Photographing the Dead

Jeffrey Silverthorne revisits a haunting series of photographs made at a Rhode Island state morgue in the 1970s

The photographs in Jeffrey Silverthorne’s new book Morgue, were made in 1972 and 1973, at the state morgue of Rhode Island. The 22 large-format photographs of corpses are intimate but discreet. In Silverthorne’s postscript to the book, he notes that when he made these photographs, he was 25 years old, had been married for four years, his second child had just been born and “the Vietnam War was still flowering death. Change and death were in the air, and the morgue was where I could find physical evidence.”

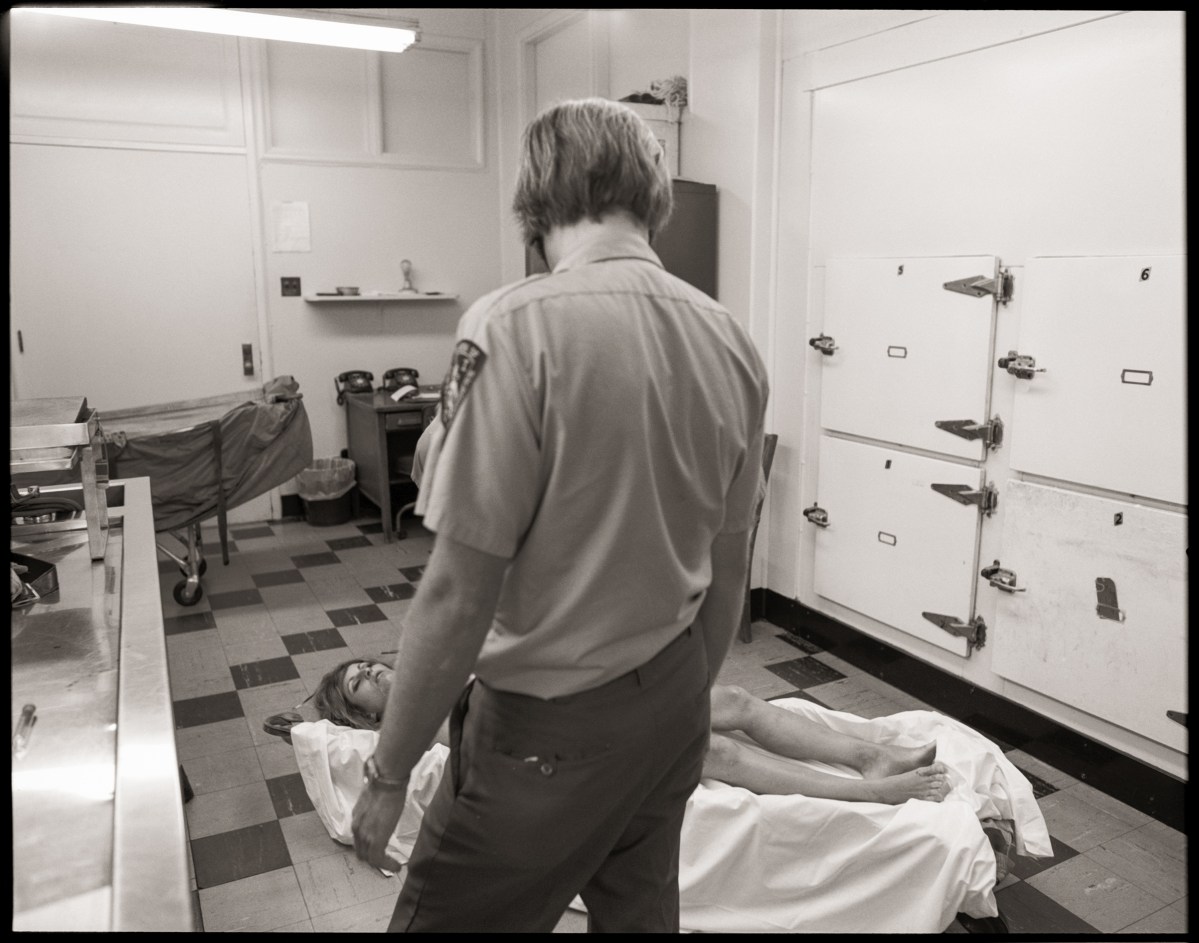

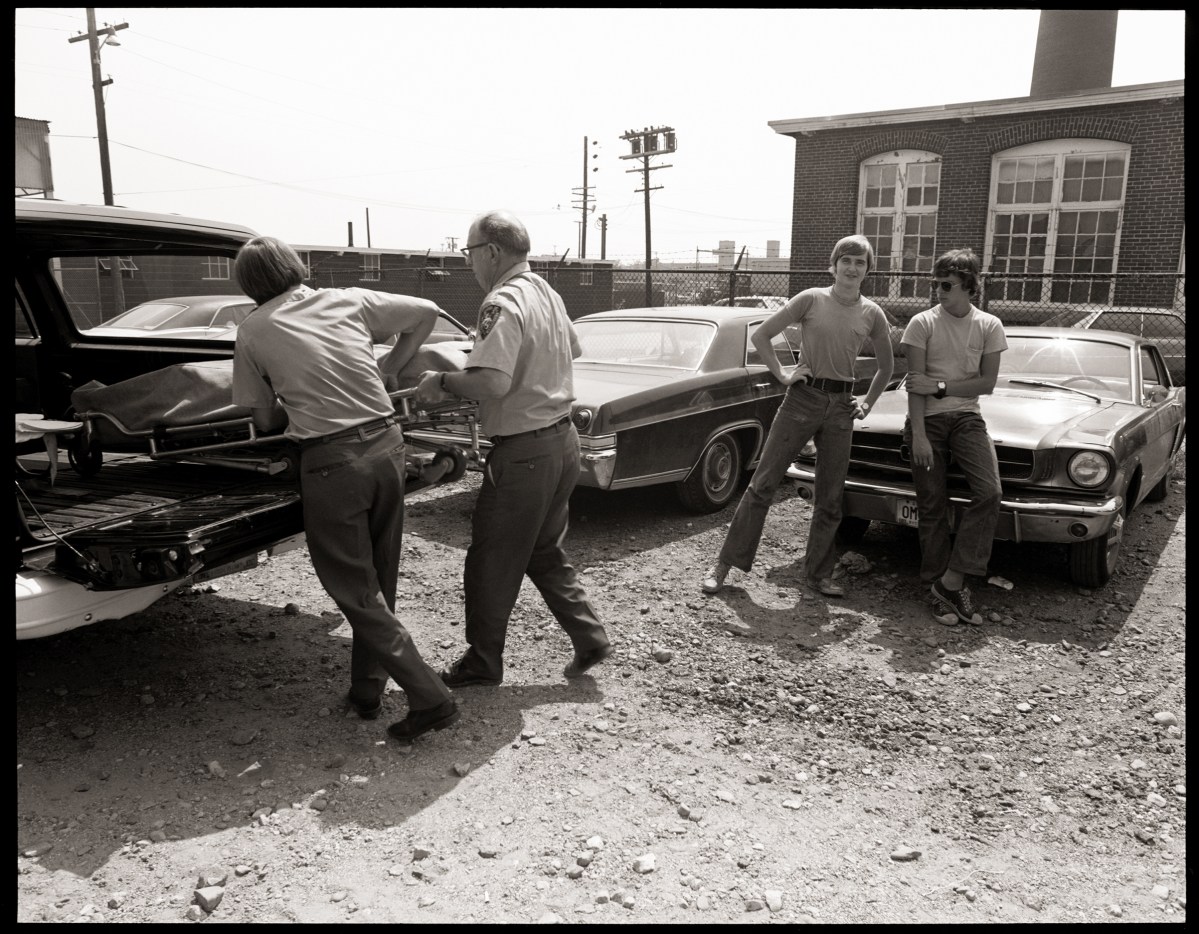

He went to the right place, for the morgue is where those who are murdered or die by accident or suicide are brought to be examined, probed and autopsied (autopsy, from the Greek word meaning “to see for oneself.”) In the morgue, these anonymous dead are exposed, so that they might be identified. In this way, the morgue is a perfect place to test the essence of photography.

