A new study of the Supreme Court Justice’s accent says something about the way we all talk

By KatY STEINMETZ

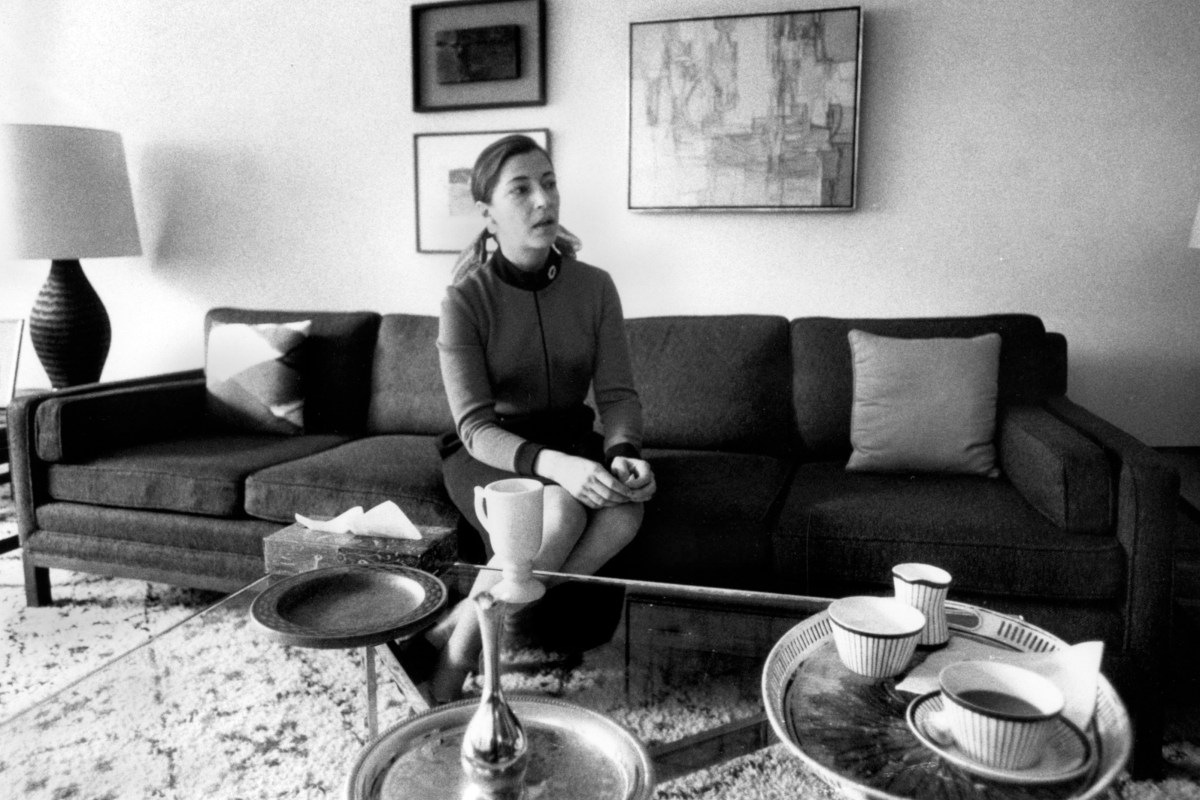

On Jan. 20, 1975, a lawyer named Ruth Bader Ginsburg stood before the United States Supreme Court. She was there to advocate on behalf of Stephen Wiesenfeld, a widower who had been denied Social Security benefits after his wife—a teacher and the primary earner in the family—had died. Though a widow would have had an easy time collecting that money, he did not, because those were considered “mother’s benefits.” At the time, women accounted for barely 5% of the attorneys who had argued in front of the highest court in the land. And Ginsburg was executing a far-sighted legal strategy in the pursuit of women’s rights: going after a law that ostensibly benefited her sex and hampered men.

Her client in that case, Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld, was fighting laws borne of a time when women generally were not expected to work unless circumstances forced it, while men were expected to see worth and obligation in their outsized ability to earn money. As she made her case, pausing to let each clause sink in, Ginsburg paraphrased the words of the first woman to serve as a district court judge in arguing why this unequal treatment of the sexes was wrong. Such “a gender line … helps to keep women not on a pedestal, but in a cage,” Ginsburg said, her words full and broad. It reinforces, she continued, the assumption that working for pay “is primarily the prerogative of men.” (Listen below.)

