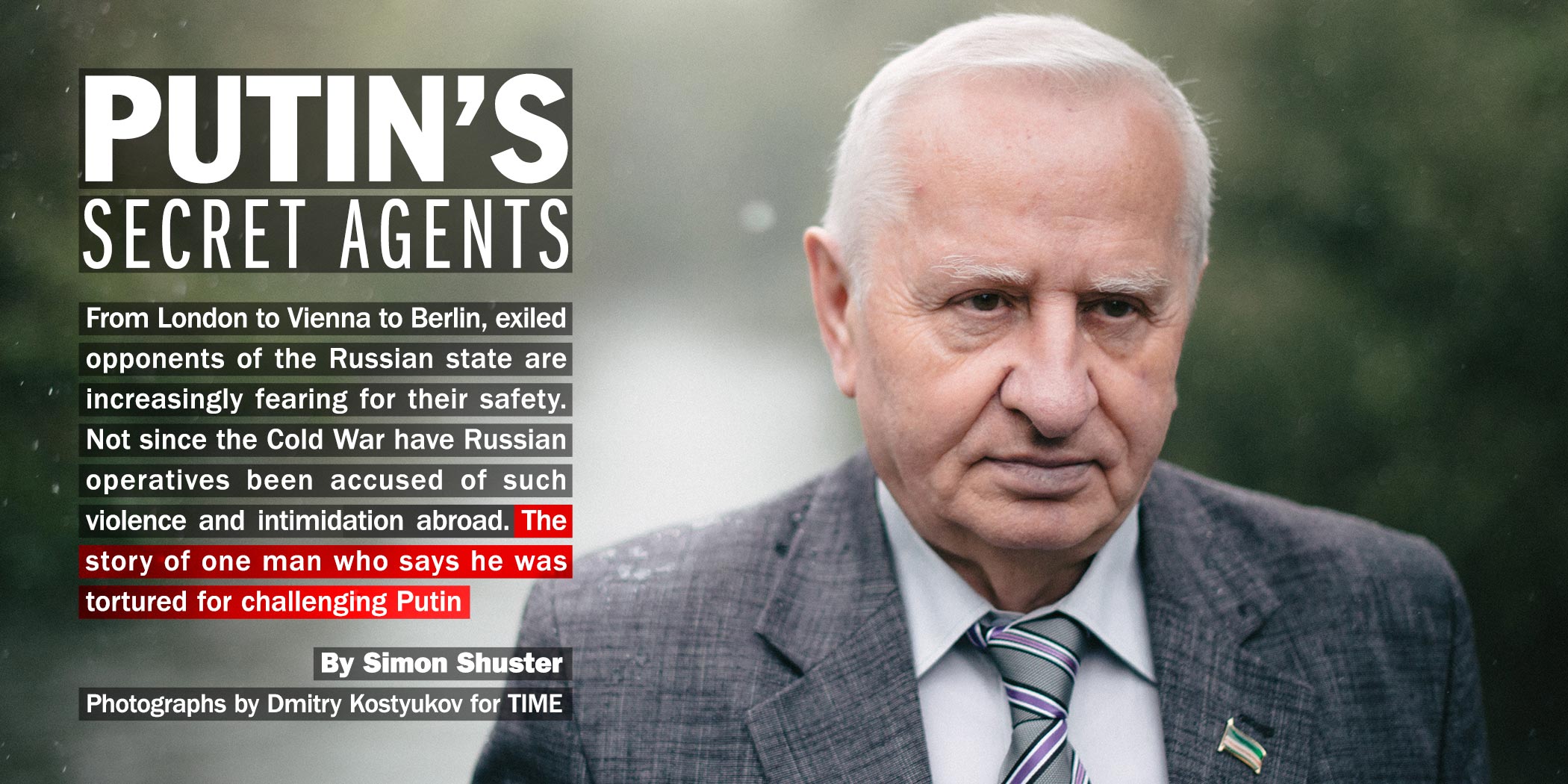

On a warm morning in early August, a 68-year-old Chechen man named Said-Emin Ibragimov packed up his fishing gear and walked to his favorite spot on the west bank of the river that runs through Strasbourg, the city of his exile in eastern France. Ibragimov, who was a minister in the breakaway Chechen government in the 1990s, needed to calm his nerves, and his favorite way to relax was to watch the Ill River, a tributary of the Rhine, flow by as he waited for a fish to bite.

