the amount of rain. Vichada state, 2015.

A Llanero shares a companion’s horse after his own horse grew overtired during the Trabajos del Llano. Santana Ranch Savannahs , Casanare State, 2015.

When Escobar started out, her process sought a historical truth. She began by focusing on the distinctly unequal role of women within the Llanero culture. She worked with anthropologist, Francisca Reyes, to document their hopes and dreams, their sexuality, their frustrations and their ambitions. “In the first four years the most important thing was to build character and build a testimony,” she says.

Next, she focused on the Llanero’s poetry and musical culture. “It’s one of the richest musical cultures in Colombia and in South America. It’s really attached to their work; they are always singing and composing and playing music,” says Escobar. Again, her purpose was didactic and she kept a distance from her subjects.

Summer time. The dust floods the working corrals and the Savannah, which is flooded during winter. Hato Santana Savannahs, Casanare State, 2015.

Angel Marrero, working with the cattle in the corrals of the Matenovillos ranch, during the Trabajos del Llano in summer. Matenovillos Ranch, Casanare State, 2009.

But as her relationships deepened, her photography shifted into something more visceral. “At first I didn’t use a flash because I wanted to be respectful of the people. But then I decided that I don’t want to be respectful anymore,” she says. “I want to explore this intimacy and express myself.” The results are at once powerful and vulnerable; nakedly raw and hypnotically intuitive.

Though the work is intensely personal, it also speaks more broadly to the Llaneros as a culture at risk. “By depending completely on the territory to exercise their cultural practices, they enter into a risk situation when those territories are more and more colonized physically and culturally by industries like oil or palm tree oil or rice. Each day there are fewer corners where the culture and the basis of the daily activity can be kept alive.”

(L) Mosquito net at the Guarín family home. Orocué, 2015. (R) Wendy Ramirez plays with her brothers in a pond in the savannah during winter. Matabrava Ranch, Casanare State, 2015.

Added to that, the Peace Deal – signed by the FARC and the Colombian Congress in November 2016 – though mostly positive, means that the Amazonia and Orinoco region will no longer be protected in the same way, says Escobar. “The territories, the people – including the nomadic Indians – and the biodiversity are all in danger,” she adds.

Escobar believes the way to preserve the Llanero’s dignity and territory is to present what she has lived and learnt as a photographic record. The eight years in total that she has dedicated to the Llaneros will now culminate in a monograph, titled Llano. The book, which has no text, is a testimony to the journey of discovery, to light and darkness and to a proud culture that could soon fade away. “I learnt the simplicity to live really closely to the observation of the landscape, which is not simple at all really,” she says. “It’s a huge knowledge that you have to re-learn. It’s like being re-born.”

Oni Ramirez pulling a horse (attached to her horse’s tail) that will be ridden for the first time during the Trabajo de Llano. Santana Ranch, Casanare State, 2015.

Juanita Escobar is a self-taught documentary photographer from Colombia. Follow her on Instagram. Her book, Llano, is being published by independent Latin American Publishing House KWY and edited by Musuk Nolte, with the help of crowdfunding – due to be completed in July. Help make the book come to life by donating here.

Alexandra Genova is a writer and contributor for TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.