Raqqa Is in Ruins, and ISIS in Retreat

The flag of a U.S.-backed militia is raised in Naim Square, once the site of executions by ISIS.

The flag of a U.S.-backed militia is raised in Naim Square, once the site of executions by ISIS.

When Ahmed Hassan was a child, he played soccer in a stadium in the center of Raqqa, a Syrian city on the banks of the Euphrates River where he grew up. Generations of kids like Hassan remember playing on its fields. But when Islamic State militants took control of the city in 2014, the stadium became a prison. The locker rooms were turned into cells, with cages where men were kept in solitary confinement. It was here where the last ISIS fighters staged their final stand as the city they once styled as their capital was recaptured in October by an alliance of Syrian militias backed by U.S. airpower.

Hassan, now age 33 and a media officer for the militias known as the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), was among the first to visit the stadium as bulldozers razed debris from the battle. “I don’t know how to explain how I feel,” he said. “First, there’s joy that the city is finally liberated. There’s sadness too, as I remember my friends who died as martyrs here.”

Also, Raqqa is now in ruins. More than 4,450 airstrikes by the U.S.-led military coalition and others have left its streets a moonscape of shattered buildings and mountains of detritus. What was once a city of 200,000 is now all but deserted. Clouds of flies hover near collapsed buildings, a sign of the bodies crushed beneath. The Baghdad Gate, a brick relic from the 8th century, stands over the skeletons of slain ISIS fighters that lie in the open air, their flesh eaten away by dogs.

When the SDF announced the liberation of Raqqa on Oct. 17, it marked the fall of the Islamic State’s global nerve center. Here was where ISIS first consolidated control of an urban population, before it swept over the border into Iraq, capturing the city of Mosul and coming within 37 miles of Baghdad. In June 2014 the group’s leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, hailed the establishment of an Islamic “caliphate” to rule over not just the 10 million people in the swaths of Iraq and Syria that the group would control at its height. The claim of leadership extended to Sunni Muslims around the world, who were urged to join an army that had taken vast territory with lightning speed.

With the fall of Raqqa, this idea of a caliphate is at an end. No longer in control of any major city in Iraq or Syria, ISIS is on the verge of defeat as a conventional military force. The fighting is not over completely, but the remaining 3,500 to 5,500 militants are confined to a series of towns along the Euphrates and a stretch of desert straddling the Iraq-Syria border.

What remains is a country split into pieces as Syria’s bloody civil war rolls into a seventh year. In the country’s east, the SDF, a coalition of militias dominated by Kurdish armed groups, has taken over a sizable chunk of the country, aided since 2014 by U.S. airpower and special forces. In Syria’s west, the regime of President Bashar Assad has consolidated its hold on the country’s main population centers, including Damascus and Aleppo. Backed by Russian airpower and Iranian military aid, Assad has nearly defeated the Islamist-dominated rebel groups spawned in the chaos of Syria’s 2011 revolution. The insurgents still hold scraps of territory, but they have no hope of challenging Assad’s hold on power.

As each alliance eats up more and more territory formerly held by the Islamic State, they come closer to a standoff. If Assad follows through on his vow to reclaim the whole of the country, his forces will be pitted against the Syrian Kurdish fighters, who are unsure of how long the U.S. will lend them support. The empire of the Islamic State is in ruins. No one yet knows who will rule over the rubble.

A view of the clock tower square, where ISIS would carry out executions.

A view of the clock tower square, where ISIS would carry out executions.

A member of the People’s Protection Units (YPG) takes a selfie atop a destroyed bus.

A member of the People’s Protection Units (YPG) takes a selfie atop a destroyed bus.

Members of the Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) in Naim Square, formerly a site of public executions.

Members of the Women’s Protection Units (YPJ) in Naim Square, formerly a site of public executions.

A man walks on the bleachers of the stadium used by ISIS as a jail.

A man walks on the bleachers of the stadium used by ISIS as a jail.

