When Scott Kelly calls home from the International Space Station (ISS) sometime next year, whoever answers the phone may simply hang up on him. The calls will be welcome, but the link can be lousy, with long, hissing silences breaking up the conversation. That’s what happens when you’re placing your call from at least 229 mi. (369 km) above the Earth while zipping along at 17,500 m.p.h. (28,164 kph) and your signal has to get bounced from satellites to ground antennas to relay stations like an around-the-horn triple play. “When someone answers, I have to say, ‘It’s the space station! Don’t hang up!’” says Kelly.

When Scott Kelly calls home from the International Space Station (ISS) sometime next year, whoever answers the phone may simply hang up on him. The calls will be welcome, but the link can be lousy, with long, hissing silences breaking up the conversation. That’s what happens when you’re placing your call from at least 229 mi. (369 km) above the Earth while zipping along at 17,500 m.p.h. (28,164 kph) and your signal has to get bounced from satellites to ground antennas to relay stations like an around-the-horn triple play. “When someone answers, I have to say, ‘It’s the space station! Don’t hang up!’” says Kelly.

That’s not likely to be necessary when he calls his brother Mark. Perhaps best known as the husband of former Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords, who was grievously wounded in an assassination attempt in 2011, Mark is a former astronaut who has been to space four times. He knows the crackle of an extraterrestrial signal in his ear, just as he knows the singular feeling of weightlessness, the singular sweep of Earth outside the window—and the power of 229 miles of altitude to make a person feel alone. Drive that in the flat and it’s nothing more than Syracuse to Boston. Fly it straight up and it’s a whole other thing.

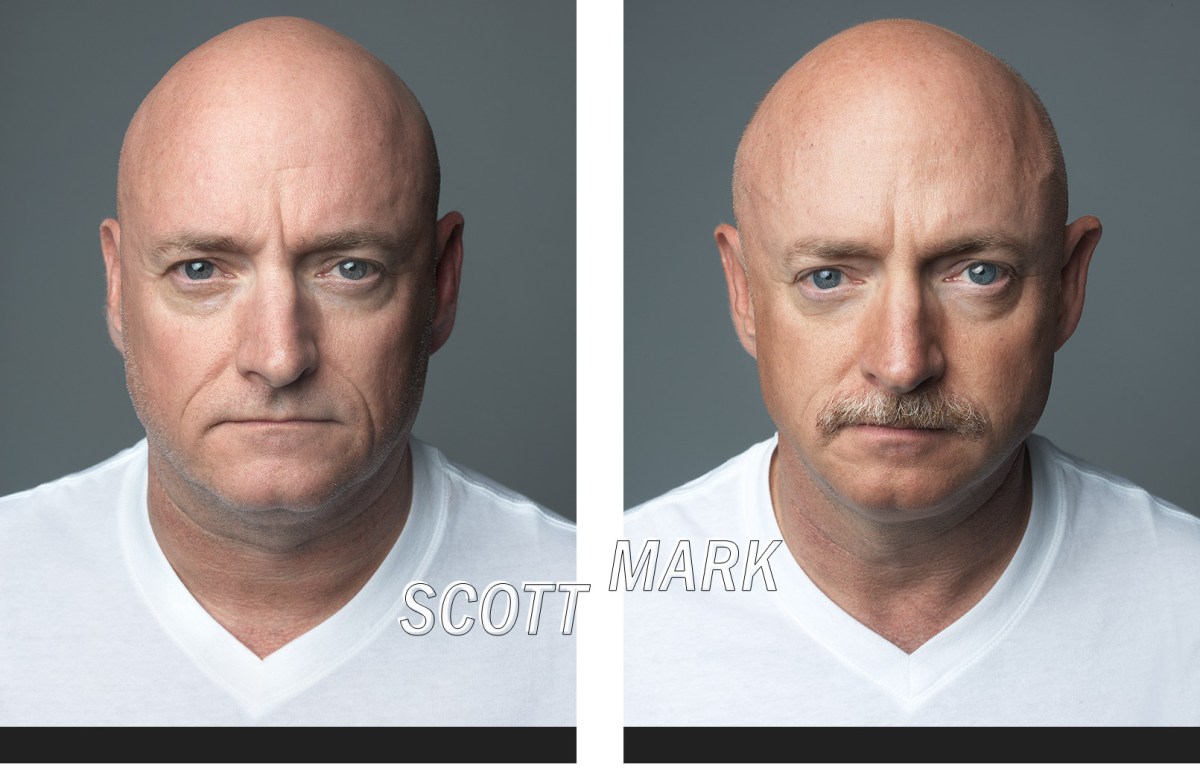

But most of all, Mark, 50, knows Scott, 50—which is how it is with brothers, especially when they’re identical twins, born factory-loaded with the exact same genetic operating system. The brothers’ connection will be more important than ever beginning in March, when Scott takes off for a one-year stay aboard the space station, setting a single-mission record for a U.S. astronaut.