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/286170725″ params=”auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&visual=true” width=”100%” height=”450″ iframe=”true” /]

Her client won. The unanimous ruling was a milestone in the feminist movement’s push to level the playing field, at work and at home. Treating earnings as less or different because they were a woman’s and not a man’s was now contrary to equal protection under the law.

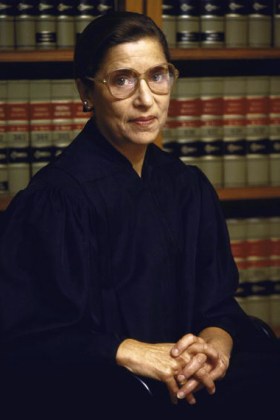

In that same courtroom about 35 years later, the woman who has become known as The Notorious RBG was speaking not from a lectern but from the bench, where she sat as the second woman to ever be appointed a Supreme Court Justice. She was reading the majority opinion in a 2010 case of an African-American man who had been convicted of murder by an all-white jury in Michigan years before. “The Sixth Amendment secures to persons charged with crime the right to be tried by an impartial jury,” Ginsburg said, “reflecting a fair cross-section of the community.” But while her speech remained careful and clear, something was different: Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s New York accent, subtle in 1975, was as noticeable as the decorative collars that have become her trademark. That’s according to a group of linguists from New York University. (Listen below.)

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/286170695″ params=”auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&visual=true” width=”100%” height=”450″ iframe=”true” /]

For three years, NYU linguistics professor emeritus John Victor Singler, along with researchers Nathan LaFave and Allison Shapp, pored over hours of audio of Ginsburg’s remarks at the Supreme Court. They used computer programs to analyze thousands of vowel and consonant utterances during her time arguing cases in the 1970s, and then from the early ’90s onward, after she returned to the court in robes. While one can hear flecks of classic New York features in Lawyer Ginsburg’s remarks—like the pursed, closed-mouthed vowels—her Brooklyn roots are more obvious in the speech of Justice Ginsburg, they found.

Their theory, reported here for the first time, is that “conscious or not,” the lawyer was doing something everyone does, what is known in linguistics as accommodation: adapting our ways of communicating depending on who we’re talking to. Accommodating can be done through word choice, pronunciation, even gestures. A common example would be when someone returns to the town where they grew up and their accent comes roaring back as they talk to friends and family who sound that way, too.

The difference the linguists detected may or may not tell us something about Ginsburg herself, who declined to be interviewed for this article. But the themes behind their theory are much more universal. Accents are markers of identity that we all have, evolving aspects of who we are that can lead people to make assumptions about us, for good or ill. And those assumptions often play out differently for men and for women, based not only on their gender but also on their ethnicity and their race.

“She was a female Jewish lawyer presenting before a Supreme Court that was made up mostly of white Protestants, at a time when feminists were being decried as strident and shrill-sounding,” LaFave says. The researchers have presented their findings at several conferences and an upcoming paper will set out the most comprehensive version of the research yet.

Though there are several salient features of New York City English, the group zeroed in on two: what linguists call the thought vowel and R-vocalization. The thought vowel is the one so central to pop culture characters like the star of the bygone Saturday Night Live sketch “Coffee Talk,” in which Mike Myers played a thick-accented New York woman who wandered into Yiddish and pronounced her show “kuh-aw-fee tuh-awk.” R-vocalization refers to the habit of dropping one’s R’s in certain words—a habit that gained renewed attention with the presidential campaign of Brooklyn-born Senator Bernie Sanders. Scores of other examples from decades of TV and film have conditioned audiences to think anyone whose accent has those features is a “noo yawker”—and often a stereotyped caricature of one at that.

Noting that Ginsburg moved to Washington, D.C., in 1980, the linguists argue that the sounds of her youth have come back in part because one of the most powerful women in America doesn’t have to fret so much about what people think these days. “Justice Ginsburg no longer needs to worry about whether she seems threatening to the Court,” they write in a working paper. “She is the Court.”