Home death, silver slippers, 1973

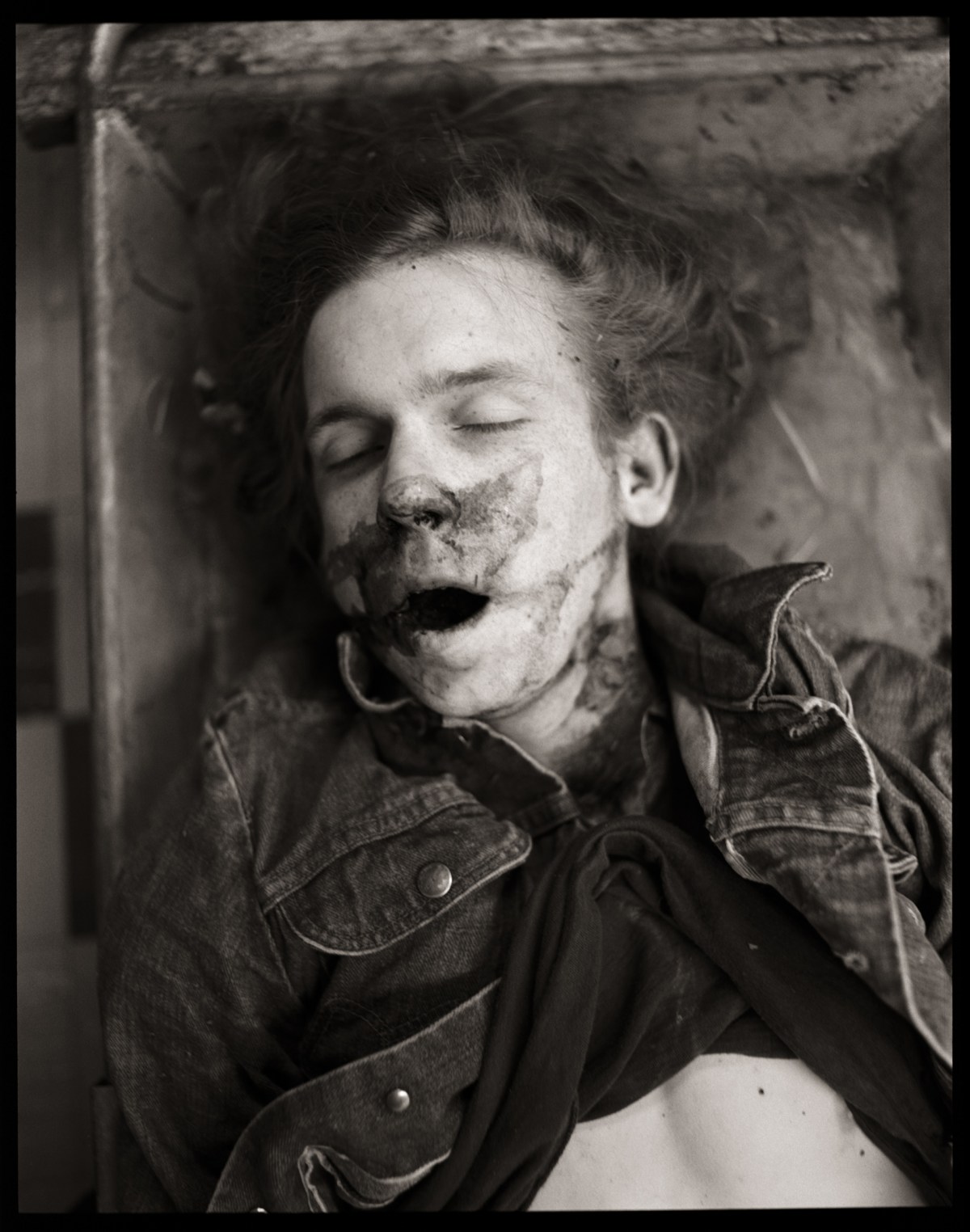

Boy found in bushes, 1973

Photography, as Walter Benjamin, Roland Barthes and many others have pointed out, has always had a special relationship to death. What appears in photographs is “what has been, and is no more.” All photographs of people fall into one of two categories: images of people who are dead, or images of people who will be dead. The best photographs are haunted by this inevitability.

