The President's reelection campaign is in trouble. Will the turnaround plan work?

Last June, Barack Obama slipped into the White House to deliver a warning to Joe Biden. The state of Biden’s re-election campaign was shaky, Obama told him over a private lunch, according to a Democrat briefed about the meeting. Defeating Donald Trump would be harder in 2024. The mood of the country was sour. Persuading unhappy voters was going to be difficult. Biden needed to move more aggressively to make the race a referendum on Trump, Obama advised.

The former President left believing the current one had gotten the memo. But over the next six months, Obama saw few signs of improvement. In December, he returned to the White House at Biden’s invitation. This time, Obama’s message was more urgent. He expressed concern the re-election campaign was behind schedule in building out its field operations, and bottlenecked by Biden’s insistence on relying upon an insular group of advisers clustered in the West Wing, according to the same Democratic insider. Biden needed to get it together, or Trump would sweep the seven key battleground states in November, six of which Biden carried in 2020.

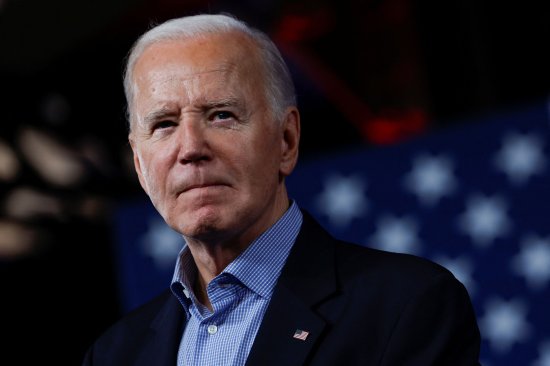

Three months later, the 2024 general election is under way, and Biden is indeed in trouble. His stubbornly low approval ratings have sunk into the high 30s, worse than those of any other recent President seeking re-election. He’s trailed or tied Trump in most head-to-head matchups for months. Voters express concerns about his policies, his leadership, his age, and his competency. The coalition that carried Biden to victory in 2020 has splintered; the Democrats’ historic advantage with Black, Latino, and Asian American voters has dwindled to lows not seen since the civil rights movement. Despite an attempted insurrection, 88 felony charges, and a record that prompts former aides to warn of the dangers of reinstalling him in office, Trump has never, in three campaigns for the presidency, been in as strong a position to win the White House as he is now. If the election were held tomorrow, more than 30 pollsters, strategists, and campaign veterans from both parties tell TIME, Biden would likely lose.

Read more: Why Biden’s Age Has Become a Bigger Deal Than Trump’s.

As a fog of dread descends on Democrats, Biden’s inner circle is defiantly sanguine. They see a candidate with a strong economy, a sizable cash advantage, and a record of accomplishments on infrastructure, climate change, industrial policy, and consumer protections that will register for more voters as the campaign ramps up. They see a pattern of Democrats overperforming their polling in recent years, from the 2022 midterms to a spate of special elections and abortion referendums. Most of all, they see a historically unpopular opponent. And in the end, they believe, voters dissatisfied with the President will tally the stakes—from reproductive rights to the prospect of mass immigration roundups to the future of U.S. democracy—and pull the lever for Biden again. “Our biggest strength is that 80 million people sent him to the White House before,” says Quentin Fulks, Biden’s principal deputy campaign manager, who notes that Trump needs to find new voters to win. “Our challenge is winning people who have already cast a ballot for Joe Biden and Kamala Harris once.”

Yet that may be a tall order in what’s shaping up to be a contest of which candidate America dislikes less. After a slow start, Biden’s campaign is charging forward, opening field offices, hiring staff, and launching an ad blitz painting Trump as a dangerous autocrat. But even if the President’s sputtering bid finds a new gear, allies say, the country is so bitterly divided that his ability to affect the outcome in November may be limited. Both sides are digging in for a gloomy slugfest, marked by depressed turnout and apocalyptic warnings about the fate that awaits the nation should the other guy win. Publicly, Biden’s brain trust is confident in their turnaround plan. Privately, even some White House insiders admit that they’re scared.

