His unlikely crusade became a genuine campaign. Now Sanders faces a choice—and a test

Bernie Sanders wanted to sit in the sun, but not even the sharp California rays on the rooftop deck at a San Diego hotel could brighten his mood. There was still too much at stake, he said, too many lies being told, too many foes with bad motives inside his adopted party. The irascible impatience that has defined Sanders’ entire life—the fury of David against Goliath, of the worker against the owner—was peaking. And still people were telling him to hang it up, get in line and go back to the dairy pastures of Vermont.

“They wanted to end this thing before the first ballot was cast. That is totally absurd,” he said. “It is clearly undemocratic. It is a tool for the Establishment to push its candidate forward.” By Establishment, Sanders means the Democratic Party, a group he joined last year only to become one of its dominant personalities, winning 20 states and territories.

By candidate, he means Hillary Clinton, the rival who will almost certainly become the Democratic nominee in Philadelphia in July. And that’s because she has won 3 million more votes than Sanders, because she has won 271 more delegates than he and because nearly 75% of the party elite, who can cast their ballots at the convention for whomever they want, are not only against him but increasingly terrified that his continued defiance will help elect Donald Trump to the presidency.

Squinting in the sunshine, Sanders issued a long list of complaints. “The corporate media is incapable of covering a national campaign in a serious way,” he said, firing a shot at his interrogator. The Clintons, he continued, “play very dirty.” Hillary’s attacks on him had been “outrageous,” courtesy of her super PAC helmed by “the scum of the earth.” The chair of the Democratic Party had “stacked” the deck against him. “What people don’t appreciate is that in every state we have participated in—that’s 44 states up to now—we have taken on the Democratic establishment,” he said.

As the primary campaign comes to an end, Sanders faces a choice and a test. He could urge his supporters—many newcomers to politics—to join up with the broader party to help Clinton defeat Trump. Or he could shift his insurgency into a full revolt in a final effort to remake the party in his progressive image, moderates be damned. For the moment, he has made his decision. He will mount a “messy”—his word—fight at the convention in the name of redefining the party and becoming its nominee. He will argue for changes to the way the party chooses its nominees and even bigger changes to its dogma, including a $15 minimum wage, free college tuition at public schools, tax hikes on the wealthy, government-funded health coverage and paid family leave. If he doesn’t get his way, his supporters might ditch the party.

