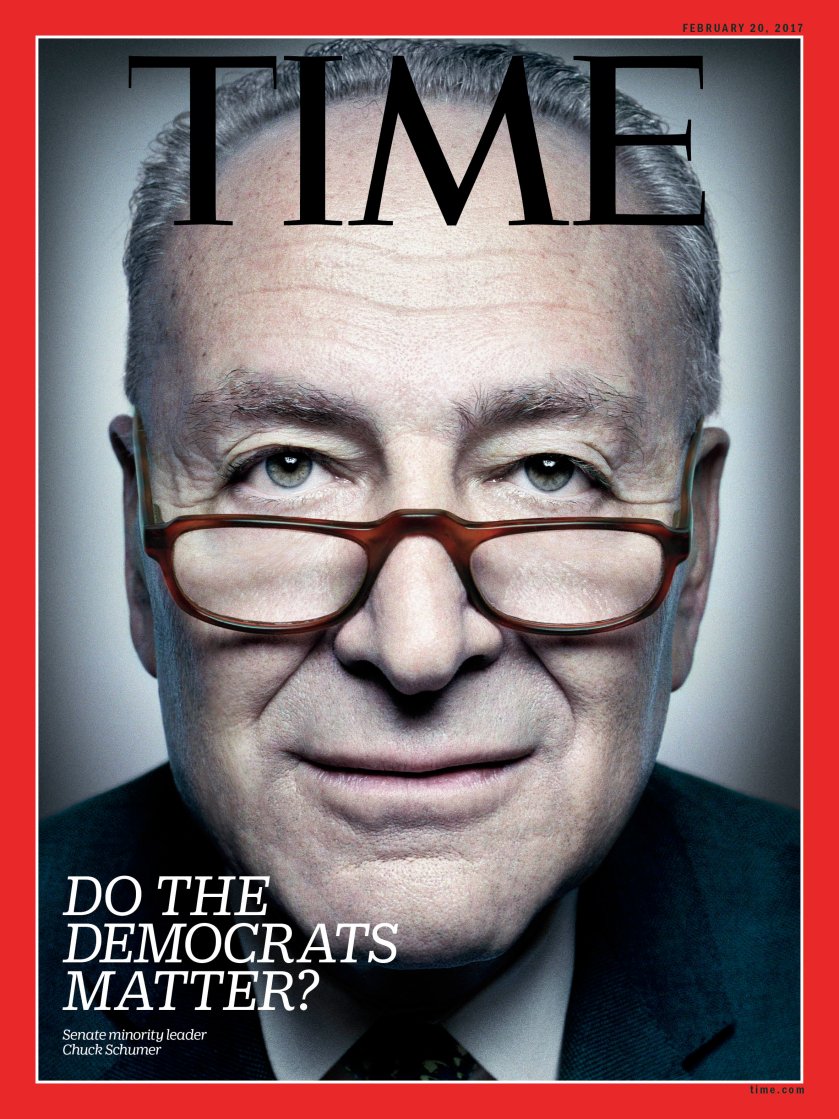

Inside Chuck Schumer's plan to take on President Trump

Put Chuck Schumer and Donald Trump in a room together and you can’t miss the connection. They are the leaders of rival parties, sharp opponents on Twitter and in the press, but they live by the same words, as big and bold as the city that made them. “Beautiful!” they will say, though at different times and about different things. “Wonderful!” “Horrible!” “So, so great!” It is the vernacular of outer-borough kids who, in different ways, scraped their way to the big time. They are two local grandees who boast, yarn, insult and rib each other like they are still on the streets of New York City.

It will take a while–like maybe never–for Mitch McConnell, Paul Ryan or other GOP pooh-bahs to build up a store of Trump war stories to match Schumer’s. In fact the first time congressional leaders visited the new President at the White House, most of his attention focused on their Democratic foil. At one point that evening, Trump recalled a 2008 fundraiser he held for New York’s senior Senator at his Mar-a-Lago club in Florida. The two dozen or so top Democratic donors had cocktails and dinner, serenaded by Peter Cetera, formerly of the rock band Chicago. “I raised $2 million,” Trump boasted.

If you ask Chuck Schumer what it means to be from Brooklyn, he will answer with two words: “No bullsh-t.” Plus he’s a numbers guy. “It was $263,000, to be precise,” he shot back at the President.

For all the chaos and plot twists of the coming weeks, the one sure thing to watch is how these two men go at it, now that Trump presides from the Oval Office and Schumer, 66, is the closest thing the Democrats have to an official opposition leader. Though they know each other and share both experience and instincts, they cannot anticipate each other’s every move. On Trump’s side, unpredictability is a point of pride. And on Schumer’s, even his long résumé and ferocious work ethic could not have prepared him for the choices he faces now. In many respects, both the success of the Trump agenda and the power of the Democratic Party–most immediately, its tenuous hold on 48 Senate seats–depend on how well Schumer plays his cards.