A little less than seven years ago, Raqqa was a diverse and lively regional capital. From the 1950s onward, the growth of agriculture brought farmworkers and government employees from across the country, swelling the population. Some of the city’s former residents have fond memories of cool evenings along the river. “In our memories, it’s a beautiful city beside the river. Everyone from Raqqa has a memory of those riverbanks,” said Ibrahim Hassan, a lawyer and opposition activist who is now an official with the Raqqa civil council, a provisional government in charge of overseeing reconstruction.

The trouble began in March 2011, when protests broke out here and in Syria’s other main cities amid the Arab Spring revolts. People in Raqqa continued to march even as government troops rounded up demonstrators and tortured them, opened fire on crowds and sent the military to restore order. Civil protest turned to armed insurrection, and Raqqa fell into rebel hands in March 2013. Chaos reigned as rival rebel groups took control of different parts of the city.

The most powerful fighters were the Islamists, including the conservative Ahrar al-Sham and Jabhat al-Nusra, a group now known as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham that was linked to al-Qaeda at the time. But none were more powerful, or more distinctive, than the fighters of the Islamic State. Their uniform was the shalwar kameez, a loose-fitting outfit from the Indian subcontinent that was nearly unheard of in Syria. “They opened their centers in every neighborhood. We knew something was going to happen, because they didn’t mix with the people,” remembers Hassan.

ISIS crushed the other rebel groups in Raqqa over the remainder of 2013, using a car bomb to wipe out one rival brigade. From there, the group spread its tentacles into Iraq and Syria. Raqqa became the purest example of the Islamic State’s experiment in jihadist governance. ISIS carried out public executions, displaying severed heads in a public square. Satellite dishes, cell phones and music were banned. The tiniest infraction could provoke a beating or arrest by the hisba patrols, the religious police. A man named Mohamed Qassam, 59, told TIME he was beaten for saying, in an argument with his wife inside a government office, “I swear by my honor,” rather than “I swear by God.”

Hundreds of burned AK-47s inside an ISIS warehouse.

Hundreds of burned AK-47s inside an ISIS warehouse.

A destroyed ATM.

A destroyed ATM.

A ruined car.

A ruined car.

A street littered with rubble.

A street littered with rubble.

A dismantled sofa in a destroyed room.

A dismantled sofa in a destroyed room.

The group’s aspiration to build a state was fatally undermined by its other ideological aim, which was to provoke an apocalyptic confrontation with its opponents. Following ISIS’s sweep across Iraq, its massacres of Yezidis and the videotaped executions of American journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff, former President Barack Obama sent the U.S. back to war in the region in September 2014. U.S. and allied countries deployed airpower, artillery and special-operations forces to support Iraqi and Syrian forces fighting back against ISIS—an effort that has continued under President Donald Trump. After more than two years of fighting, Islamic State militants fell back to their main prizes. In Iraq, they fought for Mosul, the largest city they had captured. In Syria, they fought for Raqqa, their de facto capital. Mosul fell in July after nearly nine months of fighting by Iraqi forces, some of the most intense urban fighting since the end of World War II. In Raqqa, the battle was different.

Unlike the Iraqi military, with its tanks and armored vehicles, the SDF are lightly armed, and the militias required even more intense air support during the battle for Raqqa. In August alone, U.S.-led forces loosed more than 5,775 individual bombs, shells and missiles into the city. As a result, the destruction in Raqqa is complete, with the city totally empty of its inhabitants. In interviews, some former residents said the coalition’s shelling was the reason they fled the city in the end. A 47-year-old artist from the area who asked to have his name withheld because he believes his son is still in ISIS custody said an airstrike on a hospital in the village of Maysaloon prompted him to flee with his family. “The whole village escaped,” he said.