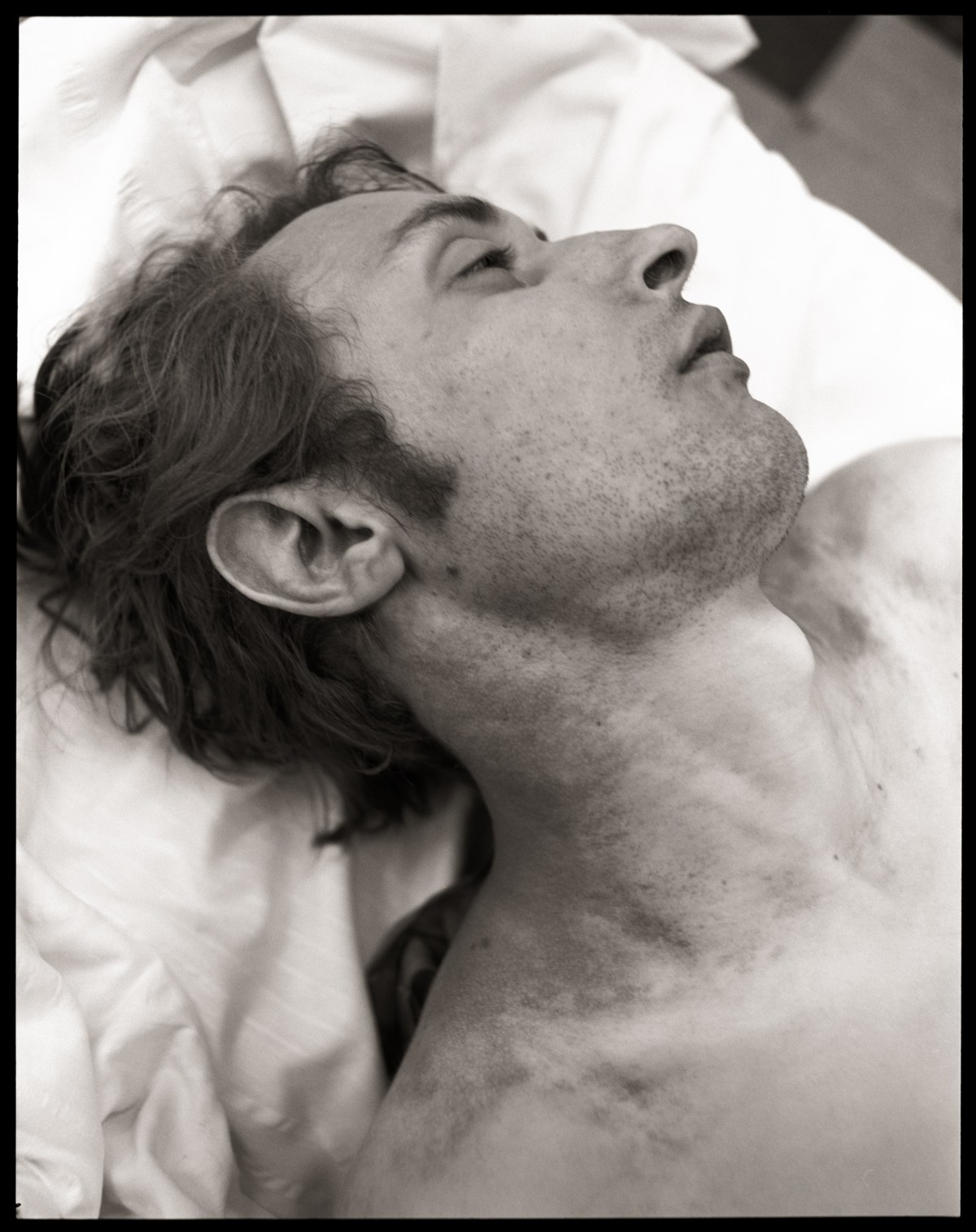

Silverthorne’s photographs from the morgue allow the dead a good deal of dignity, even in this coldly forensic setting. The dead bodies of babies, so recently inhabited, now empty of life, are lovingly treated, and a “Boy Found in Bushes” appears to sleep peacefully, despite the dried blood covering the lower half of his face. The boundary between life and death is blurred in these photographs, because that’s what photographs do: they present the surface of things in a way that triggers memories of wholeness, movement and life. As Silverthorne says, “The good photograph somehow retains the equivalent of the cadaver’s eye’s vitreous fluid, which stays true to the life well past the time of death, an ocular proof.”

Your reaction to this book of photographs will depend upon your beliefs about the sanctity of the body after death. Reactions may range from thinking it is a beautiful work of fellow feeling and compassion, to finding it offensive and brutal.

Crib Death, 1973

Crib Death, 1973

In contemporary American society, death is treated, for the most part, as an inconvenient truth—something to be fought against, shunned and denied. We believe we are entering an age of technological immortality, where death will be seen as an embarrassing anachronism, like photography.

