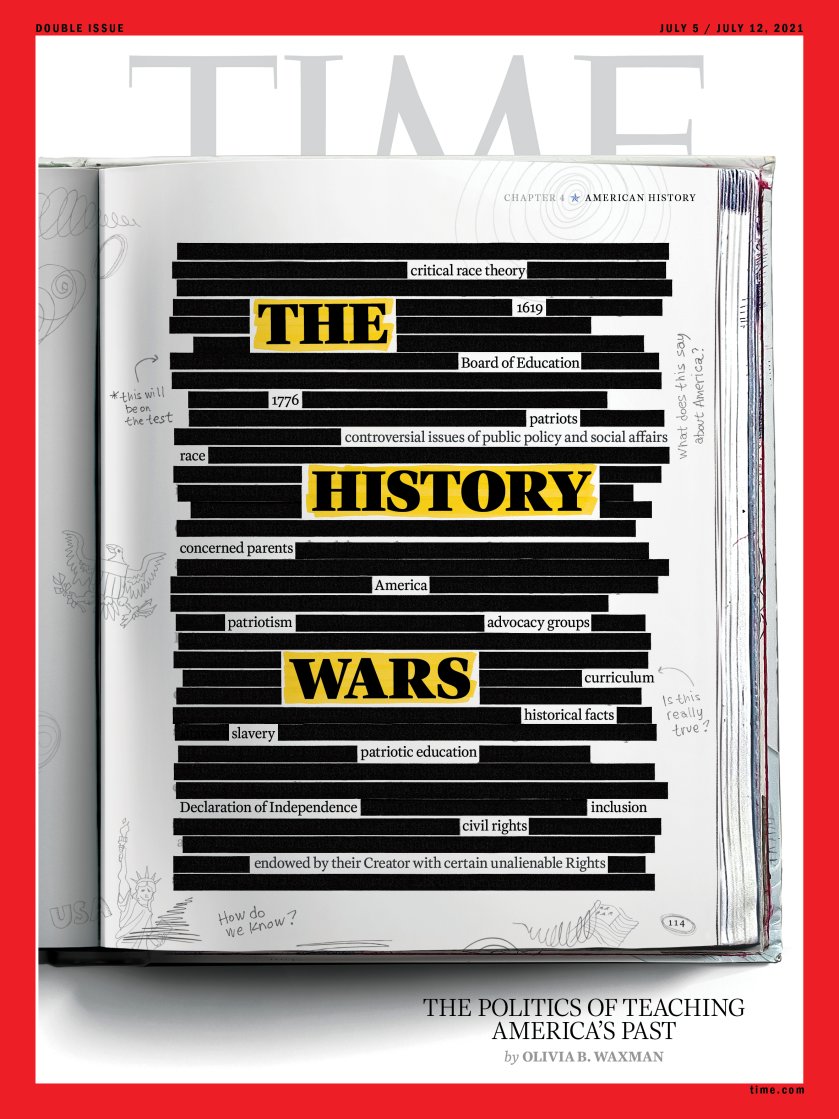

The national debate over how to teach the history of race in the U.S. is entangling local school boards and engulfing national politics

During the 15-minute observation period after receiving his COVID-19 shot this March, Terry Harris pulled out his phone. There in the Vashon High School gymnasium, during a vaccination drive for St. Louis–area teachers, the executive director of student services at the suburban Rockwood school district in Missouri noticed an email addressed to himself and district superintendent Mark Miles. The subject line stood out: “Protect your people.”

A parent had forwarded screenshots from a Facebook group called Concerned Parents of the Rockwood School District. Commenters called Harris, who is Black, “the most racist guy towards white people you’ll ever meet” and said he “has to be the one that goes first.” Harris saw a photo had been posted of him and his daughter, and the worst panic attack of his life began. “I tried to get up, and I stumbled,” he says. Sitting in his St. Louis living room 2½ months later, wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with the word LOVE, Harris, 39, recalls being so shaken that a National Guardsman came over to offer him water.