The ultimate toll on civilians is a matter of dispute. Airwars, a monitoring group based in London, reported that 433 civilians likely died as a result of U.S.-led strikes on Raqqa just in the month of August. Colonel Ryan Dillon, a spokesman for the U.S.-led coalition, said the military has not yet been able to assess the deaths claimed by Airwars but said the coalition “strikes only valid military targets.” Still, some civilian deaths may be uncovered as the rubble is slowly cleared away. Michael Enright, a British actor who volunteered to fight with the Syrian militias battling ISIS, described an incident during the final days of the battle where he spotted a civilian and an ISIS fighter through the scope of a sniper rifle in a house across the front line. “I’ve got all these moral dilemmas going on inside of me and getting ready to shoot, and an American airstrike comes in and just goes bang with that house and the one next door,” he said. “I thought, Well, no more moral dilemma.”

A view inside an ISIS warehouse.

A view inside an ISIS warehouse.

Cement blocks fill a window frame at the warehouse.

Cement blocks fill a window frame at the warehouse.

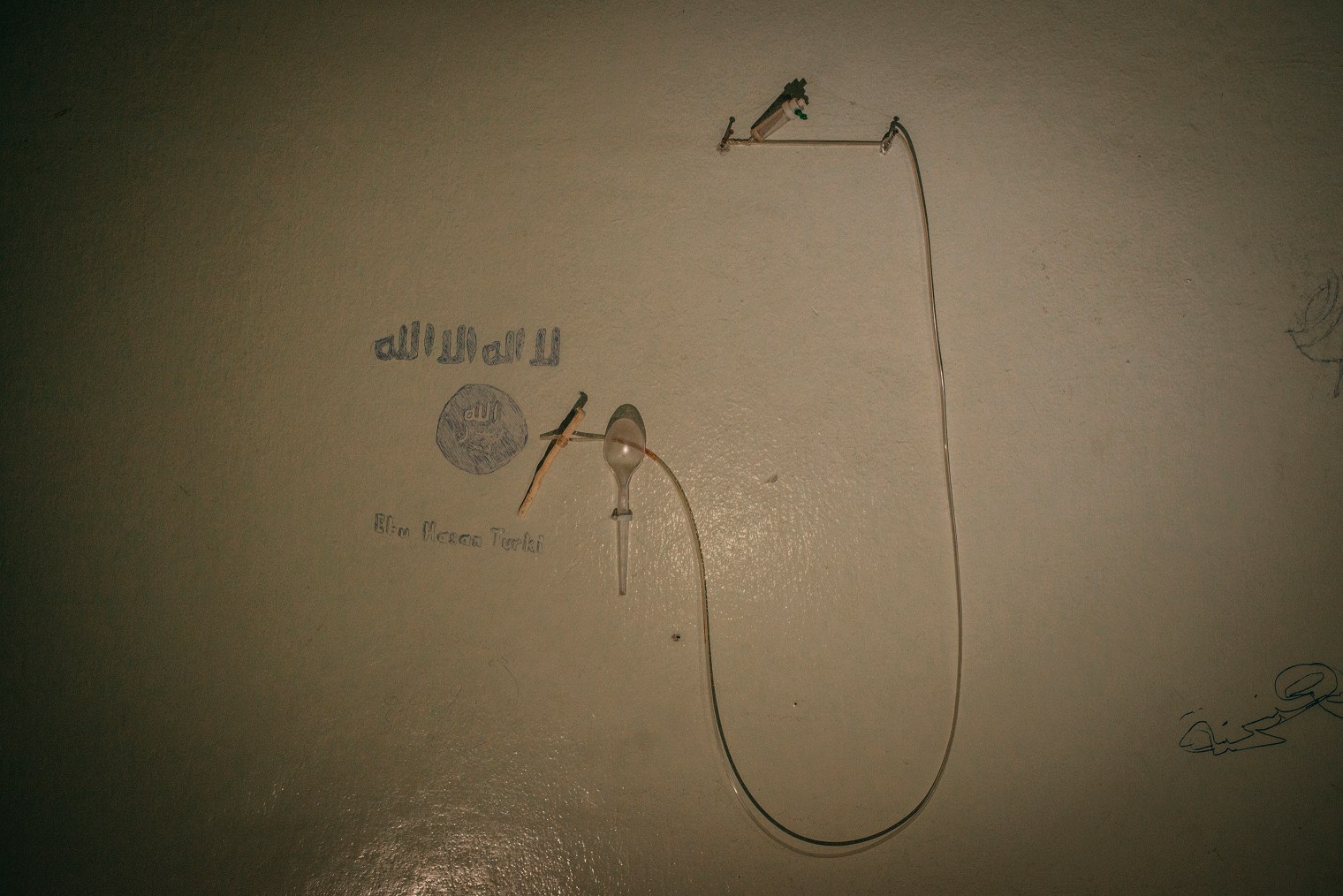

An intravenous tube hangs on a wall in the basement of the stadium used by ISIS as a jail.

An intravenous tube hangs on a wall in the basement of the stadium used by ISIS as a jail.

A member of the Syrian Democratic Forces walks inside the prison set up by militants in the basement of the stadium.

A member of the Syrian Democratic Forces walks inside the prison set up by militants in the basement of the stadium.

After a grueling four months of urban fighting and heavy bombing by American warplanes, the SDF trapped a few hundred remaining Islamic State gunmen in a tiny sliver of the city. After weeks of siege, 275 Syrian fighters among the ISIS core agreed to leave with their families in mid- October. In a deal brokered by local officials, they were evacuated on buses, leaving a few dozen foreign fighters to die as the militias moved in. “We didn’t find any of them. All of their bodies are under the buildings. We can only smell them,” one SDF member told TIME.