Ibragimov had reason to be nervous. The previous month he had accused Russian President Vladimir Putin of war crimes in a criminal complaint he had sent to the International Criminal Court (ICC) and to the Kremlin. Ibragimov had taken five years to compile evidence of what he considered crimes committed during Russia’s two wars against separatists in the Russian republic of Chechnya. During the second Chechen war, which Putin oversaw in 1999–2000, Russia bombarded the Chechen capital of Grozny and killed thousands of civilians. The U.N. later called Grozny “the most destroyed city on earth.”

Ibragimov, who fled to France in 2001, was living out the last years of his life in political asylum but had continued to agitate against the Putin government, staging hunger strikes and sometimes one-man protests at sites like the European Parliament in Strasbourg. He had made his home in what he thought was a safe place—Strasbourg is also the seat of the European Court of Human Rights, and a city far from the countries on Russia’s borders over which Putin seemed increasingly determined to exert the Kremlin’s influence. But in his decade as a politician in Chechnya, Ibragimov had dealt with numerous threats, beatings and attempts to kill him, so what happened about an hour after he sat down on his folding chair on the banks of the Ill did not, in retrospect, entirely surprise him. As he stared at the nylon line he had cast into the sluggish current of the river, he heard a rustling in the trees behind him and, before he could turn, he felt a heavy blow to the back of the skull. It knocked him unconscious.

When he awoke, he tells TIME, he found himself blindfolded and in the custody of at least three men, all of them speaking Russian. Calmly at first, they urged him to stop “defaming their President,” but when Ibragimov told them in response that he “does not take orders from thugs,” the men began to beat and torture him, he says. The abuse continued over the course of nearly two days.

Ibragimov says the men spoke Russian with no accents—“like Muscovites,” he recalls, “definitely not Chechens.” He does not know who the men were, but from their accents, their words and their actions, he believes them to have been agents of the Russian government.

Ten days after the abduction, Ibragimov showed TIME the wounds he claims the men inflicted. Deep, yellowing lesions marked his chest—the result, he said, of lit cigarettes being pressed into his skin over and over again. Lifting the hem of his pants, he revealed several holes that had been gouged into his right calf by what had felt like metal spikes. The wounds were still oozing blood into the bandages doctors had applied when he later sought treatment. “They never let up,” he says of his attackers. “The torture was constant, constant, and it left me in no state to consider why this was happening.”

In a statement to TIME, the Kremlin said it had no knowledge of the attack against Ibragimov in Strasbourg or of his complaint against Putin to the ICC. “To our mind,” wrote Putin’s spokesman, Dmitri Peskov, in the statement, “the words of Mr. Ibragimov that he was kidnapped and tortured by ‘agents of the Russian state,’ as he stated, put his mental health in doubt.”

While it is not possible to say who was behind the attack on Ibragimov, the assault on the Chechen dissident comes at a time when the West is facing covert Russian activity at a level not seen since the end of the Cold War. Russia’s incursions in Ukraine, starting with the invasion and annexation of Crimea in March, have relied heavily on Russia’s clandestine services, which have proved adept at operating well outside of Russia’s borders. That has increased the concern among dissidents like Ibragimov and Western officials who fear an emboldened Kremlin might expand the reach of Russia’s security services beyond Ukraine. “Having seen how Russia acts within the framework of what we call hybrid warfare, I really don’t exclude anything when it comes to Russian operations in other countries,” says Anders Fogh Rasmussen, who recently finished his term as Secretary-General of the NATO alliance, which includes the U.S., the U.K., France and 25 of their allies. “Obviously that is a major concern.”

Even in major European cities like London, Vienna and Berlin, opponents of the Russian state have felt little safety in exile during Putin’s tenure as President. Dissidents and their European host governments have also found that acts of murder and intimidation can be hard to prosecute when their trails seem to lead back to Russia. In August, Russian authorities formally refused to cooperate with a British public inquiry into the 2006 murder of Alexander Litvinenko, a former Russian spy who was poisoned to death in London after he publicly accused Putin of mass murder. On his deathbed, Litvinenko said only Putin could have ordered the mission to kill him with a lethal dose of radioactive polonium, which had been slipped into the whistle-blower’s tea. The Kremlin denies any involvement in Litvinenko’s murder.