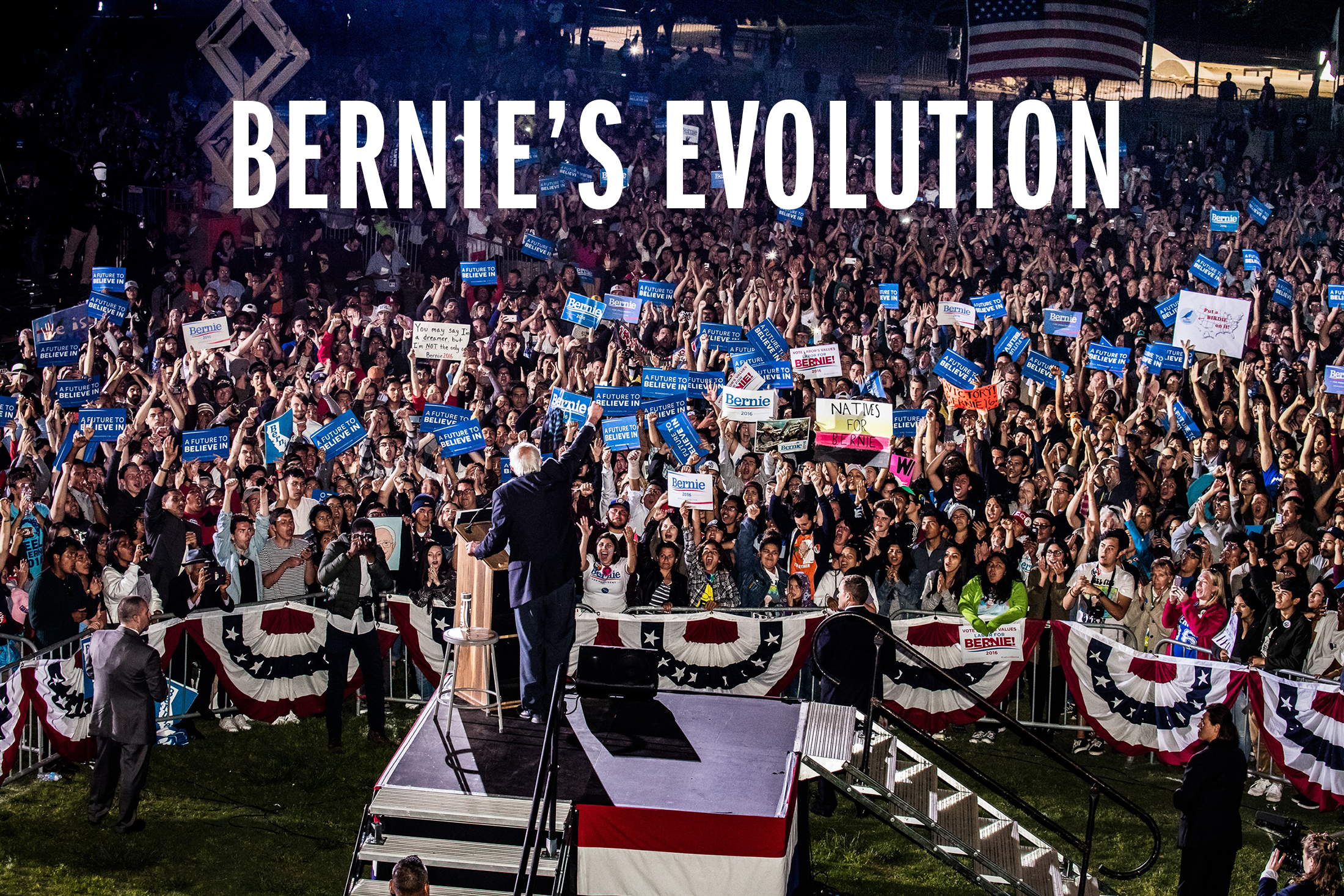

At a rally in nearby Irvine, the heart of once solidly Republican Orange County, a raucous crowd of more than 10,000 broke into another “Bernie or bust!” chant. “Never Hillary!” onlookers shouted as he took the stage. Then “F-ck Hillary!” came from the crowd. It’s the sound of a revolution, but not just the one Sanders is leading: an NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll released on May 23 found that roughly a third of Sanders supporters would not switch their allegiance to Clinton in a matchup between her and Trump. “The more you learn about Hillary, the more you’re, like, ‘God, she’s a monster,’” said Amber Churchill, a 33-year-old server at the Cheesecake Factory who attended the rally. “I’m at this point where I’m just, like, Burn the place down.”

Which means, sooner or later, Clinton and the Democratic Party will have to try and make peace with the 74-year-old democratic socialist from New York City via Burlington, Vt. When Sanders launched his national campaign, he was a curiosity, one of two independent Senators. He wandered the halls around his D.C. office largely ignored, even after he announced he was running. Sanders didn’t expect to win; he wanted to make some points and push a progressive agenda. If he were planning on running a traditional campaign, he would have rented bigger headquarters. Longtime Sanders aides assured reporters and donors that their boss would never run a negative ad against Clinton.

Besides, the pair had something of an intellectual rapport. In a photo signed “Hillary Rodham Clinton, 1993,” she wrote to Sanders, “Thanks for your commitment to real healthcare access for all Americans.” Television footage showed Sanders standing directly over Clinton’s left shoulder as she spoke on the topic at Dartmouth College. Even after their campaigns started going in different directions last year, they remained amiable. They ran into each other in the Amtrak Acela waiting room in New York City’s Penn Station in June. “Bernie!” Clinton shouted across the room as he walked over to greet her. Sanders said quietly to an aide as they walked away, “Maybe I shouldn’t say this, but I like her.”

Things began to simmer over the summer as Sanders’ crowds grew. He drew more than 5,000 supporters in Denver; 10,000 in Madison, Wis.; and 28,000 in Portland, Ore. Few people, including Sanders, had foreseen this, but he soon sensed that he had tapped into a groundswell of discontent that might take him somewhere. His hour-long speeches, scrawled by hand on a yellow legal pad, grew more ambitious and promised a movement to come. By the time he could see his breath at outdoor campaign events, he thought he stood a chance to actually win some states.

If Sanders had promised never to go negative, no Clinton had ever done so. The hammer fell during the first debate in October. When a moderator asked Clinton if Sanders had a tough enough record on guns, she pounced. “No, not at all,” Clinton said of her rival, who represents a mostly rural state. Months later, Sanders still smarts over the constant attacks about guns.“The idea that I am being called a tool of the NRA, a supporter of the NRA, is really quite outrageous,” he says.