A lot has changed for Aidan Kohn-Murphy in four years, but at 20 years old, he looks the same as he did in 2020—a round smiling face beneath a mop of dark hair. Though he wasn’t old enough to vote in that election, Kohn-Murphy was the main organizer of #TikTokforBiden, the largest and most effective Gen Z social media campaign in support of the Democratic nominee. In the years since, #TikTokforBiden has transformed into the youth activist collective Gen Z for Change. And Kohn-Murphy has cooled on the President he worked tirelessly to elect.

It has nothing to do, as many assume, with the President’s age. With palpable frustration, Kohn-Murphy enumerates the list of perceived policy “betrayals” as though they were “tattooed on the back of my hand.” He’s upset about Biden’s inability to block construction of sections of Trump’s border wall. He’s upset about the Willow project, an oil-drilling operation that is proceeding on Alaska’s North Slope despite Biden’s campaign pledge to ban drilling on federal lands. And he’s upset about Biden’s sustained support of Israel amid its military campaign in Gaza, a position that has incensed legions of young progressives. In 2020, Biden clobbered Trump by 24 points with voters under 30. A New York Times/Siena poll conducted in December showed Biden trailing Trump by 6 points among the youngest cohort of voters, although subsequent polls have shown modest improvement. Gen Z voters “don’t understand why they should be compelled to cast their ballot for a candidate who has done so many things that are against their values,” says Kohn-Murphy. While he plans to cast a grudging vote for Biden, he’s worried that the threat of another Trump term won’t be enough to change the minds of his peers.

Read more: Young Progressive Activists Lay Out ‘Roadmap’ For Biden To Win Back Gen Z.

Young voters are not the only collapsing pillar of the party’s electoral coalition. Biden claims just 63% of Black voters, a sharp drop from the 87% he carried in 2020, according to polling by the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research at Cornell University. After winning Hispanic votes by a ratio of 2 to 1 four years ago, he now trails Trump among that voting bloc. Biden’s position on Israel amid the war in Gaza has tanked his standing with Muslim and Arab voters, particularly in must-win Michigan. Overall, Biden’s advantage over Trump among nonwhite Americans has shrunk from almost 50 points in 2020 to 12, according to the latest Times/Siena poll. “It boils down to voters of color, and those voters are pissed,” says one former Biden campaign and White House official, who, like others interviewed for this story, was granted anonymity to make candid appraisals about the President’s campaign. “I think it’s very likely he’ll lose.”

Incumbent Presidents are typically considered favorites for re-election, particularly those who have overseen a solid economy, as Biden has. Biden has a record to run on, beyond the bipartisan infrastructure bill and historic investment addressing climate change: billions of dollars of student-debt forgiveness; lowering drug costs; passing bipartisan gun-safety legislation; and much more. To some allies, there’s an obvious explanation for the gulf between the President’s performance and political predicament: a White House and campaign team tasked with selling his success have fumbled the job.

In the key battleground state of Arizona, for example, at least two major semiconductor plants are being built thanks to the CHIPS Act, historic legislation Biden signed to invest more than $52 billion in U.S. semiconductor manufacturing. Intel and Taiwan’s TSMC announced plans to create thousands of local tech and construction jobs, and the Greater Phoenix Economic Council estimates the investments will boost the regional economic output by billions. Yet only 25% of Arizona voters credit Biden for the new plants, according to polling from Noble Predictive Insights provided exclusively to TIME; 29% credit the companies, while 34% say they’re “not sure” who’s responsible.

Biden isn’t getting credit for his wins because his message has been too “academic,” argues Representative Bennie Thompson, the Mississippi Democrat who chaired the House select committee that investigated the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol. “So much of what’s been said is going over the heads of the average American citizen. It doesn’t need to be a dissertation. It just has to be a clear message. He’s going to have to work on that.”

