At the heart of every great business is a creative solution to a problem—and those solutions sometimes change the world. To assemble TIME's first annual list of Genius Companies, we asked our global network of editors and correspondents to nominate businesses that are inventing the future. Then we evaluated candidates on key factors, including originality, influence, success and ambition. The result: 50 companies that are driving progress now, and bear watching for what they do next.

Three or four times a year, Disney CEO and chairman Bob Iger crosses from his office on the Burbank, Calif., lot with a couple of fellow execs to Disney Animation Studios, where rooms have been prepared for them. In each, they are pitched a movie. Sometimes the films are no more than an idea, and the room just has some art boards and a director with a 15-minute plot outline. Others are more elaborate—the room for Frozen 2 included a video from a research trip to Norway, Iceland and Finland, a “tone reel” and a wall of index cards detailing themes and emotional threads. Sounds like fun—except that each room represents a $150 million bet on what, in four or five years, audiences will pay to see.

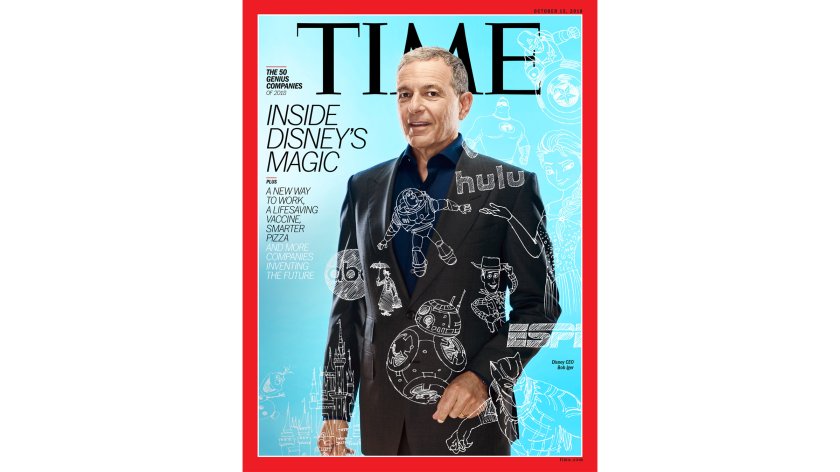

Iger, 67, is good at picking winners. This is, after all, the man who greenlighted America’s Funniest Home Videos. On his watch, Disney has released five of the top 10 grossing global hit movies of all time, selling a cumulative $8.4 billion worth of movie tickets. And not only did he sign off on those movies, he also spearheaded the purchase of the companies that made them, which requires prophetic skills of a whole different order. Apple CEO Tim Cook says Iger operates a lot like a tech-company CEO. “Both are trying to skate to where the puck is going and not where it is. We’re making calls years in advance.”

Of course, figuring out which films to make is a fundamental skill for any media mogul. What really distinguishes Iger from rival Hollywood CEOs—and what has insulated Disney from the vast shifts in viewing patterns that have battered others—is his conviction that an already gigantic company should keep getting bigger. While competitors mostly avoided risks at this scale, Iger spent lavishly to buy Pixar ($7.4 billion), Marvel ($4 billion) and Lucasfilm ($4 billion), giving Disney a lineup of moneymaking franchises that far outdistances competitors’.

Although some critics bemoan the sequelization of Hollywood, no one doubts that Iger’s moves have paid off. Audiences, most of the time, keep buying tickets. And “sequel” doesn’t actually do justice to Iger’s achievement: with the Marvel and Star Wars films, Disney has acquired entire fictional universes that can spawn lucrative new content in all directions. A Marvel movie character can power a new Disney theme-park ride, inspire a TV series and serve as the focus of a video game, all under the Disney tent.

More remarkable, in an industry of big egos, Iger’s relatively hands-off management style has allowed Disney to swallow these companies without masticating the qualities that make them unique. Industry observers say Iger’s collaborative approach has been critical to retaining the creative talent that made the properties worth buying—and in some cases, made those deals possible. (Iger famously took a Disney-Pixar relationship that had frayed under his predecessor and persuaded Steve Jobs to let Disney buy the animation powerhouse outright.)

When TIME set out to identify the most creatively successful companies in the world, candidates ranged from brilliant upstarts to household names. But even in that elite group, the Walt Disney Co. stands out. So far in 2018, Disney has released the top three U.S. box-office hits. And Iger has topped his own bigger-is-better strategy with a $71 billion deal to buy 21st Century Fox’s entertainment assets, bringing into the fold everything from Avatar to The Simpsons. Now the studio that began in the back of a real estate office by selling its first cartoon to one distributor in 1923 is poised to launch its own streaming service. By eliminating the middlemen and selling content directly to consumers, Disney will disrupt the disrupters. “I don’t think anybody else could do this but us, frankly,” says Iger.