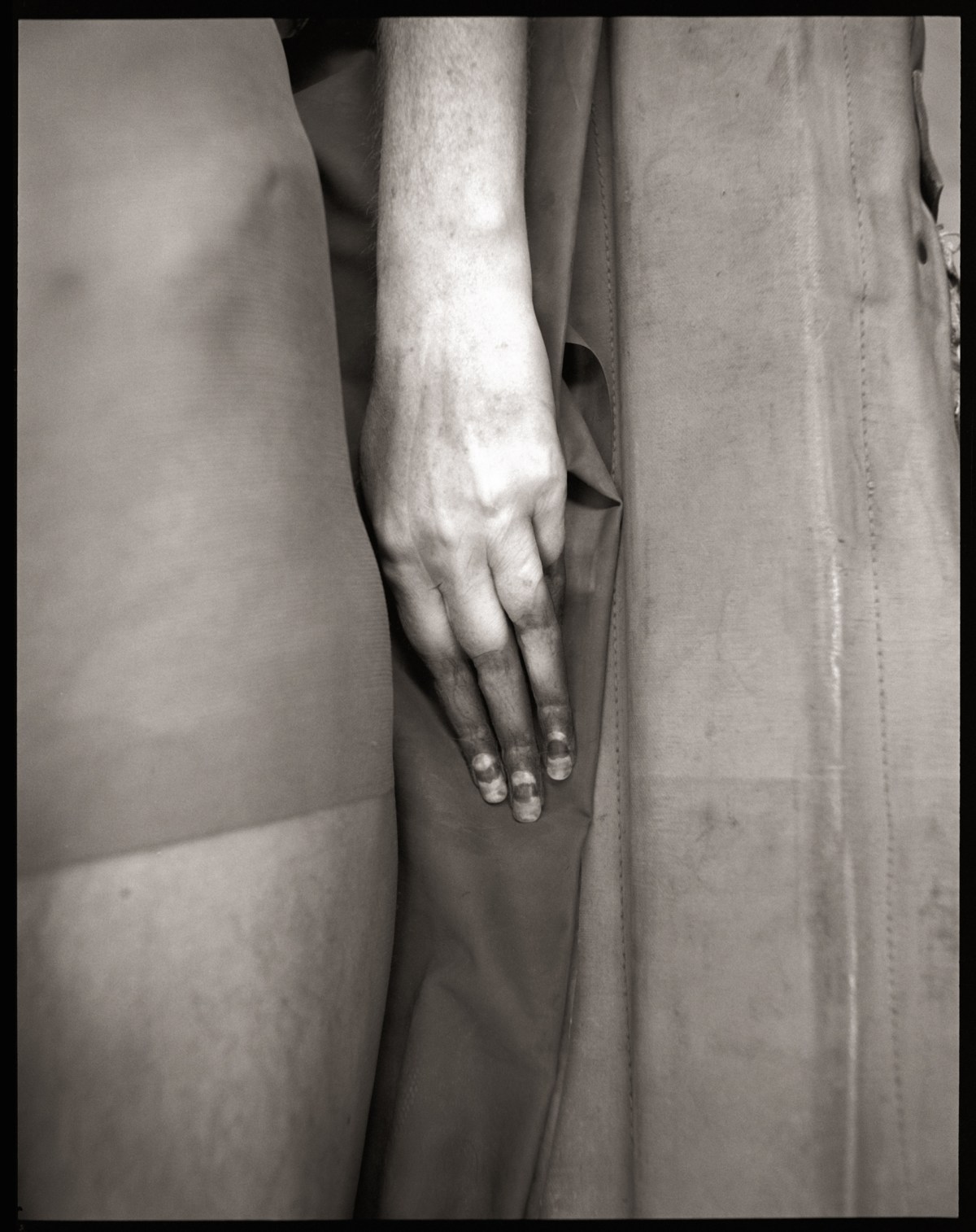

In the end, perhaps the mesmerizing proliferation of photographically derived images on social media today will have a larger purpose. “For Death must be somewhere in a society,” wrote Barthes. “If it is no longer (or less intensely) in religion, it must be elsewhere; perhaps in this image which produces Death while trying to preserve life.” Silverthorne’s images of a “Woman Who Died in Her Sleep,” gesturing in death as tenderly and convincingly as in life, to signal Morpheus and Thanatos, and of a baby’s intractable foot, and of two dead lovers in repose, asphyxiated, take the memento mori tradition to a new level of transparency—to try again to preserve and sanctify life by remembering how conditional and fleeting it is.