Scott will be partnered in his marathon mission with Russian cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko. They, in turn, will be joined by a rotating cast of 13 other crew members, all of whom will be aboard for anywhere from 10 days to six months, conducting experiments and reconfiguring various station modules for the arrival of privately built crew vehicles, which could come early as 2017.

A year in space will require Scott to leave behind a lot: his Houston home, his daughters—Samantha, 20, and Charlotte, 11—and his girlfriend of five years, Amiko Kauderer, a NASA public-affairs officer. (He and his first wife are divorced.) But he won’t, in some ways, leave Mark behind.

Ever since the Apollo days, the U.S. has vaguely discussed a crewed mission to Mars, though the target date for the grand expedition has always remained a convenient decade or two away. But on Dec. 5, NASA took a big step toward that goal, with the successful uncrewed test flight of the Apollo-like Orion spacecraft—America’s deep-space ship of the future. Add to that the competition from upstarts like Elon Musk’s SpaceX and newbie nations like China and India, with their own surging space programs, and the scramble for cosmic supremacy is accelerating fast.

The biggest problem with our exploratory ambitions is, simply, us. The human body is a purpose-built machine, designed for the one-G environment of Earth. Take us into the zero-G of space or the 0.38 G of Mars and it all comes unsprung. Bones get brittle, eyeballs lose their shape, hearts beat less efficiently since they no longer have to pump against gravity, and balance goes awry. At least that’s what we know so far. “There’s quite a bit of data [on human health] for six months in orbit,” says space-station program manager Mike Suffredini. “But have we reached stasis at six months, or do things change at one year? Is there a knee in the curve we haven’t reached yet?”

So NASA needs subjects to venture out and run the long-duration tests. In a perfect experiment, every one of those subjects would also have a control subject on the ground—someone with, say, the exact same genes and a very similar temperament, so you could tease apart the changes that come from being aloft for 12 months from those that are a result of growing the same year older on Earth. In the Kelly brothers—and only the Kelly brothers—NASA has that two-person sample group. “The twins study didn’t come up when we were selecting crew for the mission,” says Suffredini. “But it occurred to us later that we had this ground-based truth in Mark.”

What NASA calls a “ground-based truth,” of course, Scott calls a big brother (by six minutes). And while the mission that is to come may be equal parts science experiment, endurance test and human drama, it is to the Kelly brothers (and only the Kelly brothers) just the latest mile in a journey they’ve shared for half a century.

Rocket Men

It’s a matter of historical record that Scott and Mark Kelly never got around to building an airplane. They never built a rocket ship either, but on both counts they can be forgiven. There’s rarely much follow-through when you’re 5 years old and you hatch your plans at night, in whispers, after your parents have put you to bed.

The brothers did their planning around the time of the Apollo 11 moon landing, when space travel seemed sublimely cool. They were alike in their fascination with space—and in other ways too. Like many twins, they spoke their own private language in toddlerhood, gibberish that was unintelligible to adults but seemed to make perfect sense to them. They dressed alike until first grade too. “There is a picture of us in orange shorts, orange striped shirts and bow ties,” Mark says—with a small wince. “We did everything together until college and were always on the edge of getting into trouble.”

By the late 1980s, both brothers were commissioned as naval aviators and both were assigned to active duty aboard aircraft carriers. Upon finishing their first squadron assignment and tour of duty, both became Navy test pilots. In 1995 they applied to NASA, and by 1996, they were dressing identically once again—and once again in orange—this time in the pressure suits of a space-shuttle astronaut.

From 1999, the brothers served a combined seven missions, though they never went to space together. (NASA had no policy against that, but Scott nixed the idea. “I thought it would really suck for our kids to lose both their dad and their uncle in one accident.”) And while they insist there has never been any competition between them, their interplay suggests a gentle tweaking all the same. “Scott flew first,” Mark says, “but I flew twice before he got his second flight. Then I flew my third before he did.”

Over drinks at Boondoggles, an astronaut haunt in Houston, Scott describes a stubborn eye twitch he experienced during re-entry after his last mission, a 159-day stay aboard the space station that ended in 2011. It’s something other long-duration astronauts have complained of too, but there is no explanation for it yet.

“What do you mean your eyes twitched?” Mark asks.

“Yours didn’t?” Scott responds.

“No.”

“Your flights weren’t long enough.”

By shuttle standards, Mark’s flights were actually pretty standard in terms of duration. His four trips ran about two weeks each, giving him a total of 54 days in space. Scott’s first two flights were similar, but his 159-day stay put him at a running total of 180, with a full year coming up next.

A Day in Orbit

As much of an adventure as Scott’s mission is likely to be, neither Mark nor anyone else would envy him every part of it. The ISS is spacious enough: from end to end, it measures 358 ft. (109 m), a little larger than a football field. The 14 modules that make up the living and work space represent only a small fraction of that overall sprawl, but together they provide as much habitable space as the interior of a 747—or, as the astronauts prefer to think of it, as much as a four-bedroom house.