In 2005, when Iger was named Disney’s sixth CEO, the company was in a rut. The brand felt dated, age-limited and low-quality. The previous CEO, the mercurial Michael Eisner, had some brilliant years and some not so brilliant, during the last five of which Disney stock fell by roughly a third. Iger was a veteran TV executive who had come to the company when it bought Cap Cities/ABC in 1996. Eisner’s deputy since 2000, he was seen by many as his faithful puppet.

Since Iger took control, however, the company’s market cap has grown fourfold, to $175 billion. It has delivered healthy total shareholder returns (488.5% vs. 212.6% for the S&P 500). Disney became the first company to put its shows on iTunes, and applied for over four times as many patents as before. Its theme parks, once reserved for Disney characters only, are full of Marvel, Pixar and Lucas attractions. More than 150 million people visited last year.

The successes have kept Iger bolted to the CEO chair in Burbank years longer than even he expected. Four times he has announced plans to retire, only to remain, outlasting several heirs apparent. He’s currently slated to retire in 2021, dashing (forever, says Iger) the dreams of friends, including Oprah Winfrey, who hoped he’d run for President as a business-friendly Democrat.

Wall Street has been happy to see Iger stay. “His record has been fantastic,” says Tim Nollen, an analyst at Macquarie Capital. “I think what he did right was recognize the company’s strengths and invest in those strengths.” Iger says the key to his strategy has been to put his money where the creators are. “Nothing is more important than the creators, the creative process and the creative output,” he says. “You’re basically making bets on people and ideas vs. anything else.”

He calls them bets, but Iger doesn’t really have a gambler’s style. He prefers to work as part of a syndicate that uses a well-tested system. The pitches at Disney Animation are more like long-running conversations than one-shot deals, an approach that feels relatively organic. “It’s not a big heavy discussion,” says Frozen‘s co-writer-director Jennifer Lee, who also runs the animation division. “By the time we arrive at what we feel is the right film to go next, he’s been on the journey with us the whole time and we’ve had a lot of smaller conversations. He definitely respects the process, that it’s an evolution.”

Iger’s franchise-heavy strategy also purposely leans toward favorites rather than artistic long shots. In a world where content is proliferating, he believes audiences opt for the most recognizable. “When consumers are faced with so much choice, it’s very helpful to them to know going in what something might be,” he says. Rather than creating movie stars, as the Hollywood enterprises of yore did, or elevating auteur-directors, as the Miramax-style studios did, Iger has focused on establishing brands. “He’s refined the business,” says Rupert Murdoch, executive co-chairman of Fox. “He built this thing around reliable franchises, whether it’s with Pixar, with Lucasfilm or with Marvel, which then play right into the theme parks and everything.”

Purchasing creative engines is not the same as dreaming them up—in the way that, say, Walt Disney did—but Iger’s ability to manage such enterprises has made his firm the go-to steward of cultural producers at a time of upheaval, when creators are looking for a safe harbor. How (other than fat checks) does he persuade people to hand over their brainchildren? “The negotiation is the small part of it,” says Apple’s Cook. “The big part is the vision.”

Former superagent Michael Ovitz, who details his short and unhappy tenure as a Disney CEO-in-waiting in his new book Who Is Michael Ovitz?, did deals for clients when Iger was head of ABC. He says Iger was the same kind of negotiator he is a CEO. “He’s quiet and strong and doesn’t pound the table,” Ovitz tells TIME, “but he gets his point across.” And when Iger lays out his vision, most people, from his board to his shareholders to Steve Jobs, assent.

Iger’s vision for Fox—along with some $71 billion—is what helped him land his biggest fish yet. “Rupert believed that where it was at the time, which was August of 2017, that Fox wasn’t necessarily as well set up for long-term success in the businesses that were transforming right before his eyes,” he says. Curiously, Murdoch puts it slightly differently. “Bob called into my place one day and we got talking, and he said, ‘Well, look, perhaps we should put everything together,’” says Murdoch, who was struggling to increase his company’s stake in the U.K.’s Sky at the time. “I thought it was a good idea. He probably hit me at a moment when I was frustrated.” (In the end, Sky went to Comcast, and Fox is selling its portion of the company.)