At a moment when Eastern European historians of the Holocaust are under threat from nationalist governments and countries with colonial pasts are pulling down statues and renaming streets, the debate over how to teach the history of race in America is entangling local school boards and engulfing national politics. It’s a conversation that predates the tumult of 2020: the New York Times’ 1619 Project, released to mark the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in Virginia, aimed to reframe America’s origin story around the legacy of slavery; the project helped push scholarly conversations about the impact of racism on U.S. history into the mainstream.

Buy a print of TIME’s cover for the “The History War” issue here

It has also galvanized those who worry applying that lens will teach children to hate America or divide the nation by emphasizing our differences. This viewpoint has come to the fore amid a surge of controversy over critical race theory (CRT), a decades-old academic framework that scholars use to interrogate how legal systems—as well as other elements of society—perpetuate racism and exclusion. Opponents of CRT now invoke it as a catchall term for any discussion of systemic racism. All of a sudden, this once obscure bit of pedagogy is the hottest topic in conservative politics. In recent weeks, Republican governors in Idaho, Iowa, Oklahoma, Tennessee and Texas have signed bills designed to restrict the way history is taught or ban the use of CRT. In a legally binding opinion, Montana’s attorney general called critical race theory and antiracism training “discriminatory” and illegal “in many instances.” On June 10, the Florida board of education approved a rule that instruction “may not define American history as something other than the creation of a new nation based largely on universal principles stated in the Declaration of Independence.” At least 25 states have proposed or taken actions designed to restrict how teachers discuss racism and sexism, according to Education Week. One group in Nevada is calling for teachers to wear body cameras; under a bill that was proposed in Arizona, teachers could have been fined $5,000 for teaching students to feel “guilt” over their race.

All this is no accident. Conservative advocacy groups, legal organizations and state legislatures have mounted a campaign to weaponize the teaching of critical race theory, driven by a belief that fighting it will be a winning electoral message. It’s hard to predict the issue’s potency at the ballot box. But a June Economist/YouGov poll showed that although only about a third of respondents had a good idea of what CRT was, most people who knew about it had an unfavorable opinion.

In short, “Make America Great Again” has evolved into “Teach America’s Great Again.” Candidates for local school boards, which tend to wield power over questions like which textbooks are used, are being grilled about where they stand on historical facts. Like nearly all controversies involving race in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, Americans are joining Team 1776 or Team 1619 along partisan lines. Last fall, the American Historical Association and Fairleigh Dickinson University, supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities, conducted a national survey on what Americans think about history. In preliminary results shared with TIME, they found that 70% of Democrats said the study of history should “question” the past, while 84% of Republican respondents said the goal was to celebrate it.

It’s a debate between people who think children shouldn’t be burdened with the past, and those who want kids to learn how the legacy of that past shapes American society today. Is our national history merely a tool to inspire patriotism, or is it, as historians argue, a valuable lesson in the good, the bad and the ugly? As this new front in the culture wars shows, our understanding of the past is a key factor in how we envision our future. This is a story about the story—and the myths—America tells about itself.

Like many communities where critical race theory has been a subject of fierce debate, the Rockwood school district does not even teach it. Actual critical race theory is rarely taught below the graduate level. Yet educators like Harris are under fire for their increasing efforts to ensure schools teach a more diverse curriculum, with an emphasis on equity. That afternoon in March, the school district filed a police report and looped in the FBI. A security guard was sent to Harris’ home and the nearby home of his colleague Brittany Hogan, who is also Black and served as the school district’s director of educational equity and diversity, a title created for the 2020–2021 academic year. The district has since filed three police reports because of social media posts concerning staff members; at least four staff members and one incoming assistant principal—all but one of whom are Black—have received threatening voice mails, emails or social media posts.

Harris is undaunted. “We have to talk about the fact that race and racism is real, and is as much of the fabric of America as apple pie or the Fourth of July or the Second Amendment,” he says. “Just because that’s where we are doesn’t mean that’s where we have to be.”

