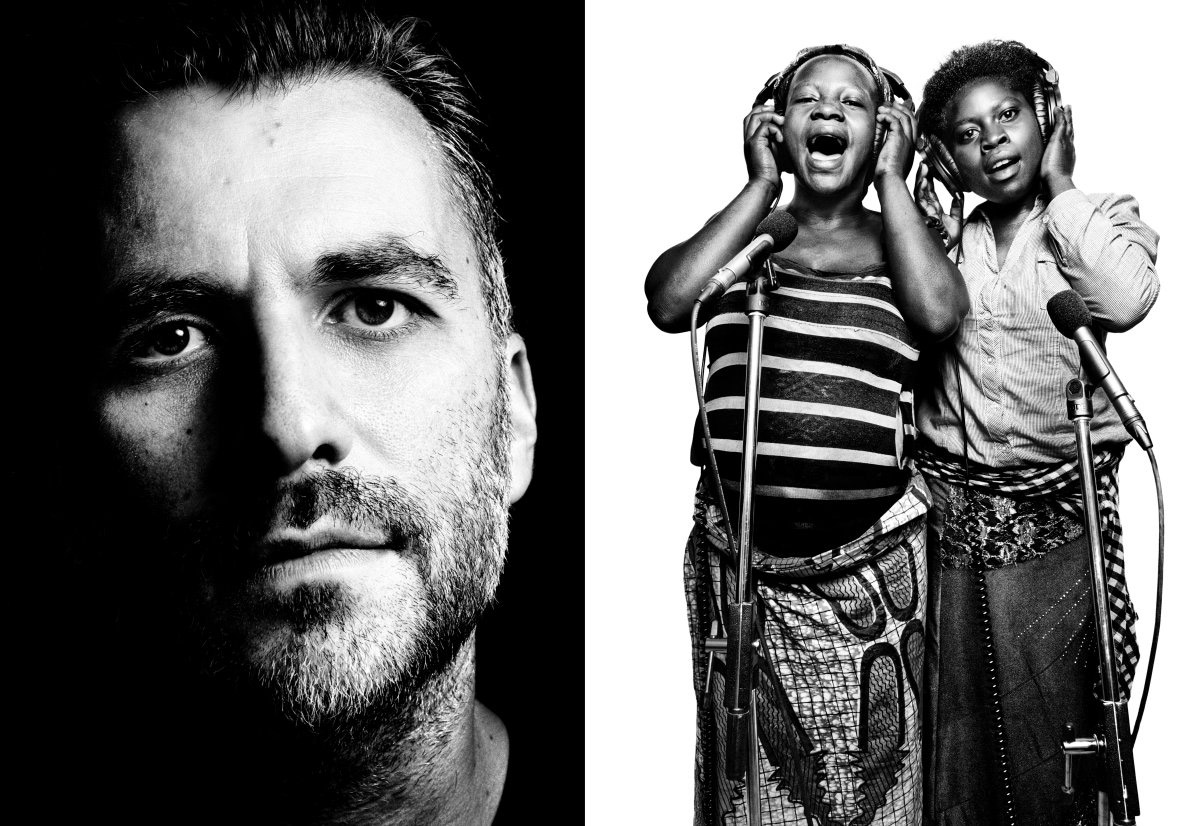

By Aryn Baker | Photographs by Platon

Heroes often come from the most unlikely of places. Photographer Platon, known for his unflinching close-up portraits of presidents, dictators and other powerful icons of our era, found his in the surgical suites and recovery rooms of a small-town hospital in one of the most traumatized nations on earth, the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Congo’s dark history spans centuries and lingers even into the present day. Though the most recent civil war ended in 2003, the scars of that conflict are carved deep into the bodies and psyche of the nation, most particularly its women. Rape has almost always been a part of armed conflict, but in Congo’s civil wars, it was a strategy. At least 200,000 Congolese women and children were raped during the seven-year conflict, in one of the most overt cases of sexual assault being used as a weapon of war.