Soon the hits from Clinton’s boosters were relentless. Sanders’ aides expected them, but the candidate’s shock at the Clintons’ hard-nosed politics was unmistakable. The tactics went against his hopes for a high-minded campaign fought on issues, not on microfiche or her email practices. And as Sanders’ crowds grew, so did his poll numbers and contributions from small donors. And so did the Clinton attacks.

Meanwhile, Sanders sensed a finger on the scale. Party chair Debbie Wasserman Schultz, a Florida Congresswoman, scheduled just a handful of debates, during off-hours and on weekends, a light schedule that favored Clinton, who feared gaffes that could be used against her later. She orchestrated a joint fundraising committee of the DNC, state parties and the Clinton campaign, a standard arrangement but one Sanders suspected was being used to channel small-dollar donations to the Clinton campaign. Then in mid-December, Sanders got a direct call from Wasserman Schultz.

She was cutting off the Sanders campaign from an all-important voter database, housed at party headquarters, because several Sanders staffers had been caught accessing Clinton’s data. Sanders and his inner circle were furious—more so at the DNC, it seemed, than at the aides who put in jeopardy millions of dollars of data. Within hours, Sanders campaign manager Jeff Weaver was on a constant loop on cable saying the Democratic Party was trying to undermine the campaign. “Nobody debates that the entire DNC is supportive of Secretary Clinton,” Sanders says today. He has since helped raise almost $300,000 to support Wasserman Schultz’s primary opponent.

Perhaps the only person more surprised than Clinton by Sanders’ early win was Sanders himself. After fighting to a draw in the Iowa caucuses, he couldn’t stop smiling as he zoomed in the early-morning hours from Des Moines to Manchester aboard a rented jet packed with journalists finally taking him seriously. In New Hampshire, Sanders started to receive Secret Service protection and massive press coverage of his message. A landslide win over Clinton followed. It was a stunning turnaround for someone who just months earlier found himself sitting in the Manchester airport by the liquor store at Gate 8 in anonymity, waiting for a delayed commercial flight. And as often happens in politics at such moments, expectations began to exceed reality: for Sanders and his dogged staff, it seemed increasingly likely that they might be on a road to victory. He had briefly forgotten the Clintons’ appetite for a political brawl.

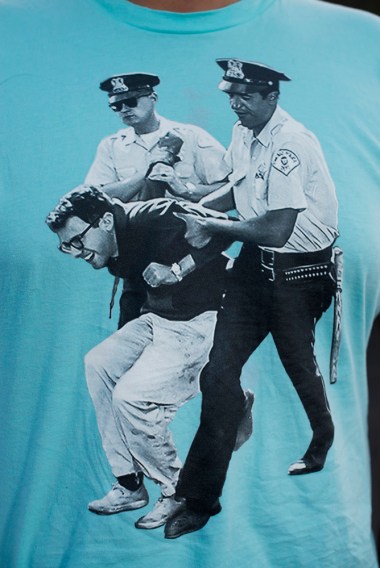

In fact, the Clinton machine was just warming up. Clinton researchers had spent months digging into Sanders’ vulnerabilities—standard operating procedure for any modern campaign—and countless outside allies offered their binders of research too. There was plenty to go around: he was once ambivalent about South American socialist dictatorships, he honeymooned in the Soviet Union, he voted against the Wall Street bailout that ultimately helped U.S. autoworkers and he had been critical of Barack Obama’s first term. Clinton tagged Sanders for being AWOL during the fight for health care in 1993 and ’94, despite plenty of TV footage and photography to the contrary. Fair or not, the onslaught left Sanders upset; he had never faced this kind of scrutiny. “We know a lot of stuff has been leaked into the papers which are lies and distortions,” Sanders says. “Their response is, ‘Look, that’s the world we live in, that’s what you gotta do.’ I understand that. I don’t think that’s what you gotta do.”

Goaded by his insular, mostly male circle of advisers, Sanders lashed back, questioning Clinton’s integrity and railing against her speaking fees from big corporations and Wall Street firms like Goldman Sachs. “He got into a space where he felt comfortable pushing back,” says an adviser. “People get into a corner and they strike back very hard.” The cordial chitchat between their aides in the post-debate spin rooms stopped or turned confrontational, with Clinton adviser Karen Finney and former NAACP president Benjamin Jealous, a Sanders ally, clashing in open view of reporters after one forum in Flint, Mich.