But not looking back is also an American tradition. “We have it in our power,” Thomas Paine wrote in his 1776 pamphlet Common Sense, “to begin the world over again.” In that spirit, New England towns perpetuated a myth that Native Americans had died out, as Native American historian Jean O’Brien has tracked. John Burk’s three-volume history of Virginia, published in the early 19th century, largely left out slavery. “There were no bigger revisionist historians than the founding generation themselves,” argues historian Michael Hattem, author of Past and Prologue: Politics and Memory in the American Revolution. Worried about children reading “long-legged Yankee lies” in textbooks written up North after the Civil War, the United Daughters of the Confederacy played a key role in propagating the “Lost Cause” myth that the South fought nobly for states’ rights, not for slavery.

As history education in American K-12 schools was formalized in the late 19th century, during a period of nativism and nostalgia, the idea that such classes should inspire patriotism became more widespread. During World War I, a New York State law banned public schools from using textbooks containing material “disloyal to the United States.” In the 1920s, during a rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan, Oregon barred public schools from teaching from any textbook that “speaks slightingly of the founders of the republic.” Amid heightened fears of communism in the 1930s and 1950s, some states required teachers to take loyalty oaths. “There’s always a connection between the flare-up of conservative anger or fear of what’s going on in schools and larger political unrest,” says historian Natalia Mehlman Petrzela, author of Classroom Wars: Language, Sex, and the Making of Modern Political Culture.

Since the Supreme Court ruled in 1962 that mandatory school prayer is unconstitutional, the battle has only intensified, thanks in large part to conservative activists who worry public schools are a breeding ground for societal change. In 1969, California Governor Ronald Reagan’s moral-guidelines committee warned that people who conduct “sensitivity training” are “aligned with revolutionary groups” that “intend to use the schools to destroy American culture and traditions.” The roar grew louder as school integration programs ramped up in the 1970s, and continued into the 21st century through fights over everything from Title IX and Common Core to bathroom bills and COVID-19 closures.

“You can trace a decades-long agenda on the part of conservative think tanks to undermine public education whether via vouchers or charter schools or attacks on teacher unions,” says Sumi Cho, director of strategic initiatives at the African American Policy Forum, who taught critical race theory for over 25 years at DePaul University College of Law. “Critical race theory is simply the latest bogeyman.”

But the latest round of the battle does contain a new element: Donald Trump. On Constitution Day last September, the then President announced at the Library of Congress that he was creating a “1776 Commission” to “promote patriotic education.”

Trump sensed an issue gaining steam on the right. His announcement followed a Sept. 1 Tucker Carlson Tonight appearance by Christopher Rufo, 36, now a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, who is credited with catalyzing much of the uproar. Rufo began last summer to openly make the case that inclusion efforts at publicly funded institutions were going too far by teaching participants to apply what he called “critical race theory” to their lives. After that appearance on Carlson’s show, Rufo says, Trump’s chief of staff, Mark Meadows, reached out to talk. Soon the Trump Administration banned the use of CRT in federal offices. The President’s Advisory 1776 Commission came right after, and the movement against CRT began to expand its focus beyond corporate diversity trainings and into the classroom.

Released on Martin Luther King Jr. Day this year—Trump’s penultimate day in office—the 1776 Commission’s report did not have any power to compel school districts to do anything. Nor was it especially concerned with historical accuracy; an American Historical Association statement signed by 47 academic organizations condemned it as “a simplistic interpretation that relies on falsehoods, inaccuracies, omissions, and misleading statements” and “a screed against a half-century of historical scholarship.” But the document was an early peek at how the right would attempt to rally its base on the subject. It called for focusing classroom discussions of the U.S. founding era on the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, and not on “fashionable ideologies” like “claims of systemic racism” that threaten national unity.

The 1776 Commission was short-lived. One of President Joe Biden’s first acts on Inauguration Day was to terminate it. The move only spurred conservatives on. “By abolishing the commission, I think that actually helped the contribution of this report because it brought attention to it,” says Matthew Spalding, the 1776 Commission’s executive director.

Less than 12 hours after Trump left office, Rufo announced he had company in his quest. “The conservative legal movement and a network of private attorneys are gearing up for war against critical race theory,” he tweeted. “We will fight and we will win.”