Schumer’s hand at the moment is not strong. Certainly many of the featured items on the President’s agenda–to remake Obamacare, reform the tax code, fund new infrastructure projects and pass new trade deals–will require the help of at least some of the Senators in Schumer’s caucus. But as liberal activists fill the streets with signs calling for resistance, Schumer is under enormous pressure from his left flank to man the barricades and stop Trump, just as the Republicans tried to block anything that came out of Barack Obama’s White House.

There are risks in playing the obstruction game. Stop popular parts of Trump’s agenda for too long and too persistently, and the party’s support can plummet. Play ball with Trump, and Schumer risks a rebellion on his left. Making matters worse is a procedural hair ball as arcane as the Senate itself: getting almost anything significant through the Senate takes 60 votes. Republicans have only 52. If Schumer tries to block Trump’s Supreme Court nominee, Mitch McConnell could trigger the “nuclear option” and change the rules to allow the nominee to pass with only 51 votes. As could any future court nominees, however far outside the mainstream.

In other words, resistance may be inevitable. But it might also be futile. And it may even prove counterproductive to Democrats’ hopes of winning back a majority anytime soon.

Which brings us back to Schumer himself. If he made his reputation as a partisan fighter, his habit and history suggest he would like to negotiate with Trump when and where a deal can be made, which he believes is possible on trade, taxes and infrastructure spending. So with all the pressures on Schumer–from liberals, from centrists and his own instincts–the real question is whether the Senator from Brooklyn is going to fight or compromise and in what order.

On the November night that Trump won, Schumer flew down from New York City into Washington, where he had expected to arrive as the Senate’s majority leader and a key partner for President Hillary Clinton. But then the people spoke, and Schumer’s instinct was to be humble and conciliatory. “Tonight the American people voted for change,” he said as the returns came in, shocking many of the grieving Democrats at the party’s senatorial campaign headquarters.

In the days that followed, Schumer said, he suffered through a sort of depression. He comforted his distraught adult daughters by teaching them the lyrics to the old Shirelles song: “Mama said there’ll be days like this.” Only then did he find relief in a realization. “If Hillary won and I was majority leader, I’d have more fun, and I’d get more good things done, which is why I’m here,” Schumer explains in a Feb. 2 interview in his Senate office, beside a photo of himself with former President Obama in a Brooklyn park. “But with Trump as President and me as minority leader, that job is far more important.”

And harder. The Democratic Party that emerged from the 2016 election is no monolith: liberal firebrands like Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Bernie Sanders of Vermont were preparing for a more militant approach to Trump and some of the Democrats’ donors on Wall Street. Meanwhile, moderates like West Virginia’s Joe Manchin, a former coal executive, and North Dakota’s Heidi Heitkamp traveled to Trump Tower in New York City for meetings that signaled they might bolt the party.

See Pictures of Chuck Schumer Over the Years

Schumer worked the phones to keep both members inside the fold by assuring them they could stake out their own positions when it mattered. “We all think he’s our best friend,” says Manchin. Schumer has since set up regular dinners with five Democrats facing 2018 re-election campaigns in states Trump won, including West Virginia, North Dakota, Indiana, Montana and Missouri. He displays a decidedly unliberal gift from Manchin on his office desk: a donkey and an elephant carved out of coal.

Coming after Harry Reid, who kept more distance from his colleagues, Schumer has worked to strengthen links to other Democrats. During a recent visit to Lake Placid in upstate New York, he stopped by to see fellow New York Senator Kirsten Gillibrand and played chess and read bedtime stories with her young sons. He ceaselessly calls his members to solicit advice. “Chuck is pretty much tethered to his phone,” says Senator Ron Wyden of Oregon. When President Obama went to Capitol Hill on Jan. 4 to urge the Democratic caucus to fight to keep the Affordable Care Act, Manchin called Schumer, telling him he would skip the meeting. Whatever you need to do, Schumer told him.

Then Schumer set about elevating members on his liberal flank. One of Schumer’s first official acts was to promote Sanders and Manchin to leadership, elevate Warren and add Michigan Senator Debbie Stabenow. That helped mollify the troops. “I don’t know how much more thoroughly you can cover the waterfront,” says Senator Claire McCaskill of Missouri. (Actually you can: Schumer, who uses a flip phone, has memorized the 47 cell-phone numbers of his caucus. “I like numbers,” he says.)