By spring, the candidates had stopped calling each other to offer congratulations on victories. Backstage at a campaign event in early April, an aide showed Sanders a headline in the Washington Post: “Clinton questions whether Sanders is qualified to be president.” Without reading the story, Sanders scribbled on his legal pad and angrily charged onto the stage at a Philadelphia event, saying “the American people might want to wonder about your qualifications, Madame Secretary!” Of all the arguments to make against Clinton, unqualified was perhaps not the strongest.

None of this was happening in a vacuum. Voters were paying attention, and in a year that favored outsiders over insiders, many cheered on Sanders, who chops his own wood for his stove and has never worn a tuxedo, even after 25 years in Washington. By West Virginia’s May 10 primary, exit polls showed as many as a third of Sanders supporters were saying that, to deliver the revolution their man was demanding, they would rather vote for Trump than Clinton.

Soon all parties were feeling aggrieved. Clinton’s team in Brooklyn, now expanded to two floors of a nondescript office building with views of the Manhattan skyline, remained close. Wins were accompanied by dance parties. Losses came with assurances that the setbacks were not enough to deny them the nomination. Clinton aides, who from the start expected their boss to be the nominee, found themselves starting to despise Sanders and his unwillingness to stand aside to let the first woman lead a major party’s ticket. In office rentals in downtown Burlington, meanwhile, Sanders’ team internalized the lack of respect from the Clinton camp, especially the people they saw on television talking about how he needed to go away. “No one (in 2008) ever said Clinton needed to drop out, even after the math no longer worked,” one Sanders adviser said. “Now, it’s all we hear.”

On May 14 on the Las Vegas Strip, the frustration turned to rage. Sanders’ supporters petitioned to change the rules at a state party meeting, then attempted to rush the stage when they didn’t get their way. The arcane party rules left many of Sanders’ first-time activists confused and convinced they had been wronged. Nevada Democratic Party chairwoman Roberta Lange got death threats. “Someone said they wanted to blow my face off,” Lange says, adding that she received voice mail about “being hung in a public execution.” She even got a threatening text message from someone claiming to know where her grandson goes to school. Sanders condemned the chaos in Nevada but said he shared supporters’ frustrations. His allies, at first, didn’t believe what was happening. They had successfully rallied like-minded activists—many of them new to politics—who believed the little guy was getting screwed. There’s no telling if they will come back and try politics again.

That Risk Makes clinton wary of angering Sanders or his disheartened supporters. She and her advisers know they must give Sanders something he can count as a win, lest they lose to Trump. Clinton’s closest advisers have promised him an open ear and a seat at the table in Philadelphia. “Let’s all remember, there is far more that unites us than divides us,” Clinton spokesman Jesse Ferguson said in a statement to TIME for this article. Sanders “has been able to tap into real concerns among progressives,” says Neera Tanden, a Clinton ally who will help negotiate the party platform in July.

If Sanders’ advocates work toward a positive agenda, she adds, “he can have an incredible amount of say in the future of the Democratic Party.” He may want an even bigger job, one that involves a party-paid plane and an official role in helping take back the House and Senate in the fall. That would give him the credentials he needs to crisscross the nation, giving speeches and keep growing the movement. Clinton and her team are likely to balk at all of that. And if Sanders comes away empty-handed, more than the White House is at stake. A left-center split in the Democratic Party will unfold, and where that leads no one knows.

But it is unlikely that Sanders would remain as spiritual leader. When the Republican right emerged from the mainstream GOP in the form of the Tea Party in 2009, no one imagined the party would turn to Trump as its standard bearer. So what happens next is largely up to Sanders. “This is a matter of Bernie switching gears, which is very hard to do, and I had to do it,” says former governor Howard Dean, who conceded the 2004 Democratic nomination to John Kerry only after many party elders interceded. “You can be aggrieved if you want, but then you end up as Ralph Nader.” Sanders will either seek a compromise, likely losing on most of the issues that matter to him, or he can try to force his agenda through a chain of dissenting votes that could further divide the party in a bitter drama played out on national TV. Either way, Clinton has shown little sympathy for his demands.

“We got to the end in June, and I did not put down conditions,” she said of her race against Obama in 2008. If things don’t go in Sanders’ favor, his allies have prepared for him to show his force. The City of Philadelphia has issued permits for four days of protests directly across the street from the main convention venue. As many as 30,000 protesters will be allowed to assemble within earshot of the arena. They will gather in a park named for FDR, which offers a small dose of historical irony. Roosevelt won his party’s nomination in 1932 in Chicago only after delegates cast four rounds of ballots.

Correction: The original version of this story misstated the number of U.S. Senators who are independents. There are two.