Adam Waldeck was one of the people who saw Biden’s decision to nix the 1776 Commission as “a major slap in the face.” Waldeck, a 36-year-old former South Carolina state director and coalitions director for Newt Gingrich, works for a new issue-advocacy group called 1776 Action. It grew out of a conservative organization called the American Legacy Center, affiliated with Ben Carson, Trump’s former Secretary of Housing and Urban Development. “We as conservatives are losing perhaps the most fundamental cultural battle in our nation,” Carson wrote in a March 15 email to conservative donors and activists. “In classrooms in all 50 states, our kids and grandkids are the victims of a coordinated attack on our history, our heroes, and our very inheritance.”

On April 6, the group released an online video and paid radio ad supporting a New Hampshire house bill prohibiting the teaching of “divisive concepts” in schools. “Last year, radicals destroyed statues and burned cities. Now in many New Hampshire schools they’re brainwashing our children to hate America and each other,” the narration intones. Aspects of the bill became part of the proposed New Hampshire budget, which as of June 23 says teachers can’t instruct students that anyone’s identity makes them inherently oppressive, even unconsciously, although they are welcome to teach the “historical existence” of that idea. (Foes of such a rule might argue that while identity does not determine whether an individual is biased, it’s important for kids to understand how some groups as a whole benefit from discriminatory systems that are very much alive and well.)

The group also launched “The 1776 Pledge to Save Our Schools,” asking candidates for office to vow to “restore honest, patriotic education that cultivates in our children a profound love for our country.” Just as Grover Norquist’s Taxpayer Protection Pledge has shaped conservative doctrine for decades, Waldeck hopes the oath will become a litmus test for political hopefuls. (South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem, who is running for re-election in 2022 and viewed as a potential presidential candidate, has announced that she backs it.) But Waldeck, who is white, also envisions a society in which 1619 vs. 1776 becomes a political issue as fundamental as gun or abortion rights. “We want it to be something that ultimately people vote on,” he says.

On April 19, a public-comment period opened for an Education Department proposal that would prioritize grant funding to American History and Civics Education projects that incorporate diversity and inclusion, including curriculums that “take into account systemic marginalization, biases, inequities, and discriminatory policy and practice in American history.” This relatively obscure proposal sparked a national conflagration. In Washington, D.C., Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell spoke out against it. In Idaho, on April 28, GOP governor Brad Little signed a bill designed to deter schools from applying for the grants. The next month, Idaho’s Republican lieutenant governor Janice McGeachin announced her run for governor in 2022, after launching a “Task Force to Examine Indoctrination in Idaho Education Based on Critical Race Theory, Socialism, Communism, and Marxism.”

Even the anti-CRT bills that have failed have served a purpose, authors say. “I think the ultimate success is making parents aware that this is something that is not just taking place on the West Coast or the East Coast,” says Arkansas state Representative Mark Lowery, who introduced two bills to restrict curriculums in the state. He ended up withdrawing both, but still counts them as a PR win. “It’s actually coming to your local school district.”

The Concerned Parents of the Rockwood school district were swept up in this trend. Like many others worried about critical race theory, Rockwood parents reached out to two of the main organizations trying to mobilize families nationwide to speak out about diversity initiatives in school: the Foundation Against Intolerance & Racism (FAIR) and Parents Defending Education, both of which formed in January and launched publicly in March.

Parents Defending Education invites people to anonymously submit material they find concerning, says Erika Sanzi, its director of outreach—links to slide decks from teacher trainings; screenshots of assignments; emails that suggest “activism in the classroom.” The group then uses the tip line to file complaints with the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights, as it did based on one school district’s invite to a Zoom meeting that was described, in the aftermath of the March 16 shootings at Atlanta-area spas, as “a safe space for our Asian/Asian-American and Students of Color, *not* for students who identify only as White.” (The invitation noted that white students could still talk to the event’s organizers.) Sanzi said the group has been “bombarded” with submissions.

