By Alice Park

Eat less sugar. It’s really a no-brainer. The obesity epidemic now encompasses two-thirds of the American population, including a third of children, so any opportunity parents have to cut calories seems like a good idea. And one of the first targets has to be sugar. Especially now that there are so many low-calorie options made using with artificial sweeteners: sugar free gum, sugar free drinks, sugar free ice cream. Kids can have their cake and eat it and then have a diet soda afterwards.

But these sugar-substitutes may not be the good-for-us wonders that they’re touted to be.

While the calorie savings are certainly real, some experts are beginning to doubt whether the compounds end up doing what they’re intended to do. Consuming fewer calories should help us stay slim and lose weight, and because they aren’t sugar, these stand-ins are also supposed to protect us from getting the sugar spikes after meals and lower the risk of diabetes.

But there’s some data that suggest artificial sweetener users don’t always lose weight, and that they may not be armed against diabetes. The body reacts to artificial sweeteners differently than it does to sugar — the healthy bacteria that live in the gut, for example, change when these compounds are around — and the consequences might be both surprising and unwelcome, especially for children.

Here are the challenges and questions being raised about sugar substitutes, and the best advice from experts on whether it’s worth using them or not.

Switching to artificial sweeteners won’t (necessarily) help children lose weight

While studies show that sugar substitutes can lead to weight loss, the number of pounds shed is not the dramatic drop that most diet soda drinkers, for example, probably think they’re getting. Yes, a diet soda is a better choice for a child than a sugar-sweetened one, but it’s not as conducive to weight loss as switching to water or even milk.

The reason is that nobody lives on diet soda alone. To understand how artificial sweeteners are affecting weight, you have to consider everything else that a child eats — which most likely contains a lot of sugar as well as sugar substitutes. So the effect of removing the sugar calories on children’s weight ends up being a function of those kids’ behavior and their biology.

For one, kids who eat a lot of sugar often consume it as part of a pattern of overeating in general. It’s just another thing they eat too much of. So when they switch to diet soda they’re still consuming enough calories from other foods that they don’t drop any pounds. Simply cutting down on one source of sugar may not be enough to affect their weight in a significant way.

The biological effect is more complicated, and contributes to a lot of confusion about why, if low- or no-calorie substitutes are so ubiquitous, we still have an obesity epidemic among kids. Animal studies hint that fooling the body with sweet taste but no calories might actually lead to more obesity and diabetes, the very conditions the compounds are supposed to prevent.

Here’s how it works: taste receptors on the tongue detect sweetness, and alert the brain that calories are on their way. The brain then sends signals to the pancreas to prepare release of insulin, which sops up and breaks down the sugar and sends it to cells like muscles that need them for energy, and stores the rest as fat for later use. But if the whole system is activated by the sweet taste of artificial sweeteners, then isn’t followed up with actual calories in the form of sugar, what happens?

“Does the pancreas go, ‘Man, I was waiting for the sugar but now I’ll wait until tomorrow,’ or does it go, ‘The insulin is ready to go so I’m going to find calories to work on?’” asks Dr. Robert Lustig, professor of pediatrics and director of the weight assessment for teen and child health at University of California San Francisco. “We don’t know yet.”

There are hints, however. In a small study involving 17 morbidly obese adults, researchers measured how quickly their bodies broke down glucose both after drinking water and drinking a diet soda. Given that the diet soda’s sweetener contained no calories, the scientists expected both tests to show the same amount of insulin response. But after drinking the diet soda, the volunteers showed a 20% increase in the amount of insulin their bodies released than after they drank water. Continued over-production of insulin can lead to insulin resistance, in which the body’s insulin no longer responds appropriately to glucose, and can prime the system for diabetes.

Another small study, this one involving a dozen healthy women of normal weight, also hinted that the brain may see sugar substitutes differently in a very important area—appetite regulation. Researchers scanned the brains of the women after they downed a sugar solution and after a sucralose solution. The area of the brain that senses when enough calories have come in lit up after the women drank the sugar-based solution, but not after the sucralose one. It’s not clear whether that actually affected how much the women would eat, but it suggests that the brain—and therefore the body—does not react the same way to sugar and artificial sweeteners.

Still, other studies hint that perhaps this effect, even if it’s significant, may not be very strong. Richard Mattes, professor of nutrition science at Purdue University, notes that people with taste disorders, in which everything tastes sweet, seem to maintain normal weight, and aren’t necessarily heavier than people with properly functioning taste receptors.

In animals, there’s stronger evidence that fooling the body with no-calorie sweeteners could be setting the animals up for the disease. Mice that have been fed artificial sweeteners tend to overeat, for example, and gain weight within two weeks. That might be the same in people, although studies are still being conducted on this. Normally, when the body breaks down calories from food, it regulates how much is enough, and when sufficient amounts are stored, the digestive system sends signals to the brain that say ‘We can stop now.’