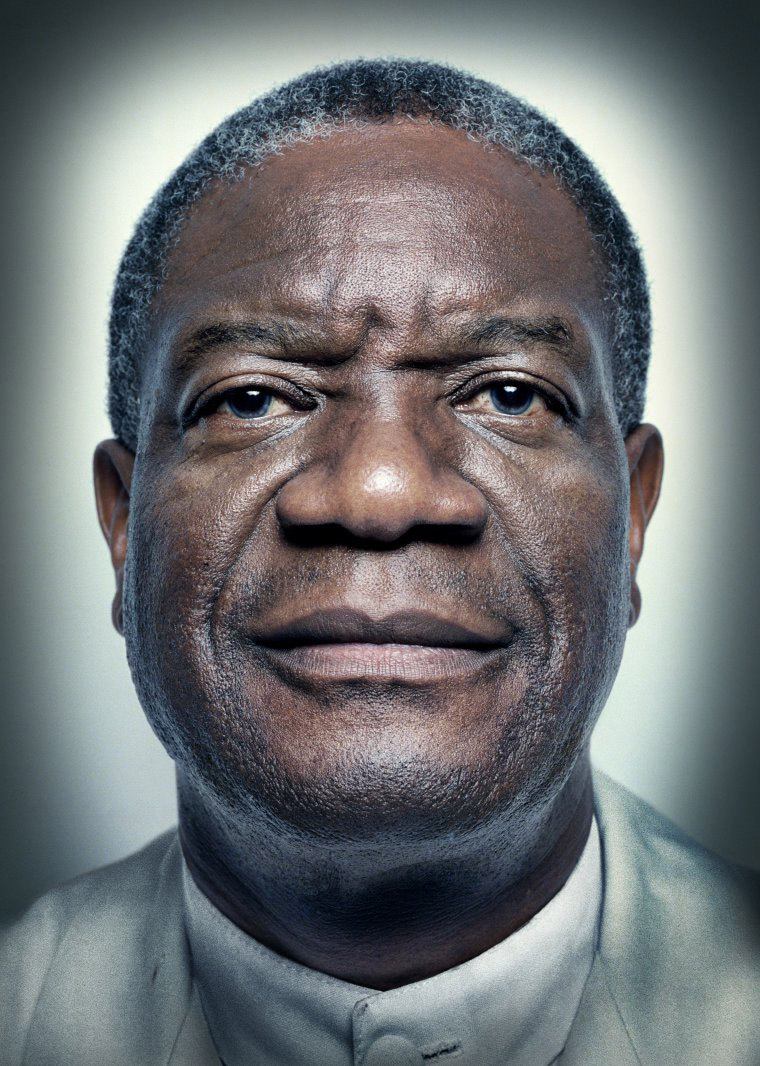

Panzi Hospital treats those women, and the tens of thousands more who have been violently raped since the war ended, victims of Congo’s wartime legacy of impunity. Platon, a friend of the hospital’s Congolese founder, Dr. Denis Mukwege, visited Panzi Hospital at the doctor’s urging last spring, to work on a documentary series for Netflix, Abstract: The Art of Design. This project was reported and researched in collaboration with Physicians for Human Rights and the Panzi Foundation USA, and funded by Platon’s charitable foundation, “The People’s Portfolio.”

“I went there expecting to be traumatized,” says Platon. “Instead I found incredible stories of courage.”

It is something of a dark irony that Congo, a country known to the outside world as “the rape capital of the world,” and the “world’s worst place to be a woman,” according to high-ranking U.N. officials, is also a center of excellence when it comes to the physical and psychological treatment of women who have suffered violent rape. Much of that is thanks to the efforts of Mukwege, a gynecological surgeon who founded Panzi in 1999 as a maternity hospital specializing in difficult deliveries. “His first patient was a woman that had been raped with extreme violence,” says Platon.

Mukwege hoped it was an outlier, he says, “but it turns out, as we now know, that it was just the first of many horrific incidents of how rape was being used as a weapon in Congo’s war.” Since then Panzi Hospital has treated 85,000 women, children and babies.

By dint of his copious experience treating rape victims, Mukwege and his team have become worldwide experts in repairing fistulas, the tears between the vagina, anus, bladder and bowel often sustained during sexual violence. But Mukwege’s work doesn’t end with physical healing. Through Maison Dorcas, a rehabilitation center that shares the same leafy compound as the hospital, patients are given the psychological help, skills and opportunities to knit their lives back together, turning rape victims into survivors.

Mukwege is also an outspoken advocate for women, for justice and for an end to violence against women. It is those characteristics that drew Platon to Panzi. “What I try to do as a photographer is find the new Martin Luther Kings, the new Gandhis, the new Mandelas, the new leaders who could become household names. We have more information than any other time before, but somehow we know less. So what I say is ‘let’s find the emerging leaders and give them a megaphone through my work, so they can be the spokesmen and women for these issues.’” When he is with Mukwege, says Platon, “I feel like I am photographing Gandhi in the 1930s. It matters deeply that we not just tell his story, but elevate his position and give him that platform that he deserves, that helps him fight his battles.”