Nicole Neily, the group’s founder, says the goal is not to keep certain topics out of the classroom, but rather to change the way the conversation takes place. “I’m a libertarian; the word ban gives me hives,” Neily says. But her grandparents met in a Japanese-American incarceration camp, she adds, and she is sensitive to exercises that emphasize the differences between people. “It’s when we start to separate kids and make them feel bad and write down all the different ways that you have privilege—you’re straight, you’re white, you’re female,” she says. “To me, that’s compelling speech, and you’re treating children differently. It’s the implementation that concerns me, not the actual content of the lesson.”

FAIR, meanwhile, says it has more than 40 chapters nationwide, including one in the St. Louis area. “I don’t think it’s the school’s place to teach our children to be race-conscious,” explains FAIR co-founder Bion Bartning.

Both FAIR and Parents Defending Education are structuring themselves as a type of nonprofit that is not required to publicly disclose its donors. Because they were formed only recently, there are no tax returns available. But an analysis of public documents does provide some insight into the power behind the scenes. Former Fox News host Megyn Kelly, who has blasted her kids’ elite Manhattan schools as “far left,” and Alexander Lloyd, a venture capitalist and Republican donor, sit with Rufo on FAIR’s board of advisers. Neily, the founder of Parents Defending Education, is a former staffer at the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank co-founded by prominent Republican donor Charles Koch, and the president of Speech First, a nonprofit organization that supports free speech on campus through litigation and advocacy. Two of that group’s highest-paid independent contractors in 2018, according to tax filings, were Consovoy McCarthy, whose founding partner, William Consovoy, was Trump’s attorney, and CRC Public Relations, a well-connected advocate for conservative causes.

The former President is still in on the action too. In a June 18 op-ed on RealClearPolitics, Trump called for a 1776 Commission in every state, the establishment of a patriotic-education corps à la Teach for America, and a voucher program to move kids out of schools teaching CRT.

These tactics mark a new chapter in the culture wars over education, experts say. “Conservative activists have always worried that innocent white American children might be harmed by a traumatic exposure to ideas about race, class and American exceptionalism,” explains historian Adam Laats, author of The Other School Reformers: Conservative Activism in American Education. “But in the 20th century they did not accuse progressives of teaching racist ideas.”

They haven’t really needed to. For more than a century, patriotic education has largely prevailed. Students, for the most part, do not get an in-depth history of systemic racism unless they go to college. According to research by the Southern Poverty Law Center, only 8% of high school seniors in 2018 could identify slavery as the primary cause of the Civil War. While some educators do teach the topic in innovative or controversial ways, they are not the majority—although that may be changing, as social media enables the sharing of resources to help teachers field questions from students who are watching the news.

Ibram X. Kendi, author of How to Be an Antiracist, finds the idea that classroom explorations of racism are divisive to be ironic. “If we’re not teaching students that the reason why racial inequity exists is because of racism, then what are they going to conclude as to why racial inequity exists? They’re going to conclude that it must be because those Black people must have less because they are less,” Kendi says. “That’s the only other conclusion. Not teaching our kids about racism is actually divisive.”

Rockwood was ripe for a culture clash. It’s suburban and 75% white, with some of the best public schools in Missouri. While most of the district is in St. Louis County, which voted overwhelmingly for Biden, it also includes parts of Jefferson County, which voted overwhelmingly for Trump. Nearby St. Louis regularly appears on lists of the most segregated cities in America, and Rockwood is the largest participant in the area’s school-integration busing program, which is in the process of being phased out.

Lauren Pickett, 18, just graduated from Rockwood’s Marquette High School and covered the school’s diversity curriculum for the student newspaper over the past year. She says local divisions began to bubble up into conflict during Black Lives Matter protests last summer, which is when she perceived an unwillingness among white residents to hear about Black people’s negative experiences with police. “It’s actually more divisive to not want to be aware of anyone else’s history that’s different from your own,” says Pickett, who is Black. “I was very afraid when I first heard about legislation trying to ban teaching on critical race theory and take away teaching on slavery and racism, because it seems as though it’s erasing who I am and my history.”