But if the calories don’t arrive after the sweet taste activation by artificial sweeteners, and yet do arrive when the child goes on to eat something with real sugar, then it’s possible the system gets confused and can no longer accurately read when the sweet taste signals calories coming in, and when it doesn’t.

The rats and mice fed artificial sweeteners also show lower amounts of a peptide that regulates blood sugar levels, and signals the stomach to empty its contents after nutrients and energy have been absorbed. With less of the peptide, the stomach empties more quickly, which could also lead to more feelings of hunger and prompt the animals to eat more.

The bottom line, says Kristina Rother, chief of the section on pediatric diabetes and metabolism at the National Institute of Health’s (NIH) National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, is that artificial sweeteners mess up the body’s exquisitely balanced system for taking in calories, using them for energy, and squirreling away enough for just-in-case purposes. “It’s Pavlovian,” she says. Just as when dogs heard the bell and knew that meant food was arriving, in these studies the animals are tasting sweetness and then getting calories. “But now we’re confusing the dog, and just ringing the bell by just letting them taste sweetness without the calories. What happens is that animals’ systems say ‘Who cares?’” They can no longer rely on the sweet signal to herald calories, so they no longer distinguish between hungry and not hungry and eat whenever and whatever they want, leading to weight gain. “[Artificial sweeteners] are fooling the body, and once it’s fooled enough, it’s just not going to respond any more,” she says.

As it turns out, it’s not just animals that are not aware when they’re taking in artificial sweeteners. Humans can be unaware as well. To find out why, it’s useful to know the history of our search for a guilt-free sweet tooth.

Why you won’t find artificial sweeteners on food labels

Artificial sweeteners, some of which are synthetic and some of which come from natural sources like plants, were initially a boon for a very specific population of people—those with diabetes. Because diabetics can’t produce enough insulin to break down the sugar in their diet, glucose can accumulate in the blood and start to damage organs including the kidneys and the eyes. Having a compound that allowed diabetics to enjoy sweet-tasting foods without the spike in glucose was a gift.

The first such substitute, saccharin, was developed in the 1870s by researchers looking for coal tar derivatives—by coincidence, they discovered their byproducts were sweet. It didn’t take long for food makers to swarm to saccharin, since it was cheaper, sweeter and more reliable to make in the lab than sugar, which needed to be harvested and shipped. Other versions followed, and while some, like aspartame, contain about 4 calories per gram, others boasted fewer or no calories at all, making them a staple of the new diet-conscious culture that emerged in the 1950s and 1960s, and became a foundation of most weight loss efforts.

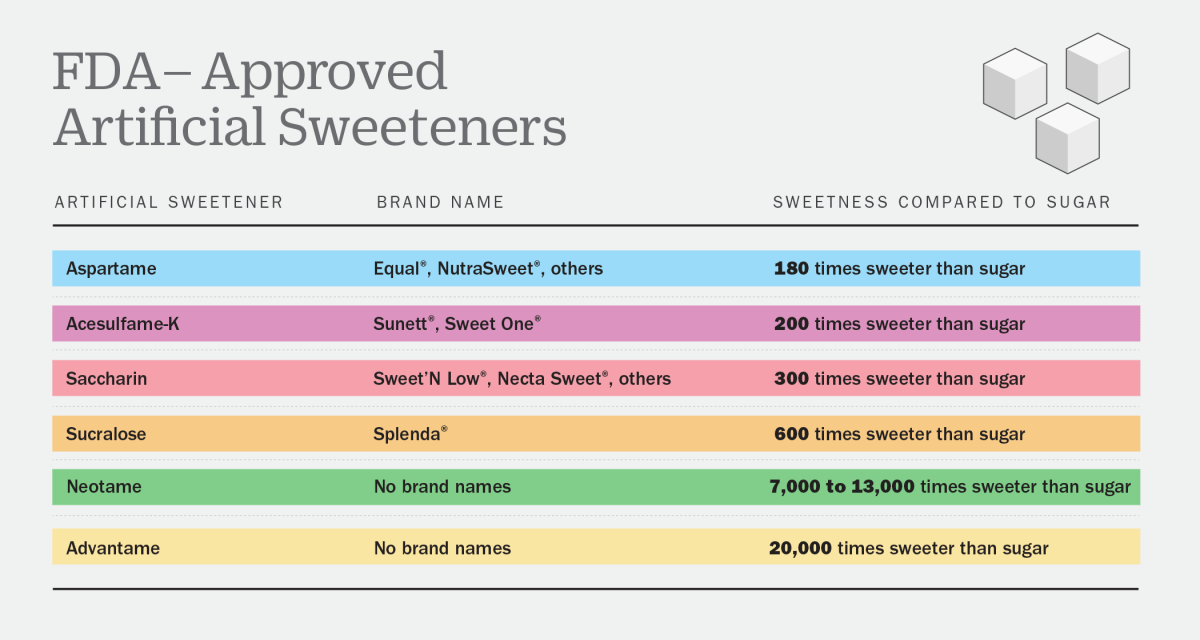

There are now six high-intensity sweeteners approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), increasingly sprinkled into a surprising number of foods on supermarket shelves, from diet sodas to frozen meals and savory snacks. Among more than 85,000 commonly purchased foods, 1% contain non-caloric sweeteners and 6% contain a combination of both sugar and non calorie sweeteners. Many parents don’t even know all the products that artificial sweeteners are in. Nearly half of waters (both plain and flavored) contain them, as well as more than a third of yogurts.