More recently, the Estonian government accused agents of the Russian FSB security service, the post-Soviet successor to the KGB, of kidnapping an Estonian security officer on Sept. 5 and taking him back to Moscow, where he is now facing charges for espionage. Though the FSB denied any cross-border incursion, the case has deepened fears in Europe that Putin, a retired colonel of the KGB who served as director of the FSB before becoming President, has ordered his security services to operate more assertively beyond Russia’s borders.

That alarms some of Putin’s opponents who live in exile in Europe. “It is something I have to live with,” says Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the former oil tycoon who spent a decade in prison in Russia after being convicted of tax evasion and fraud. (Khodorkovsky had become increasingly politically active and critical of Putin in the run-up to his arrest in 2003, and human-rights groups consider his prosecution to have been politically motivated.) Upon his release in December, Khodorkovsky took refuge in Switzerland and has continued organizing against the Putin regime from abroad, launching an online forum in September to help coordinate the Russian dissident movement and its supporters. While promoting the project on a recent visit to Berlin, he tells TIME he believes that his life is still in danger. “If Putin makes a decision to physically eliminate me, it will not be easy for me to survive, not even in Europe,” he says. “I accept this.” All the more so, he says, since Russia’s aggression in Ukraine “untied the hands” of the military hawks who have Putin’s ear in the Kremlin. “In his inner circle, there are people who are more and more inclined to the use of force, and we see that they carry out such operations,” Khodorkovsky says. “In Ukraine this was very clear.”

In Western Europe, officials say many operations conducted by agents of the Russian government go unnoticed or unreported. “The Russian security services themselves—not only the military, civilian and police, but also their proxies because they use a lot of proxies—are currently very, very active in the Western world,” says Arnaud Danjean, who previously served in the French military intelligence agency and now chairs the Subcommittee on Security and Defense at the Strasbourg-based European Parliament. Though Danjean had not been aware of the specific attack against Ibragimov, he says it would hardly be a novelty for Russia. “When you have a former KGB [agent] as the head of state, it is no surprise that you have these things occurring.”

The abduction in Strasbourg may not have been the first time Ibragimov had been a target for Russian operatives or people loyal to the Kremlin. In the spring of 2009, Ibragimov says, a lawyer with ties to the state’s prosecutor’s office in Paris gave him an investigative report written by a French prosecutor that describes an apparent attempt to kill Ibragimov that year. The report, whose authenticity was confirmed to TIME by a Ministry of Justice official whose name appears on the document, indicates that the French police had discovered and prevented a Russian-linked plot to kill several political refugees from Chechnya on French soil.

According to the report, which was written as a request to authorities in Turkey for information on a suspect, French investigators believed that the group of assassins could have traveled from Russia through Belarus and into the European Union to kill Ibragimov and several other “opponents” in France.

The document also states that in early March of that year, the counterterrorism section of the Paris prosecutor’s office opened a preliminary inquiry into the assassination plot against Ibragimov, seeking to “identify the team of killers, as well as any logistical support they could receive in order to carry out their deadly activities on French territory.” (French officials declined to comment on the outcome of the probe.)

The timing of the alleged 2009 plot coincides with the period when Ibragimov says he began researching the possibility of bringing charges against Putin at the ICC. It would soon become an obsession for him. The ICC, which is based in the Dutch city of the Hague, held some promise of closure, if not also justice, for the victims of Russia’s war in Chechnya in 1999–2000. That war re-established Moscow’s control over the separatist republic and helped launch Putin’s political career, but in the process thousands of Chechens were killed in Russian bombing raids, including many of Ibragimov’s relatives and friends. The war also forced Ibragimov to flee his homeland.