When the Concerned Parents of the Rockwood School District Facebook group formed in July 2020 to discuss COVID-19 safety protocols, its members were at first an ideologically mixed group. But the tenor turned to the right, especially after Trump lost the 2020 election. The same forces that split citizens who were for and against masks split those for and against the idea of CRT being taught in schools—regardless of whether it was actually happening.

When Shauna Poggio saw the chatter on Facebook about a bill in Missouri’s legislature that would ban the 1619 Project, the 46-year-old school psychologist decided it was time to speak up. Her ninth-grade son, who attends Lafayette High School in Wildwood, Mo., had started complaining about discussions of cultural identity in his English Language Arts class. Poggio shared with TIME photos of a homework exercise that asked him to think about “assumptions that people make about people in the different groups you belong to.” (In the assignment, Poggio’s son described himself as being a white Republican who plays golf, and said people on the “far left” would probably assume that he is racist.) Poggio had heard about CRT in the news—she listens to Tucker Carlson’s podcast—but it hadn’t seemed relevant to her. Now, however, she was on alert.

On April 18, Poggio became one of at least a dozen Rockwood parents to submit a public comment in support of a 1619 Project ban, arguing that “this ideology has already infiltrated our district and created immense racial and political division.” Twelve days later, she attended an info session on CRT held at Brookdale Farms, an events venue with a back the blue sign at the entrance. It was organized by Kenneth Rosa, a local activist associated with the Fathers’ Rights Movement, an organization that advocates against systems the group sees as privileging mothers over fathers. Although some present spoke in favor of a curriculum that emphasizes inclusivity, a video went viral of a choked-up mother saying that “just because I do not want critical race theory taught to my children in school does not mean that I’m a racist, dammit.” (It’s racked up nearly a million views on Twitter since it was posted May 1.)

“My understanding of critical race theory is it kind of comes down to, ‘White people founded this country for slavery, and they’re the oppressors,’” Poggio says of her takeaway from that meeting. “‘And if you’re Black, then you’re oppressed, you’re the victim,’ and it kind of just leaves everybody stuck in that place where that’s the end of the story.” Poggio starts to tear up as she considers that kids aren’t learning about the national ideals that her grandfathers fought for in World War II. “I just think it disregards the idea that all people are created equal and in the image of God, and we can make our own destiny.”

The 1619 Project draws attention to how white veterans of World War II got to buy homes under the GI Bill while many of their Black counterparts were denied the opportunity to do so—a fact that has contributed to the persistence of the racial wealth gap today. But Poggio says she believes it’s more important to focus on teaching children that while injustice does linger—for people of all races—in America it’s still possible to overcome obstacles if you work hard.

As the spring dragged on, the district grew further embroiled in a war that went beyond group texts and Facebook comments. In the local school-board race in April, candidate Jackie Koerner got multiple emails asking her where she stood on CRT. (Incumbent candidates, who were not anti-CRT, won by a slim margin.) An April 22 email from a district literacy speech coordinator, Natalie Fallert, who is white, advised teachers how to avoid drawing the attention of parents hunting for “CRT” materials. It was leaked to the conservative news site the Daily Wire. About a month later, Fallert, who no longer works for the district, received a death threat calling her “anti-American.” Terry Harris, the administrator who had received the warning back in March, began switching up his work schedule as a safety precaution.

At one meeting, a white parent of three boys who attend Rockwood schools called critical race theory “psychological child abuse.” Another white parent read a letter from her daughter, a senior at Eureka High School, calling for an updated history curriculum that is “not just the dramatization of white people’s successes,” calling it “tragic” that she had to wait until AP U.S. History “to learn the truth.” When the school board met on May 6, a group of parents stood outside, holding signs thanking teachers for their diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) work. Joel Vanderheyden, 40, held one that said Understanding inequity is necessary to create equity. Diversity issues in schools had never been something he paid much attention to before, but now he was glued to school-board-candidate debates. “I’ve never voted in a school-board election in my life until this year because there wasn’t the urgency,” he says. Next year, Vanderheyden will be the co-coordinator of DEI at his son’s elementary school.