But to find them, you need higher order chemistry knowledge. Unlike fats, which are broken down into saturated, trans and cholesterol on nutrition labels, sugars are listed in one sweet lump, combining both naturally occurring forms such as sucrose (sugar cane), fructose (from fruit) and dextrose (from corn) as well as the lower calorie substitutes like aspartame, saccharin, sucralose (Splenda), stevia (Truvia), acesulfame potassium (Sunett, Sweet One, Ace K), neotame (Newtame) and advantame. To find the latter agents, you’ll have to hunt in the lengthy list of ingredients on the label.

“You can’t figure it out,” says Rother. She recently conducted an experiment outside a grocery store near the NIH in which she asked parents about whether they would buy foods with artificial sweeteners for their children. Most said no, but when told to select a few items from a table with popular packaged foods and drinks, most chose products with the sugar substitutes because they couldn’t identify them on the labels. “The amount of artificial sweeteners in products doesn’t have to be displayed,” she says. “In fact it’s never displayed.”

The FDA does, in fact, set limits for what it considers safe amounts of sugar substitutes that are food additives (naturally-based options only need to be shown to be ‘generally recognized as safe’). The limits range from 0.3 mg/kg body weight to 50 mg/kg per day for artificial sweeteners. So for a 50 lb. child, the average weight of a 6-year-old boy, that’s about 80% of a can of diet soda containing saccharin, or nearly six (!!!) cans of aspartame-containing soda a day. But the FDA can’t calibrate for things like metabolism and glucose levels and the way the body stores fat, since those studies are more challenging to conduct and to interpret. And that’s where some experts are getting concerned about sugar substitutes’ effect on the population.

So which is better for kids, sugar or artificial sweeteners?

There’s absolutely no question that artificial sweeteners contain fewer calories than sugar. So taken in isolation, instead of sugar, they will contribute to weight loss. But real people don’t eat just foods sweetened with artificial sweeteners. Both kids and parents adopt compensating behavior when it comes to sweets—persuading themselves, for example, that the calories they’re saving by drinking diet sodas give them license to indulge in their sweet tooth at the candy counter or for dessert. So in the end they may actually continue to eat the same total number of calories (or even more) on average.

But what really concerns experts about artificial sweeteners, especially for children, is that they are creeping into more and more products. And given the animal data, it’s legitimate to start investigating how they are affecting the human body, particularly among those who consume them from infancy on. Rother found that moms who use artificial sweeteners can pass on the agents in their breast milk, albeit in small amounts, so an entire generation may be exposed to these sugar substitutes from their first meal.

“I don’t know whether we are ever going to put questions about artificial sweeteners to rest,” says Susie Swithers, professor of behavioral neuroscience at Purdue University who has reviewed the animal and human studies to date on the compounds. “But I think what we need to do is really try to pin down whether some of the mechanisms we identified in animal models are actually operating in people. We also need to know whether the different artificial sweeteners are having different effects.”

That need for more research is among the few things that experts in the field agree upon. “Right now, based on our current set of studies in people, no one has shown in a [long term] trial that consuming diet beverages can increase your desire for sweet foods,” says Barry Popkin, professor of nutrition at University North Carolina. “We need more studies to give us a consensus. Because now there is no consensus.”

So how are well-intentioned and concerned parents supposed to shop for their kids? Lustig gives his parents this useful, if unconventional analogy. “I liken artificial sweeteners to methadone,” he says, referring to the drug treatment for heroin addiction that’s simply a longer-acting opiate than heroin. Methadone is supposed to gradually and gently wean addicts off their drug habit, by evening out the super-highs they get from heroin and flattening out the experience until they can do away with both the heroin and the methadone. “Diet sweeteners are like methadone — they are better than sugar but the goal is to use them as a method of getting off sweeteners, and not as a substitute for sugar. So what I say is if you’re using artificial sweeteners as a way to kick a heavy sugar habit, then great. But if you’re using them as an excuse to keep eating sweet foods and substituting one reward pathway for another, then ultimately they are not going to be helpful.”

Sugar, he says, is supposed to be a treat, a once-in-a-while reward, rather than the staple it’s become at every meal, and in practically every food. Rother agrees. And working with that idea of sweets as an occasional treat, if she has to choose between artificially sweetened desserts and sugar-sweetened ones for her children, she goes with the real stuff. “At least you know what you’re eating,” she says. “Just eat a little less later on instead of fooling yourself.”