In December he held a closed meeting with a group of top-ranking Democrats to figure out how to delay Trump’s efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act. The newly promoted Sanders spoke up. “If we are really going to make a difference, we have to do this outside the Beltway,” Sanders told Schumer, according to a Sanders aide. Schumer helped Sanders organize rallies across the country protesting the repeal of Obama’s signature law. Then Schumer orchestrated an unprecedented holdup of a President’s Cabinet nominations, sending his caucus members to grill them in committee hearings and stalling the votes to confirm them on the Senate floor.

But even as that strategy took shape, an organic rebellion burst into the streets, first with the massive women’s march and then with protests against Trump’s refugee ban at the nation’s airports. It was just a matter of time before the liberal anger turned on Schumer himself, for not doing more to stop the Trump agenda. At a candlelight vigil Schumer organized outside the Supreme Court on Jan. 30 to protest the ban, the crowd turned on Schumer, chanting, “Do your job! Do your job!” “The Democratic leadership is not listening to their base,” said Claudia Gross-Shader, an employee of the city of Seattle, at the vigil. The next day, protesters massed outside Schumer’s Brooklyn apartment. “Grow a spine!” some chanted. Others chanted worse.

So Schumer is trying to juggle, saying he is willing to work with Trump on some issues–but will draw the line where the new President’s proposals conflict with Democratic “values.” “If he says, ‘I want to get rid of the carried-interest loophole,’ which he campaigned on, we’ll support it,” Schumer says. “If he has a real plan to deal with the high cost of prescription drugs,” he continues, “we’ll work with him.”

For Charles Ellis Schumer, the middle of the road is familiar ground. Born to an exterminator and a homemaker in a middle-class neighborhood in Brooklyn, Schumer attended the same high school as Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Bernie Sanders. A side job working the mimeograph machine for Stanley Kaplan’s new test-prep company as a teenager helped him ace the SAT, setting him on a path to Harvard College and Harvard Law during the late 1960s.

His introduction to politics came in 1968, when he worked for Eugene McCarthy in New Hampshire. Even in those years, Schumer was a cautious breed of progressive, skeptical of more-extreme activists on the left, including some from wealthier backgrounds, who sometimes advocated violence. He remembers watching them at protests try and provoke police officers by calling them pigs. “I would say to these kids, ‘I grew up with these police officers,’” Schumer recalls. “‘Don’t take their humanity away.’”

In 1974 he ran for and won a seat in the New York State assembly at the age of 23, representing his parents’ Brooklyn district. He spent five years in Albany before running for Congress, winning in 1980. During his 18 years in the House, he earned a reputation as a sharp-elbowed partisan. He helped guide the 1993 Brady gun-control bill and a controversial 1994 crime bill through Congress and became known as a tough dealmaker. It would pay off: he overcame several other Democrats for the right to challenge Al D’Amato for his Senate seat in 1998, eventually beating the sharp-tongued Long Island incumbent by a double-digit margin.

Schumer’s early years in the Senate were not easy. No sooner had he arrived in the upper chamber than he found himself overshadowed by New York’s junior Senator, Hillary Clinton, who was elected in 2000. The popular former First Lady stole the spotlight wherever the two went, both in their state and elsewhere, even at a favorite Chinese restaurant he took her to on Capitol Hill. But together they helped persuade President George W. Bush to deliver $20 billion to New York after the 9/11 attacks. (Schumer grew to respect Clinton, who he privately would say had learned to “climb the greasy pole” of politics–something Schumer believes he did himself–and which he thinks distinguishes him and his record from Barack Obama, who was a superstar from the beginning.)

By then, of course, Schumer had repeatedly crossed paths with the Trump clan. His maternal grandfather had been a builder in Brooklyn with Trump’s father Fred Trump. As a young man, Schumer remembers seeing Fred tooling around town in his black Cadillac with the license plate “FT.” More often than not, the younger Trump and Schumer found themselves on opposing sides: in 2000, Trump tried to build a casino in Manhattan; Schumer wrote a letter to the Bureau of Indian Affairs to block him. “Casinos do not belong in Manhattan,” Schumer argued. Years later, Schumer fought Trump again when the real estate mogul and a group of investors wanted to sell an affordable-housing development in Brooklyn at a profit, a move that would have imperiled the rent rates of the low-income tenants. Schumer won the fight.

Despite their spats, Trump was a regular donor–he saw it as the cost of doing business in Manhattan. In total, the Trump family has given more than $80,000 to Schumer’s electoral efforts over the years, according to federal records, which is not a huge amount by political standards, but not token either. (The $263,000 Trump brought in at Mar-a-Lago was raised with other donors.) “He never had hard feelings,” Schumer says of Trump. “It was like business for him.” In 2006, Schumer returned the favor and appeared on Trump’s The Apprentice, hosting contestants for a breakfast at a posh Washington hotel. “Even when he was much younger, you knew he was going to go places,” Schumer told the Apprentice contestants.