With the purchase of Fox, Iger is mustering the forces first grounded in creativity to take on the forces first grounded in delivery, such as Netflix and YouTube. In 2019, Disney hopes to launch its streaming service. This is a leap of faith of Summit Plummet proportions. The biggest generator of the company’s revenues is TV. Until recently, Disney sold its programming—especially ESPN—to cable companies for reliably large sums. But those profits are shrinking. ESPN has lost 11 million subscribers since 2013. More viewers abandon cable every month, while Netflix has 125 million customers, Amazon Prime 100 million and YouTube 1.8 billion monthly users. Disney’s hope is to lure people to its stream with content that can’t be found anywhere else. As tech upstarts pour vats of money into creating original programming—Netflix is spending $8 billion this year—Disney is sitting on a mother lode.

Iger thinks he knows how to coax consumers who already pay for one streaming service to either add another or switch to Disney’s. “We’re going to do something different,” he says. “We’re going to give audiences choice.” There are thousands of barely watched movies on Netflix, and Iger figures that people don’t like to pay for what they don’t use. So families can buy only a Disney stream, which will offer Pixar, Marvel, Lucas, Disney-branded programming. Sports lovers can opt just for an ESPN stream. Hulu, of which Disney will own a 60% stake after it buys Fox (and perhaps more if it can persuade Comcast to sell its share), will beef up ABC’s content with Fox Searchlight and FX and other Fox assets. “To fight [Amazon and Netflix], you’ve got to put a lot of product on the table,” says Murdoch. “You take what Disney’s got in sports, in family, in general entertainment—they can put together a pretty great offer.”

While folks stumble over themselves to praise Iger’s vision, and his execution thereof, fewer of them call him a visionary. His focus on brands has made him much less likely to be seen as the kind of artistic guru who gets thanked tearfully from the stage at the Academy Awards. “I think it’s safe to say what he does well is management,” says Brian Wieser, an analyst at Pivotal Research. “He’s never tried to be the thought leader in any particular sphere. There’s no one thing of which you’d say he was the oracle.”

This is not meant to be an insult. Finding talented people and setting up an organizational structure that allows them to do what they do well requires a particular form of wisdom. “He doesn’t lose anybody he doesn’t want to lose,” Ovitz says of Iger, who is reputed to regard his executives as more expendable than his creatives. “He gives them plenty of rope, and when there isn’t performance, he makes a change.” Adhering to this structure requires discipline, which, along with impeccable grooming, Iger is famous for; he rises at 4:15 a.m. and follows a fitness regimen that sometimes includes working out with his eyes closed as a kind of meditation. The discipline is both innate and acquired, largely by setbacks. “How you process failure at a company that thrives on great creativity is critical,” Iger says. “You can’t wallow. You have to know how to absorb creative disappointments, knowing that there are inevitabilities to that.”

Having a leader who is willing to insulate key creative people from the vicissitudes of business has helped Disney successfully incorporate its prominent acquisitions. They have not been Disneyfied. Marvel movies are not all of a sudden family friendly (at least not by Disney standards). Pixar movies have not been required to add princesses. Most of the people who ran the companies before Disney bought them still run them (with the exception of John Lasseter, who was ousted in June in the wake of #MeToo). “I’ve been watching him with his people and with Fox people; he’s clearly got great leadership qualities,” says Murdoch.”He listens very carefully and he decides something and it’s done. People respect that.”

Given what he’s achieved at Disney, Iger gets graded on a tough curve—and it’s about to get tougher. The animation division has lost its chief in Lasseter, and it remains to be seen how that changes the culture. Many of ESPN’s sports deals will need to be renegotiated within five years, and they’re only getting pricier. There’s evidence of franchise fatigue: the newest Star Wars film, Solo, did not blow the doors off the box office. And Iger still has to find someone to take over his job by 2021. On the plus side, fans will get a chance to fly the Millennium Falcon at the new Star Wars Land at both Disney World and Disneyland next year. Visits to the $5.5 billion Shanghai Disney park exceeded expectations. Over at the studio, director Lasse Hallstrom has taken on The Nutcracker, Tim Burton has taken on Dumbo, and Elsa and Anna have agreed to come back for Frozen 2.

Nobody is more excited by any of these developments than Iger, who has an almost boyish enthusiasm for what he does. He’s a consumer. He’s a fan. Before our interview he was watching the Sophia Loren—Clark Gable movie It Started in Naples in his office. The previous night he was listening to Queen, Nicki Minaj’s new album. (“I’m not prudish,” he says, “but she’s taken explicit to a whole new level.”) Iger insists that he’s not creative, which may be why he is such an adept partner of those who are. “My perfect day is a day where I’m engaged the most in creative processes and with creators,” he says. “Any day that has none of that is a bad day.”