The caliphate’s fall doesn’t mean the end of ISIS. In Iraq and Syria, the group will live on as an insurgency that is expected to attack civilians and harass opposing forces for years to come. Satellite “states” have emerged in ungoverned spaces within Libya, Egypt, Afghanistan and the Philippines. ISIS is also expected to continue its campaign of terrorism across the world, either by trained operatives or self-motivated attackers. In 2016, the group’s leaders urged potential foreign recruits not to travel to Iraq and Syria, and instead launch “better and more enduring” attacks at home. At least 5,600 people have returned to 33 home countries after traveling to Islamic State territory, according to the Soufan Center, a security analysis firm in New York. Still, the state that the group for years boasted “remains and expands” now exists only in the group’s propaganda. The project of statehood begun by al-Baghdadi—whose fate is unknown—is at an end.

YPG fighters clear mines from a building.

YPG fighters clear mines from a building.

In Raqqa, the liberation was celebrated as a great victory by the Kurdish forces. On Oct. 19, the Kurdish-led women’s militia held a celebration in Naim Square, where ISIS had been known to carry out public executions. There, the militia raised a huge banner bearing the face of Abdullah Ocalan, the incarcerated founder of the militant Kurdistan Workers’ Party, considered a terrorist group by the U.S. for its attacks within Turkey.

The victory celebration began with a convoy of vehicles carrying female militia members honking and cheering as they circled the square. The fighters descended from the trucks carrying their assault rifles and assembled in rows under Ocalan’s portrait. Among them were teenagers from Raqqa, recruited out of nearby displacement camps. One, who called herself Belasan, said she was 17. Another, Suria, was 15. A commander, Rojda Felat, who co-led the assault on Raqqa, confirmed that the group recruits children. “Arab culture is different. They have problems in their families like getting married at a young age,” she said. “We never take them to fight until they’re 18.”

Images of the event were broadcast across the region, leaving U.S. officials red-faced. Here was the U.S.-backed militia proclaiming its victory in Raqqa by raising the banner of a group Washington has labeled terrorists. The U.S. embassy in Ankara felt obligated to reiterate that Ocalan was “not worthy of respect.” A U.S. official said the military raised concerns to the SDF about the ceremony. “We’ve talked to them for two years about this. Symbols mean something from both sides,” said a U.S. military adviser who was present during the meeting.