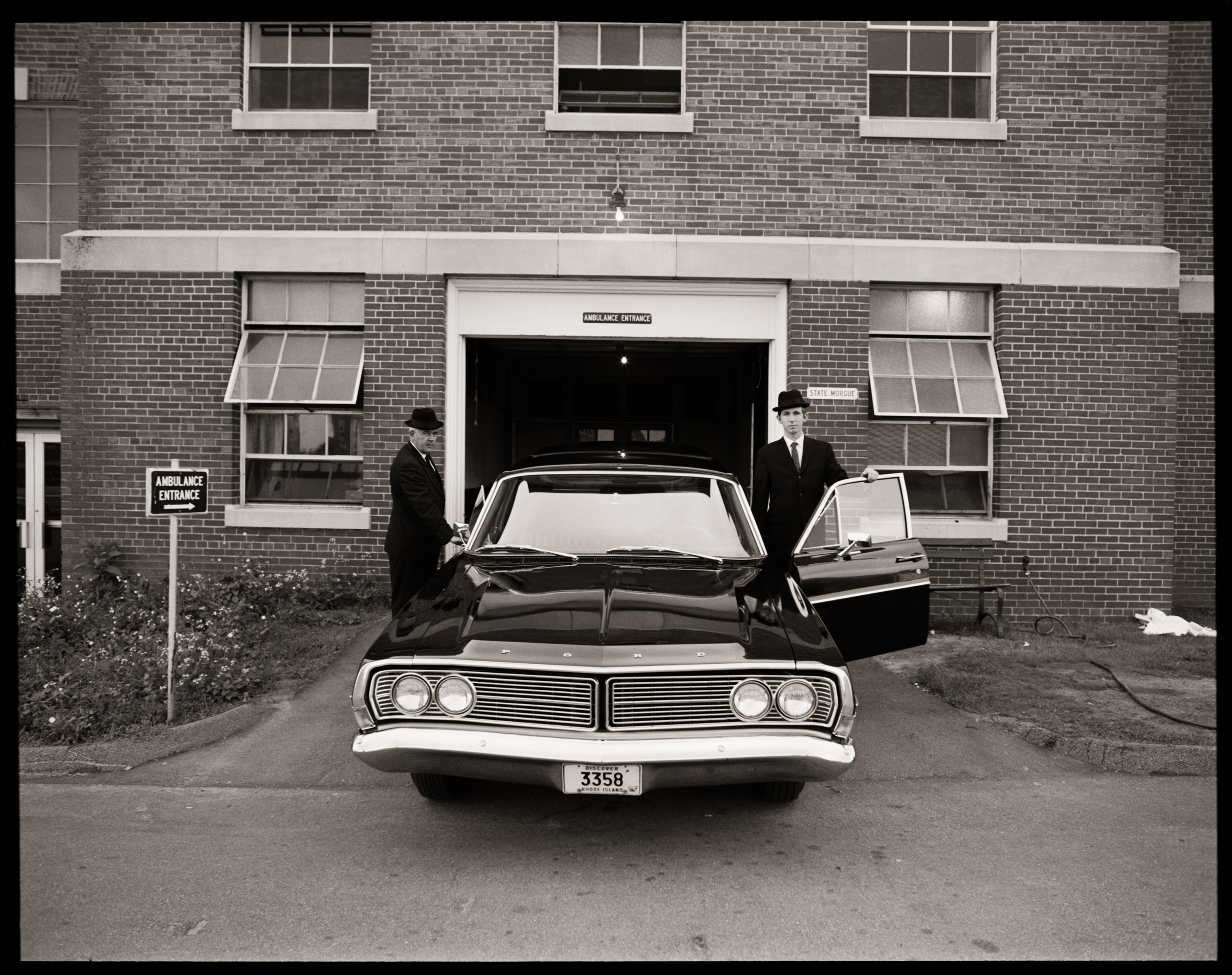

Police photographer and morgue workers, 1973

Unknown, 1973

Home Death, 1973

Heart Attack, 1973

Lovers, accidental carbon monoxide poisoning, 1973

Scott looks at Carol, 1973

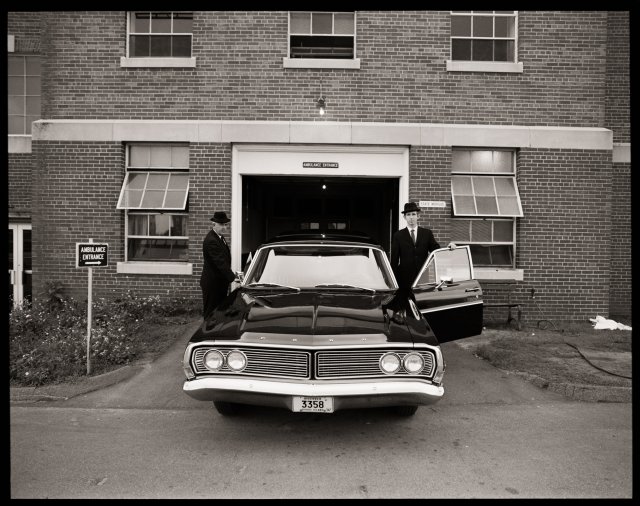

Pickup, 1973

David Levi Strauss is a poet, essayist, art and cultural critic, and educator living in New York.

Jeffrey Silverthorne is a photographer based in Rhode Island, and represented by the PDNB Gallery. Morgue is published by Stanley/Barker in London.