On the very last day of the school year, a confrontation took place in the Eureka High School cafeteria. Some students had come with Trump and “thin blue line” flags; others had rainbow ones to celebrate Pride Month. The two groups began the morning merely displaying their allegiances, but before long the standoff morphed into something more confrontational. By the end of the day, Eureka High’s assistant principal George Calhoun, who is Black, was receiving threatening voice mails falsely accusing him of confiscating an American flag, the district said.

While Concerned Parents of Rockwood represents those who think efforts to make the curriculum more inclusive have gone overboard, parents in groups like Rockwood REAL, Rockwood Ahead and MO Equity Education Support Group believe inclusive curriculum initiatives are exactly what’s necessary for their kids to understand American society. Shemia Reese, 39, one of the leaders of Rockwood REAL, grew up being bused into a nearby school district in the 1990s, and now her own kids are as well. She’s fed up with how much hasn’t changed since then. Her kids still tell her that they hear the N word at school. “As a parent, I’m doing the best that I can to make sure that they get the best education, and statistics show that Rockwood is where the best education is in Missouri,” she says. “As adults, if we can’t have these hard conversations, how can we possibly expect our children to?”

On the first weekend of June, Rockwood parents gathered at the Pillar Foundation in Ellisville, Mo., for a meeting called “Critical Race Theory Exposed.” Before the presentation, attendees took copies of handouts telling them they could identify CRT by the use of terms like racial justice and disrupt, and directing them to a site for Rufo’s anti-CRT outreach efforts.

The event’s organizer, Bev Ehlen, the state director for the Concerned Women for America of Missouri, opened with a prayer for the U.S. to turn back to God. Then, during a presentation that stretched over two hours, Mary Byrne of the Heartland Institute, a major conservative think tank that opposed Common Core, told more than 100 attendees that diversity trainings in educational settings are “iterations from Maoist struggle sessions” and that Black Lives Matter was a form of “Marxist indoctrination.” (There is a long history of smearing Black civil rights activists as communists.) “There are very few people who are honest about history,” Byrne said.

“Think of the public-school system as the Titanic going to hit an iceberg,” Zina Hackworth, 56, who is Black, shouted out as the presentation ended. “Get your children off of the Titanic!”

Amy Svolopoulos, 44, of Ballwin, Mo., sat in the front row, too overwhelmed to take notes. A white parent of three, she went into the meeting believing there should be nothing controversial about the idea that Black Lives Matter. She began crying at the end as she shared her worries that people with ulterior motives are using BLM to “deceive” kids. Now she is worried, she says, that critical race theory will “divide our youth instead of unite them.”

Not everyone had the same takeaway. Amy Ryan, 44, who was adopted from South Korea into a white family and experienced anti-Asian racism growing up in Indiana, watched from the back. What she heard, she said, reflected white Americans’ “fear that they are going to be treated how people treat marginalized groups.” After going to countless school-board meetings and community forums this year, Ryan wants to run for state office “to help slow down the madness that we’re in right now.”

Terry Harris remains optimistic that a divided Rockwood can come together. “I think the next steps are to really figure out where we are as a district, almost like, let’s do an equity audit,” he says. “How comfortable are you talking about some of these tough situations?” The students often have a better grasp of the stakes than their parents, he notes. They may not agree on everything, but they want to know the truth about how the U.S. got to where it is today.

When the students return in the fall, ready to hear America’s story again, superintendent Miles won’t be with them. He’s resigning after just two years in the job, citing the impact of the parent uprising over critical race theory on top of running a school district during a global pandemic. “I’m concerned as a fellow citizen that some have lost the ability to truly consider the perspective of another,” the 50-year-old former social-studies teacher says. “That is the mark of an educated citizenry.” —With reporting by Alana Abramson/Washington, D.C., and Alejandro de la Garza/New York

Correction, July 16

The original version of this story misstated whether government-registered nonprofits are not required to publicly disclose their donors. Some types of nonprofit groups must do so.