Ginsburg’s children, after having the study described to them, both said they cannot remember her accent altering over time. Her daughter, Columbia Law School professor Jane Ginsburg, who was about 20 when her mother started arguing Supreme Court cases, tells TIME that “neither my mother’s accent nor her speech patterns ever changed.”

The scope of the research is limited to Ginsburg’s utterances at the Supreme Court, one of the most formal, high-stakes situations in which a person could find themselves. Shifts in speech can also be difficult to detect, especially ones that creep in over time. Even well-defined accents can eventually shift. For example, fewer New Yorkers drop their R’s today than they used to. “Everybody actually has more than one accent,” says linguist and author David Crystal. “Everybody modifies their accent. Some people are so proud of a particular point of origin that they try their damnedest not to modify their voice, but this pressure to accommodate, as it’s called, is in everybody.”

The linguists’ argument also rests on another reality, one that affects millions of people: There is a form of bias that to this day remains widely unchecked. As Merriam-Webster editor-at-large Peter Sokolowski says, “Language prejudice is the last acceptable form.”

*****

Ruth Bader was born in Brooklyn in 1933, the daughter of a furrier peddling finery in the midst of the Great Depression and a mother who prized education. Her family would have confronted the social difficulties of being Jewish in an era when anti-Semitism could be found overtly painted on signs: “No Jews allowed.” It was in those days—before she went off to Cornell University, then Harvard Law—that the young Ruth would have been exposed to the sounds of New York City English. Beyond those in the NYU study, she might have taken in some of the dems and dats that have since fallen out of popular usage, or the dropped H’s (tink instead of think) and accentuated G’s (in words that sound like sing-ger).

In the 1970s, the second wave of feminism was going mainstream and women’s rights were taking center stage, while sexism continued to be pervasive and women continued to be told that their place was in the home. “When feminism hits the society… it’s like a typhoon. It goes rushing through,” Ellen DuBois, a professor of history and gender studies at UCLA, says of this moment in history. Feminists, she adds, were “sort of exotic creatures” in the early 1970s, often mocked as ear-aching complainers. Ginsburg, after becoming the first tenured female law professor at Columbia University, co-founded the Women’s Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union and devoted herself to the cause.

The Supreme Court was not immune to sexist notions that marked the time. Clare Cushman, director of publications for the Supreme Court Historical Society, points to a line from the autobiography of a justice whom Ginsburg argued before.

“‘I remember four women in one case who droned on and on in whining voices that said ‘Pay special attention to our arguments, for this is the day of women’s liberation,’” wrote Justice William O. Douglas, who retired from the court in 1975 and died in 1980.

Ginsburg was the 92nd woman to ever argue in front of the Supreme Court, according to an analysis done by author and lawyer Marlene Trestman. In 1966, Cushman says, only 1% of advocates making oral arguments before the court were women. By 1976, the number had reached 5%. By 2000, it was closer to 15%. Her position as a successful lawyer arguing historic cases was the exception to the rule. Ginsburg has said she had to work not only against anti-Semitism and hostility toward women, but that people like her had “to be sure you were better than everyone else” to overcome that sense of being other.

Research has found that when New York speakers are made conscious of their speech, or are in more formal situations, they tend to do things like pronounce R’s they might drop in casual conversation. While the NYU linguists used software developed at the University of Pennsylvania to analyze voice quality, it can be hard for untrained listeners to discern the properties of a vowel, especially outside extremes. An easier exercise is listening for the R’s.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/286170732″ params=”auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&visual=true” width=”100%” height=”450″ iframe=”true” /]

In a 1974 Supreme Court case, Ginsburg took the floor to argue that her client, a widower named Mel Kahn, should have gotten the same property tax breaks as widows in Florida, where he lived. As she asserted that this different treatment was really the byproduct of viewing a woman’s husband to be “her guardian, her superior, not her peer,” the consonants at the end of her words clicked into place like cabooses. (Listen above.)

Years later, Justice Ginsburg read the unanimous opinion in a 2012 case about frozen sperm, another one about death and money: If a widow uses her deceased husband’s frozen sperm to conceive children after his death, are those children entitled to inherit his Social Security benefits? As she explained the court’s thinking, words such as father and earner and survivor ended with more of an “uh” sound than an “er” sound—in other words, she wasn’t vocalizing some of her R’s. (Listen below.)