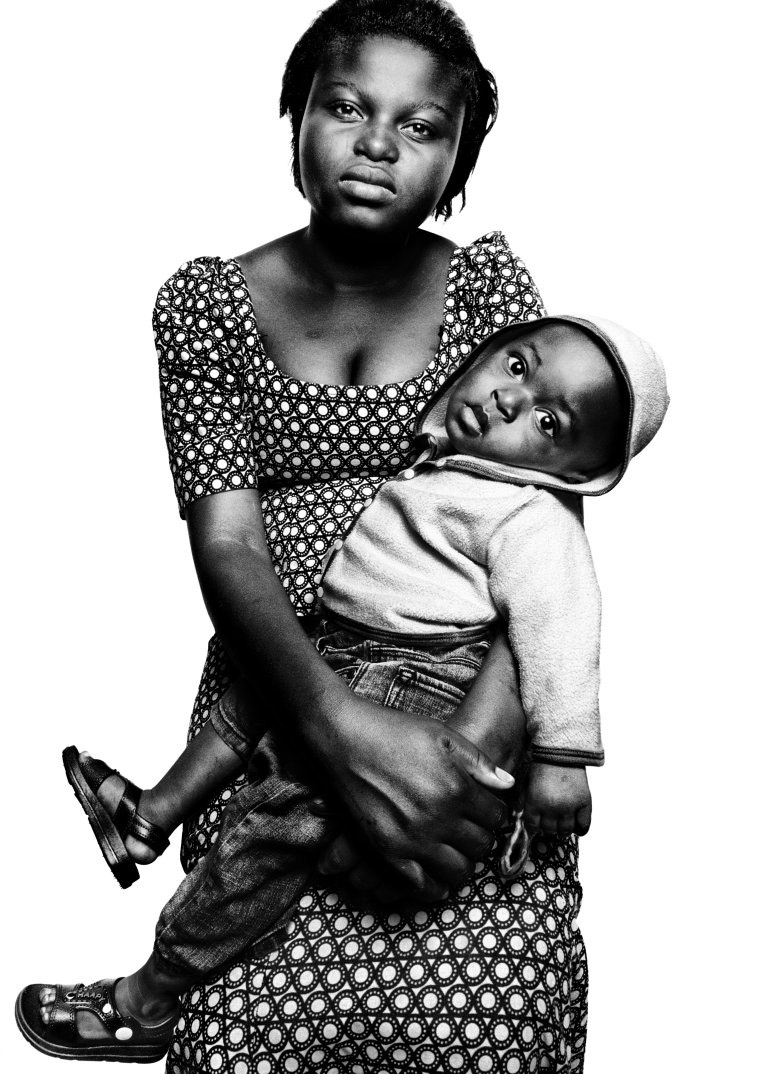

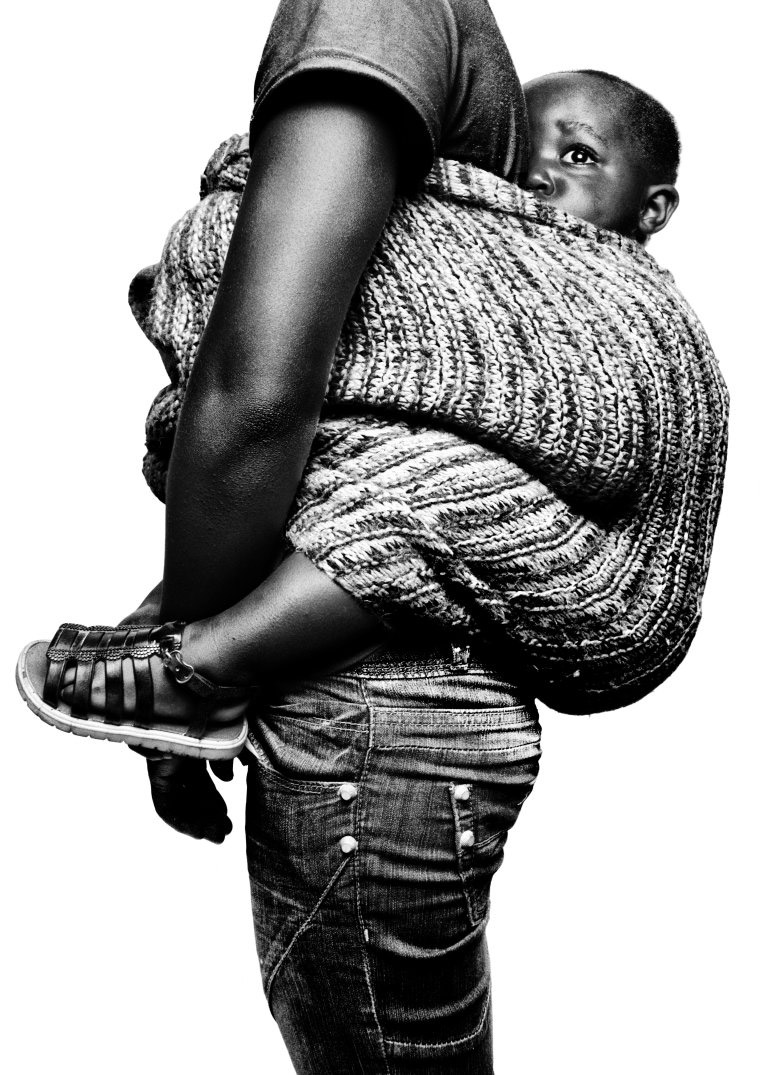

Platon spent 10 days in March 2016 with Mukwege, his team and his patients, documenting the everyday stories of hope, healing and happiness despite the pain that are the defining characteristic of the Panzi hospital compound. “I never expected to find this joy and strength at Panzi. I went expecting to see broken people, and I did, but what I also saw is that people can overcome that,” says Platon. “The women I photographed are the most inspiring people I have ever met in my life. I started to focus on their courage and heroism, and the idea of overcoming adversity.”

One young woman in particular stood out. Sandra, a 21-year-old who had been infected with HIV when her neighbor raped her at 16, has flourished at Maison Dorcas, where she is one of scores of women participating in its innovative music therapy program. She sings the title track on the program’s recently produced album, My Body is Not a Weapon. “When I sing, the bad memories disappear,” she tells Platon. Not only that, she has become an activist in her own right, penning poetry and music lyrics that are now being broadcast on local radio. Platon reads a few stanzas in translation:

“Within me a small president is hidden/ who would change all inequalities.

Within me a small lawyer is hidden/ who will defend all the oppressed.

And if I don’t make it, could you change the world for me?”

Overcome with emotion, he pauses for a moment. “When I took that picture of Sandra, when you read these words, it starts to make sense. She is a true leader. This is what our leaders need to understand. You have to think of serving the people first. Power comes from that, not the other way around.”

When he first opened Panzi hospital, Mukwege argued that rape in war was far more deadly than bullets. Guns killed immediately, he frequently explained to hospital visitors, but rape destroyed a community for generations.

In Eastern Congo, the repercussions are evident. Though the conflict is long over, the rapes continue, evidence of the corrosive effect its use as a weapon of war can have on society.

“Rape has infected Congo,” Jane Mukuninwa, one of Mukwege’s former patients, told me when I visited Bukavu in December 2015. “Rape kills society. Because now, we can see a father raping his own daughter, a brother raping his own sister, you can see a military soldier raping one of the citizens he is supposed to protect.”