Nearly two dozen senior Democratic sources tell TIME that Biden’s campaign mechanics, structure, and staffing over most of the past year are partly to blame as well. While Obama was marching to re-election over the summer of 2012, his campaign head count topped 900. Despite plans to hire 350 new staffers, the Biden campaign ended 2023 with only around 70 paid employees, according to campaign finance filings. His team says it is relying heavily on the network of staff that the Democratic National Committee has been bolstering for state races since 2021. (Trump also reported around 70 people on his campaign payroll, although that tally fails to account for the fact that much of his brain trust is spread across nominally independent super PACs and a think tank.)

As Biden defenders point out, bigger is not always better. “On the Kerry campaign, they had a Noah’s Ark—two of everything,” says a Democratic consultant involved in that losing 2004 team. Hillary Clinton’s ill-fated 2016 campaign had about 800 staffers, with an additional 400 at the Democratic National Committee and subsidies for almost 3,000 more within state parties. The overhead kept Clinton and her inner circle busy wooing donors rather than meeting with voters in crucial states.

Read more: How Biden Is Reviving His Midterm Playbook for 2024.

For the critical role of campaign manager, Biden installed Julie Chavez Rodriguez, a White House senior adviser, who has never before run even a statewide race. Biden was slow to dispatch the architects of his 2020 victory over to the current effort; in January, he finally reassigned top aides Jen O’Malley Dillon and Mike Donilon from the White House to the campaign after a delay that left top Democrats, including Obama, bewildered. But major strategy decisions are still routinely held up waiting for West Wing approval, a half dozen Democrats say.

The campaign has also been slow to build a field operation in key battlegrounds. In Georgia, a state he carried by fewer than 12,000 votes, Biden has one staffer. In North Carolina, where he came about 75,000 votes short of winning in 2020 and which now may present a pickup opportunity, the campaign has hired just three.

The result is a winnable race that risks being frittered away, some allies say. “This isn’t that complicated. Call [Pennsylvania Governor] Josh Shapiro, [Michigan Governor] Gretchen Whitmer. Ask them who should be hired and what 20 things need to be done to win those states,” laments a veteran Democratic consultant with experience guiding presidential nominees. “Don’t assume what worked last time will work this one.”

This complaint is echoed by scores of Democratic strategists, who see Biden as a politician captive to the past and content reprising a strategy that worked in the last election but looks increasingly ill-suited to the current one. “This is just who Joe Biden is,” says another top Democratic strategist who worked for Biden and has grown frustrated by the candidate’s reliance on longtime aides who deride outside critics. “This is how he’s always run his campaigns. He and his insiders know better. Last time, it worked, so he didn’t learn any of the lessons, and thinks he can run 2020 again.”

As Air Force One flew through turbulence on the way back from a March 9 campaign rally in Atlanta, Chavez Rodriguez was upbeat. Sitting in a high-backed leather chair, a blue Biden-Harris T-shirt peeking from under her gray blazer, Chavez Rodriguez rattled off the reasons for optimism. A big one is money. The Biden machine has built a formidable war chest, with $155 million on hand. Trump’s team hasn’t released comparable numbers yet, but his campaign and the Republican National Committee had about $40 million in January.

Chavez Rodriguez and her team viewed Biden’s fiery State of the Union speech as the starting gun of the campaign. Up next: a six-week, $30 million blitz of TV ads in battleground states that aim to define Trump as a threat to democracy and reproductive rights, while tackling the delicate issue of Biden’s age. The campaign has also begun rolling out its field operation; in addition to the new staffers, it plans to open 100 campaign offices in states like Arizona, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. “It’s about getting the boots on the ground,” Chavez Rodriguez says, “and building the ground game that we need to in all of our battleground states.”

A constellation of outside groups are also bringing cash and organizational clout to the fight. The 400,000-member-strong United Auto Workers has endorsed Biden, as have 18 other labor unions. At the Atlanta event, political action committees for Asian American, Black, and Latino voters—the AAPI Victory Fund, The Collective, and the Latino Victory Fund—together pledged $30 million toward boosting turnout for Biden. And a pro-Biden super PAC, Future Forward, has $250 million in fall advertising teed up in seven key states, which strategists say is the biggest single super PAC ad play in history.