Still, stay inside any house for a year—even one in orbit—and you’re going to fall into a routine. For all astronauts, a day aboard the station begins and ends in a private enclosure about the size of a phone booth that serves as sleep chamber and personal space, with enough room for a laptop computer, a few belongings and a sleeping bag. Reveille, in the form of an alarm from a wristwatch or an iPad in each astronaut’s enclosure, comes at about 6:30 a.m. (Greenwich mean time), but Scott admits that on his last flight he often hit the snooze button. “I wouldn’t wake up at the time it says on the schedule,” he says. “I’d generally get 30 extra minutes of sleep.”

When astronauts do crawl out of the sack, the day that unfolds usually follows a 30/40/30 work breakdown—30% of the time devoted to science experiments, 40% to physical exercise and monitoring the station’s systems and 30% to fixing hardware breakdowns—which is the way of things when your home requires 52 computers, 3.3 million lines of code, 8 miles (13 km) of wiring and 90 kW of power coming from an acre of solar panels just to keep operating.

The daily schedule does allow for some downtime. Movies and books are stocked in the station, and NASA can send up nearly any TV show the astronauts request. The crew members are free to email with family members whenever they want, call home when they’ve got a good downlink and surf the Internet—though the connection can be sluggish.

On this flight, the time for distractions may be especially tight, thanks to the battery of 10 medical and psychological tests that will be on the agenda for both Scott and Kornienko in orbit and for Mark on the ground. Flight surgeons will run studies of cardiovascular efficiency, blood-oxygen levels and blood volume. Bone density will be monitored, as well as cellular aging and fluid shifts in the body. Sonograms will be taken of the eye and optic nerve to determine how those shifts affect vision.

The body’s microbiome will come in for scrutiny as well. The bacteria that make their home in your gut are critical to maintaining bodily function, but everyone’s internal ecosystem is different, depending on diet and environment. The twins’ microbiomes will be regularly compared, via the unlovely business of analyzing body waste. “Giving urine and stool samples is an incredibly exciting thing to do,” Mark says drily. But in the service of human spaceflight—even when that service is secondhand—it’s worth the small indignity. “I miss every day I spent in space,” Mark readily admits.

Your Brain on Space Travel

If the body can suffer from long-term space flight, the mind is hit even harder—and that causes NASA particular concern. Psychologists will track Kornienko’s and Scott’s cognitive function, mood and stress level, partly with regular—and private—interviews. They will be especially alert for what is known as the third-quarter effect, a slacking off of psychological performance that hits between the half and three-quarter point of any long confinement or tour of duty.

“Scott has flown a six-month mission, so we have data on him,” says NASA psychologist Al Holland. “But it’s not a linear thing. Running a full marathon is different from running two half-marathons.”

Here, the science must yield a bit to the wild card of human emotion, and even a veteran like Scott may have trouble wrapping his mind around the scope of the mission he’s about to undertake. His flight begins on March 28, but he has to leave the U.S. on Feb. 16, since he will take off from the Russians’ Baikonur launch complex. Recently, Kauderer, his girlfriend, mused that since his birthday is Feb. 21, he’ll be 50 when he leaves the country and 52 when he comes home . “I was like, ‘Thanks for pointing that out,’” he laughs.

It’s easy to make jokes at T minus three months. Things will get harder in the spring, when the mission’s 5,920 orbits get under way. It is then that the brother in space will be especially fortunate to have the brother on the ground. “This is a dangerous job,” says Mark. “The public doesn’t understand how dangerous. But Scott can talk to someone who’s done this before.”

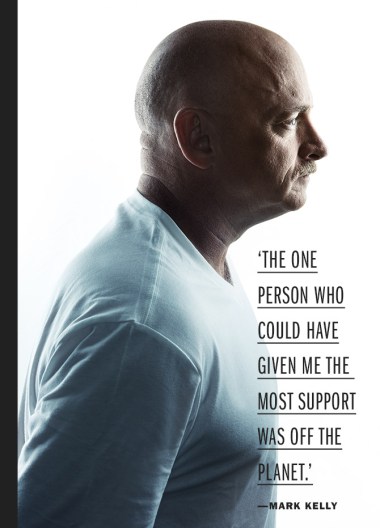

During Scott’s last mission, it was Mark who had to lean on him—in January 2011, when Giffords was shot. NASA got the news up to Scott, and it was only later that the brothers could talk. For Mark, it wasn’t quite the same. “The one person who could have given me the most support,” he says, “was off the planet.” This time, the support will likely come from the ground up.

Mark has already retired from NASA but is a consultant for SpaceX and has not given up thoughts of returning to space one day. Scott has not decided whether he’ll retire when he returns to Earth in 2016. Either way, it’s unlikely that the Kelly brothers, who once dreamed of building a rocket ship side by side, will ever fly in one together. But if humanity hopes to beat the biological limits that confine us to one small planet in a trackless universe, it will depend on the kind of science both brothers will soon make possible. Only one Kelly name will be on the mission patch, but to those who appreciate the brothers’ bond, it will stand for both.