From his tiny apartment in a Strasbourg suburb called Ostwald—“my bachelor pad,” he calls it—he worked for five years, living off the government welfare that his French asylum affords him, to prepare his complaint to the ICC, accusing Putin of crimes against humanity and genocide. Most of the effort was spent harvesting potential evidence from open sources and studying all the relevant treaties and legal precedents that could apply to the case. He quickly realized that it was a hopeless—or at least quixotic—venture. Like the U.S. and more than two dozen other countries, Russia does not recognize ICC rulings against its citizens, because it has not ratified the court’s founding treaty, which is known as the Rome Statute.

But he was undeterred. “The Hague is the highest court of human rights,” he told TIME in Strasbourg during a series of interviews in August. “I just want them to make a final decision on the Chechen question, to put it to rest. Can Putin be charged with war crimes or not?”

When he finally finished the complaint in early July, it came to 98 pages of evidence, and he says he sent one copy to the Kremlin and one to the ICC’s chief prosecutor, Fatou Bensouda. Four weeks passed with no reply, except the threatening phone calls Ibragimov says he received on his cell phone. A Russian voice would come on the line from an anonymous number, he says, and advise him to “stop his foolishness.” Before the line went dead, the calm, almost plaintive caller would warn him that, otherwise, “something bad might happen.”

The threats did not come as a complete shock to Ibragimov. While serving as Chechnya’s Minister of Communications, during the republic’s brief run at independence in the 1990s, he survived an attempt on his life and faced countless threats. While rallying support in Turkey for the cause of Chechen independence in 1996, three men attacked him outside his rented apartment in Istanbul and stabbed him seven times. It took him several months to recover from those injuries.

In early August, after a month with no response from the ICC, Ibragimov decided to begin another hunger strike until the court gave him an answer, a push for publicity that began to make headlines in the online Chechen press. That’s when he says he was attacked on the bank of the river, just a few steps away from a leafy trail where French families walk their dogs and ride their bikes.

According to the sworn deposition he later gave police in Strasbourg, he was blindfolded, beaten and tortured. He recalls one of his captors telling him to stop his activism or he would wind up in Lubyanka, the former headquarters of the KGB in Moscow that now houses the FSB. “They never referred to Putin by name,” he says. “They just said I had defamed their President.”

When he tried to resist, Ibragimov says, his captors handcuffed him and began using torture to force him to sign a piece of paper he could not see. It also seems clear that his captors were not trying to kill him. He recalls one of the assailants telling another, “Don’t touch the left side [of Ibragimov’s chest]. He’s got a bad heart.”

The torment ended on Aug. 10 when, he says, he woke up in a patch of forest on the outskirts of Strasbourg and managed to walk to a nearby road, his clothes covered in blood. After receiving treatment for his injuries at a local hospital, he filed a report with the Strasbourg police, who opened an investigation into the alleged kidnapping and torture, according to a copy of the report. (A spokesman for the Strasbourg police confirmed that they are investigating the case but declined to comment on the progress of the investigation, citing official policy.)

What bothers Ibragimov the most about the French response is that authorities have offered him no protection, just as they failed to do after discovering the previous plot to assassinate him. Senior officials at the agency that worked on that case in 2009 did not reply to e-mailed requests for comment, and the only French officials who agreed to discuss it with TIME were current and former lawmakers and members of the European Parliament. One of them, who spoke on condition of anonymity, has known Ibragimov for years from his activism in Strasbourg, and he says he was horrified to learn of the attack. “He was always an earnest, serious gentleman, and he was very persistent,” says the lawmaker. “But he is harmless.”

That assessment seems correct. In a statement to TIME, a spokesperson for the ICC, Nicola Fletcher, said it would analyze Ibragimov’s charges. “As soon as we reach a decision, we will inform the sender and provide reasons for our decision.” But the result is something of a foregone conclusion; under the ICC mandate, it can only adjudicate crimes committed after its founding treaty came into force in 2002. The war in Chechnya ended two years earlier. So using violence to force Ibragimov to withdraw his complaint would make little practical sense—apart from a desire to repress any such allegations. Ibragimov also sees another possible motive. “They want to show that they can get to anyone, anywhere,” he says. “No one can stop them.” Not even in the heart of Europe.

—With reporting by Vivienne Walt/Paris, Naina Bajekal/London and Nikhil Kumar and Bryan Walsh/New York