Schumer can be aggressive in public but is looser in private. He has strong relations with such Republicans as Senators John McCain, Lindsey Graham and Lamar Alexander, who regard him as a partner they can work with. “He’s a tough negotiator, but his word is good,” says McCain. In his first one-on-one meeting with Representative Paul Ryan of Wisconsin over immigration reform in 2013, they talked for 20 minutes about ice fishing and Asian carp, an invasive species that has threatened to overrun lakes in both their states. He is regarded as perhaps the hardest-working Senator by his peers and is more trusted by Republicans than Reid was. “Even if he’s out to kill you, you know he’s going to keep trying to kill you,” says a top Republican Senate aide. “It’s more predictable, which makes the place run better.”

If there is any reason to be optimistic about the level of partisanship in Washington, it might be that Schumer and Trump don’t think so differently, at least on some issues. “I’m closer to Trump’s views on trade than I am to Obama’s or Bush’s,” says Schumer, who opposed both NAFTA and the Trans-Pacific Partnership. China, he adds, is a particularly bad actor on trade matters, and Schumer has called on Trump to name China a “currency manipulator” and work harder to guard against theft of intellectual property. Schumer says he was “sort of glad” when Trump caused a mini-diplomatic crisis by accepting a phone call from Taiwan’s President, angering Beijing. “With other nations, free trade may hurt us, but China is rapacious.” Adds Schumer: “I love America. I want America to be No. 1.”

It’s worth remembering, too, that Schumer and Trump were both shaped by the same unforgiving New York media climate. They are both obsessive consumers of news and have a finely tuned instinct for what pops with working-class New York City subway riders. If Trump is obsessed with ratings, Schumer is obsessed with headlines: he regularly reads the New York papers, the national papers and the smaller papers around the country. Like Trump, Schumer is a master at celebrating himself in the press, whether it’s helping to keep the Buffalo Bills in New York State; fighting to lower the price of flights from Rochester, N.Y., to Disney World; or keeping jobs in upstate New York. “He is somebody that tactically understands what Trump has succeeded in doing so far,” says Brian Fallon, a former Schumer aide.

Schumer arranged several telephone calls with Trump late last year in the hopes of steering Trump toward a less combative path. In those private conversations, Schumer says, he warned Trump about the rightward tilt of his Vice President Mike Pence and the most conservative flank of the Republican Party. “You ran as a populist,” Schumer remembers saying on the phone, “but if you let the hard right take you over, you will not succeed as President.” At one point, Schumer says, he told the President that the only infrastructure bill that would really work would need to cost at least $1 trillion, funded by direct government spending (as opposed to tax credits), with labor and environmental protections and no accompanying cuts to entitlements. Schumer says Trump responded with two encouraging words: “I know.” (The White House declined to comment on the calls.)

On the other hand, Trump has not hesitated to blast Schumer for being a drama queen, mocking his tearful denunciation of Trump’s “mean-spirited and un-American” refugee policy. “I noticed Chuck Schumer yesterday with fake tears,” Trump said. “I’m going to ask him who is his acting coach.” Schumer, an easy crier whose middle name honors Ellis Island and whose daughter is named for Emma Lazarus, got a kick out of Trump’s jab.

What follows now is a complex series of calculations for Schumer. He will try to block Republicans from repealing the Affordable Care Act root and branch, but may blink when some of his members want to help Republicans on a replacement. It seems increasingly likely he will try to bring down Neil Gorsuch, Trump’s conservative Supreme Court pick, but it seems just as likely that he will be unable to then prevent McConnell from changing the Senate rules to force Gorsuch through with 51 votes. Schumer’s antics have angered the White House. The country is getting “frustrated,” said a White House official, “with Senator Schumer’s tactics to obstruct the will of the American people.”

Shortly after Barack Obama won the White House, McConnell gave a speech announcing that the top priority for Republicans would be to make Obama a one-term President. Schumer’s offer to Trump is more nuanced. Govern from the middle, Schumer is suggesting, and I will share some votes. Govern from the right, and you’ll give Democrats a chance to reclaim the populist mantle in coming elections. “We’re not going to do what the Republicans did and oppose it just because the name Trump is on it,” Schumer said.

Still, for all the phone conversations, the warnings and the remonstrations between the two New York potentates, Schumer sees the shock and awe of Trump’s first weeks in office as a bad sign. He is waiting for Trump to move to the middle but is increasingly skeptical that the President will ever get there. “You never know if he’s really paying attention,” says Schumer of Trump. It could have been “wonderful,” “beautiful” and “great.” But the rules have changed, and a long fight seems unavoidable. They are in Washington now.

–With reporting by ZEKE J. MILLER/WASHINGTON