It was a symbol, too, of the thorny problem with “friends” of the U.S. in Syria now that the fight against the Islamic State is all but over. Turkey, a key NATO ally, sees Kurdish-led militias in Syria as a terrorist group and a potential threat. In April, Turkey even launched airstrikes on the SDF, showing a willingness to endanger American soldiers working with them. In a parallel dilemma in Iraq, the U.S. finds itself allied with both sides in a growing fight between the government in Baghdad and the Kurdistan administration in the north. The U.S. has been arming, training and assisting the two in the war against ISIS, a fight that is now fading in political relevance as civil conflicts in both countries multiply.

These alliances complicate what could be a final chapter in the Syrian civil war. Although Assad essentially ceded the region surrounding Raqqa to Kurdish groups at the outset of the civil war, the Kurds fear that Assad will renew attempts to reconquer the entire country, including their autonomous region they call Rojava. The areas under Kurdish control include the country’s largest oil fields, a critical strategic prize for the government in Damascus. In Iraq, the government’s seizure of territory held by Kurds there has only heightened those fears. Trump’s strategy of confronting Assad’s ally Iran has also raised the risk of a proxy conflagration on the ground in Syria.

Lieut. General Paul Funk, the U.S. coalition commander, sat inside an air-conditioned tent at a dusty U.S. airstrip at Kobane, the first city U.S. bombs leveled to defeat ISIS. He had flown into Syria that morning, Oct. 21, to congratulate the SDF militia leaders on their victory in Raqqa. Confronted with questions about the geopolitical maelstrom surrounding the U.S. presence in Syria, he reiterated an axiom of U.S. policy. “My mission is to defeat Daesh,” he said, using a disparaging Arabic term for the group, “and that’s what we’re doing.” In other words, the war on ISIS exists outside the surreal complexity of the Syrian conflict.

Members of the Raqqa Civil Council in their Ain Issa office. The organization was recently created with the aim to govern, once those who fled the city return.

Members of the Raqqa Civil Council in their Ain Issa office. The organization was recently created with the aim to govern, once those who fled the city return.

Two young girls inside the Ain Issa refugee camp.

Two young girls inside the Ain Issa refugee camp.

Sunflowers inside the Ain Issa refugee camp.

Sunflowers inside the Ain Issa refugee camp.

The assault on the Islamic State offers Western powers a simplistic narrative of good against evil. It’s not hard to rally international opposition to warlords who rape women, behead dissidents and bomb European cities. But now that the fight is winding down, the realities of America’s role in the Syrian war is something Washington has to grapple with. “The U.S. can only really win in Syria and Iraq if it can move beyond defeating ISIS to creating some lasting form of security and stability,” said Anthony Cordesman, the Arleigh A. Burke chair in strategy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “At present, the U.S. lacks any clear plan to achieve this in either country.”

In Syria, there’s no easy answer. Keeping the approximately 900 U.S. troops on the ground risks a confrontation with the Assad regime and its backers. Withdrawing too quickly would expose the SDF to attacks by the same. Quitting Syria completely risks creating a vacuum for ISIS or a successor to regain strength. U.S. military officials say they have not received instructions from the Trump Administration stating whether U.S. forces will remain in northeast Syria for the long haul. However, a senior Administration official told TIME, “We don’t intend to repeat the previous Administration’s mistake of abandoning the fight against the terrorists without consolidating the gains we and our partners have made.”

On the streets of Raqqa, there are reminders everywhere of an urban society that was held captive by ISIS and later collapsed during the battle. The doors of some stores are ripped open. Here, a children’s toy store with miniature plastic trucks on the shelves, now caked in dust. There, a barbershop, now piled high with metal and debris. Inside one building was a huge stockpile of weapons that had been set on fire. Room upon room revealed stacks of blackened mortars and rockets. One entire room was occupied by a pile of AK-47s that had melted together, hundreds of guns fused by the flames into a gnarled metal statue. On the wall the blaze had left an indelible mark the shape of a flame, an echo of violence inscribed among the ashes. — With reporting by Elizabeth Dias/Washington