The campaign is recruiting thousands of volunteers to connect with voters in their communities about Biden’s record, including through a digital platform called Mobilize.us that helps volunteers set up online events with friends. That multimillion-dollar push, which began in March, will run through the summer. In September, Fulks says, the campaign will shift gears to deliver supporters to the polls, employing everything from door-to-door canvassing to targeted social media, as well as the robust ground games of labor unions and abortion-rights groups.

Read more: The Inside Story of How Biden Cleared the Field for His Re-Election Bid.

The campaign is moving advertising dollars away from traditional broadcast channels and toward digital platforms like YouTube, Google search, Facebook, and online sports-streaming sites, where more voters spend their time, says Rob Flaherty, who oversees the campaign’s digital strategy. Despite Biden’s vowing to sign legislation that could ban TikTok if it doesn’t divest from Chinese ownership, his campaign joined the platform in February, churning out clips with titles like “4 insane policies in a 2nd Trump term” and “What is Trump saying lol.” As it works to court bold-faced names like Taylor Swift, Biden’s digital staff plans to tap local influencers in key voting districts who may have only a few thousand followers, but can carry the message to targeted communities.

When it comes to the President’s dismal numbers with young and nonwhite voters, the Biden brain trust recognizes the challenge but doesn’t share the panic of the party brass. To their mind, people who have cast a ballot for Biden before can be persuaded to do so again. “We’ve reached out to this group of nonwhite and young voters earlier than any presidential campaign ever has,” says senior adviser Becca Siegel. The campaign’s internal polling has found that young and minority voters have not tuned in to the election yet and haven’t thought about Trump in a while.

In the meantime, Biden’s team has devised strategies to engage key voting blocs in different ways. To reach Black voters in Georgia, the campaign plans to deploy surrogates like Senator Raphael Warnock, a pastor who preaches from Martin Luther King Jr.’s former pulpit, to juice turnout. Despite the sharp criticism of Biden coming from some voters of color, operatives predict Black voters in particular will stick with the President. “Black voters never loved Biden,” says Nsé Ufot, an organizer who helped deliver Georgia in 2020 by driving up Black turnout. “As the pragmatic political actors they have proven themselves to be, they will make the best decision based on the choices they have.”

Indeed, the biggest reason for optimism in Biden World may be the weakness of his opponent. As Election Day nears and Trump’s speeches and ideas garner the kind of attention they haven’t had since he left office, advisers expect fair-weather Biden supporters will remember how much they dislike his predecessor. “We know the work that we need to do to consolidate our base,” says the campaign’s communications director Michael Tyler. “The campaign is geared toward those efforts, while our opponent is still screaming into an echo chamber of MAGA extremism.”

The cornerstones of the case against Trump will be the dual threat he presents to democracy and reproductive rights. Since the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision, 21 states have stricter abortion restrictions than they had under Roe v. Wade. Democrats see an opportunity to pummel Trump on abortion access, as well as concerns about access to in vitro fertilization after the Alabama Supreme Court ruled that frozen embryos are legally children.

That push is designed to target women like Kelsey Lawrence, a 30-year-old mother of four living in Front Royal, Va. Lawrence thought of herself as having conservative and libertarian views before Dobbs. “I think every woman should have autonomy over her body,” Lawrence explained as she waited for Biden and Harris to take the stage at a January rally in the Northern Virginia exurb of Manassas. Democrats plan to continue tying unpopular abortion restrictions to the GOP; in January, the Biden campaign released an ad featuring a Texas doctor who was forced to leave the state to abort a nonviable pregnancy. In March, Harris became the first sitting Vice President to visit an abortion clinic.