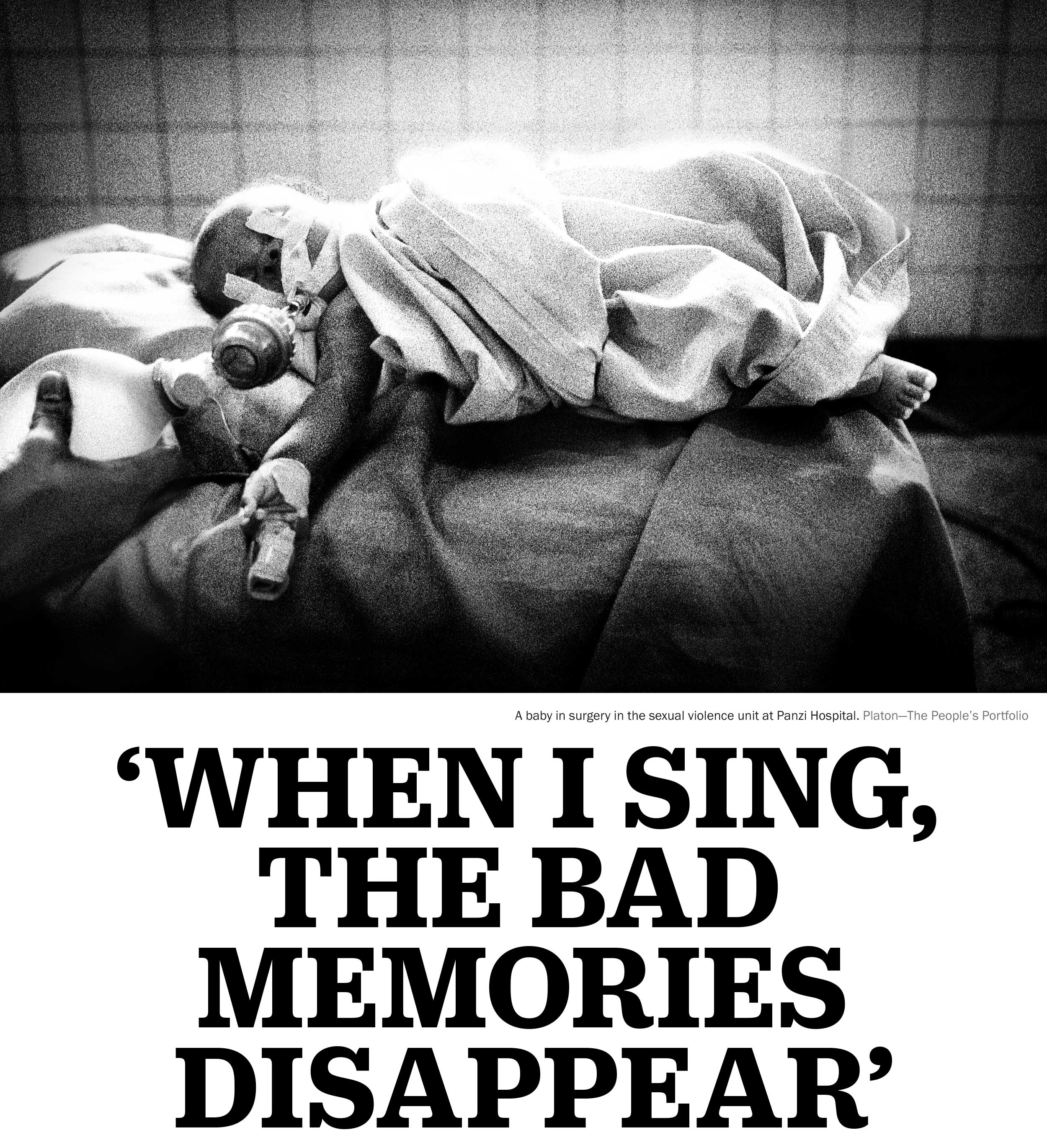

Dr. Neema Rukunghu, a gynecologist and the medical coordinator for Panzi Hospital’s center for survivors of sexual violence, told me that when she first started at Panzi eight years ago, she would see patients in their 20s, 30s and 40s. Now she is treating toddlers, even babies. In late 2015 she attended to a three-month-old baby girl who had been abducted from her parent’s house and returned a day later, ravaged and near dead.

A few months later, Platon witnessed surgeons operating on another infant girl. He doesn’t know the exact circumstances that brought her to the hospital, he says, but “what I can verify is that there are many cases of babies being treated for sexual violence at Panzi.”

Child rape, says Rukunghu, is the consequence of continued injustice—both during the war, and now—legacy of rape in war. What went unpunished as a war crime continues to go unpunished today.

“What this tells me, this evolution, I can tell you straight away that it is caused by impunity,” she says angrily. A man may believe that sex with a virgin girl, even one as young as three months old, may bring him wealth or cure disease, “but that is not why he does it. He does it because he knows that there is no prison waiting for him, no death penalty. He knows he can get away with it.”

For all the healing, training and recovery that Panzi and its doctors can offer, nothing is as good as stopping rape from happening in the first place, says Rukunghu. And while much of the responsibility goes back to Congo’s courts and security forces, the survivors at Panzi and Maison Dorcas can play their part.

By coming together, speaking out and telling their stories, in photographs and song, they are eradicating the fear of dishonor that has shielded rapists in the past. To Platon, that is true leadership. “I have photographed more world leaders than anyone. So when I am confronted with these stories, I see these women as leaders. It’s too simplistic to think of them as victims. They are victimized to be sure, but they are showing courage in allowing themselves to be photographed, and to use their stories to drive change.”

Originally published Feb. 15