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/286170691″ params=”auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&visual=true” width=”100%” height=”450″ iframe=”true” /]

Could the shift simply be a function of Ginsburg’s voice changing as she got older? LaFave says the data don’t bear that out. When they compared her accent features as an advocate in the ’70s to those she first uttered after returning to the court as a justice in 1993, they found the later sounds to have become significantly more “New Yorky.” But then that New Yorkiness fluctuates over the ensuing years. If it were simply a factor of aging, LaFave says, one would expect the features to only become more pronounced as time went on.

*****

From g-droppin’ Appalachia to surfer “brah”-tastic California, one would be hard-pressed to find a corner of the United States where linguists have not parsed the wildly different ways Americans wield a shared tongue. Many of those accents come with well-known stereotypes attached, yet few American dialects carry more baggage than the mid-century New York vernacular.

In a landmark 1962 study, linguist William Labov showed that the characteristic R drop was associated with a lower position on the socio-economic ladder. He did this by studying the speech habits of department store salespeople—a group of workers who had already been shown to make attempts at “borrowing prestige” from their customers in another analysis. Labov observed the way in which the words “fourth floor” were uttered by salespeople at three large department stores in Manhattan, from the top (Saks Fifth Avenue), middle (Macy’s) and bottom (S. Klein) of the price spectrum. His hypothesis: the fancier the pants, the more pronounced the R, which is precisely what he found.

That isn’t all he found. To get the salespeople to naturally utter the phrase, he posed as a customer inquiring about the location of a department he already knew to be on the fourth floor. After each time he asked, he pretended he didn’t hear their answer, saying “Excuse me?” Made more self-aware of their speech, salespeople in every store were more likely to pronounce their R’s when answering for the second time. “They wanted to lose their accents,” a New York Times columnist concluded when recreating the study in the 1990s.

Following up this study with interviews of New Yorkers, Labov came to describe residents of that city as suffering from “linguistic self-hatred.” He found that two-thirds of New Yorkers thought outsiders didn’t like their speech. “They think we’re all murderers,” an older working-class Irish man told him. “To be recognized as a New Yorker,” a middle-class Jewish woman said, “that would be a terrible slap in the face!”

Even if a listener has neutral or positive feelings about a regional accent, it has the potential to be distracting. Just ask anyone with a strong accent who has been trotted in front of a group of people from another part of America and asked to speak for the group’s amusement. Lisa Wentz, a speech coach in San Francisco, recalls a doctor from Boston who sought her out so she could learn a more “general” American accent after colleagues and patients made her feel like a novelty they weren’t taking very seriously: “Listen to how cute her accent is!” Wentz estimates that eight out of 10 clients she gets wanting to adopt a less noticeable accent are women. Some of them are just tired of answering the constant question of “Where are you from?” Others “confide in me that they’re belittled,” she says, “that the focus is so much on their accent… that they’re not being heard on content.”

It’s hard to imagine that Ginsburg, who is renowned for being meticulous, observant and well-prepared, wouldn’t have been aware of the negative connotations of the accent—or influenced by the idea that she might want to eliminate every possible distraction from the merit of her arguments. That is not to say Ginsburg deliberately set out to erase New York features from her accent, but she may have been more apt to “converge”—a type of accommodation in which people adapt to the way others around them communicate to lessen social distance.

Even infants converge, the linguist and author Crystal says, talking in higher-pitched babbles to Mommy and lower-pitched babbles to Papa. “The majority of people will say on first acquaintance with you, ‘Oh, I don’t have an accent,’” he says. “But it only takes the slightest spark for an awareness to dawn that you have one.”

There is no shortage of scientific support for the notion that “dialect prejudice” exists. Studies have found that by age five, children prefer native-sounding speakers to foreign-accented speakers, regardless of whether they understand the words. Studies of adults have found that different accents trigger different presumptions about the speaker’s social power, abilities, honesty or even sex appeal.

Maybe the shift that the linguists found in Ginsburg’s speech is on the whole insignificant; certainly it is compared to her influence on the law and the lives of millions of people in America. But their theory speaks to a broader tendency we have to judge others before getting all the facts.

As Ginsburg herself once said: “I am fearful, or suspicious, of generalizations. … They cannot guide me reliably in making decisions about particular individuals.”