The campaign is gaming out different paths to the 270 Electoral College votes it needs to win. One is to rebuild the Blue Wall, which includes the traditional Democratic strongholds of Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin, and then capture another toss-up state. A second route cuts through the Sun Belt—Nevada, Arizona, Georgia, and North Carolina. Democrats are pushing to add an abortion-access measure to the ballot in Arizona that they believe would drive up turnout for Biden. The same may be said for a polarizing GOP nominee for governor in North Carolina. Some Democrats aren’t ready to abandon hopes of Biden’s putting Trump’s current home state of Florida within reach. The paths to a win are varied enough that a major Democratic PAC is spending almost $4 million in the Omaha TV ad market, where Harris’ husband Second Gentleman Douglas Emhoff hosted political events in March in hopes of shaving off a single Electoral College vote in Nebraska’s Second District.

For all their meticulous planning, Biden’s team knows the race could hinge on factors outside their control. Four years ago this March, the sudden spread of COVID-19 in the U.S. shut down the economy and paralyzed the presidential campaigns. Without the pandemic, Trump could well have won. Any number of unpredictable events—the state of the war in the Middle East, foreign election interference, gas prices, persuasive AI-enabled deepfakes, the uncertain schedule of Trump’s trials—could shape the outcome to a greater degree than what the candidates do between now and November.

Allies are still hopeful for a more forceful performance from the President himself. It’s no secret that Biden, 81, is the oldest Commander in Chief in U.S. history, or that broad swaths of the country believe he’s no longer up to the job. The White House has tried everything it can—perhaps to a fault—to cosset him. Aides tend to avoid scheduling events in the early morning and evenings, limit his interviews and press conferences, and have him ascend the short stairs when boarding Air Force One to avoid any more embarrassing stumbles arising from his stiff gait.

But for Biden to beat the 77-year-old Trump, some allies believe it’s time to remove the bubble wrap. After campaigning successfully in 2020 on promises to restore the “soul of the nation,” Biden still clings to a self-image as a champion of comity. It is a pitch calibrated for an idealized electorate, not the one he has to win over. “People say, ‘I’m not going to vote for Trump, but I don’t know if I can vote for Biden.’ And everything they say has to do with his style: ‘He doesn’t seem to be fighting for us,’” says Representative Jim Clyburn, the former House Democratic whip, who has stepped away from his caucus leadership role to help Biden sharpen his message, urging the campaign to underscore the direct economic benefits of the Biden presidency.

Michael LaRosa, a former press secretary to First Lady Jill Biden, says the President has the capacity to author a comeback if he starts throwing punches. “He can talk about all of the accomplishments, Bureau of Labor Statistics, and economic-growth reports he wants,” LaRosa says. “Trump is talking about illegal migrants killing gorgeous young students jogging on campus, or the price of groceries, and placing the blame for both at Biden’s doorstep. Does he want to win the argument, or win the election?”

Recent flashes of fight have cheered the President’s supporters. After the boisterous State of the Union speech, he hit the road for a two-week swing through seven battleground states. The first event was at a middle-school gym in the Philadelphia suburbs, where Biden said Trump “got his wish” when the Supreme Court overturned Roe and states installed abortion restrictions. The President ticked through highlights of his record: limiting monthly insulin costs for seniors to $35; capping all Medicare prescription-drug costs at $2,000 a year; cutting credit-card late fees from $32 to $8; requiring corporations to pay a minimum of 15% in tax. When Biden called for an assault-weapons ban and stripping liability protections for gunmakers, the room erupted in cheers. After stepping off the stage, he shook hands and posed for selfies for 30 minutes, ignoring multiple announcements from his staff that it was time to leave.

When he finally did, the scene greeting him outside was a reminder of the challenge ahead. On the street in front of the school, dozens of pro-Palestinian protesters, holding signs reading Cease-Fire Now, erupted in chants of “Genocide Joe.” The protesters had camped there for hours as the sun set, waiting for their chance to get Biden’s attention. As his limousine pulled away, the crowd increased the volume of their chants, hoping the President would hear them from inside his armored car. —With reporting by Leslie Dickstein, Simmone Shah, and Julia Zorthian